|

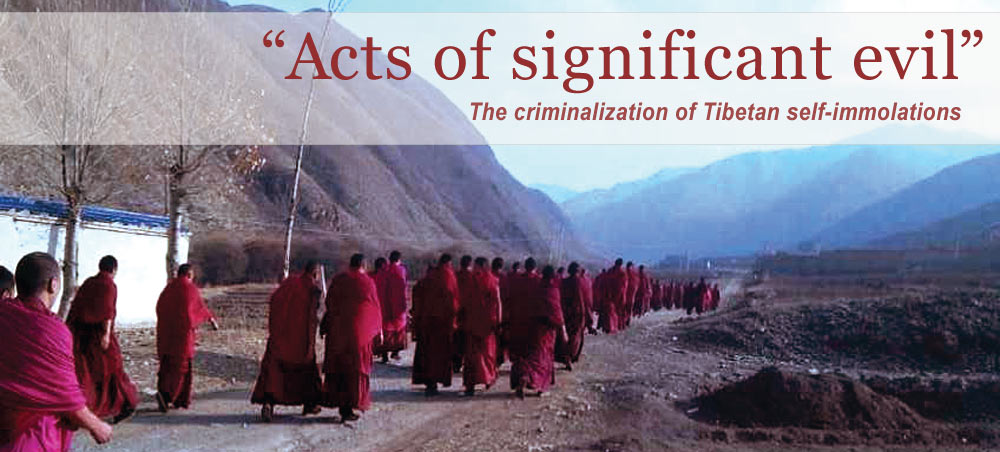

A Special Report by the International Campaign for Tibet |

- Criminalizing self-immolations

- The Opinion

- Collective punishments

- Questionable legal basis

- Counter-responses by Tibetans

- Recommendations

Executive Summary

Since 2009 there have been 131 self-immolations of Tibetans in Tibet and China whose common call has been for the return of the Dalai Lama and for freedom in Tibet. The Chinese Communist Party has responded with an intensified wave of repression in Tibet, by punishing those allegedly “associated” with self-immolators, including friends, families and even entire communities.

- According to guidelines announced in the state media by the end of 2012, Tibetans can be sentenced on homicide charges based on their alleged ‘intent’ and presumed ability to influence a Tibetan who has self-immolated.

- As a consequence, since 2012, at least 11 Tibetans have been sentenced to prison terms or even to death on “intentional homicide” charges, because they allegedly have “aided” or “incited” others to self-immolate. There is no indication about a formal legislative process having been observed by the Chinese authorities justifying the application of such a provision. However, such process is mandatory according to the Chinese constitution when introducing new criminal offenses.

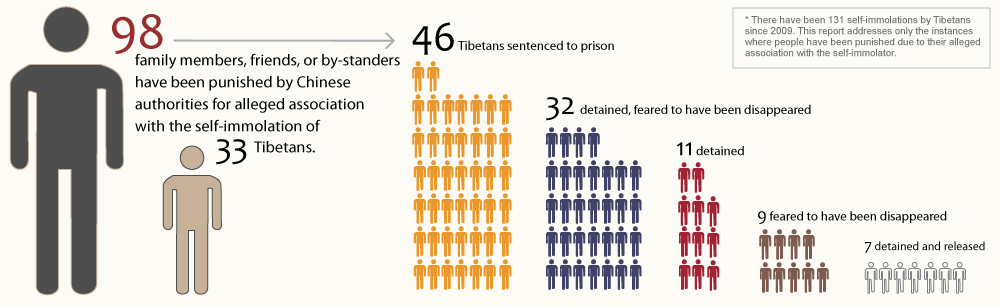

- This approach has been complemented by a considerable number of other sentences, detentions and disappearances of Tibetans. This report lists 98 Tibetans who since 2010 have been subjected to such measures because of their alleged association to a self-immolation. The number of detentions may be higher, as Chinese media has reported that there were nearly 90 arrests linked to self-immolations in Qinghai and Gansu provinces alone.

- In a number of cases documented in this report, there is no evidence that those convicted either spoke to the self-immolator beforehand or even knew the self-immolator. Often, there is no further detail available on the underlying legal background. However, it is notable that the guidelines passed in 2012, while – apart from “intentional homicide” – stipulating further punishable behavior, may have provided yet another framework for persecution. Given the systematic disregard for principles of due process in the People’s Republic of China, it must be assumed that affected Tibetans did not enjoy their right to a fair trial. In fact, in a number of cases documented in this report, there is reason for concern that those convicted did not receive a fair trial, as prescribed by international law.

- Furthermore, the Chinese authorities have also stepped up deliberate attempts to penalize families and the broader community when a Tibetan self-immolates. In a set of new regulations passed in April 2013 in one of the areas where several self-immolations have occurred, the entire community is faced with financial and other penalties.

The International Campaign for Tibet (ICT) is deeply concerned about the apparent contravention of these new measures to both national and international law and criticizes the apparently new quality of repression in Tibet inherent to the authorities’ approach.

- ICT calls for the release of those imprisoned for being associated to self-immolators, e.g. for allegedly “aiding” or “inciting” them. ICT is also highly concerned about the cases of “disappearances” connected to self-immolations and calls for a full disclosure of the whereabouts of the individuals concerned. Moreover, the Chinese authorities must abolish all measures of collective punishment for families and entire communities.

- ICT calls on the international community to raise with Chinese officials the inconsistency of the measures with international and Chinese law.

- The approval of new guidelines, involving three of the highest institutions in the Chinese political system, and their implementation, appear to reflect a political imperative of the new leadership under President Xi Jinping to continue hard lines policies in Tibet that rely on deterrence and repression. ICT is calling upon the Chinese government to instead address the underlying grievances of Tibetans by respecting their universal rights and by entering into meaningful negotiations with the Tibetans.

Note on Methodology

This report presents 23 cases involving 98 individuals persecuted for alleged association with 33 self-immolations by Tibetans, covering a period from February 2009 to February 2014. It is not intended to provide a comprehensive or exhausting list of all people who have been arrested, detained, disappeared or sentenced due to this alleged self-immolation. Given the tight controls on information flow by Chinese authorities and the dangers faced by Tibetans in passing along information to the outside world, such a comprehensive accounting is not possible. The cases listed in the report come from information published by Chinese state media, independent media outlets, and from information gathered by ICT from sources inside and outside Tibet.[1]

» Findings

Since 2012, at least 11 Tibetans have been sentenced to prison terms or even to death on “intentional homicide” charges, because they allegedly have “aided” or “incited” others to self-immolate.

• •

This report lists 98 Tibetans who since 2010 have been subjected to punishments because of their alleged association to a self-immolation.

• •

In a number of cases documented in this report, there is no evidence that those convicted either spoke to the self-immolator beforehand or even knew the self-immolator.

• •

Chinese authorities have stepped up deliberate attempts to penalize families and the broader community when a Tibetan self-immolates.

» Recommendations

ICT calls for the release of those imprisoned for being associated to self-immolators, e.g. for allegedly “aiding” or “inciting” them.

• •

ICT calls on the international community to raise with Chinese officials the inconsistency of the measures with international and Chinese law.

• •

ICT calls upon the Chinese government to address the underlying grievances of Tibetans by respecting their universal rights and by entering into meaningful negotiations with the Tibetans.

Troops are seen closing in on Dorje Rinchen’s body after he has self-immolated. Laypeople and monks appear to be trying to protect him from being taken away by troops. Six people were sentenced in association with Dorje Rinchen’s self-immolation. It is not known if they were among those in the crowd trying to prevent him from being taken by troops.

