CHINA’S CONTROL

STATE IN LHASA

THE BLACK BOX OF TIBET’S PRISON SYSTEM:

DETENTION CENTER NOTORIOUS FOR TORTURE NEXT TO 5-STAR GLOBAL BRAND HOTEL

CHINA’S CONTROL

STATE IN LHASA

THE BLACK BOX OF TIBET’S PRISON SYSTEM:

DETENTION CENTER NOTORIOUS FOR TORTURE NEXT TO 5-STAR GLOBAL BRAND HOTEL

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This International Campaign for Tibet report uses new satellite imagery of Lhasa, once Tibet’s cultural and historic heart, to reveal the dramatic remodeling of the city as an urban hub of hyper-securitization at the same time as a tourist boom. The report unlocks the significance of images of Lhasa today, revealing the unprecedented scope of China’s machinery of compliance in Tibet.

- The most notorious detention center in Lhasa – with a reputation for brutal torture of Tibetan monks, nuns and laypeople – is adjacent to the international 5-star hotel, the InterContinental Lhasa Paradise. The image of Gutsa Detention Center, with its guard towers visible, next to the space age style pyramid design of the internationally branded hotel, is a vivid illustration of the co-existence of a security state involving total surveillance with mass Chinese tourism in Tibet today.

- Evidence of the expansion and modernization of prison and detention facilities in a political climate of tightened control, in which the Chinese prison system in Tibet is an almost impenetrable black box. China seeks to hide the existence of such extensive prison facilities in a city at the forefront of a push to attract tourists to Tibet.

- Although in 2013 China officially ended its system of ‘re-education through labor’ – after the imprisonment of millions of people without trial over 50 years – the footprint of the main ‘re-education through labor’ facility in Lhasa, Trisam, remains and may have been re-purposed as a compulsory ‘education’ center.

- A Tourism and Culture Expo held in Lhasa last month stated the intention to increase tourism – while at the same time emphasizing how security concerns are paramount, given the significance of Tibet as an important “security barrier”.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This International Campaign for Tibet report uses new satellite imagery of Lhasa, once Tibet’s cultural and historic heart, to reveal the dramatic remodeling of the city as an urban hub of hyper-securitization at the same time as a tourist boom. The report unlocks the significance of images of Lhasa today, revealing the unprecedented scope of China’s machinery of compliance in Tibet.

- The most notorious detention center in Lhasa – with a reputation for brutal torture of Tibetan monks, nuns and laypeople – is adjacent to the international 5-star hotel, the InterContinental Lhasa Paradise. The image of Gutsa Detention Center, with its guard towers visible, next to the space age style pyramid design of the internationally branded hotel, is a vivid illustration of the co-existence of a security state involving total surveillance with mass Chinese tourism in Tibet today.

- Evidence of the expansion and modernization of prison and detention facilities in a political climate of tightened control, in which the Chinese prison system in Tibet is an almost impenetrable black box. China seeks to hide the existence of such extensive prison facilities in a city at the forefront of a push to attract tourists to Tibet.

- Although in 2013 China officially ended its system of ‘re-education through labor’ – after the imprisonment of millions of people without trial over 50 years – the footprint of the main ‘re-education through labor’ facility in Lhasa, Trisam, remains and may have been re-purposed as a compulsory ‘education’ center.

- A Tourism and Culture Expo held in Lhasa last month stated the intention to increase tourism – while at the same time emphasizing how security concerns are paramount, given the significance of Tibet as an important “security barrier”.

NOTORIOUS DETENTION CENTER NEXT TO ‘PARADISE’ HOTEL

Tibetans who were held and tortured at Gutsa Detention Center, officially known as Lhasa Public Security Bureau Detention Center, have identified the location of the security facility where they were held as being adjacent to the InterContinental Hotel on the satellite images. Given the height of the hotel buildings, it is conceivable that prisoners in the compound could be visible from some of the Hotel InterContinental Lhasa Paradise rooms.

Gutsa has gained a reputation for brutal torture under interrogation. It serves as the initial detention center for thousands of Tibetans imprisoned over the years for involvement in peaceful protest, or such actions as celebrating the Dalai Lama’s birthday. Reports from former prisoners held there include torture with electric batons, sometimes almost to death, attacks by dogs and beating and shock treatment while the prisoner is suspended naked from a ceiling.

A Tibetan nun held in Gutsa for celebrating the award of the Nobel Peace Prize to the Dalai Lama, recalled: “An especially painful torture consisted of wiring one finger on each of my hands, while I was seated on a chair, and connecting them to an electric installation. As the handle on the installation was turned a full circle, I felt every single part of my body being seized by a powerful electric current. The intensity of the shock would fling me across the room, invariably rendering me unconscious. The interrogators would, however, try to revive me by slapping me and throwing water on me. Often the wires would snap, and then they had to reconnect them. People subjected to this method of torture most often had to be taken directly to the hospital.”[1]

NOTORIOUS DETENTION CENTER NEXT TO ‘PARADISE’ HOTEL

Tibetans who were held and tortured at Gutsa Detention Center, officially known as Lhasa Public Security Bureau Detention Center, have identified the location of the security facility where they were held as being adjacent to the InterContinental Hotel on the satellite images. Given the height of the hotel buildings, it is conceivable that prisoners in the compound could be visible from some of the Hotel InterContinental Lhasa Paradise rooms.

Gutsa has gained a reputation for brutal torture under interrogation. It serves as the initial detention center for thousands of Tibetans imprisoned over the years for involvement in peaceful protest, or such actions as celebrating the Dalai Lama’s birthday. Reports from former prisoners held there include torture with electric batons, sometimes almost to death, attacks by dogs and beating and shock treatment while the prisoner is suspended naked from a ceiling.

A Tibetan nun held in Gutsa for celebrating the award of the Nobel Peace Prize to the Dalai Lama, recalled: “An especially painful torture consisted of wiring one finger on each of my hands, while I was seated on a chair, and connecting them to an electric installation. As the handle on the installation was turned a full circle, I felt every single part of my body being seized by a powerful electric current. The intensity of the shock would fling me across the room, invariably rendering me unconscious. The interrogators would, however, try to revive me by slapping me and throwing water on me. Often the wires would snap, and then they had to reconnect them. People subjected to this method of torture most often had to be taken directly to the hospital.”[1]

These two images show the location of Gutsa (Lhasa Public Security Bureau Detention Center) near a sports ground and the InterContinental Hotel, the white pyramids, recently in 2018. A teahouse and other facilities are tagged in the area of the detention center. In 1993, according to an expert observer, the non-cell-block areas were likely to provide accommodation for Public Security Bureau staff and support facilities. Access to that area in 1993 was through the same gate that served the detention center and was linked by driveways to the area with the cell blocks. There was only one gate off the main road in 1993 and both areas shared it. At the detention center today, that area has a separate gate on the main road and no part of the compound is directly linked to the Public Security Bureau Detention Center area. This could mean that the new area may still be the property of the Public Security Bureau and used as an office, but with no or little relation to the detention center. (Screenshots from Google Earth by ICT)

These two images show the location of Gutsa (Lhasa Public Security Bureau Detention Center) near a sports ground and the InterContinental Hotel, the white pyramids, recently in 2018. A teahouse and other facilities are tagged in the area of the detention center. In 1993, according to an expert observer, the non-cell-block areas were likely to provide accommodation for Public Security Bureau staff and support facilities. Access to that area in 1993 was through the same gate that served the detention center and was linked by driveways to the area with the cell blocks. There was only one gate off the main road in 1993 and both areas shared it. At the detention center today, that area has a separate gate on the main road and no part of the compound is directly linked to the Public Security Bureau Detention Center area. This could mean that the new area may still be the property of the Public Security Bureau and used as an office, but with no or little relation to the detention center. (Screenshots from Google Earth by ICT)

This satellite image of 2018 shows Gutsa Detention Center from a different angle with guard towers marked. The expansion and modernization of this notorious facility are evident in comparison to the 1993 image.

This satellite image of 2018 shows Gutsa Detention Center from a different angle with guard towers marked. The expansion and modernization of this notorious facility are evident in comparison to the 1993 image.

Watchtowers are visible on this photograph of Gutsa taken in 1993 and a patchwork of fields in the background, which do not exist now. The southern perimeter wall has a slight bend that helps to show the link between the images from 1993 and 2018, flagged here. Used with the kind permission of the photographer.

Watchtowers are visible on this photograph of Gutsa taken in 1993 and a patchwork of fields in the background, which do not exist now. The southern perimeter wall has a slight bend that helps to show the link between the images from 1993 and 2018, flagged here. Used with the kind permission of the photographer.

Gutsa Detention Center, as seen on Baidu Street View (August, 2018). To the right: the Intercontinental Hotel. (Screenshot: ICT)

Gutsa Detention Center, as seen on Baidu Street View (August, 2018). To the right: the Intercontinental Hotel. (Screenshot: ICT)

The official website of the InterContinental Hotel in Lhasa states: “InterContinental Lhasa Paradise offers not only the quiet, luxury and world-class cuisine but also warm smiles that make traveling to Lhasa a welcome escape.”[2] The InterContinental was used as a key element of a promotional video for tourism in Tibet during the Tibet Tourism and Cultural Expo in Lhasa last month, featuring the large imitation Potala Palace in the foyer area, and showing a Tibetan dancer outside the building.[3]

The official website of the InterContinental Hotel in Lhasa states: “InterContinental Lhasa Paradise offers not only the quiet, luxury and world-class cuisine but also warm smiles that make traveling to Lhasa a welcome escape.”[2] The InterContinental was used as a key element of a promotional video for tourism in Tibet during the Tibet Tourism and Cultural Expo in Lhasa last month, featuring the large imitation Potala Palace in the foyer area, and showing a Tibetan dancer outside the building.[3]

This image of Lhasa by night shows the expansion and development of the city. The ‘snow peak’ architecture of the InterContinental Hotel can be viewed at the top left of the image. Used with kind permission of the photographer, who asked to remain anonymous.

