The Communist Party of China has in recent years resorted to one of the classic tools of its “Who are our enemies?” Who are our friends?” strategy in attempting to contain the flourishing of the Tibetan tradition of Buddhism in mainland China and the Chinese diaspora. The International Campaign for Tibet has learned from reliable sources that the party now mandates that Tibetan Buddhism can only spread in Tibet and Chinese Buddhism can only spread in China. Han Chinese Buddhists practicing Tibetan Buddhism are told to either convert to Chinese Buddhism or return to a layman’s life. The party’s current strategy, although seemingly contradictory to the official stance, aims to curb the influence of the Tibetan tradition of Buddhism and the Tibetan religious teachers in the mainland Han Chinese Buddhist community. Party orders issued in mid-2019 explicitly call to contain the spread of Tibetan Buddhism in mainland China.

The Communist Party of China has adopted a slew of measures to mitigate the spread of the Tibetan tradition of Buddhism in mainland China and the influence of Tibetan religious teachers in Chinese society. Amid the CCP’s growing measures is the latest effort to curb the practice of mainland China-based Han Chinese followers of Tibetan Buddhism at the renowned Serthar Larung Five Sciences Buddhist Academy (popularly known as Larung Gar) in Serthar (Chinese: Seda) County, Sichuan.

ICT has learned that the once-burgeoning Han Chinese practitioner population has trickled to a minuscule number at the academy in the wake of a campaign targeting Han Chinese practitioners that has been noticeable since mid-2019. The campaign has stepped up recently since November 2021, resulting in the bulk of the coercive separations of Chinese Buddhist practitioners from the academy.

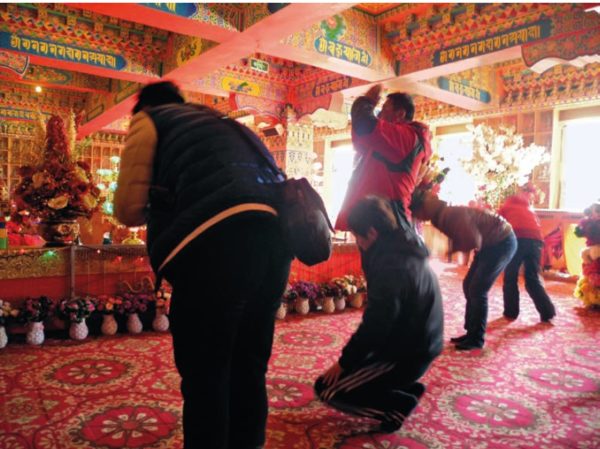

Han Chinese Buddhist devotees and practitioners at Larung Gar, February 2015. Photos by Sabina Ragaini. Reproduced from Ester Bianchi’s Teaching Tibetan Buddhism in Chinese on Behalf of Mañjuśrī. 2018.

Several measures are in place to ensure the removal of Chinese Buddhist practitioners from Larung Gar. Among these measures, the authorities have required the Chinese practitioners to return to their native hometowns in the mainland. Once they reach their respective hometowns, they are required to report and register their arrival at their local police station. To prevent them from returning to Larung Gar, they are also required to report to their local police station regularly. Beefed-up security checkpoints along the land route to Larung Gar also ensure they are not able to make their journey back to the academy. Night security have been put in place, and the trekking routes through the mountains to the academy are also manned by security personnel around the clock. Another measure is for the police stationed at the academy and the management committee to periodically search the monastic dwelling huts to evict the practitioners who have anyhow managed to re-enter despite the odds they were up against.

All these measures indicate that the removal of Han Chinese practitioners from Larung Gar Academy is firm and effective. The Han Chinese monastics who do not get enrollment at a monastery in their hometown, which is likely, would have to disrobe and lead a lay man’s life.

Lay women praying at Larung Gar. April 2015. Larung Gar Web-service. Reproduced from Ester Bianchi’s Teaching Tibetan Buddhism in Chinese on Behalf of Mañjuśrī. 2018.