1. Context: The drive against Tibetan self-immolations and “stability maintenance”

In Tibet, there has been a dramatic intensification of state control, which has taken the form of a violent crackdown since protests swept across the plateau in 2008. Since the self-immolations began, the authorities have gone so far as to characterize their approach in Tibetan areas as a “war against secessionist sabotage.”[2] Jia Qinglin, former chairman of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) and a key figure in Tibet policy, outlined the hardline policies in the buildup to the Party Congress in Beijing in 2012 when he said that: “The country is in a key period of fighting against the Dalai Lama group.”[3]

Instead of addressing the grievances of Tibetans as indicated, for example, in the countrywide protests in 2008 and in ongoing protests against, for example, discriminatory educational policies, environmental destruction, restriction on religion, or loss of cultural identity, the Party has deliberately chosen to react to dissent expressed by Tibetans with repression and a politicization of criminal law.

According to the Party’s narrative, it is outside forces, the Dalai Lama and his “clique,” “conducting separatist activities for a long time to sabotage the development and stability of Tibet,” while “at present, Tibet presents a picture mixing traditional and modern elements, featuring economic and political progress, cultural prosperity, social harmony, sound ecosystem and a happy and healthy life for the local people.”[4]

As a result, and in order to remain in coherence with its interpretation of the state of affairs in Tibet, the Party has chosen to employ a “stability maintenance”[5] approach which includes a systematic attempt to block news of the arrests, torture, disappearances and killings that have taken place across Tibet.

Furthermore, the Party pursues the strategy of actively establishing its presence in all layers of Tibetan society; for example, Chinese government or Communist Party officials are being stationed in monasteries permanently.[6] This has led to a more pervasive and systematic approach to “patriotic education” and a dramatic increase in work teams and Party cadres, for example, in rural areas of the TAR.

Consequently, the Party portrays Tibetan self-immolations as a result of outside interference by the Dalai Lama, and not as an expression of legitimate grievances of those who self-immolate. Likewise, Beijing may see them as a threat to the legitimacy of China’s rule, as they challenge the claim of the Central State that there is a “happy and healthy life for the local people.”

The response of the Party state is twofold: firstly, it creates a narrative that those who self-immolate have been incited by others, necessarily outside forces or by those accused of instigating them. Secondly, it creates a repressive environment to deter individuals from self-immolating, by means of threatening to allocate punishment to communities, families and friends. While doing so, the authorities ignore and violate international human rights law, and even its own law, and thus abuse its power in the name of “maintaining stability.” The drive to criminalize self-immolations is indicative of such an abuse of power.

2. Charges of “inciting to self-immolation” and “intentional homicide” discriminatorily applied to Tibetans but not Chinese

In the recent past there have been a number of self-immolation incidents occurring in Chinese areas of the People’s Republic of China (not in Tibetan areas). In a series of self-immolations in reaction to forced evictions, at least 41 people of mostly Chinese ethnic origin have self-immolated in the PRC between 2009 and 2011.[7]

In reaction to these self-immolations, the Chinese government has applied a variety of policies. In its 2012 report “Standing their ground,” Amnesty International documents 28 cases of self-immolations involving 41 individuals as a result of forced evictions in China. In most of these 28 cases, the report details that the authorities have not reacted to the self-immolations, neither by seeking redress of the situation nor by persecuting family or friends of the self-immolator. To the contrary, in at least seven of these cases, the authorities have sacked or investigated officials for their alleged wrongdoings against those who had been violently evicted. The report does not document any cases of legal persecution of the immediate environment of the self-immolator. In fact, in none of the cases, the authorities have applied the concept of “inciting to self-immolate” to anyone in the immediate environment of the self-immolator. There is no report about any investigations conducted by the authorities to that extent in these cases, let alone about charges for having committed “intentional homicide.”

With regard to self-immolations by Tibetans, a clearly different approach by the authorities is notable. In August 2011, two Tibetans were sentenced for “intentional homicide” and received sentences of 10 and 13 years imprisonment. In this case the concept of incitement to self-immolation and the resulting sentence of “intentional homicide” were apparently applied for the first time to Tibetans.[8] According to Chinese state media’s report on the case, the two Tibetans sentenced had “plotted, instigated and assisted in the self-immolation of fellow monk Rigzin Phuntsog, causing his death.”[9]

Furthermore, by the end of 2012, the Chinese authorities acted to impose new punishment regimes in response to the self-immolations in Tibet. While the wave of self-immolations in Tibet had begun already in 2009, there was a notable peak of self-immolations toward the end of 2012 that coincided with the Communist Party 18th National Congress in Beijing in November 2012. According to the new guidelines, “anyone who organizes, plots, incites, coerces, entices, abets, or assists others to commit self-immolations shall be held criminally liable for intentional homicide in accordance with the Criminal Law.”[10]

Significantly, the authorities had treated such alleged “plots” differently in the past. In 2001, according to the state media, the authorities had detained Tibetan “spies” and “crushed a plot” to incite other Tibetans to self-immolate.[11] Instead of being charged with “intentional homicide,” the concerned individuals were convicted on charges such as “agitating separatism and espionage.”

3. Portraying self-immolations in the state media

Particularly in the English language state media, the authorities have portrayed Tibetans who set fire to themselves since the self-immolations began in 2009 as psychologically unstable, criminals, or copycats, having fallen prey to outside manipulation.[12] However, the response by Tibetans remained one of respect and compassion, as for example reflected in prayer ceremonies held for a deceased self-immolator or condolences offered to families.

But the further response, as apparent by the end of 2012, by the Party authorities portrays the self-immolator as being motivated “to split the nation and […] endanger public safety and social order, classifying their self-immolations as illegal criminal acts,”[13] and signals that any involvement with someone who self-immolates – including simply witnessing it – can lead to a charge of ‘intentional homicide,’ with the authorities constructing a justification for severe penalties imposed such as long prison sentences and even the death penalty.

The state media has not announced severe penalties for Tibetans who survived self-immolation, perhaps due to concern that this might arouse further sympathy and thus be counter-productive. Instead those who survive self-immolation are ‘disappeared,’ and often their family and friends do not know where they are.[14] Some of those who have survived have been used by state media for propaganda purposes, although they have not always adhered strictly to the Party line.[15]

CASE STUDY 1: Sentenced to death for “intentional homicide” – the case of Lobsang Kunchok

Lobsang Kunchok

The first self-immolation in Tibet was carried out by a Kirti monk, Tapey, in Ngaba, and Kirti monks dominated in the total of self-immolations in the first two years; current or former Kirti monks made up 12 of the first 23 self-immolations (February 27, 2009, to February 19, 2012). As the frequency of self-immolations has increased and spread geographically across Tibet, the prevalence of Kirti Monastery monks among self-immolators decreased, and laypeople in different areas of Tibet have dominated the total. Further information about the specific self-immolations that Lobsang Kunchok and Lobsang Tsering were accused of inciting is not available.

Tibetan monk Lobsang Kunchok was given a death sentence suspended for two years (which is normally converted to life), and his nephew Lobsang Tsering was sentenced to ten years.