This image of Lhasa by night shows the expansion and development of the city. The ‘snow peak’ architecture of the InterContinental Hotel can be viewed at the top left of the image. Used with kind permission of the photographer, who asked to remain anonymous.

This image, taken recently in Lhasa, shows the frontage of the InterContinental Paradise Hotel in Lhasa.

This image, taken recently in Lhasa, shows the frontage of the InterContinental Paradise Hotel in Lhasa.

The sign at the front of the InterContinental Hotel is in Chinese and English, with no Tibetan on the main signage.

The sign at the front of the InterContinental Hotel is in Chinese and English, with no Tibetan on the main signage.

Security camera outside one of the units of the InterContinental Hotel.

Security camera outside one of the units of the InterContinental Hotel.

Security camera on the street outside sports stadium in Lhasa with the pyramid structures of the InterContinental Hotel in the background.

Security camera on the street outside sports stadium in Lhasa with the pyramid structures of the InterContinental Hotel in the background.

The push to advance tourism to Tibet has changed the dynamic of investment in Tibet, drawing more foreign companies such as British chain the InterContinental Hotels Group to enter the Tibetan economy. The InterContinental Hotel Group opened the first phase of the hotel in Lhasa in 2014,[4] and is one of several globally branded hotels now in Lhasa including the Starwood St Regis and the ‘Four Points’ by Sheraton.[5]

The Chinese authorities require all global chains to have a Chinese partner, and they also need to work with real estate developers whose capacity to achieve results depends on relationships with the apparatus of Party and state. In the case of the InterContinental, the Chinese partner has been controversial billionaire businessman Deng Hong, who heads the Chengdu Exhibition and Travel Group. Deng Hong was imprisoned in 2013, apparently for corruption, and has now been released and is back in the tourism business.[6] The InterContinental Hotels Group was contracted to manage 13 properties developed by Deng Hong’s company, including the Lhasa Paradise and the Jiuzhai Paradise in Ngaba (Chinese: Aba), the part of eastern Tibet where the wave of self-immolations by Tibetans began in 2009.

The boom in tourism in Lhasa today coexists with a security crackdown of unprecedented depth and scope, imposed following a wave of overwhelmingly peaceful protests that swept across the plateau in 2008, transforming the political landscape in Tibet.

The push to advance tourism to Tibet has changed the dynamic of investment in Tibet, drawing more foreign companies such as British chain the InterContinental Hotels Group to enter the Tibetan economy. The InterContinental Hotel Group opened the first phase of the hotel in Lhasa in 2014,[4] and is one of several globally branded hotels now in Lhasa including the Starwood St Regis and the ‘Four Points’ by Sheraton.[5]

The Chinese authorities require all global chains to have a Chinese partner, and they also need to work with real estate developers whose capacity to achieve results depends on relationships with the apparatus of Party and state. In the case of the InterContinental, the Chinese partner has been controversial billionaire businessman Deng Hong, who heads the Chengdu Exhibition and Travel Group. Deng Hong was imprisoned in 2013, apparently for corruption, and has now been released and is back in the tourism business.[6] The InterContinental Hotels Group was contracted to manage 13 properties developed by Deng Hong’s company, including the Lhasa Paradise and the Jiuzhai Paradise in Ngaba (Chinese: Aba), the part of eastern Tibet where the wave of self-immolations by Tibetans began in 2009.

The boom in tourism in Lhasa today coexists with a security crackdown of unprecedented depth and scope, imposed following a wave of overwhelmingly peaceful protests that swept across the plateau in 2008, transforming the political landscape in Tibet.

GUTSA: SOME OF THE WORST ACCOUNTS OF TORTURE

Since 2008, the Chinese authorities have adopted a harsher approach to suppressing dissent and there has been a significant spike in the number of Tibetan political prisoners in Tibetan areas of the PRC.[7] There is also evidence that since 2008 torture has become more widespread and directed at a broader sector of society.[8] Although the PRC officially prohibits torture, it has become endemic in Tibet, a result both of a political emphasis on ensuring ‘stability’ and a culture of impunity among officials, paramilitary troops and security personnel.

The level of violence directed at Tibetan political prisoners in all detention facilities and prisons in Tibet is frequently extreme and has resulted in Tibetans being left with severe scars, including paralysis, the loss of limbs, organ damage, and serious psychological trauma.[9]

Many of the worst accounts of abuse and torture, including sexual violation, have emerged from Gutsa, a colloquial Tibetan name for the Lhasa Public Security Bureau detention center based on its location. Because it functions as the preliminary center for detention and interrogation, treatment is particularly brutal; one former prisoner said that this is because the authorities are often seeking admissions of ‘guilt’ or confessions, or extracting names of others involved in, for instance, a peaceful protest. Former prisoners have detailed torture sessions lasting for hours, detailing beatings with iron rods and tubes full of sand, among other forms of torture. Tibetans from across Lhasa’s seven counties who are detained following peaceful demonstrations, or for other reasons, are held here before being transferred to other prisons.

Another former political prisoner, now in exile, told the International Campaign for Tibet: “Gutsa is known to be worse than Drapchi [Prison] for cruel treatment of prisoners and torture.”

The number of Tibetans who passed through Gutsa and endured interrogation and torture spiked dramatically after protests broke out in Lhasa on March 10, 2008.[10] Given the unprecedented efforts made by the Chinese authorities to cover up the extent of the disappearances, detentions, torture and killings from March, 2008, onwards, it is not possible to give a comprehensive account of how many Tibetans have been detained at Gutsa since then. Restrictions on Tibetans who are released after serving terms in prison have intensified dramatically since 2008, and it is dangerous for them to speak even to their families about what they have endured while in detention.

An account by the Tibetan writer Tsering Woeser of the detentions after 2008 gives an idea of the scale of torture and imprisonment, and suggests the numbers of Tibetans who were held at Gutsa during this time. In a contemporaneous blog published on April 12, one month after the protests broke out, she wrote: “Over 800 people were detained inside a warehouse at the Lhasa Railway Station. Some were guarded by soldiers and some by the public security. Those who were kept under detention by the army suffered brutal physical torture, beating and are hungry. Those detained by the police fared better as they were served some food. Later, some of them were directly transferred to the Lhasa’s Gutsa detention center while some were transferred to prisons in Toelung Dechen County or Medrogongkar County before moving to the Gutsa detention center. As for the released, non Lhasa residents, were escorted back to the regions they came from. Then the detainees from Lhasa were released. Over 3,000 people have been arrested so far.”[11]

Tibetans who served long sentences after the March 2008 protests, either because of actual or alleged involvement, would have been most likely to be held in Gutsa Detention Center prior to being transferred to prisons. This includes a Tibetan called Dashar, from Sershul in Kardze (Chinese: Ganzi), the Tibetan area of Kham, who was imprisoned in Lhasa, charged with involvement in protests on March 10, 2008. He returned home in May, 2018.[12]

It is likely that the number of Tibetans detained in Gutsa also increased in 2012 in two occurrences of mass detention. The first involved a major and systematic operation by the Chinese authorities targeting and detaining Tibetans who returned from a major religious teaching, the Kalachakra, by the Dalai Lama in India in January, 2012. Around 7,000-8,000 Tibetan pilgrims attended the Kalachakra in Bodh Gaya and were monitored even while in India; upon return hundreds of them were detained and held for ‘re-education’. Gutsa was likely to have been used for this purpose.

One of the Tibetans held, a businessman, was severely tortured and beaten unconscious during his first 15 days in detention. His home was raided and DVDs of the Kalachakra teaching and photographs of the Dalai Lama were confiscated. An announcement posted outside Gutsa, according to a Tibetan source, stated that Jigme Topgyal, 55, had been sentenced to a two-year term of hard labor.[13]

In the second occurrence of mass detention that year, hundreds of Tibetans were detained following the self-immolation of two Tibetans outside the Jokhang Temple on May 27, 2012. An unknown number of Tibetans were held in detention centers in and around Lhasa, with many Tibetans from areas outside the TAR being expelled from the city.[14]

Prominent former political prisoner Jigme Gyatso, in his fifties, endured brutal torture during a period of detention in Gutsa of one year and one month, prior to serving a 17-year sentence in Drapchi and Chushur. During a brief meeting with the then U.N. Special Rapporteur on Torture, Dr Manfred Nowak, during his visit to Chushur Prison in 2005, Jigme Gyatso described his time in Gutsa as “the worst”. A friend of Jigme Gyatso’s who is now in exile told the International Campaign for Tibet: “Jigme Gyatso was severely tortured at Gutsa. He was held in a dark room, separate to about 17 other Tibetans who were detained at the same time. He was kept in heavy shackles.” The same Tibetan source said that during his detention at Gutsa, Jigme Gyatso managed to smuggle out a letter to a comrade saying that he was likely to receive a long prison sentence, but that he had no regrets. He referred to the 10th Panchen Lama’s long prison sentence and others who had served terms in jail for freedom, including the South African civil rights leader Nelson Mandela. When Gutsa officials discovered that he had sent this letter, Jigme Gyatso was beaten. Jigme Gyatso was released in 2013, suffering from multiple medical problems including weak eyesight, heart complications, kidney disorder and difficulty walking.[15]

In March 2012, 11 Tibetans were held in Lhasa – most likely in Gutsa – for having images of the Dalai Lama or songs about him on their mobile phones, according to Radio Free Asia (April 22, 2012). The report cited an official document dated April 6 (2012) and issued by the Lhasa PSB Brigade To Crack Down on Organized Crime.[16]

The testimony of one former prisoner, Tsering Samdup, who was held in Gutsa prior to a six-year prison sentence for unfurling a Tibetan flag in a demonstration in Lhasa in 1994, is typical of documented accounts of those held in Gutsa. He said: “In the first two months in Gutsa we were beaten and tortured terribly. We were put in separate cells from each other. I was in a small room with 11 other prisoners. There wasn’t enough space to stretch out our legs or lie down, so we had to stay crouched all day. Breakfast was a small bread roll and a black tea. There was no lunch. Dinner was another piece of bread with a spoonful of vegetables. Every day at 8am a guard would begin calling out names for interrogation. We were taken to different rooms to be individually interrogated and tortured.”[17]

GUTSA: SOME OF THE WORST ACCOUNTS OF TORTURE

Since 2008, the Chinese authorities have adopted a harsher approach to suppressing dissent and there has been a significant spike in the number of Tibetan political prisoners in Tibetan areas of the PRC.[7] There is also evidence that since 2008 torture has become more widespread and directed at a broader sector of society.[8] Although the PRC officially prohibits torture, it has become endemic in Tibet, a result both of a political emphasis on ensuring ‘stability’ and a culture of impunity among officials, paramilitary troops and security personnel.