In recent years, hundreds if not thousands of local societies and small groups of lay Han Chinese practitioners of Tibetan Buddhism have sprung up in mainland China, mainly in urban areas, to systematically study and exchange their knowledge of the Tibetan Buddhist corpus. ICT has learned that these societies and small groups are banned. The key people in these study groups have been routinely subjected to video interrogation and required to write pledge letters to the authorities, and some have even been coerced into becoming police informants.

Discriminatory Internet Religious Information Services Law

The Chinese Buddhist practitioners in mainland China and in the Chinese diaspora until recent months had access to their Tibetan teachers in the virtual space. Larung Gar was very successful in connecting with Chinese Buddhist practitioners by making the teachings accessible via the academy’s online webcasts. But that access most likely will be controlled significantly or even denied permanently with the coming into effect on March 1, 2022 of the Measures on the Administration of Internet Religious Information Services.[1] As a matter of fact, the authorities have already shut down the academy’s teachers webcasts since November 2021, five months prior to the law becoming effective. If they resume after the law comes into effect, the teachings most likely will be significantly controlled and politicized by government intervention per the permit requirement.

The National Religious Affairs Administration, Cyberspace Administration of China, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, Ministry of Public Security and Ministry of State Security jointly enacted the law. The law requires religious organizations or individuals that operate virtual religious teachings to apply for permits from the provincial religious affairs departments or higher. Article 6(1) of the law requires that the principal responsible person or the legal representative of a legal person organization and an unincorporated organization must be a resident of mainland China and a Chinese citizen. It is explicitly discriminatory against communities like Tibetans by limiting their religious freedom and the free expression of ideas of Tibetan Buddhism in the virtual space. Tibetans inhabiting peripheral Tibetan areas are directly discriminated against for their identity by the law.

According to the Chinese state media outlet Global Times, a subsidiary of the People’s Daily, “With the Permit, they could preach religious doctrines online that are conducive to social harmony and civilization, and guide religious people to be patriotic to the country and abide by the law, only via their own specialized internet websites, applications or forums that are approved by law. Participants shall register using their real names.”[2] In the eyes of the policymakers in Beijing, Tibetan Buddhist teachers do not fulfil their obligation of “guiding

religious people to be patriotic.” Patriotism in the Chinese context is defined as love for the motherland, socialism and the Communist Party.

Larung Chö Gar and the Chinese following

Larung Chö Gar (literally meaning Larung Religious Encampment), which has become a popular spiritual destination for Buddhist practitioners in mainland China, was founded by the late Khenpo Jigme Phuntsok (1933-2004), popularly known as Khenpo Jigphun, in 1980 to revive Buddhist scholarship and meditation in the wake of Mao Zedong’s turbulent Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). From its humble beginning at the desolate Larung valley, the academy gradually became a spiritual oasis for both Tibetan and Han Chinese Buddhist practitioners.[3] After the late Khenpo Jigphun’s visit to Mount Wutai (Wataishan) in China in 1987, Han Chinese devotees began following the late Khenpo back to his Larung Gar Academy in pursuit of a spiritual life.

Larung Gar’s location within Tibet.

With around 30 to 40 Han Chinese with semi-permanent residence at Larung Gar in 1991, the number grew to an informal quota of around 2,000 Han Chinese monks and nuns in residence among the academy’s roughly 5,000 practitioners (after the government’s ceiling to halve the earlier 10,000 practitioners) in recent years.[4] A practitioner spends between 12 to 14 years of study at the academy to be eligible to sit for the “Khenpo” or “Khenmo” scholarly title examination.

Equalizing the Genders

The academy is also remarkable for its female Khenmo (Abbess, scholarly title with the nominalizer “mo” for outstanding female practitioners equal to the male Khenpo title) degree program. The estimated 3,500 female practitioners at the academy significantly outnumber the male practitioners, estimated to be around 1,500.[5] As of 2018, around 200 female practitioners have been able to complete the rigorous Khenmo degree examination, according to Liang and Taylor of the University of Virginia. Out of the 200 practitioners, 104 were Tibetans.[6] They underwent the same curriculum as their male counterparts and fulfilled the same academic requirements to graduate for the scholarly title, thus shattering the once-popular perception that women lack the capacity for higher Buddhist education.