They were the first cases of Tibetans to be prosecuted for ‘intentional homicide’ in connection with self-immolations following the publication of the ‘opinion’* in the Gansu newspaper in December 2012. The trials were accompanied by elaborate propaganda efforts, with news of the alleged conspiracy was covered in the official press and state television. Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Hong Lei told journalists: “We hope through the sentencing of these cases, the international community will be able to clearly see the evil and malicious methods used by the Dalai clique in the self-immolations and condemn their crimes.”[16]

State media coverage did not indicate any evidence for the charge of “intentional homicide.” The verdict caused great distress among Tibetans in the area. At the time of their sentencing, a Tibetan in exile who is from the region and had spoken to local Tibetans told ICT: “Lobsang Kunchok and his nephew are good men and respected in their local communities, and they are likely to have responded to requests to help families who were suffering. This sentencing to death can only make the situation worse and risk further self-immolations happening in Ngaba.”

The priorities of the authorities in seeking to suppress information reaching the outside world, and other areas of Tibet, are evident in the further charges imposed on Lobsang Kunchok for sending out information regarding self-immolations, which it said was “used by some overseas media as a basis for creating secessionist propaganda.” The police had initially accused both Lobsang Kunchok and Lobsang Tsering of carrying out the instructions of the Dalai Lama and his followers, according to Tibetans in exile.

The sentences were handed down by the Intermediate People’s Court of Ngaba prefecture. On January 28, Xinhua had acknowledged that the two Tibetans were not represented by their own lawyers. Despite an assertion by a judge who told the Global Times that: “authorities obtained sufficient evidence showing it [the alleged crimes] had been instructed by ‘forces from abroad’,” no evidence was presented to justify the sentencing.

According to the Congressional-Executive Commission on China, “According to PRC law, the trials of the monks on charges of ‘intentional homicide’ should not have been heard before a county-level court—instead, the trial should have been heard before the Aba T&QAP Intermediate People’s Court. Article 20(2) of the Criminal Procedure Law states, ‘The Intermediate People’s Courts shall have jurisdiction as courts of first instance over […]ordinary criminal cases punishable by life imprisonment or the death penalty.’ Article 232 of the Criminal Law states, ‘Whoever intentionally commits homicide shall be sentenced to death, life imprisonment or fixed-term imprisonment of not less than 10 years; if the circumstances are relatively minor, he shall be sentenced to fixed-term imprisonment of not less than 3 years but not more than 10 years.’ Official media reports have provided no information on why trials on charges punishable by the death penalty or life imprisonment were heard before a county-level court. An additional unusual aspect of the trials is that the county court that reportedly tried the cases was not the county court with jurisdiction over the site where the alleged crimes were committed: Kirti Monastery is in Ngaba, not Barkham, county. The Barkham County People’s Court is located in the prefectural capital, along with the Ngaba T&QAP Intermediate People’s Court.”[17]

In a response to a question from the press on August 29, 2011, a U.S. State Department spokesperson said the government was “concerned” by the conviction for “intentional homicide.” The spokesperson also said: “We urge the Chinese government to ensure transparency and to uphold the procedural protections and rights to which Chinese citizens are entitled under China’s Constitution and laws and under international standards.”

CASE STUDY 2: Detained for holding prayer services: the cases of monks Tsundue and Gedun Tsultrim

Two monks, Tsundue and Gedun Tsultrim, were sentenced to three years each in prison after they held prayers for a Tibetan, Wangchen Norbu, who set fire to himself and died. Tsundue, who is in his late twenties, and 30-year old Gedun Tsultrim, were detained on November 21, 2012, as they were on their way to pay their respects and say prayers at the home of Wangchen Norbu. Other monks and laypeople were also blocked from going to Wangchen Norbu’s house, and some of them prayed by the road where they were stopped by police and officials.

It was the first known case of monks being sentenced for praying, or attempting to pray, for a Tibetan who has self-immolated. It is possible that the monks took responsibility for organizing the prayers in order to protect the broader community.

Both lay people and monks who had been attempting to walk to Wangchen Norbu’s home to carry out traditional prayers were subject to harassment and intimidation afterwards. The sentencing of Tsundue and Gedun Tsultrim is likely to have been intended to send a warning to others. According to one Tibetan who spoke to sources, it also appears to indicate that they took responsibility for organizing the prayers in order to protect others.

According to the same exile Tibetan sources, Tsundue, in his late twenties, was accused of being the organizer of a prayer ceremony following the self-immolation at his monastery, Bido in the neighboring township to Kangtsa in Xunhua (Do-wi) Salar Autonomous County in Tsoshar (Chinese: Haidong) prefecture, Qinghai. He was also accused of being one of the main monks intending to lead the traditional prayers at Wangchen Norbu’s home two days after he self-immolated. Gedun Tsultrim, who was a chant-master in charge of prayers at a monk at Bido monastery in Bido township, was accused of collecting offerings made by monks for Wangchen Norbu’s family, and for organizing monks to go to his family home for prayers.

Monks and local people sought their release but failed to convince the local authorities, and the monks’ families did not receive any documentation clarifying the sentences. The two monks are believed to be held in Xining and it is not known if families have been given permission to visit them.

Eventually, the authority announced that Gendun Tseltrim was sentenced to three years imprisonment. Since then, the two monks were transferred to a prison in Xining and the authorities have not given permission to the families and relatives to visit them.

Wangchen Norbu, in his mid-twenties, had died after self-immolating two days earlier near Kangtsa Gaden Choepheling monastery in Kangtsa in Xunhua County in Tsoshar prefecture, Qinghai province.

Sources in the region say that Wangchen Norbu set himself ablaze and shouted slogans calling for the return of the Dalai Lama to Tibet, release of the Panchen Lama and freedom for Tibet. Kangtsa is adjacent to the hometown of the late 10th Panchen Lama in Xunhua county, Tsoshar prefecture, Qinghai province (the Tibetan region of Amdo).

CASE STUDY 3: Death penalty after unfair trial – the case of Dolma Kyab

Dolma Kyab (Photo: Phayul.com)

Dolma Kyab (Chinese transliteration: Drolma Gya), was sentenced to death by the Intermediate People’s Court in Ngaba (Chinese: Aba) for “killing his wife and burning her body to make it look as if she had self-immolated” according to the Chinese state media on August 16, 2013.

The imposition of the death penalty is rare in Tibet and there are concerns that the verdict may have been influenced by political circumstances. Dolma Kyab is being held in prison in Barkham (Chinese: Maerkang), the capital of Ngaba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture in Sichuan (the Tibetan area of Amdo). According to Tibetan sources in exile, he has been severely tortured.

A death penalty case must be reviewed by a higher court according to Chinese law. If a first trial by an intermediate people’s court hands down the death penalty, the first appeal is conducted by a High People’s Court’ and also by the Supreme People’s Court. The higher courts have the power to change the verdict, including the imposition of a death sentence suspended for two years, which generally means life imprisonment. If the death penalty is upheld without reprieve, the execution is generally carried out shortly afterwards. The current status of Dolma Kyab’s case is not known.

Tibetan sources report that Dolma Kyab was tortured prior to his trial, and that he has declared his innocence. His current welfare is not known. According to the same sources, it appears that Dolma Kyab did not receive a fair trial and due process, without effective legal counsel of his own choosing. The state media report on his sentencing makes no mention of any evidence in this case other than a ‘confession,’ and it is known that torture is frequently used to extract confessions in China.