The level of violence directed at Tibetan political prisoners in all detention facilities and prisons in Tibet is frequently extreme and has resulted in Tibetans being left with severe scars, including paralysis, the loss of limbs, organ damage, and serious psychological trauma.[9]

Many of the worst accounts of abuse and torture, including sexual violation, have emerged from Gutsa, a colloquial Tibetan name for the Lhasa Public Security Bureau detention center based on its location. Because it functions as the preliminary center for detention and interrogation, treatment is particularly brutal; one former prisoner said that this is because the authorities are often seeking admissions of ‘guilt’ or confessions, or extracting names of others involved in, for instance, a peaceful protest. Former prisoners have detailed torture sessions lasting for hours, detailing beatings with iron rods and tubes full of sand, among other forms of torture. Tibetans from across Lhasa’s seven counties who are detained following peaceful demonstrations, or for other reasons, are held here before being transferred to other prisons.

Another former political prisoner, now in exile, told the International Campaign for Tibet: “Gutsa is known to be worse than Drapchi [Prison] for cruel treatment of prisoners and torture.”

The number of Tibetans who passed through Gutsa and endured interrogation and torture spiked dramatically after protests broke out in Lhasa on March 10, 2008.[10] Given the unprecedented efforts made by the Chinese authorities to cover up the extent of the disappearances, detentions, torture and killings from March, 2008, onwards, it is not possible to give a comprehensive account of how many Tibetans have been detained at Gutsa since then. Restrictions on Tibetans who are released after serving terms in prison have intensified dramatically since 2008, and it is dangerous for them to speak even to their families about what they have endured while in detention.

An account by the Tibetan writer Tsering Woeser of the detentions after 2008 gives an idea of the scale of torture and imprisonment, and suggests the numbers of Tibetans who were held at Gutsa during this time. In a contemporaneous blog published on April 12, one month after the protests broke out, she wrote: “Over 800 people were detained inside a warehouse at the Lhasa Railway Station. Some were guarded by soldiers and some by the public security. Those who were kept under detention by the army suffered brutal physical torture, beating and are hungry. Those detained by the police fared better as they were served some food. Later, some of them were directly transferred to the Lhasa’s Gutsa detention center while some were transferred to prisons in Toelung Dechen County or Medrogongkar County before moving to the Gutsa detention center. As for the released, non Lhasa residents, were escorted back to the regions they came from. Then the detainees from Lhasa were released. Over 3,000 people have been arrested so far.”[11]

Tibetans who served long sentences after the March 2008 protests, either because of actual or alleged involvement, would have been most likely to be held in Gutsa Detention Center prior to being transferred to prisons. This includes a Tibetan called Dashar, from Sershul in Kardze (Chinese: Ganzi), the Tibetan area of Kham, who was imprisoned in Lhasa, charged with involvement in protests on March 10, 2008. He returned home in May, 2018.[12]

It is likely that the number of Tibetans detained in Gutsa also increased in 2012 in two occurrences of mass detention. The first involved a major and systematic operation by the Chinese authorities targeting and detaining Tibetans who returned from a major religious teaching, the Kalachakra, by the Dalai Lama in India in January, 2012. Around 7,000-8,000 Tibetan pilgrims attended the Kalachakra in Bodh Gaya and were monitored even while in India; upon return hundreds of them were detained and held for ‘re-education’. Gutsa was likely to have been used for this purpose.

One of the Tibetans held, a businessman, was severely tortured and beaten unconscious during his first 15 days in detention. His home was raided and DVDs of the Kalachakra teaching and photographs of the Dalai Lama were confiscated. An announcement posted outside Gutsa, according to a Tibetan source, stated that Jigme Topgyal, 55, had been sentenced to a two-year term of hard labor.[13]

In the second occurrence of mass detention that year, hundreds of Tibetans were detained following the self-immolation of two Tibetans outside the Jokhang Temple on May 27, 2012. An unknown number of Tibetans were held in detention centers in and around Lhasa, with many Tibetans from areas outside the TAR being expelled from the city.[14]

Prominent former political prisoner Jigme Gyatso, in his fifties, endured brutal torture during a period of detention in Gutsa of one year and one month, prior to serving a 17-year sentence in Drapchi and Chushur. During a brief meeting with the then U.N. Special Rapporteur on Torture, Dr Manfred Nowak, during his visit to Chushur Prison in 2005, Jigme Gyatso described his time in Gutsa as “the worst”. A friend of Jigme Gyatso’s who is now in exile told the International Campaign for Tibet: “Jigme Gyatso was severely tortured at Gutsa. He was held in a dark room, separate to about 17 other Tibetans who were detained at the same time. He was kept in heavy shackles.” The same Tibetan source said that during his detention at Gutsa, Jigme Gyatso managed to smuggle out a letter to a comrade saying that he was likely to receive a long prison sentence, but that he had no regrets. He referred to the 10th Panchen Lama’s long prison sentence and others who had served terms in jail for freedom, including the South African civil rights leader Nelson Mandela. When Gutsa officials discovered that he had sent this letter, Jigme Gyatso was beaten. Jigme Gyatso was released in 2013, suffering from multiple medical problems including weak eyesight, heart complications, kidney disorder and difficulty walking.[15]

In March 2012, 11 Tibetans were held in Lhasa – most likely in Gutsa – for having images of the Dalai Lama or songs about him on their mobile phones, according to Radio Free Asia (April 22, 2012). The report cited an official document dated April 6 (2012) and issued by the Lhasa PSB Brigade To Crack Down on Organized Crime.[16]

The testimony of one former prisoner, Tsering Samdup, who was held in Gutsa prior to a six-year prison sentence for unfurling a Tibetan flag in a demonstration in Lhasa in 1994, is typical of documented accounts of those held in Gutsa. He said: “In the first two months in Gutsa we were beaten and tortured terribly. We were put in separate cells from each other. I was in a small room with 11 other prisoners. There wasn’t enough space to stretch out our legs or lie down, so we had to stay crouched all day. Breakfast was a small bread roll and a black tea. There was no lunch. Dinner was another piece of bread with a spoonful of vegetables. Every day at 8am a guard would begin calling out names for interrogation. We were taken to different rooms to be individually interrogated and tortured.”[17]

EXPANSION AND MODERNIZATION OF PRISONS IN LHASA

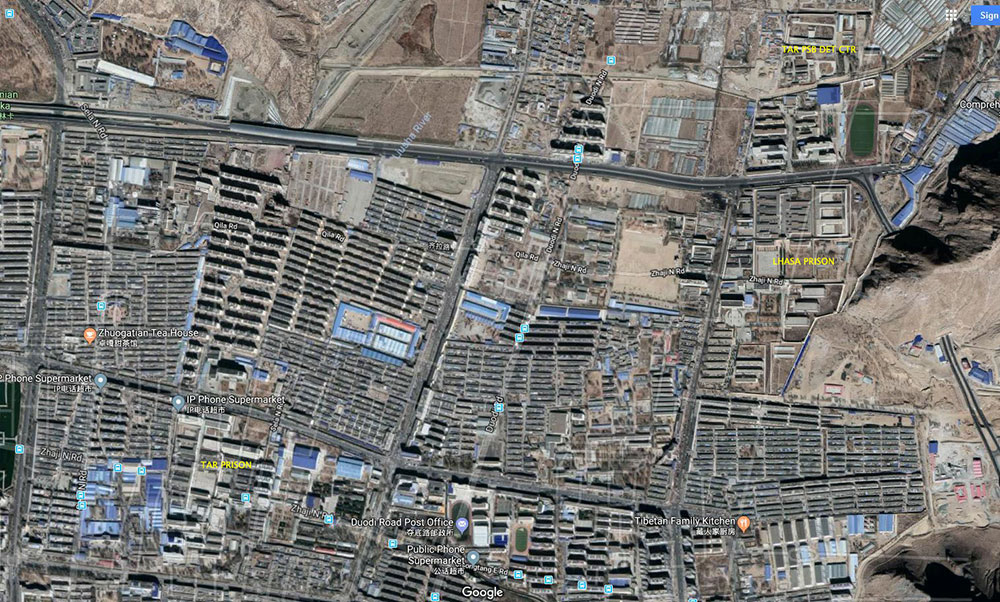

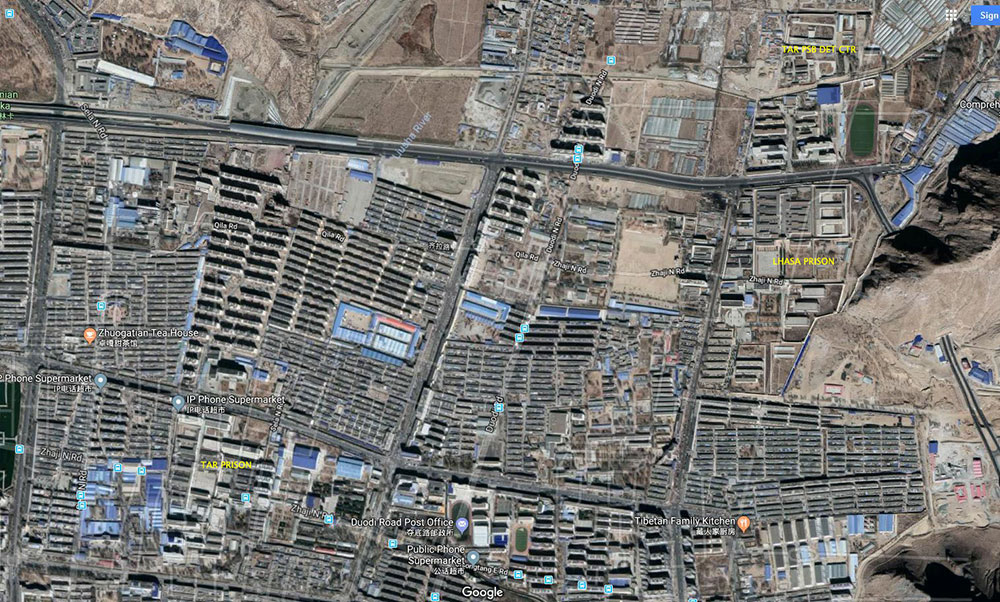

Recent satellite images of Lhasa reveal that key prison facilities in Lhasa have been dramatically modernized and increased in size, linked both to a larger population and a more systematic securitization in Tibet. This development is in the context of massive expansion and transformation of Lhasa, including infrastructure projects with roads intended to be wide enough to serve as runways for military planes in line with the Chinese government’s focus on security and militarization.[18]

Although the Chinese authorities seek to hide the existence of such extensive prison facilities in a city at the forefront of a push to attract tourists to the Tibetan plateau, the accompanying images obtained by the International Campaign for Tibet show the major facilities today, compared to earlier photos taken by expert observers. The contrasts are striking; the general locations have not changed but the perimeters are not the same. The newer structures are far more modern, with new buildings inside compounds, and appear to have greater capacity than the old facilities.

