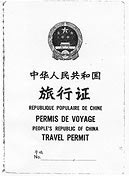

Chinese document issued to Tibetan refugees wishing to travel to Tibet.

The Chinese embassy in Kathmandu has shifted between accepting all applications and doling out the transit permits to closing the application lines without explanation. The Chinese embassy in New Delhi has appeared to take a measured response and issued very few transit permits.

China began allowing Tibetan refugees to apply to return to Tibet in the 1980s and issued travel documents liberally to the few Tibetans who applied. The issuance of travel documents became stricter in the 1990s and very few Tibetans were officially allowed by the Chinese authorities to return. The newest version of this policy grants two types of permits: a temporary, one-year pass and a relocation pass for those wishing to permenently return to Tibet. Tibetans who wish to return to their hometowns for “visits, sightseeing, or religious activities,” are welcomed, according to Xinhua, China’s official news body, on February 5th. The article noted that Tibetans who return must, “act in a manner that supports the motherland.”

In mid-February, transit and relocation permits were issued within a week’s time from the Chinese embassy in Kathmandu. Approximately 20 Tibetans were applying daily in the first weeks of the new policy. Not all who applied were issued permits. In February and March, approximately 150 transit passes were issued to Tibetans from the Chinese embassy in Kathmandu. At the Chinese embassy in New Delhi, fewer Tibetans applied and fewer transit passes were issued. However, for those transit passes that were issued in New Delhi, the Tibetans were instructed to go to the Nepalese embassy to obtain a stamp for a 12-day visa that would allow passage through the Kingdom of Nepal, which would be placed on the Chinese issued transit pass. This coordination between Chinese and Nepalese embassies indicates a significant degree of communication and cooperation between Beijing and Kathmandu.

Both relocation and transit permits are apparently issued only for one’s hometown, preventing a returnee from settling in Lhasa or cities other than their hometown. If a Tibetan is originally from Lhasa, stricter controls apply, requiring the applicant to provide an invitation letter from the city of Lhasa stating the exact address where they will relocate. No such letter is required for other towns, according to Tibetans who have been applying in Kathmandu.

In mid April, the Chinese embassy in Nepal abruptly stopped accepting applications to return to Tibet, and no more passes were issued from the existing applications. Yet, on May 13th, the Chinese embassy again opened the doors to the application process but told applicants that they would have to wait from one to two months while a background check was carried out and references in Tibet were contacted. Applications are still being accepted.

The director of the Tibetan Autonomous Regional Committee for Receiving Returned Tibetans, Pasang (Ch: Basang) stated at a February 4th meeting in Lhasa that it “welcomes overseas Tibetan compatriots contributing to the development of Tibet and their home towns. The Government also welcomes [those] doing practical work for economic development and social progress in the motherland” (Xinhua, 4 Feb). The director went on to say that Tibetans would not be asked of prior political activity carried out in exile and they would be welcomed back if they gave up “their stance of ‘Tibet independence’ and genuinely cease engaging in activities to split the motherland.”

“We don’t know why they keep on changing the process,” Wangchuk Tsering, representative of the Dalai Lama in Nepal, told ICT. “But we do know that the more applicants and the more interviews that are conducted, the more extensive web of knowledge is being built around us, both inside and outside Tibet.”

Tibetans in Kathmandu told ICT that the Chinese embassy said that they would not be asked of any political activity before the year 2000. “They told me I just needed to support the Motherland and not talk about the Dalai Lama, and I could go back,” thirty-year-old Tsepan Dorje told ICT.

However, one Tibetan who went to apply was turned down on the spot. “They (the Chinese embassy) must have already done some homework on me even before I applied,” one Tibetan told ICT. “I don’t actually know why they refused me. I haven’t done anything political.”

When applying for the relocation pass, Tibetans in Kathmandu told ICT that Chinese embassy personnel asked them to turn over their Green Book. Green Books are issued by the Tibetan government in exile and used for recording the casting of election ballots and annual tax contributions. To apply for the one-year transit pass, Tibetans were asked to, at a minimum, submit a photocopy of the Green Book.

“No Tibetan in their right mind would surrender their Green Book to the Chinese authorities,” said Dorje, a long-time Tibetan refugee living in Kathmandu. Some Tibetans fear that the Green Books collected by China could be used against those Tibetans at a later date, if policies were to change.

The ambiguous policy is also likely an attempt to politically neutralize Tibetans who intend to officially return to Tibet at some time. “Tibetans are told that they won’t be asked any questions of their political activities in the last couple years,” stated Wangchuk Tsering. “If a Tibetan chooses to subscribe to this, they are being neutralized politically because going back officially means acting in an official manner, namely, not advocating for political justice.”

Tibetans in Nepal have expressed a fear that while Beijing may proclaim that Tibetans can return without being persecuted for past activities, local authorities may monitor or harass them. “It is all part of finding out who is connected to whom and to make sure any people with political views are ferreted out,” a newly arrived Tibetan refugee in Kathmandu told ICT.