The circumstances of the case are still unclear due to the oppressive political environment and climate of fear in the area. According to some Tibetan sources, which could not be fully confirmed, Kunchok Wangmo set fire to herself late at night in March, 2013, and died. The authorities in Ngaba appear to have sought to build a case against Dolma Kyab, accusing him of killing his wife. Various Tibetan sources reported that on the morning after Kunchok Wangmo’s death, security officials came to the family home and offered substantial bribes for Dolma Kyab to say that she had committed suicide due to family problems. The same sources say that his arrest followed his refusal to do so, although full details of the circumstances are not known.

Hover over picture of self-immolator(s) to see names of Tibetans punished for alleged association.

SENTENCED

Jamyang Phuntsog, six years

SENTENCED

Lobsang Tsundue (Drongdru), 11 years

Lobsang Dargye, three years

Lobsang Tenzin (aka Nak Ten), 10 years

Lobsang Tenzin, 13 years

Lobsang Kunchok, Death penalty, suspended for two years

Lobsang Tsering, 10 years

DETENTION

Rinchen Dargye, September 10

SENTENCED

Khedrup Gyatso, 10 years

Sangay Gaytso, nine years

Kalsang Gyatso, eight years

Kunchok Gyatso, one year, nine months

Sherab Gyatso, one year six months

Jamyang Woeser, three years

Damcho Tsultrim, two years

Kalsang Dakpa, one year

Dorje, two years

Damcho, two years

DETENTIONS

Lobsang Sangay, August 28 or 29, 2012

Jamyang Chenko, August 28 or 29, 2012

Lobsang Palden, August 28 or 29, 2012

DETENTIONS

Tsewang Jermey, October 4, 2012

Lubum, October 5, 2012

Kalsang Gyaltsen, October 5, 2012

DETENTIONS

Tashi Gyatso, November 12, 2012

Jigme Gyatso, December 2012

Kalsang Gyatso, December 2012

Kunchok Gyatso, December 2012

DETENTIONS

Geden Jamyang, disappeared

Dorkho Kyab, disappeared

Choepal Dorjee, disappeared

Choezin, disappeared

Lobsang Choepal, disappeared

SENTENCED

Pema Dhondup, 12 years

Kalsang Gyatso, 11 years

Pema Tso, eight years

Lhamo Dhondup, seven years

Dolkar Gyal, seven years

Yangmo Kyi, three years

DETENTION

Phagpa Kyab, whereabouts unknown

SENTENCED

Aku Gyatak, four years

Dorje, two years, six months

Lhamo, two years

Tsundue Choeden two years

Kunchok Sonam, sentenced to unknown term

Unidentified male, two years

Phagpa, 13 years

DETENTIONS

Kalsang Sonam, detained in November 2012

Soebum, detained in November 2012

Dakpa Gyatso, detained and released

Jigme Tenzin, detained and released

Dolma Kyab, detained

SENTENCED

Jamyang Tseten, four years

SENTENCED

Tsundue, three years

Gedun Tsultrim, three years

DETENTIONS

Rigshel, whereabouts unknown to ICT

Chakthar, whereabouts unknown to ICT

Shawo, whereabouts unknown to ICT

Tsundue, whereabouts unknown to ICT

Chodon, whereabouts unknown to ICT

SENTENCED

Lhamo Dorje, 15 years

Kelsang Sonam, 11 years

Kalsang Tsezung Kyab (or Kalsang Kyab), 10 years

DISAPPEARANCES

Kalsang Samdup • Kalsang Namden

Nyima • Dorje Dhondup

Sonam Kyi

SENTENCED

Gendun Gyatso, six years

DISAPPEARANCES

Lobsang Pakpa

Jamyang Soepa

Jamyang Lodoe

Jamyang Gyatso

SENTENCED

Dotruk, ten years, May 2013

Ugyen, one year, nine months

Chokyab, one year, six months

SENTENCED & RELEASED

Tamding Tsering, approximately 1.5 years (released July 29, 2013)

SENTENCED

Gergon, four years

Norbu Dorje, four years

Sonam Yaphel, five years

SENTENCED

Jigme Thamkey, five years

Kalsang Dhondup, six years

Lobsang, four years

DETENTIONS

Tenzin Gyatso, detained July 20

Palden Gyatso, detained July 21

Sangay Palden, detained July 21

Palden Yignyin, detained July 24

Rabsel, detained July 27

Ludup Soepa, detained July 27

Yunten Gyatso, detained July 31

DETENTIONS

Gelak, detained January 18, 2014

Tselha Kyab, detained January 18, 2014

Tsekyab, detained January 18, 2014

DETENTIONS

Gyatso, detained February 2014, released

Paldor, detained February 2014, released

Paldor’s wife (Unknown), released

Pema (if not Paldor’s wife), released

Tseten Gyal, may still be in detention

[mgl_gmap mapid=”prisonerreport” lat=”34.589164″ long=”102.485315″ zoom=”6″ width=”100%” height=”380px” skin=”retro” controls=”pan,zoom,scale,overviewMap,scrollWheel” ][mgl_marker lat=”32.903264″ long=”101.708032″ icon=”https://savetibet.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/01-02-05-marker.png”]1. One sentenced following the self-immolation of the monk Tapey in Ngaba (February 2009)

2a. Four sentenced after the self-immolation of Phuntsog in Ngaba (March 2011)

2b. Two sentenced (one to death) following the self-immolation of Phuntsog in Ngaba (March 2011)

5. Three detained and fear for disappearance after the self-immolations of Lobsang Kalsang, Lobsang Damchoe in Ngaba (August 2012)

Ngaba town, Ngaba prefecture[/mgl_marker][mgl_marker lat=”30.982945″ long=”101.120264″ icon=”https://savetibet.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/03-marker.png”]3. Detentions and fear for disappearance, one named, following self-immolation of Tsewang Norbu in Kardze (August 2011)

Tawu, Kardze prefecture[/mgl_marker][mgl_marker lat=”37.298671″ long=”99.028742″ icon=”https://savetibet.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/04-marker.png”]4. Ten sentenced following the self-immolation of Damchoe Sangpo in Tsonub (February 2012)

Themchen, Tsonub prefecture[/mgl_marker]

[mgl_marker lat=”31.480832″ long=”93.679773″ icon=”https://savetibet.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/06-marker.png”]6. At least three detained and fear for disappearance after self-immolation of Gudrub in Nagchu (October 2012)

Driru, Nagchu prefecture[/mgl_marker]

[mgl_marker lat=”36.093535″ long=”102.260095″ icon=”https://savetibet.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/20-marker.png”]20. Three sentenced following self-immolation of Phagmo Dundrup in Tsoshar (February 2013)

Bayan, Tsoshar[/mgl_marker]

[mgl_marker lat=”35.846796″ long=”102.483942″ icon=”https://savetibet.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/13-marker.png”]13. Two sentenced following the self-immolation of Wangchen Norbu in Tsoshar (November 2012)

Kangtsa, Tsoshar[/mgl_marker]

[mgl_marker lat=”35.519409″ long=”102.028696″ icon=”https://savetibet.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/11-marker.png”]11. Seven sentenced, five detained (at least two released) following nine self-immolations in Malho (November 2012)

Rebkong, Malho prefecture[/mgl_marker]

[mgl_marker lat=”35.196853″ long=”102.521021″ icon=”https://savetibet.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/09-marker.png”]9. Six sentenced following the self-immolation of Dorje Rinchen in Sangchu (October 2012)

Labrang, Sangchu county, Kanlho prefecture[/mgl_marker]

[mgl_marker lat=”35.000227″ long=”102.911035″ icon=”https://savetibet.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/07-08-marker.png”]7. Four detained and and fear for disappearance following self-immolation of Sangay Gyatso in Kanlho (October 2012)