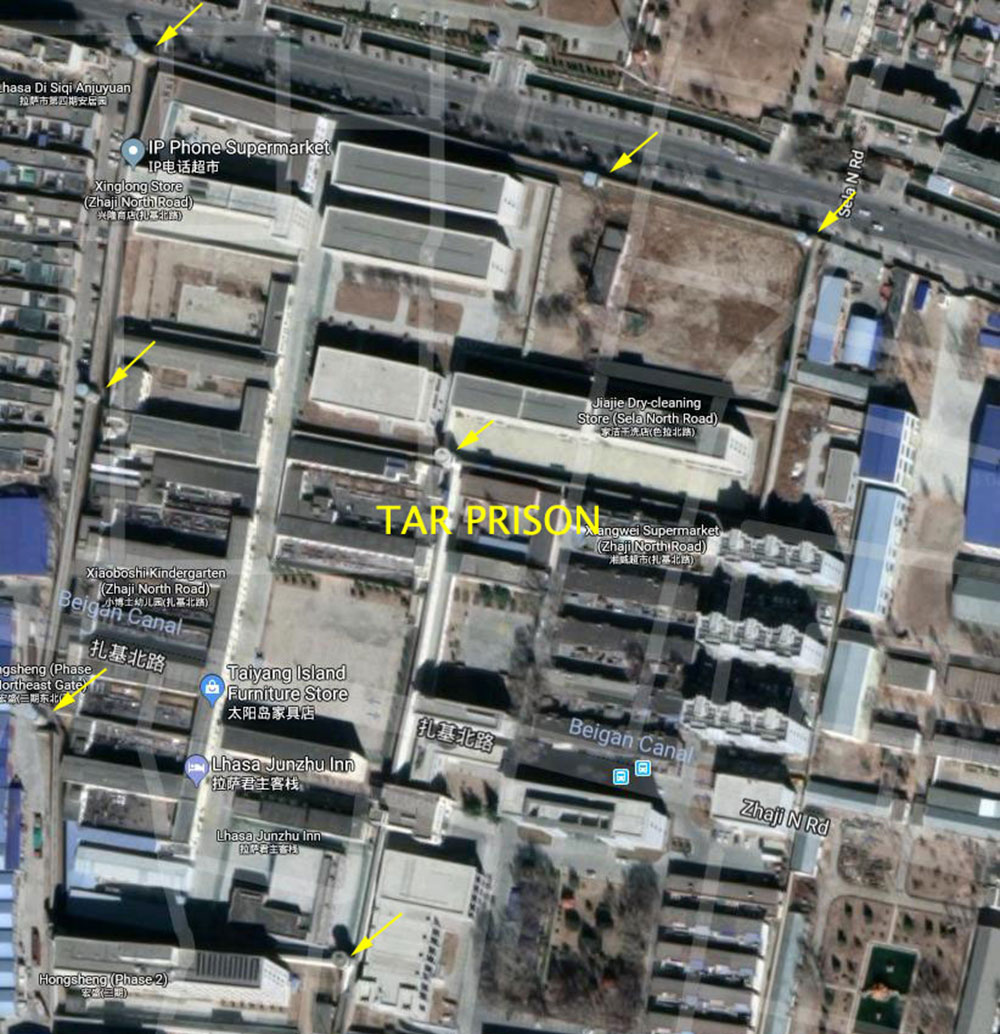

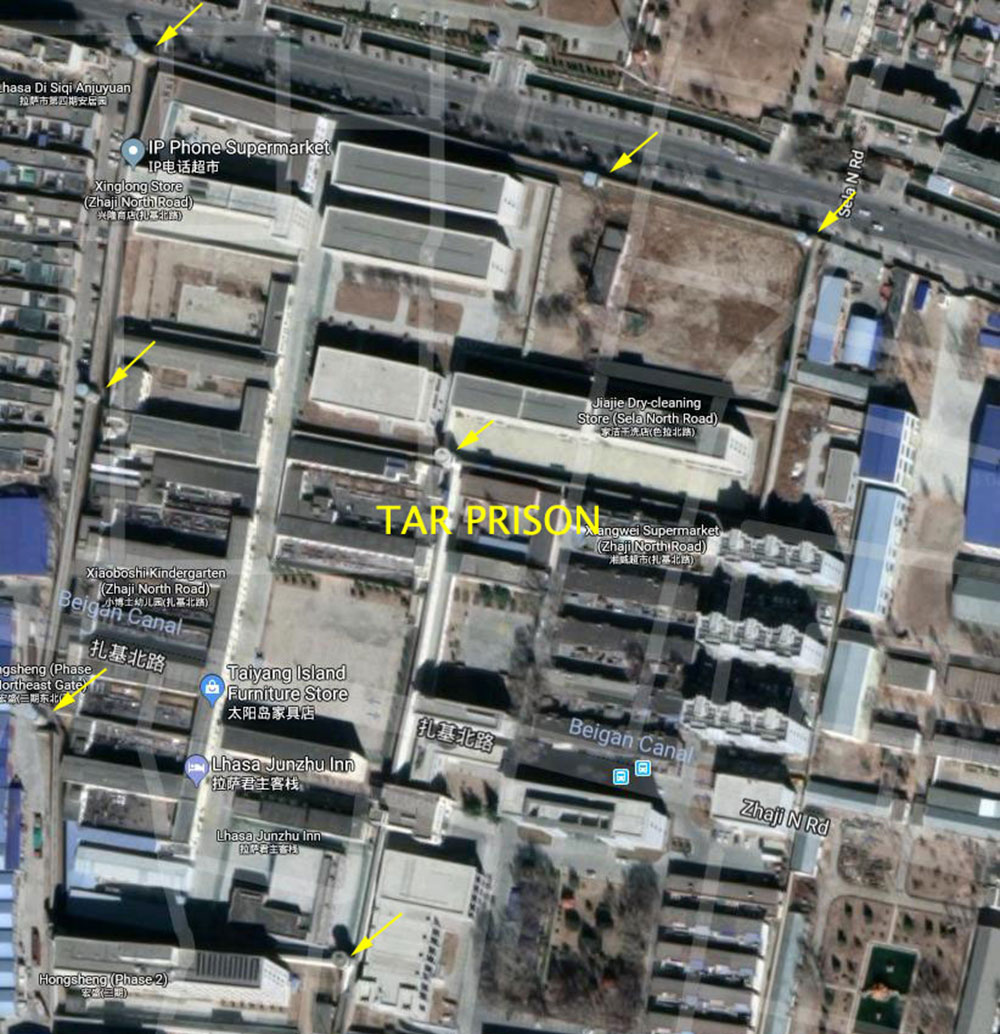

It is notable that none of the prison facilities or security installations viewed on satellite images in Lhasa are marked with their actual function. Part of the compound of Gutsa is tagged as a ‘telephone supermarket’ while Chushur (Chinese: Qushui) Prison is labeled as a teashop. It is not known whether this type of tagging may represent efforts to disguise or camouflage the detention facilities.

China allows no outside organizations to visit its prisons on a regular or systematic basis, and does not issue statistics on the number of prisoners. While it has been impossible for many years to know how many Tibetans have been charged with common crimes for what in reality was non-violent political activity, since 2008, when the crackdown became more intense, the system has become an impenetrable black box. Sometimes even close family members will not know whether their relatives sentenced to long prison terms are still alive or not, and even basic questions of their welfare can be impossible to ascertain.