In both Tibetan and Chinese societies, women are constrained by tradition and customs, making both societies unequal in terms of gender. It is remarkable that many women in both of the societies find the path to liberation and an existence free of subjugation in Buddhism taught and practiced at Larung Gar. The founder, Khenpo Jigphun, in fact rarely preached gender equality but created institutions in which women had the same opportunities as men, according to Liang and Taylor. The Khenpo believed in gender equality through the success of female practitioners rather than sloganeering for equality.[7]

Sinologist Ester Bianchi of the University of Perugia concluded that the Larung Gar Academy flourished and became a spiritual magnet for Han Chinese practitioners as the Tibetan Buddhist teachers catered to the spiritual needs of the disenchanted Han Chinese middle class submerged in the materialistic trend of contemporary Chinese society and a lack of spirituality. Secondly, the Tibetan teachers did not promote Tibetan Buddhism at the expense of Chinese culture but countered the ills of modernized Chinese society. Thirdly, the teachers propagated Buddhism not as a seal of identity based on Tibetan exclusivity but as a mental technology tool for humanity. And most importantly, the teachers and teachings of Larung Gar were non-confrontational toward the Chinese state.[8]

Despite being apolitical, practicing self-distancing from exile Tibetan politics and being non-confrontational to the state, Larung Gar is nonetheless feared by the CCP for its power to bring social change and equality by liberating minds in both Tibetan and Chinese societies. Although the CCP knows full well that Larung Gar is purely an academy for transforming the inner lives of its practitioners, the party envies and perceives the popularity and following of Larung Gar as metastasizing society in challenging the party’s political security.

Tibetan Buddhism in China’s National Security era

The Communist Party’s uneasy tolerance of the influence of Tibetan Buddhism and the Tibetan teachers in mainland China thus far has undergone significant changes, especially as current Chinese President Xi Jinping’s China shows many reversions to the early years of revolutionary China to coax but control Chinese nationalism. The Communist Party has resorted to classical Maoist tactics of a “friends and enemies” strategy to project Tibetan Buddhism and the tradition’s teachers as incompatible with modern socialist Chinese society and thus an enemy.

This is evident in the Communist Party of China’s orders to its apparatchiks down to the village level in China. A notice on “Niangziguan Town Program for Resolutely Waging the Tough Battle to Prevent and Defuse Major Risks” issued in May 2019 and obtained by the US—based Centre for Strategic and International Studies, carried an order in a long document to:

Prevent and crack down on infiltration by Tibetan independence separatist forces into this region. Go further in doing proper rectification work at key temples in accordance with the law and raise the level of management based on rule of law. Prevent and crack down on Tibetan separatist forces and contain the “eastward movement of Tibetan mysticism” [藏密东移]. Continuously manage Buddhist and Taoist commercialization, oppose using religious venues to conduct feudal and superstitious activities, and prohibit the illegal construction of large, open-air religious statues.[9]

Similarly, the government-approved Buddhist Association of Weibin District, Baoji City, Shanxi Province, order in May 2019 carried a prohibition on the spread of Tibetan Buddhism into the district. Document no. 2 (appended at the end of this report) obtained by the International Campaign for Tibet strictly prohibited Chinese Buddhist temples in Weibin district from inviting religious figures of Tibetan Buddhism or displaying physical attributes of Tibetan Buddhism in Chinese Buddhist temples.

Bouncing back?

Larung Gar Academy has survived the party and government’s interference several times in the past. The academy survived the authorities’ demolition of sections of it in 2001 and 2016. The authorities’ ceiling on the number of practitioners placed in 2001 did not deter the practitioners from reentering the academy in pursuit of their spiritual life. But that was during the relatively liberal period between the Cultural Revolution and Xi Jinping’s New Era. This is perhaps the first time in the academy’s 40 years of existence that the Chinese Buddhist practitioners have been singularly targeted by the authorities in the name of containing the “eastward movement of Tibetan mysticism.”