8. Five detained and fear for disappearance after the self-immolation of Tamdin Dorje in Kahlho (October 2012)

Tsoe, Kanlho prefecture[/mgl_marker]

[mgl_marker lat=”34.827368″ long=”102.839624″ icon=”https://savetibet.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/16z-marker.png”]16. One sentenced and four feared to have been disappeared following the self-immolation of Sungdue Kyab in Kanlho (December 2012)

Bora, Kanlho[/mgl_marker]

[mgl_marker lat=”34.808765″ long=”102.691995″ icon=”https://savetibet.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/10z-marker.png”]10. One disappeared following self-immolation of Lhamo Tseten in Sangchu (October 2012)

Amchok, Sangchu county, Kanlho prefecture[/mgl_marker]

[mgl_marker lat=”34.589164″ long=”102.485315″ icon=”https://savetibet.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/15z-marker.png”]15. Three sentenced and five feared to have been disappeared following the self-immolation of Tsering Namgyal in Kanlho (November 2012)

Luchu, Kanlho[/mgl_marker]

[mgl_marker lat=”35.035655″ long=”101.471826″ icon=”https://savetibet.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/12-14-18-23Z-marker.png”]12. One sentenced following four self-immolations in Malho (November-December 2012)

14. Five detained and fear for disappearance following self-immolation of Sangay Dolma in Malho (November 2012)

18. One detained (and released) after the self-immolation of Wangchen Kyi in Malho (December 2012)

23. Five detained (four released) following the self-immolation of Phagmo Samdup in Malho (February 2014)

Tsekhog, Malho prefecture[/mgl_marker]

[mgl_marker lat=”32.786157″ long=”102.526514″ icon=”https://savetibet.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/19-marker.png”]19. Three sentenced following self-immolation of Tsering Phuntsok in Ngaba (January 2013)

Marthang/Changchu, Ngaba prefecture[/mgl_marker]

[mgl_marker lat=”33.573475″ long=”102.957727″ icon=”https://savetibet.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/21-marker.png”]21. At least seven Tibetans detained and feared to have been disappeared after the self-immolation of Kunchok Sonam in Ngaba (July 20, 2013)

Dzoege, Ngaba prefecture[/mgl_marker]

[mgl_marker lat=”32.923439″ long=”100.748102″ icon=”https://savetibet.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/17-22-marker.png”]17. Three sentenced following the self-immolation of Lobsang Geleg in Golog (December 2012)

22. Three detained and feared to have been disappeared following self-immolation of Tsering Gyal in Golog (November 2013)

Pema, Golog prefecture[/mgl_marker][/mgl_gmap]

1. New laws published in regional newspaper

The guidelines on prosecuting alleged ‘intentions’ relating to the death of another person were announced in December 2012, a month after Xi Jinping’s accession to power in November 2012 at the Party Congress in Beijing. November 2012 saw the highest one-month total of self-immolations by Tibetans (28) since the wave of self-immolations began in Tibet in February 2009.

The new guidelines were announced in the state-run newspaper, Gannan Daily, in Gansu on December 3, 2012, and have led to charges of ‘intentional homicide’ against Tibetans accused of association with self-immolation. The newspaper stated:

“So that the recent self-immolation cases that have occurred in Tibetan areas may be handled in accordance with the law and in order to ensure social stability, the Supreme People’s Court, Supreme People’s Procuratorate, and Ministry of Public Security of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) have, based on relevant laws and regulations, jointly issued an ‘Opinion on Handling Self-Immolation Cases in Tibetan Areas in Accordance with the Law.”

In the opinion piece, entitled ‘Those who incite self-immolations must be severely punished under the law,’ self-immolations were described as:

“Cases of significant evil that result from collusion between hostile forces inside and outside our borders whose attempts to use premeditated, organized plots to incite splittism, undermine ethnic unity, and seriously disrupt social order. [The cases] have seriously affected the present overall situation of ethnic unity and social stability in Tibetan areas. Those who carry out self-immolations in these cases are unlike the ordinary world-weary person who commits suicide. Their common motivation is to split the nation and they endanger public safety and social order, classifying their self-immolations as illegal criminal acts. Organizing, plotting, inciting, coercing, enticing, abetting, or assisting others to carry out self-immolations is, at its essence, a serious criminal act that intentionally deprives another of his or her life.”[18]

The ‘opinion’ by the Supreme People’s Court, the Supreme People’s Procuratorate, and Ministry of Public Security, as detailed in the Gansu Daily article, lists the following behavior as punishable:

- Anyone who organizes, plots, incites, coerces, entices, abets, or assists others to commit self-immolations shall be held criminally liable for intentional homicide in accordance with the Criminal Law;

- Anyone who actively commits self-immolation in which the circumstances are serious and that causes major harm or serious danger to society shall be held criminally liable in accordance with the law;

- Anyone who commits self-immolation in a public space and endangers public safety shall be held criminally liable for using dangerous methods to endanger public safety in accordance with the Criminal Law;

- Anyone who prepares, implements, or creates conditions for committing self-immolations shall be treated as if he or she were preparing to commit a crime;

- Anyone who commits self-immolation and, while burning, grabs hold of another person, shall be held criminally liable for intentional homicide in accordance with the Criminal Law;

- Anyone who commits self-immolation in a public place who does not endanger public safety but gathers many people to seriously disrupt public order or traffic order shall be held criminally liable for gathering a crowd to disrupt public order or traffic order in accordance with the Criminal Law; and

- Anyone who, in order to commit self-immolation, illegally carries gasoline or other flammable items into a public space or onto a public transportation vehicle shall be held criminally liable for illegally carrying dangerous items that endanger public safety in accordance with the Criminal Law.

The first cases of sentencing for ‘intentional homicide’ following a self-immolation were for three monks of the Kirti monastery in Sichuan province that the authorities blamed for taking the body of a self-immolator back to his monastery, which Tibetan sources described in terms of providing shelter and safety for him.[19]

In some of the earlier cases of Tibetans sentenced on charges of “intentional homicide,” the Tibetans had been detained prior to the new rulings and were only sentenced afterwards, indicating a period of deliberation as the authorities appeared to be seeking to create an ex post facto legal justification for severe penalties including the death sentence, for instance in the case of Lobsang Kunchok (see list below). In some cases, indicating the priority of the authorities in preventing information about self-immolations reaching the outside world, Tibetans appear to have been targeted for sharing information or taking photographs and then charged with “intentional homicide.”

The detention and sentencing of at least 98 Tibetans between April 2010 and February 2014 follow different self-immolations that are the consequence of harsher and unprecedented measures imposed in an attempt to attribute blame for the self-immolations to ‘outside forces.’ They include monks sentenced to prison for praying for those who self-immolated, an elderly man sentenced to four years for offering condolences to the bereaved, and friends and family of self-immolators sentenced to long prison terms despite no evidence presented either in official sources or available unofficially that they were associated with the self-immolation.[20]

At least 15 Tibetans have been sentenced under charges of “intentional homicide,” at least 11 under the new guidelines. In some cases detailed below – such as the monks of Kirti monastery sentenced following the self-immolation of the monk Phuntsog on March 16, 2011 – individuals were sentenced in a county court, which appears to be a violation of Article 20 of the PRC Criminal Procedure Law, which requires intermediate level courts to hear trials on criminal charges punishable by life imprisonment or the death penalty — a category that includes “intentional homicide.”[21]

There was a spike in these cases against Tibetans in winter 2012-2013 that can be directly attributed to a cluster of self-immolations occurring in the provinces of Qinghai and Gansu (the Tibetan region of Amdo) at that time. The new guidelines led to harsh sentences.