The Chinese government maintains it holds no political prisoners, but this is because political offenses are not identified as such in Chinese law. Instead, nonviolent political activity inconsistent with official ideology can be labeled “subversion,” “endangering state security,” “plotting the overthrow of the state,” or merely “disturbing public order.”[19]

It took several decades for the Chinese to admit that they had more than one prison in the Tibet Autonomous Region. In 2004, the Chinese authorities were still admitting only to the existence of three prisons (meaning a facility for holding tried prisoners) in the Tibet Autonomous Region. Until Chushur Prison was opened in 2005, the three formally designated provincially ranked prisons in the TAR were Drapchi, Powo Tramo (Tibet Autonomous Region Prison Number Two) and Lhasa Prison (Utritru a Tibetanization of the Chinese wuzhidui, or “number five detachment”), at Sangyip several kilometres north-east of the Jokhang Temple in central Lhasa.[20] The International Campaign for Tibet has documented a number of deaths of Tibetan political prisoners following time served in Gutsa, Drapchi and Chushur Prison. In December, 2010, Yeshi Tenzin, who was accused of disseminating political leaflets, died after being released from a ten-year prison sentence. Yeshi Tenzin had attended a major religious ceremony led by the Dalai Lama in exile in India in early 2000, and upon his return he was accused of organizing the dissemination of leaflets deemed as ‘separatist’. He served his prison sentence in Tibet Autonomous Region Prison, known as Drapchi, and later in Chushur prison, also in Lhasa. Yeshi Tenzin died ten months following his release, on October 7, 2011, in hospital in Lhasa. Tibetan sources said that half of his body was paralyzed, and that he had been deprived of medical treatment despite enduring severe torture.[21]

Ngawang Jamphel (Ngawang Jamyang), a senior Tibetan Buddhist scholar monk died in custody in December, 2013. Ngawang Jampel, 45, was among three monks from Tarmoe monastery in Driru (Chinese: Biru), who ‘disappeared’ into detention on November 23, 2013 while on a visit to Lhasa. This followed a police raid on the monastery, which was then shut down, and paramilitary troops stationed there. Less than a month later, Ngawang Jampel, who had been healthy and robust, was dead, and Tibetan sources in contact with Tibetans in Driru said it was clear he had been beaten to death in custody. Ngawang Jampel had been one of the highest-ranking scholars at his monastery and had founded a Buddhist dialectics class for local people. He gave free teachings on Tibetan Buddhism and culture to lay people and monks, and was known for his skills in mediation in community disputes. It is not known whether he was held in Gutsa Detention Center or another detention facility in Lhasa.[22]

EXPANSION AND MODERNIZATION OF PRISONS IN LHASA

Recent satellite images of Lhasa reveal that key prison facilities in Lhasa have been dramatically modernized and increased in size, linked both to a larger population and a more systematic securitization in Tibet. This development is in the context of massive expansion and transformation of Lhasa, including infrastructure projects with roads intended to be wide enough to serve as runways for military planes in line with the Chinese government’s focus on security and militarization.[18]

Although the Chinese authorities seek to hide the existence of such extensive prison facilities in a city at the forefront of a push to attract tourists to the Tibetan plateau, the accompanying images obtained by the International Campaign for Tibet show the major facilities today, compared to earlier photos taken by expert observers. The contrasts are striking; the general locations have not changed but the perimeters are not the same. The newer structures are far more modern, with new buildings inside compounds, and appear to have greater capacity than the old facilities.

It is notable that none of the prison facilities or security installations viewed on satellite images in Lhasa are marked with their actual function. Part of the compound of Gutsa is tagged as a ‘telephone supermarket’ while Chushur (Chinese: Qushui) Prison is labeled as a teashop. It is not known whether this type of tagging may represent efforts to disguise or camouflage the detention facilities.

China allows no outside organizations to visit its prisons on a regular or systematic basis, and does not issue statistics on the number of prisoners. While it has been impossible for many years to know how many Tibetans have been charged with common crimes for what in reality was non-violent political activity, since 2008, when the crackdown became more intense, the system has become an impenetrable black box. Sometimes even close family members will not know whether their relatives sentenced to long prison terms are still alive or not, and even basic questions of their welfare can be impossible to ascertain.

The Chinese government maintains it holds no political prisoners, but this is because political offenses are not identified as such in Chinese law. Instead, nonviolent political activity inconsistent with official ideology can be labeled “subversion,” “endangering state security,” “plotting the overthrow of the state,” or merely “disturbing public order.”[19]

It took several decades for the Chinese to admit that they had more than one prison in the Tibet Autonomous Region. In 2004, the Chinese authorities were still admitting only to the existence of three prisons (meaning a facility for holding tried prisoners) in the Tibet Autonomous Region. Until Chushur Prison was opened in 2005, the three formally designated provincially ranked prisons in the TAR were Drapchi, Powo Tramo (Tibet Autonomous Region Prison Number Two) and Lhasa Prison (Utritru a Tibetanization of the Chinese wuzhidui, or “number five detachment”), at Sangyip several kilometres north-east of the Jokhang Temple in central Lhasa.[20] The International Campaign for Tibet has documented a number of deaths of Tibetan political prisoners following time served in Gutsa, Drapchi and Chushur Prison. In December, 2010, Yeshi Tenzin, who was accused of disseminating political leaflets, died after being released from a ten-year prison sentence. Yeshi Tenzin had attended a major religious ceremony led by the Dalai Lama in exile in India in early 2000, and upon his return he was accused of organizing the dissemination of leaflets deemed as ‘separatist’. He served his prison sentence in Tibet Autonomous Region Prison, known as Drapchi, and later in Chushur prison, also in Lhasa. Yeshi Tenzin died ten months following his release, on October 7, 2011, in hospital in Lhasa. Tibetan sources said that half of his body was paralyzed, and that he had been deprived of medical treatment despite enduring severe torture.[21]

Ngawang Jamphel (Ngawang Jamyang), a senior Tibetan Buddhist scholar monk died in custody in December, 2013. Ngawang Jampel, 45, was among three monks from Tarmoe monastery in Driru (Chinese: Biru), who ‘disappeared’ into detention on November 23, 2013 while on a visit to Lhasa. This followed a police raid on the monastery, which was then shut down, and paramilitary troops stationed there. Less than a month later, Ngawang Jampel, who had been healthy and robust, was dead, and Tibetan sources in contact with Tibetans in Driru said it was clear he had been beaten to death in custody. Ngawang Jampel had been one of the highest-ranking scholars at his monastery and had founded a Buddhist dialectics class for local people. He gave free teachings on Tibetan Buddhism and culture to lay people and monks, and was known for his skills in mediation in community disputes. It is not known whether he was held in Gutsa Detention Center or another detention facility in Lhasa.[22]

This image, taken in late 1993, shows Utritu, officially known as Lhasa Prison, and Sitru, Tibet Autonomous Region Public Security Bureau Detention Center. Sitru, a Tibetan version of ‘sizhidui’ or ‘Number Four unit’ is a Tibet Autonomous Region-level police detention center just north of Utritu (Lhasa Prison). It has been known for dealing with those thought to pose a risk to state security – as opposed to public security. According to a report by Steven D Marshall for the Tibet Information Network covering political imprisonment in Tibet from 1987-1998, “People held for investigation at Sitru are often suspected of having had contact with ‘foreigners’, especially Tibetans who live in exile, or have travelled abroad themselves, especially to India and Nepal, or are believed to have been involved with collecting or transferring information about human rights.” Sonam Drolkar, a lay nun whose political activism involved being interviewed for a television documentary by a foreign journalist in 1990, nearly died from six months of sustained torture during the ten months she was at Sitru. (Information from ‘Hostile Elements’, cited in main text of the report). Used with kind permission of the photographer.

This image, taken in late 1993, shows Utritu, officially known as Lhasa Prison, and Sitru, Tibet Autonomous Region Public Security Bureau Detention Center. Sitru, a Tibetan version of ‘sizhidui’ or ‘Number Four unit’ is a Tibet Autonomous Region-level police detention center just north of Utritu (Lhasa Prison). It has been known for dealing with those thought to pose a risk to state security – as opposed to public security. According to a report by Steven D Marshall for the Tibet Information Network covering political imprisonment in Tibet from 1987-1998, “People held for investigation at Sitru are often suspected of having had contact with ‘foreigners’, especially Tibetans who live in exile, or have travelled abroad themselves, especially to India and Nepal, or are believed to have been involved with collecting or transferring information about human rights.” Sonam Drolkar, a lay nun whose political activism involved being interviewed for a television documentary by a foreign journalist in 1990, nearly died from six months of sustained torture during the ten months she was at Sitru. (Information from ‘Hostile Elements’, cited in main text of the report). Used with kind permission of the photographer.

This image, taken in late 1993, shows what appears to be the full extent of the Utritu (Lhasa Prison) area. It was not high security like Drapchi Prison at that time. The image is marked up showing People’s Armed Police accommodation, main cell-blocks and living quarters. The residential areas near the main gate could have been used by families of prisoners. Image used with kind permission of the photographer.

This image, taken in late 1993, shows what appears to be the full extent of the Utritu (Lhasa Prison) area. It was not high security like Drapchi Prison at that time. The image is marked up showing People’s Armed Police accommodation, main cell-blocks and living quarters. The residential areas near the main gate could have been used by families of prisoners. Image used with kind permission of the photographer.

This recent image from Google Earth (2018) shows Drapchi (Tibet Autonomous Region) Prison, Utritu (Lhasa Prison) and Sitru (Tibet Autonomous Region Public Security Bureau Detention Center) in order to show their relative locations. Utritu, a Tibetanized form of the Chinese ‘wuzhidui’ or Number Five Unit, was completed by 1988 and is part of a group of prisons collectively known as Sangyip in north-east Lhasa. Utritu began to be referred to increasingly as Lhasa Prison. Utritu prison has not been a significant center for political imprisonment, although it has when deemed necessary been used to provide extra cells or solitary confinement facilities.

This recent image from Google Earth (2018) shows Drapchi (Tibet Autonomous Region) Prison, Utritu (Lhasa Prison) and Sitru (Tibet Autonomous Region Public Security Bureau Detention Center) in order to show their relative locations. Utritu, a Tibetanized form of the Chinese ‘wuzhidui’ or Number Five Unit, was completed by 1988 and is part of a group of prisons collectively known as Sangyip in north-east Lhasa. Utritu began to be referred to increasingly as Lhasa Prison. Utritu prison has not been a significant center for political imprisonment, although it has when deemed necessary been used to provide extra cells or solitary confinement facilities.