Since Xi Jinping’s presiding of the National Religious Work Conference in April 2016, Beijing has focused significantly on religious regulations in its larger governance effort by enacting multiple pieces of legislation to manage the Buddhist community’s activities.

However, the party is also wary of the fact that overregulating religious practice grows public discontent toward the party. With an estimated 185 to 250 million Buddhist faithful in China, the vast majority of who are Han Chinese, the question of public discontent against the party is real and too significant for the party to ignore.

Appendix

Document no. 2, 2019 issued by the Buddhist Association of Weibin District, Baoji City, Shanxi Province

Title of document: Prohibiting the spread of Tibetan Buddhism into Mainland China

Per a circulation issued by the Weibin district office for religious affairs, without the prior approval of authorities from the provincial, autonomous region, and municipality divisions, Chinese temples in Weibin district are prohibited from inviting religious figures of Tibetan Buddhism to perform religious activities, and displaying the following physical attributes of Tibetan Buddhism in their temples:

- Figures/effigies/statues of wealth deities and Tara;

- Prayer wheels that depict Tibetan and tantric texts, or images/figures of Tibetan Buddhism;

- Thangkas and prayer flags with Tibetan script;

- Circular or hemispherical designs/constructions that depict a stupa;

- Constructions or designs that depict the sun god;

- Symbols/insignias and posters that display Tibetan and tantric texts;

- Mandala plates

- Vajras, bells, and other religious objects of Tibetan Buddhism that display the mandala symbol; and

- Performing fire and smoke offering ceremonies; changing the satin clothing on Buddhist statues; engaging in Tibetan Buddhist debates; and participating in Tibetan Buddhist empowerment rituals.

The Buddhist Association of Weibin District, Baoji City, Shanxi Province, issued on 23 May, 2019

Footnotes:

[1] English translation of the Measures on the Administration of Internet Religious Information Services is available at Jeremy Daum’s China Law Translate. https://www.chinalawtranslate.com/en/internet-religious-information/ Chinese text of the law is available at http://cppcc.china.com.cn/2021-12/21/content_77943323.htm

[2] “Overseas Organizations, Individuals Not Allowed to Operate Online Religious Info Services within the Chinese Territory: Regulations,” Global Times, December 21, 2021, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202112/1242971.shtml.

[3] David Germano, “Remembering the Disembered Body of Tibet,” in Buddhism in Contemporary Tibet: Religious Revival and Cultural Identity (University of California Press, 1998). 53-94.

[4] Germano estimated 30 to 40 Han Chinese practitioners at Larung Gar Academy in 1991. At the peak of the academy’s flourishing, an estimated 10,000 practitioners studied at the academy in 2014-2015. The government later imposed a ceiling of 5,000 practitioners citing public health and safety in 2016.

[5] Jue Liang and Andrew Taylor, “Tilling the Fields of Merit: The Institutionalization of Feminine Englightenment in Tibet’s First Khenmo Program,” Journal of Buddhist Ethics 27 (2020), https://blogs.dickinson.edu/buddhistethics/?s=tilling+the+fields+of+merit.

[6] Liang and Taylor. 244.

[7] Liang and Taylor. 241.

[8] Ester Bianchi, “Teaching Tibetan Buddhism in Chinese on Behalf of Mañjuśrī: ‘Great Perfection’ (Dzokchen / Dayuanman 大圓滿) and Related Tantric Practices among Han Chinese and Taiwanese Believers in Sertar and Beyond,” in The Hybridity of Buddhism: Contemporary Encounters between Tibetan and Chinese Traditions in Taiwan and the Mainland. Edited by Fabienne Jagou, Études Thématiques, vol. 29 (Paris: École française d’Extrême-Orient, 2018), 236.

[9] Jude Blanchette, “How the CCP Governs: The View from a Chinese Town,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, January 11, 2021, https://www.csis.org/analysis/how-ccp-governs-view-chinese-town.