2. Questionable legal basis

Authorities appear to struggle to justify a legal basis to these new measures. According to Article 62 (3) of the Chinese Constitution, it is in the National People’s Congress’ power to “enact and amend basic statutes concerning criminal offences, civil affairs, the state organs and other matters.” Given the nature of the acts now subject to punishment, which are hitherto unknown to the Criminal Law of the PRC, the ‘opinion’ appears to be more than an interpretation of existing criminal law. It is particularly notable that these new measures, which hence establish new punishable acts in the Chinese Criminal Law, have been introduced without observing the prescribed constitutional process. For example, changes in the Chinese Criminal Procedure Law were relatively widely debated and eventually passed in March 2012 by the National People’s Congress and came into force January 2013. No such process was observed in case of the amendments regarding the penalizing of Tibetan self-immolations, as there has been neither a legislative process that was observed nor any, if only restricted, public debate.

3. Involvement of the new leadership

The approval of these new guidelines must also be viewed in connection with the National People’s Congress held in Beijing in November 2012. At this Congress, Xi Jinping was announced as leader of the CCP. The approval of the new guidelines, involving three of the highest institutions in the Chinese political system, the Supreme People’s Court, the Supreme People’s Procuratorate and the Ministry for Public Security, may reflect a political imperative of the new leadership under Xi to continue hard line policies and crackdown by security forces in Tibet.

In April 2013, a county-level government in Dzoege, Ngaba (Chinese: Ruo’ergai, Aba), Sichuan Province, announced new forms of punishment and persecution for Tibetan individuals and communities if a Tibetan self-immolator is a relative or from the local area. The provisions, which Tibetan writer Tsering Woeser termed as “absurd and terrifying,’ represent a form of collective punishment that could have potentially devastating consequences on Tibetan communities.[22]

Sanctions include the inability of individuals to hold government positions or receive official aid, deprivation of government assistance to villages where the self-immolation protests occur, and farmland or pasture registered in the name of the self-immolator will be taken by the authorities.

The new punishment framework is consistent with the Chinese authorities’ attempts to impose legislative measures that constrict Tibetans in other areas too, such as religion. Over the past few years, the Party authorities have been implementing laws and regulations in order to “earnestly maintain the normal order of Tibetan Buddhism, and guide Tibetan Buddhism to keep in line with the ‘socialist society.’”[23] These regulatory measures provide for increased state regulation of Tibetan Buddhism, and an expansion of the aggressive political campaign to end the Dalai Lama’s influence among Tibetans.[24]

In an analysis of the new measures, the Washington-based Congressional-Executive Commission on China concludes that the application of collective punishment outlined in the provisions is not supported in international law. The CECC said: “Precedent for banning collective punishment extends back more than a century to the 1907 Hague Conference, which resulted in a convention stating: ‘No general penalty, pecuniary or otherwise, shall be inflicted upon the population on account of the acts of individuals for which they cannot be regarded as jointly and severally responsible.’”

The CECC also comments on the oversight that would have been required to institute the provisions, which appears to be absent, stating: “What level of oversight or approval would the Provisions have required? The PRC Constitution subordinates a local government to the local congress at the same level, and the PRC Legislation Law provides higher legislative authority to a local congress than to the local government at the same level. Based on the Constitution and PRC Regional Ethnic Autonomy Law (REAL), if the Ruo’ergai County People’s Government issued a ‘decision’ or ‘order’ (jueding, mingling), it would have been required to ‘report’ the action to the Ruo’ergai County People’s Congress and to the Aba Tibetan and Qiang Prefecture People’s Government. The Constitution and REAL do not explicitly require either body to formally approve the local government’s work. In comparison, if the Ruo’ergai County People’s Congress had passed a ‘special decree’ (danxing tiaoli), also translated as ‘separate regulation’) on the punishments, the PRC Legislation Law and the REAL both would have required approval by the standing committee of the provincial-level people’s congress—in this case the Standing Committee of the Sichuan Province People’s Congress. The REAL also requires that approval of a “special decree” be reported for the record to the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress.

The United States Congressional-Executive Commission on China (CECC) summarized the provisions as follows:[25]

CECC: “Precedent for banning collective punishment extends back more than a century to the 1907 Hague Conference, which resulted in a convention stating: ‘No general penalty, pecuniary or otherwise, shall be inflicted upon the population on account of the acts of individuals for which they cannot be regarded as jointly and severally responsible.’”

- Restricting career, employment, and housing opportunities for a self-immolator’s family members by canceling (quxiao) their eligibility to apply for national-level government or military employment (Art. 1);

- Obstructing the ability to maintain housing for persons officials deem to have been ‘actively involved’ in a self-immolation by canceling household benefits for three years and social benefits for one year (Art. 4);

- Preventing or obstructing the ability of a self-immolator’s family members to secure a livelihood by revoking (shouhui) the right to use land for farming or grazing (Art. 9);

- Preventing or obstructing the ability of residents of a village where a self-immolator lived to secure a livelihood by freezing (dongjie) the right of villagers to use land for farming or grazing (Art. 9);

- Preventing or obstructing the ability of a self-immolator’s family members and the house holds of persons deemed to have been “active participants” in a self-immolation to secure a livelihood by withholding approval (buyu shenpi) to conduct business activity for three years (Art. 10);

- Preventing the ability of a self-immolator’s family members and the households of persons deemed to have been “active participants” in a self-immolation from accessing full use of real estate by only confirming (quequan) (rural) land and building rights, but not issuing certification (zheng) (Art. 10);

- Imposing financial and other hardships on households of persons officials deem to have been “actively involved” in a self-immolation by designating the households as “untrustworthy” (buchengxin) and withholding the grant (buyu fafang) of new loans for three years; and by only receiving (zhi shou) payments on existing loans but not disbursing (bu fang) funds from the loans (Art. 6);

- Preventing a self-immolator’s immediate family members from obtaining certain positions of political influence by canceling their eligibility to seek election to a people’s congress at any level or to the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, or to serve as a village -level Party cadre (Art 2); and

- Restricting the freedom of movement of a self-immolator’s immediate family members by withholding approval to travel abroad or to the Tibet Autonomous Region for three years (Art. 11).

Provisions that would collectively punish the members of a community, village, or monastic institution include the following:

- Imposing financial and other hardships on a village, community, or monastic institution associated with a self-immolator by canceling or postponing (zanhuan) national-level investment in that village, community, or monastic institution (Art. 5);

- Imposing financial and other hardships on a village or community associated with a self-immolator by halting (tingzhi) “all investment and civil society capital projects” (Art. 5);

- Imposing financial and other hardships on a community, village, or monastic institution associated with a self-immolator by designating them as “untrustworthy” and withholding the grant of new loans for three years; and by only receiving payments on existing loans but not disbursing funds from the loans (Art. 6);

- Imposing financial hardships and imperiling function by requiring a community, village, or monastic institution where a self-immolation takes place to pay a “security deposit” (baozhengjin) of 10,000 to 500,000 yuan (US$ 1,600 to 80,000) that would be returned if another self-immolation does not occur within two years. If another self-immolation occurs, the security deposit would be placed in the national treasury and payment of an additional security deposit would be required (Art. 7);

- Imposing financial hardships and imperiling function by linking self-immolations to financial support provided to community and village Party cadres, Democratic Management Committee members, and “responsible religious leaders” (zeren jingshi) (Art. 8);

- Imposing financial hardships and imperiling function in monastic institutions associated with a self-immolator by ordering their businesses to close down (tingye) (Art. 15); and

- Imposing a reduction in religious function in monastic institutions associated with a self-immolator with temporary “strict limitations” (yange xian zhi) on monks’ and nuns’ activities, and on large-scale Tibetan Buddhist activities across an undefined broader “area” (Art. 14).