DRAPCHI (TIBET AUTONOMOUS REGION PRISON)

DRAPCHI (TIBET AUTONOMOUS REGION PRISON)

Drapchi, officially known as Tibet Autonomous Region Prison, is named after its location about a mile from the center of the city, around one kilometer south of Sera monastery and two kilometers north of the holy Jokhang Temple. Before the newer and modernized Chushur (Chinese: Qushui) Prison was built, Drapchi was the main place of detention for judicially sentenced political prisoners in the Tibet Autonomous Region. As with the Chushur image on the satellite photograph, it is not labeled as a prison and there are various tags for instance for a children’s nursery and furniture store inside the walls of the prison in the image. The image shows the modernization and expansion of the prison, as well as construction in its surrounding areas since the early 1990s, in contrast with the image from 1993. (Screenshots from Google Earth by ICT)

Drapchi, officially known as Tibet Autonomous Region Prison, is named after its location about a mile from the center of the city, around one kilometer south of Sera monastery and two kilometers north of the holy Jokhang Temple. Before the newer and modernized Chushur (Chinese: Qushui) Prison was built, Drapchi was the main place of detention for judicially sentenced political prisoners in the Tibet Autonomous Region. As with the Chushur image on the satellite photograph, it is not labeled as a prison and there are various tags for instance for a children’s nursery and furniture store inside the walls of the prison in the image. The image shows the modernization and expansion of the prison, as well as construction in its surrounding areas since the early 1990s, in contrast with the image from 1993. (Screenshots from Google Earth by ICT)

This image shows Drapchi (Tibet Autonomous Region Prison) in 1993, showing the greenhouses where prisoners labored, growing vegetables. These greenhouses were later dismantled and the area taken up by new prison buildings inside the compound. A former political prisoner at Drapchi told the International Campaign for Tibet that when he was in prison in the late 1980s, he and other prisoners had been compelled to dig up trees and vegetation in order for the greenhouses to be built. He said that the remains of numerous bodies were in the earth below Drapchi, from the killings in Lhasa during the uprising in March, 1959. Image used with kind permission of the photographer.

This image shows Drapchi (Tibet Autonomous Region Prison) in 1993, showing the greenhouses where prisoners labored, growing vegetables. These greenhouses were later dismantled and the area taken up by new prison buildings inside the compound. A former political prisoner at Drapchi told the International Campaign for Tibet that when he was in prison in the late 1980s, he and other prisoners had been compelled to dig up trees and vegetation in order for the greenhouses to be built. He said that the remains of numerous bodies were in the earth below Drapchi, from the killings in Lhasa during the uprising in March, 1959. Image used with kind permission of the photographer.

Over the years the predominance of reports from Drapchi Prison in the late 1980s and early ‘90s owed much to its relative accessibility in Lhasa. Following protests at Drapchi in May, 1998, during the visit of a European Union delegation and resulting in the deaths of a number of prisoners, the authorities began to steadily reinforce measures to prevent information from going beyond the prison walls by tightening security on prisoners, visitors and staff.[23] Since the protests of 2008, the prison system is even more impenetrable, with released prisoners kept under tight surveillance and prevented from speaking about their ordeal, or about the welfare of other prisoners, to the outside world – and often even to close relatives.

Over the years the predominance of reports from Drapchi Prison in the late 1980s and early ‘90s owed much to its relative accessibility in Lhasa. Following protests at Drapchi in May, 1998, during the visit of a European Union delegation and resulting in the deaths of a number of prisoners, the authorities began to steadily reinforce measures to prevent information from going beyond the prison walls by tightening security on prisoners, visitors and staff.[23] Since the protests of 2008, the prison system is even more impenetrable, with released prisoners kept under tight surveillance and prevented from speaking about their ordeal, or about the welfare of other prisoners, to the outside world – and often even to close relatives.

Drapchi prison, as seen on Baidu Street View, August, 2018. (Screenshot: ICT)

Drapchi prison, as seen on Baidu Street View, August, 2018. (Screenshot: ICT)

CHUSHUR (QUSHUI) PRISON

CHUSHUR (QUSHUI) PRISON

Chushur (Qushui) Prison is a high-security facility that opened in 2005, on the road out of Lhasa to Shigatse (Chinese: Rigaze). Tibetans who are serving long sentences following the 2008 protests are likely to be held in Chushur, but given the extent to which the Chinese authorities block information about such issues and the dangers for family and friends of long-term political inmates, it is not possible to confirm their identities. While once a rural area, this satellite image shows that the area around it is now much more built-up, like the rest of Lhasa. The prison is not labeled on this GoogleEarth image, and tags of the Agricultural Bank of China and others can be seen superimposed on the image. It is not known if this is an attempt to disguise or camouflage its function as a prison.

Chushur (Qushui) Prison is a high-security facility that opened in 2005, on the road out of Lhasa to Shigatse (Chinese: Rigaze). Tibetans who are serving long sentences following the 2008 protests are likely to be held in Chushur, but given the extent to which the Chinese authorities block information about such issues and the dangers for family and friends of long-term political inmates, it is not possible to confirm their identities. While once a rural area, this satellite image shows that the area around it is now much more built-up, like the rest of Lhasa. The prison is not labeled on this GoogleEarth image, and tags of the Agricultural Bank of China and others can be seen superimposed on the image. It is not known if this is an attempt to disguise or camouflage its function as a prison.

At the end of 2005, the UN’s then Special Rapporteur on Torture, Dr Manfred Nowak, became the first official international observer to visit Chushur Prison south-west of Lhasa following its opening in April, 2005. The prison, on the site of a detention facility that had been there since the 1960s, is in an area south-west of Lhasa in Chushur county, near Nyethang (Chinese: Niedang), off the road leading south from Lhasa towards Shigatse. While once a rural area, it is now much more built-up, like the rest of Lhasa. Dr Nowak noted that in this prison as well as others he visited in Lhasa there was: “a palpable level of fear and censorship”.[24]

A former political prisoner who is familiar with Chushur told the International Campaign for Tibet: “On the outside the prison looks very modern and many of the facilities are new. But inside it is very tough and hard for prisoners, even compared to Drapchi prison.” A Tibetan source who has visited the prison reported that many prisoners are held there in solitary confinement, specifically in ‘punishment’ (solitary) cells (sometimes known as ‘dark cells’ due to the lack of natural light and poor conditions). The transfer of political prisoners to the new prison facility in 2005 may have been an indication of the authorities’ continuing concern to keep political prisoners away from other prisoners in established detention facilities in Lhasa, as well as issues of space at Drapchi (Tibet Autonomous Region Prison).

The same former political prisoner, who is now in exile, said: “In Drapchi you can see the sky and sometimes the mountains from the cells. But in the new prison there are smaller windows that are higher up, and the cells are more oppressive. It is in a more remote area, which I think is to keep the political prisoners far from Lhasa and other prisoners, so that no one can hear their voices.”[25] The former prisoner said at the time of its opening that levels of surveillance in the new prison are even higher than at Drapchi, consistent with its modernity. Some of these changes are likely to have been made at Drapchi and other detention facilities in Lhasa.

Political prisoners charged after the March 2008 protests may now be being held under tight security at Chushur Prison. For instance, a decade on, there is still virtually no information about the welfare of a group of Tibetan intellectuals imprisoned in 2008 and sentenced to long prison terms, probably at Chushur. Migmar Dhondup, a Tibetan passionate about Tibetan culture and nature conservation, was sentenced to 14 years in prison in 2008, while Wangdu, who worked for an international public health NGO, was sentenced to life. Around the end of February 2012, eyewitnesses saw Wangdue in a solitary room at the Lhasa People’s Liberation Army hospital guarded by three police officers. One of his hands was apparently broken and he had one side of his head shaven, said eyewitnesses, adding these injuries point to the beatings Wangdue must have suffered in prison. The police officers monitoring Wangdue’s treatment at the army hospital kept strict watch over Wangdue’s movements and no one was allowed to meet him.[26]

Yeshe Choedron, a Tibetan woman, was sentenced to 15 years for ‘espionage’ at this same period.[27]

Tenzin Choedak, a 33-year old young NGO worker, died on March 19, 2014, less than six years into his 15-year jail term and following severe torture in Chushur Prison, and probably also in initial detention. Tenzin Choedak, also known as Tenchoe, aged 33, did not recover from injuries sustained while in police custody following his arrest for involvement in protests against Chinese rule in Lhasa in March, 2008, according to the India-based NGO Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy.[28]

Quoting a local eyewitness cited by TCHRD, Tenchoe was taken to hospital just before his death with his hands and legs heavily shackled. “He was almost unrecognizable,” said the source. “His physical condition had deteriorated and he had a brain injury in addition to vomiting blood.” The authorities sought to treat him in three hospitals, but when his condition continued to worsen, released him to the care of his family. He died two days later at the Mentsikhang, the tradition Tibetan medical institute in Lhasa, just hours after his family took him there.

Tenzin Choedak, who was born in Lhasa, escaped into exile as a child and was educated at Tibetan Children’s Village school in India for a few years. In 2005 he returned to Lhasa, and joined a European NGO affiliated to the Red Cross. Tenchoe was arrested in April, 2008, accusing him of being one of the ringleaders of the March protests, and he was sentenced to 15 years in prison, according to the Tibetan Center for Human Rights and Democracy.

At the end of 2005, the UN’s then Special Rapporteur on Torture, Dr Manfred Nowak, became the first official international observer to visit Chushur Prison south-west of Lhasa following its opening in April, 2005. The prison, on the site of a detention facility that had been there since the 1960s, is in an area south-west of Lhasa in Chushur county, near Nyethang (Chinese: Niedang), off the road leading south from Lhasa towards Shigatse. While once a rural area, it is now much more built-up, like the rest of Lhasa. Dr Nowak noted that in this prison as well as others he visited in Lhasa there was: “a palpable level of fear and censorship”.[24]

A former political prisoner who is familiar with Chushur told the International Campaign for Tibet: “On the outside the prison looks very modern and many of the facilities are new. But inside it is very tough and hard for prisoners, even compared to Drapchi prison.” A Tibetan source who has visited the prison reported that many prisoners are held there in solitary confinement, specifically in ‘punishment’ (solitary) cells (sometimes known as ‘dark cells’ due to the lack of natural light and poor conditions). The transfer of political prisoners to the new prison facility in 2005 may have been an indication of the authorities’ continuing concern to keep political prisoners away from other prisoners in established detention facilities in Lhasa, as well as issues of space at Drapchi (Tibet Autonomous Region Prison).

The same former political prisoner, who is now in exile, said: “In Drapchi you can see the sky and sometimes the mountains from the cells. But in the new prison there are smaller windows that are higher up, and the cells are more oppressive. It is in a more remote area, which I think is to keep the political prisoners far from Lhasa and other prisoners, so that no one can hear their voices.”[25] The former prisoner said at the time of its opening that levels of surveillance in the new prison are even higher than at Drapchi, consistent with its modernity. Some of these changes are likely to have been made at Drapchi and other detention facilities in Lhasa.

Political prisoners charged after the March 2008 protests may now be being held under tight security at Chushur Prison. For instance, a decade on, there is still virtually no information about the welfare of a group of Tibetan intellectuals imprisoned in 2008 and sentenced to long prison terms, probably at Chushur. Migmar Dhondup, a Tibetan passionate about Tibetan culture and nature conservation, was sentenced to 14 years in prison in 2008, while Wangdu, who worked for an international public health NGO, was sentenced to life. Around the end of February 2012, eyewitnesses saw Wangdue in a solitary room at the Lhasa People’s Liberation Army hospital guarded by three police officers. One of his hands was apparently broken and he had one side of his head shaven, said eyewitnesses, adding these injuries point to the beatings Wangdue must have suffered in prison. The police officers monitoring Wangdue’s treatment at the army hospital kept strict watch over Wangdue’s movements and no one was allowed to meet him.[26]

Yeshe Choedron, a Tibetan woman, was sentenced to 15 years for ‘espionage’ at this same period.[27]

Tenzin Choedak, a 33-year old young NGO worker, died on March 19, 2014, less than six years into his 15-year jail term and following severe torture in Chushur Prison, and probably also in initial detention. Tenzin Choedak, also known as Tenchoe, aged 33, did not recover from injuries sustained while in police custody following his arrest for involvement in protests against Chinese rule in Lhasa in March, 2008, according to the India-based NGO Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy.[28]

Quoting a local eyewitness cited by TCHRD, Tenchoe was taken to hospital just before his death with his hands and legs heavily shackled. “He was almost unrecognizable,” said the source. “His physical condition had deteriorated and he had a brain injury in addition to vomiting blood.” The authorities sought to treat him in three hospitals, but when his condition continued to worsen, released him to the care of his family. He died two days later at the Mentsikhang, the tradition Tibetan medical institute in Lhasa, just hours after his family took him there.

Tenzin Choedak, who was born in Lhasa, escaped into exile as a child and was educated at Tibetan Children’s Village school in India for a few years. In 2005 he returned to Lhasa, and joined a European NGO affiliated to the Red Cross. Tenchoe was arrested in April, 2008, accusing him of being one of the ringleaders of the March protests, and he was sentenced to 15 years in prison, according to the Tibetan Center for Human Rights and Democracy.

Chushur prison, as seen on Baidu Street View (August, 2018). (Screenshot: ICT)

Chushur prison, as seen on Baidu Street View (August, 2018). (Screenshot: ICT)

CHANGES AT TRISAM DETENTION FACILITY

CHANGES AT TRISAM DETENTION FACILITY

This satellite image, taken recently in 2018, shows the former area of Trisam ‘re-education through labor’ (RTL, or laojiao) facility in Lhasa. It shows there are new walls but no watch-towers are visible. While it could not be confirmed, expert observers believe that although China closed down the RTL system, the authorities may still be using Trisam possibly as a compulsory education center. Compared to the image taken in 1993, it shows the dramatic changes in urbanisation in the surrounding areas. In comparison, it also shows the modernization of the former camp, with new blocks in the three areas Trisam occupied.

This satellite image, taken recently in 2018, shows the former area of Trisam ‘re-education through labor’ (RTL, or laojiao) facility in Lhasa. It shows there are new walls but no watch-towers are visible. While it could not be confirmed, expert observers believe that although China closed down the RTL system, the authorities may still be using Trisam possibly as a compulsory education center. Compared to the image taken in 1993, it shows the dramatic changes in urbanisation in the surrounding areas. In comparison, it also shows the modernization of the former camp, with new blocks in the three areas Trisam occupied.

This image of Trisam taken in 1993, with two watch-towers visible, can be compared to the modernization of the buildings and expanded area in the footprint of Trisam today. Image used with kind permission of the photographer.

This image of Trisam taken in 1993, with two watch-towers visible, can be compared to the modernization of the buildings and expanded area in the footprint of Trisam today. Image used with kind permission of the photographer.

The satellite images examined by the International Campaign for Tibet indicate that the Trisam ‘re-education through labor’ (RTL, or laojiao) facility may still be used by the authorities, although guard towers cannot be observed on the building, as with the official detention facilities. While China moved to abolish the RTL system in 2013, it still uses a network of ‘black jails’, psychiatric institutions or ‘Legal Education’ centers in what has become under China’s leader Xi Jinping the most sweeping and systematic crackdown on civil society in a generation across the PRC.

Trisam, known colloquially after a bridge nearby, is situated around 14 kilometers west of Lhasa city center in the western suburbs, just inside Toelung Dechen (Chinese: Duilong Deqing) county. Under the RTL system, detainees could be imprisoned there by administrative order for up to three years, carrying out a variety of labor tasks ranging from tending vegetables and emptying septic pits to cutting stone blocks or performing construction labor. Four Trisam prisoners are known to have died between 1987-1998 as a consequence of abuse at Trisam and earlier places of detention, three of them within three months after release and one while in custody. One of them, Sherab Ngawang, was a nun aged 12 when she was detained for demonstrating.[29]

The satellite images show a building within Trisam, the Tibet Autonomous Region Reform Through Labor facility footprint that is enclosed by walls and seems to have a controlled entry point. While it may not be an official detention facility, and does not have guard towers, experienced observers conclude that it could be used as some sort of ‘re-education’ or compulsory education center.

Such a facility could be used to detain and ‘disappear’ Tibetans during political campaigns for temporary periods. For instance, hundreds of Tibetans were detained for ‘re-education’ after returning from teachings by the Dalai Lama in India in 2012, in a highly systematic operation that involved keeping Tibetans under surveillance in India as well as tracking their return.[30] Given the numbers of those detained, with some sources referring to around 500, several different facilities were apparently used to hold Tibetans, with reports of a school and army camp being used, and Trisam may have been one of those used.

A relative of a Tibetan who self-immolated in Lhasa in 2012 was apparently sentenced to two years at Trisam following his detention on October 6, 2012, according to Tibetan media. Tibetan males Dorje, Tashi Choewang, and Sonam were detained two days after Tashi Choewang’s uncle, Gudrub, committed self-immolation, with Dorje ordered to serve two years’ reeducation through labor (RTL). Sources implied a link between Dorje’s punishment and Gudrub’s self-immolation, but did not provide details.[31]

Also since around 2012, the Chinese authorities have been compelling monks and nuns studying in Tibetan areas of Qinghai and Sichuan, for instance at the influential monastic institute of Larung Gar, to return to their home areas in the Tibet Autonomous Region as part of oppressive policies controlling religious activity. Upon return, monks and nuns have been held in ‘re-education’ centers for weeks and months – effectively a new version of the ‘Re-education through labor’ system that China states it has now abolished. Facilities would also be required for these detainees.

A Tibetan monk who spent four months in a ‘re-education center’ in Sog (Chinese: Suo) County, Nagchu Prefecture in the Tibet Autonomous Region gave an account to the Tibetan Center for Human Rights and Democracy of torture and sexual abuse in these centers. “Sometimes during evening classes, we were subjected to ‘struggle sessions’ reminiscent of 1959 and sometimes we had to participate in military drills,” the monk wrote in a letter obtained by TCHRD. “I always felt compassion for the older monks and nuns. In addition to not understanding Chinese language, they were physically weak due to which they always became the target of beatings at the hands of the detention officers […] During one of the drills, all nuns collapsed, losing consciousness. In no time, the officers rushed forward to take the nuns inside. Who knows what else they did to the nuns? But I have heard about some officers lying in the nuns’ bedroom pressing unconscious nuns underneath.”[32]

The satellite images examined by the International Campaign for Tibet indicate that the Trisam ‘re-education through labor’ (RTL, or laojiao) facility may still be used by the authorities, although guard towers cannot be observed on the building, as with the official detention facilities. While China moved to abolish the RTL system in 2013, it still uses a network of ‘black jails’, psychiatric institutions or ‘Legal Education’ centers in what has become under China’s leader Xi Jinping the most sweeping and systematic crackdown on civil society in a generation across the PRC.

Trisam, known colloquially after a bridge nearby, is situated around 14 kilometers west of Lhasa city center in the western suburbs, just inside Toelung Dechen (Chinese: Duilong Deqing) county. Under the RTL system, detainees could be imprisoned there by administrative order for up to three years, carrying out a variety of labor tasks ranging from tending vegetables and emptying septic pits to cutting stone blocks or performing construction labor. Four Trisam prisoners are known to have died between 1987-1998 as a consequence of abuse at Trisam and earlier places of detention, three of them within three months after release and one while in custody. One of them, Sherab Ngawang, was a nun aged 12 when she was detained for demonstrating.[29]

The satellite images show a building within Trisam, the Tibet Autonomous Region Reform Through Labor facility footprint that is enclosed by walls and seems to have a controlled entry point. While it may not be an official detention facility, and does not have guard towers, experienced observers conclude that it could be used as some sort of ‘re-education’ or compulsory education center.

Such a facility could be used to detain and ‘disappear’ Tibetans during political campaigns for temporary periods. For instance, hundreds of Tibetans were detained for ‘re-education’ after returning from teachings by the Dalai Lama in India in 2012, in a highly systematic operation that involved keeping Tibetans under surveillance in India as well as tracking their return.[30] Given the numbers of those detained, with some sources referring to around 500, several different facilities were apparently used to hold Tibetans, with reports of a school and army camp being used, and Trisam may have been one of those used.