Provisions that would establish an intimidating political and legal environment targeting families, households, communities, villages, or monastic institutions include the following:

- Implementing a “strike hard” (yanda) campaign anywhere that a self-immolation takes place, and imposing the “strictest” (zui yanli) comprehensive (zonghe) administrative law enforcement (xingzheng zhifa) and corrective punishment (zhengzhi) (Art. 12);

- Intimidating categories of employees including civil servants working in national-level government offices, career staff, and support staff by requiring them to “strengthen” the education of their family members and threatening to “severely deal with” (yansu chuli) an employee if a family member self-immolates (Art. 3);

- Requiring residents of villages, communities, and monastic institutions where a self-immolation takes place to attend “legal study classes” (fazhi xuexi ban) (Art. 13); and

- Requiring family members and others linked to a self-immolation by “minor evidence” or “actions that do not constitute a crime” to attend a minimum of 15 days’ “legal education classes” (fazhi jiaoyuxue ban) located at a “different place” (yidi) (Art. 13).

Through the announcement, Chinese authorities provide no information on the legal basis for such collective punishments, nor do they provide information on whether Tibetans may appeal against such collective punishment.[26]

In its analysis, the CECC could not identify a constitutional basis for the application of these new punishments:

Commission research failed to locate any article within the Constitution that appears either to explicitly permit the collective punishment of families, households, communities, villages, or monastic institutions irrespective of individual activity; or that explicitly protects citizens from collective punishment. Based on Commission analysis, the Constitution does not establish an explicit requirement that the government must adhere to a legal process when punishing citizens, or that explicitly provides citizens the right to appeal against punishment. The 2004 amendment of Article 13 states, “Citizens’ lawful private property is inviolable” and that “the state . . . protects the rights of citizens to private property.” The Provisions, however, could have the capacity to impose financial peril on a family, community, or monastic institution by preventing or obstructing the rightful use of property that may include “private property.”[27]

Due to restrictions on information in the area, the full impact of the new regulations is not known; it has not been possible to confirm whether the measures have been applied in Dzoege.

Tibetans are taking increasing risks to protest the detention of individuals in their communities, and to assert their concerns for key religious and civil society figures. In many of the cases detailed below, relatives, friends or elders from the community have taken bold steps to seek to establish the whereabouts of those who have disappeared due to the new measures against self-immolation, despite the dangers.

A Tibetan source told ICT: “So many disappearances have taken place, when no one knows when members of their family and friends have gone. When they ask the authorities, they are not told anything, which is creating an atmosphere of fear and tension in so many areas.”

Even when relatives and friends are informed of the arrests, according to information from Tibetan sources, Tibetan prisoners accused of involvement in self-immolations have not been allowed visits from family or friends.

According to information gathered by ICT, many Tibetans who decide to self-immolate know the political climate and appear to have mostly made the decision not to tell family or friends beforehand for fear they may face retribution.[28]

In Tibetan culture, when a person dies the body has to be left undisturbed while special prayers and ceremonies are held for the transference of the person’s consciousness on the path to a beneficial rebirth. This is one of the reasons why in a number of cases, Tibetans on the scene of a self-immolation have risked their lives in attempts to protect the body of the person who has set fire to him- or herself, and to take them to a place of safety – either a monastery or the person’s home – where traditional rituals can be carried out. It compounds the agony for Tibetans when monks are blocked from praying for Tibetans who have died, as they have been in Ngaba (Chinese: Aba) and other areas.

In some cases detailed below, for instance following the self-immolation of Dorje Rinchen in Labrang, full details of the circumstances of the deaths of the self-immolators and the role of those who may have sought to block police from taking the body, or obtain the body to carry out traditional prayers, are not known.

The International Campaign for Tibet urges the People’s Republic of China:

- to release immediately all Tibetans who have been detained and sentenced on grounds of “incitement to” or “aiding” self-immolations, and whose actions themselves do not represent punishable behavior according to Chinese Criminal Law and international law;

- to cease, and revoke the policies that provides for, the detention and sentencing of Tibetans who are allegedly associated with self-immolations, and for collective punishments against the families and communities of self-immolators;

- to make public its constitutional and legal justification, if any, for the guidelines that impose of penalties on Tibetans allegedly associated with self-immolation;

- to make public its constitutional and legal justification, if any, for the procedures that impose of collective penalties on Tibetans and Tibetan communities from the locality of Tibetans who self-immolate;

- to disclose whether non-Tibetan citizens of the People’s Republic of China have been subjected to detention and sentencing for alleged ‘association’ with acts of self-immolation that have occurred in mainland China;

- to investigate thoroughly reports of torture and mistreatment in detention and bring those responsible to justice, pursuant to the People’s Republic of China’s obligations under the Convention against Torture, of which it is a state Party; and

- to safeguard principles of due process according to international law, including the right to access to legal representation of choice, adequate medical treatment if needed, as well as access to legal remedies.

The International Campaign for Tibet urges the international community, concerned governments, parliaments and United Nations institutions:

- to call for the immediate release of all those detained because of their association with Tibetans who have self-immolated or who have attempted to self-immolate;

- to ask the government of the People’s Republic of China to justify the legality of the provisions to sentence Tibetans for alleged “organizing, plotting, inciting, coercing, enticing” others to carry out self-immolations towards their Chinese counterparts, including as part of expert discussions at dialogues on rule of law and human rights;

- to challenge the government of the People’s Republic of China on its contraventions of international law implicit in the procedures that impose collective penalties against Tibetans;

- to urge the government of the People’s Republic of China to safeguard minimum standards for due process and judicial rights of those detained or are subject to penal investigation;

- to ask the government of the People’s Republic of China to schedule promptly the visit to Tibet by UN Human Rights Commissioner.

Note on Geographical Terms

For clarity and consistency, this report uses the Tibetan name for geographical jurisdiction at the town, county and prefecture level, and the Chinese name at the province level. Please see the chart at the end of the Case Details for a guide to Tibetan and Chinese place names.