A relative of a Tibetan who self-immolated in Lhasa in 2012 was apparently sentenced to two years at Trisam following his detention on October 6, 2012, according to Tibetan media. Tibetan males Dorje, Tashi Choewang, and Sonam were detained two days after Tashi Choewang’s uncle, Gudrub, committed self-immolation, with Dorje ordered to serve two years’ reeducation through labor (RTL). Sources implied a link between Dorje’s punishment and Gudrub’s self-immolation, but did not provide details.[31]

Also since around 2012, the Chinese authorities have been compelling monks and nuns studying in Tibetan areas of Qinghai and Sichuan, for instance at the influential monastic institute of Larung Gar, to return to their home areas in the Tibet Autonomous Region as part of oppressive policies controlling religious activity. Upon return, monks and nuns have been held in ‘re-education’ centers for weeks and months – effectively a new version of the ‘Re-education through labor’ system that China states it has now abolished. Facilities would also be required for these detainees.

A Tibetan monk who spent four months in a ‘re-education center’ in Sog (Chinese: Suo) County, Nagchu Prefecture in the Tibet Autonomous Region gave an account to the Tibetan Center for Human Rights and Democracy of torture and sexual abuse in these centers. “Sometimes during evening classes, we were subjected to ‘struggle sessions’ reminiscent of 1959 and sometimes we had to participate in military drills,” the monk wrote in a letter obtained by TCHRD. “I always felt compassion for the older monks and nuns. In addition to not understanding Chinese language, they were physically weak due to which they always became the target of beatings at the hands of the detention officers […] During one of the drills, all nuns collapsed, losing consciousness. In no time, the officers rushed forward to take the nuns inside. Who knows what else they did to the nuns? But I have heard about some officers lying in the nuns’ bedroom pressing unconscious nuns underneath.”[32]

A SECURITY DRAGNET: THE GRASS ROOTS UNDERPINNING OF THE SECURITY STATE

A SECURITY DRAGNET: THE GRASS ROOTS UNDERPINNING OF THE SECURITY STATE

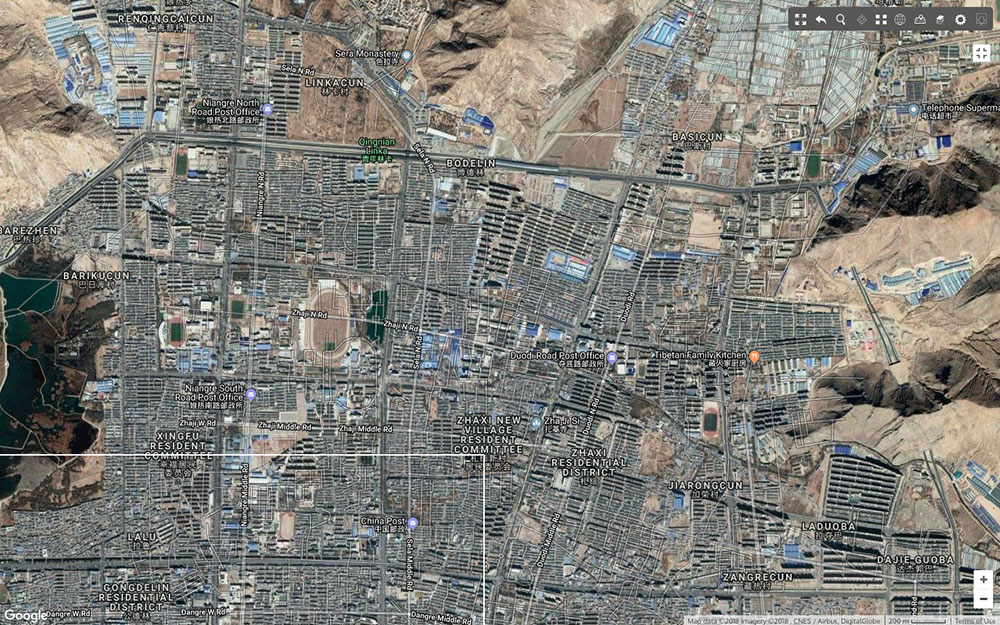

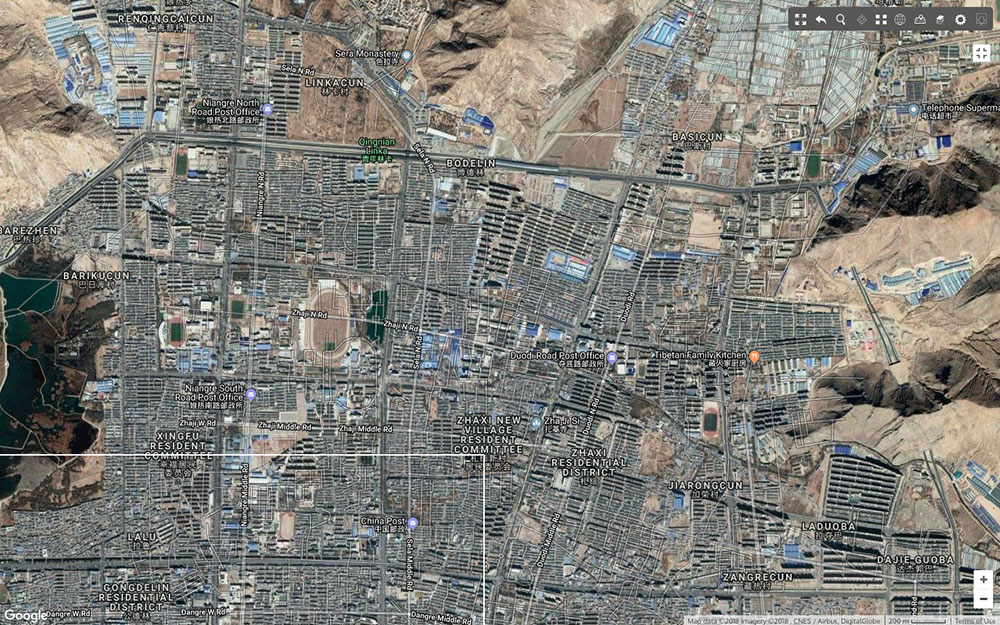

This satellite image obtained by the International Campaign for Tibet showing Lhasa a few months ago shows numerous ‘Residents Committees’, which despite the anodyne title, act as an integral element of the machinery of enforced compliance with Party policy.

This satellite image obtained by the International Campaign for Tibet showing Lhasa a few months ago shows numerous ‘Residents Committees’, which despite the anodyne title, act as an integral element of the machinery of enforced compliance with Party policy.

Satellite images of Lhasa reveal numerous buildings labeled as ‘Neighborhood Committees’, which, despite the anodyne title, act as an integral element of the machinery of enforced compliance with Party policy, bringing security operations to the grass-roots level to fight the influence of what the Chinese authorities term the “Dalai clique”.

Neighborhood or residents’ committees have the primary purpose of gathering and storing information, to be used in a centrally-coordinated system, as well as special tracking of individuals who belong to “special groups”. This includes political prisoners, nuns, and monks who are not resident in a monastery or nunnery, former monks and nuns who have been expelled from their institutions, Tibetans who have returned from the exile community in India, those under suspicion for loyalty to the Dalai Lama, and people involved in earlier protests. Tibetans who have returned from India, termed as “returning people”, indicates the particular suspicion of those who are perceived to have come under the influence of the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan exile diaspora.[33]

Within this systematic strategy, imposed in the TAR by former Party Secretary Chen Quanguo, now in charge of mass detentions and oppressive measures on an unprecedented scale in Xinjiang,[34] ‘neighborhood committees’ are an integral element of the ‘grid management’ system of more comprehensive control and surveillance which was introduced into urban parts of the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) to form “nets in the sky and traps on the ground”.[35] ‘Residents committees’ can be seen across all areas of Lhasa in the satellite image, and unlike the prisons,[36] are marked as such.

The emphasis on hyper-securitization was highlighted at a Tourism and Culture Expo in Lhasa last month.[37] Although China promotes Tibet as being open to the world, under systematic new policies, unfettered access to Tibet has been blocked by the PRC in order to ensure absolute compliance with the ruling Communist Party’s policies and to dominate the global narrative on Tibet.[38] Security concerns are paramount, indicated by the language by TAR governor Che Dalha (Chinese: Qi Zhala) at the opening of the Expo, characterizing Tibet as “an important national security barrier”.[39] Ultimately tourism is subordinate to such strategic concerns, as indicated by the complete closure of the TAR to foreign visitors for around a month each year in March, the time of the anniversary of the March Uprising in 1959 and the protests in 2008.

The system of ‘grid management’ was first tested in Beijing in 2004 before being rolled out in Tibet under the leadership of hardline Party Secretary Chen Quanguo in 2011. Chen told officials in Tibet that ‘grid management’ was about “putting a dragnet into place to maintain stability.”[40] It involves human mobilization in neighborhood committees and other groups combined with high tech surveillance, and is based on breaking each urban area down into very small units, enabling the authorities to identify anything unusual, target individuals, and prevent the spread of information, ideas or actions that may be perceived to counter Party policy or diktats. It emerges from the nationwide “social stability maintenance” (Chinese: weiwen) policy drive, referring to the crushing of any dissent and ensuring allegiance to the CCP authorities in order for the authorities to pursue their strategic and economic objectives on the plateau without impediment.

When Chen was transferred to Xinjiang in August 2016, he supervised the installation of the same complex network of surveillance and control, which became the basis of the current unprecedented crisis in which more than a million Uyghurs have been detained in massive camps. Xinjiang has turned into “something resembling a massive internment camp, shrouded in secrecy, a sort of no-rights zone,” where Chinese authorities are seeking to “reeducate” its Muslim minorities, according to a United Nations panel, the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination in Geneva, in August.[41]

Linked to Party Secretary Chen’s tenure, the International Campaign for Tibet has tracked close collaboration between security officials in both the TAR and Xinjiang. In November, 2016, current TAR Party Secretary Wu Yingjie said that the Xinjiang authorities had “actively assisted” “social stability work” – a political phrase referring to enforcement of compliance to CCP policies – in Tibet for a long time, and that now this would be strengthened, with a particular emphasis on “safeguarding border security”.[42]

Satellite images of Lhasa reveal numerous buildings labeled as ‘Neighborhood Committees’, which, despite the anodyne title, act as an integral element of the machinery of enforced compliance with Party policy, bringing security operations to the grass-roots level to fight the influence of what the Chinese authorities term the “Dalai clique”.