Footnotes

[1] Xinhua, February 7, 2013: “青海藏区系列自焚案内幕揭秘:达赖集团索命骗钱”, http://politics.gmw.cn/2013-02/07/content_6660525.htm (accessed on June 2, 2014); “Gansu’s Gannan official: 18 Self-Immolation Cases Cracked”, China News Service, January 23, 2013, cited by the Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual Report, 2013, p 302, cecc.gov;

[2] The state media declared in February 2012 that the situation in Tibet is so grave that officials must ready themselves for “a war against secessionist sabotage.” China Tibet Online, February 10, 2012: “Tibet officials ‘prepare for war’”;

[3] Global Times, October 23, 2012: “Leaders focus on stability”;

[4] Information Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China, October 22, 2013: “Development and progress of Tibet” (“White Paper”);

[5] “Stability maintenance” or “weiwen” is not only applied to Tibet, but can be described as a “raft of policies and practices” that enable the security apparatus to prevent protest and dissent in the entire PRC; see New York Times, February 28, 2011: “Well-Oiled Security Apparatus in China Stifles Calls for Change”; on the “astronomical” spending on “stability maintenance”, see Human Rights in China, November 20, 2012: “China’s Stability Maintenance System Faces Financial Pressure”;

[6] International Campaign for Tibet, June 20, 2014: “Escalation of surveillance over monks as authorities announce opening of police stations in Tibetan monasteries”;

[7] Amnesty International, 2012: “Standing their ground – Thousands face violent eviction in China”;

[8] In 2001, in an isolated and single incident, four individuals with an alleged Falun Gong background were charged with intentional homicide, because of their alleged incitement to self-immolation, see Xinhua, ibid.;

[9] Xinhua, August 31, 2011: “Another two Tibetan monks sentenced in self-immolation, murder case”;

[10] Gansu Daily, December 3, 2012: “煽动自焚者必将受到法律严惩”, http://gn.gansudaily.com.cn/system/2012/12/03/013508017.shtml (accessed on June 2, 2014);

[11] Xinhua, May 18, 2001: “Dalai Clique’s Spies Caught, Plot Crushed”;

[12] See for example Xinhua, July 18, 2012: “Self-immolation truth: Tibetan Buddhism kidnapped by politics”, stating: “Copycat suicides spread, triggering public concern that teenagers and other vulnerable people are at risk”;

[14] See for example the cases of Dawa Tsering, Lobsang Gyatso, Chimey Palden, Tenpa Darjey, Dickyi Choezom or Passang Lhamo, as documented at International Campaign for Tibet, “Self-immolations by Tibetans” (online fact sheet, www.https://savetibet.org);

[15] An official documentary depicts the first self-immolator in Tibet, Tapey, in hospital, wearing monks’ robes, with his head, neck, arms and legs heavily scarred. It is notable that in the video, despite the pressure he must have been under to express his regret, he simply talks about his physical condition, saying that most parts of his body have physically healed and he can write slowly with one of his hands. His mother is shown speaking to the interviewer in Tibetan, saying: “He said he deeply regrets what he’s done. “The Dalai clique and the self-immolation event, part 2,” May 10, 2012, Chinese Central Television’s YouTube account, see: www.youtube.com/watch?NR=1&feature=endscreen&v=6H1eQpGgxFs at 0 mins, 55 seconds;

* See section B, “The Opinion: New guidelines published in December 2012”

[16] Associated Press, January 31, 2013: “First Tibet ‘self-immolation’ convictions in China, as fiery deaths near 100”;

[17] CECC report, October 11, 2011, http://www.cecc.gov/publications/commission-analysis/county-court-convicts-monks-of-intentional-homicide-for-sheltering;

[18] Gansu Daily, ibid.; guidelines translated by “Dui Hua”, http://www.duihuahrjournal.org/2012/12/china-outlines-criminal-punishments-for.html;

[19] In a response to a question from the press on August 29, 2011, a U.S. State Department spokesperson said the government was “concerned” by the conviction for “intentional homicide”. The spokesperson also said: “We urge the Chinese government to ensure transparency and to uphold the procedural protections and rights to which Chinese citizens are entitled under China’s Constitution and laws and under international standards”;

[20] Just over a month following the publication of the Gansu guidelines in December, 2012, the Chinese state media had reported nearly 90 arrests linked to self-immolations in Qinghai and Gansu provinces. Xinhua, February 7, 2013: “青海藏区系列自焚案内幕揭秘:达赖集团索命骗钱”, http://politics.gmw.cn/2013-02/07/content_6660525.htm (accessed on June 2, 2014); “Gansu’s Gannan official: 18 Self-Immolation Cases Cracked”, China News Service, January 23, 2013, cited by the Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual Report, 2013, p 302, cecc.gov;

[21] Official media reports have provided no information on why trials on charges punishable by the death penalty or life imprisonment were heard before a county-level court. An additional unusual aspect of the trials is that the county court that reportedly tried the cases was not the county court with jurisdiction over the site where the alleged crimes were committed: Kirti Monastery is in Aba, not Ma’erkang, county. The Ma’erkang County People’s Court is located in the prefectural capital, along with the Aba T&QAP Intermediate People’s Court.” Report by Congressional-Executive Commission on China, October 11, 2011, http://www.cecc.gov/publications/commission-analysis/county-court-convicts-monks-of-intentional-homicide-for-sheltering;

[22] International Campaign for Tibet, February 24, 2014: “‘Absurd and terrifying’ new regulations escalate drive to criminalize self-immolations by targeting family, villagers, monasteries”, https://savetibet.org/absurd-and-terrifying-new-regulations-escalate-drive-to-criminalize-self-immolations-by-targeting-family-villagers-monasteries/; a picture of the regulations has been leaked out of Tibet and can be viewed here: https://www.flickr.com/photos/118672071@N02/12766538965/;

[23] Hu Jintao, emphasizing the Party’s role in controlling Tibetan Buddhism at the Fifth Work Forum on Tibet in January, 2010, Xinhua, January 22, 2010: “China to achieve leapfrog development, lasting stability in Tibet”;

[24] Regulatory measures on “Tibetan Buddhist Affairs” at monasteries and nunneries in nine of the 10 Tibetan autonomous prefectures located outside the Tibet Autonomous Region have either taken effect or are moving through the legislative process. For instance, the central government issued national-level regulations effective November 1, 2010, that, along with the prefectural-level regulations, impose closer monitoring and supervision of each monastery’s Democratic Management Committee—a government-required group legally mandated to ensure that monks, nuns, and teachers obey government laws, regulations, and policies on religion and religious practice. The national regulations detail for the first time a government-supervised process that every Tibetan Buddhist monastic institution must follow to establish a quota on the number of monks and nuns entitled to reside at a monastery or nunnery. National- and prefectural-level regulations impose a complicated approval process that monks, nuns, and Tibetan Buddhist teachers must complete before they receive permission to travel to another Tibetan Buddhist institution to study or teach. Approval of the new regulatory measures is concurrent with increased government repression of Tibetan Buddhists’ religious freedom following the wave of protests (and some rioting) that began in Lhasa on March 10, 2008, and spread to locations across the Tibetan plateau;

[25] Congressional-Executive Commission on China Special Report, ‘County Government Threatens Self-Immolation Communities With Collective Punishment’, April 14, 2014, http://www.cecc.gov/sites/chinacommission.house.gov/files/County%20Gov%20Threatens%20Collective%20Punishment_14apr14.pdf;

[26] The Congressional-Executive Commission on China observed: “The PRC Criminal Law and PRC Criminal Procedure Law do not contain language addressing the notion of collective punishment of communities, villages, or institutions based solely on proximity to an action the government treats as illegal, or based solely on a family relationship with a person who committed such an act. The Provisions contain no reference to any means by which a family, households, community, village, or monastic institution facing punishment may appeal against a punishmnent.” Congressional-Executive Commission on China Special Report, ‘County Government Threatens Self-Immolation Communities With Collective Punishment’, April 14, 2014, http://www.cecc.gov/sites/chinacommission.house.gov/files/County%20Gov%20Threatens%20Collective%20Punishment_14apr14.pdf;

[28] According to research of the International Campaign for Tibet in self-immolations including interviews with family members or friends in exile. See International Campaign for Tibet, December 2012: “Storm in the Grasslands”.