In recent decades, the Chinese government’s policy of establishing large commercial slaughterhouses in Tibet has faced increasing resistance by Tibetan herders and Buddhist leaders. The anti-slaughter movement activists face repression, intimidation and imprisonment for their opposition to the growth of slaughterhouses in their home area.

The ever-increasing number of slaughterhouses, established under the Chinese government’s programs of “poverty alleviation” for the Tibetan people, has affected Tibetan society deeply and brought the Buddhist ethos and value system into direct conflict with the state’s philosophy of modernization.[1]

Driven by concern for extensive animal suffering caused by the meat industry, prominent Tibetan Buddhist teachers have appealed to Tibetan herders not to participate in such large, industrialized efforts, which has led to the birth of an anti-slaughter or slaughter renunciation movement in contemporary Tibet.[2]

A Tibetan herder looks at a stolen yak being transported for slaughter. Photo: RFA

Tibetans herders are not traditionally vegetarians, as for more than 8,000 years, they have relied on breeding yaks for sustenance–using the animals to get meat, milk, hair and leather–to survive on the harsh climate of the Tibetan Plateau.

However, since the early 1990s, following China’s policy of economic reform, the Chinese government has promoted the establishment in Tibet of slaughtering businesses owned mostly by Chinese or Hui Muslims in the name of “poverty alleviation.” Facing increasing pressure to supply their livestock to the slaughtering businesses, Tibetan herders have been selling hundreds of thousands of yaks to the Chinese and Hui middlemen, who transport the livestock to urban markets every year. In some areas, local authorities bully the herders to “donate” their livestock to the slaughterhouses on a per household basis.[3]

As a counter to the increasing number of commercial slaughterhouses in eastern Tibet, and to Tibetans becoming market subjects in China’s economic reform, Tibetan Buddhist teachers have led the revival of religious sentiments in recent times by launching social initiatives to resist the commodification of animals for meat production.[4] Ethnographer Gaerrang observed that the resurgence of religious sentiments in contemporary Tibet against slaughtering animals is stronger than in the years before 1958.[5] China began its occupation of Tibet in 1959 after it spent most of the previous decade slowly gaining control of the country and forcing the Dalai Lama and many Tibetans into exile.

Since the Chinese government views expressions of Tibetans’ cultural identity as resistance to state-mandated neoliberal economic policy, the anti-slaughter movement is seen as challenging state power. For years, state law enforcement and local government authorities have cracked down on Tibetan Buddhist teachers and anti-slaughter movement activists in Tibet.[6] The national action against “underworld forces” launched in 2018 sought to pin down the activists and curb the influence of the anti-slaughter movement.[7] The rationale of the campaign is simple: anyone obstructing state development projects is challenging state power and authority.

Yak beef for China proper’s diet

Increasing beef consumption in China has led authorities to integrate yak herding into the market economy. It has also led China to import beef from countries like Brazil, Uruguay, Australia, New Zealand, Argentina and others. China is a net importer of beef from other countries despite ranking third in the world for beef production.[8]

To increase domestic beef production, Chinese authorities have industrialized beef to transform traditional practices. Industrialization meant the presence of large-scale slaughtering enterprises in Tibet to tap into its livestock capital. Tibetan yaks have been seen as a supply solution to meet the growing demand for meat in compact Chinese heartland towns and cities. Provincial commerce departments facilitate large conferences for Chinese businesses to discuss and coordinate cold chain transportation of animal products from Tibetan areas to bridge the gap between supplies from their place of origin and demands from their place of consumption.[9] The enterprises also participate in large-scale shopping fairs to sell their meat products far and wide within China and globally.[10]

State-funded animal husbandry research centers were also tasked to produce new breeds of yak that are better suited for large-scale intensive breeding in the cold and arid alpine areas of the Tibetan Plateau. One such new breed is the Ashidan yak produced by the Lanzhou Institute of Husbandry and Pharmaceutical Sciences of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Chinese state media news outlet Xinhua was not shy in claiming that the yak “… is expected to help herdsmen on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, known as the ‘roof of the world,’ out of poverty.”[11]

Chinese enterprises make “poverty alleviation” yak meat products

Yaks, or simply “wealth on hooves,” as the nomads put it, are in abundance on the Tibetan Plateau. More than 14 million yaks, accounting for 94% of the world’s yak population, live on the plateau. More than one-third of the yak population, or 5 million yaks, live in the Tibetan region that is the source of three great rivers of Asia: the Machu (Yellow), the Drichu (Yangtze) and the Dzachu (Mekong). The Tibetan areas in Gansu province have the fifth largest pastoral areas, with 900,000 yaks in 1997.[12]

China Daily, another state media outlet, reported in October 2018 that Kanlho (Gannan) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Gansu province produced 79,000 tons of meat products in 2017.[13] The same report revealed that the added value of animal husbandry at 2.2 billion yuan in 2017 was a 20% increase over three years. In the neighboring Tibetan areas in Qinghai province, Qinghai Daily covered the scale of the yak meat industry. According to a report from Qinghai Daily, Qinghai province accounts for about one quarter of total beef and mutton production in China.[14] About 100,000 tons of yak meat and mutton are sold outside the province annually. With more than 500 processing enterprises and 11 national-level leading enterprises engaged in yak meat, milk and wool production, more than 200 types of products are made.

SF Cold Chain signed a Memorandum Of Understanding with Qinghai 5369 Ecological Animal Husbandry Technology Co., Ltd. during the Gansu and Qinghai Beef and Mutton Production and Marketing Internet Conference in November 2016.

Yak slaughter plants have also been constructed in the Tibet Autonomous Region. Tibet Satellite TV News Network reported that a “modern and most advanced” Lhasa Damshung Slaughter plant financed by Tibet Financial Leasing Co. started trial operation in Damshung (Dangxiong) County in October 2019.[15] Another slaughterhouse owned by Tibet Shengjia Food Development Co. in Chushul (Qushui) County was reported to specialize in integrating food processing technology research and development, cattle and sheep slaughter, cold storage, division and sales, livestock byproduct sales and logistics distribution, according to a Tibet Business Daily report.[16] Quoting the Tibet Autonomous Region Animal Health and Plant Quarantine Supervision Institute, the report states that 36,150 livestock and poultry were slaughtered in the first quarter of 2019. In 2017, China Daily reported that the TAR produced 190,400 tons of yak meat; an increase of 10,400 tons compared to 2016.[17] In other words, 583,800 yaks were slaughtered in the TAR alone in 2017.[18]

Chinese enterprises and their “poverty alleviation” products

Qinghai Kekexili Industrial Development Group Co., Qinghai Northwest Jiao Group and Qinghai 5369 Ecological Animal Husbandry Technology Co. are some of the leading enterprises producing yak meat products in Qinghai province. Some of these businesses’ yak meat products are reproduced below for illustration.

Northwest Jiao brand of Qinghai Beijiao Group boasts of a 140 yak-beef products portfolio. The group trades 300,000 yaks and 200,000 Tibetan sheep annually and slaughters and processes 150,000 yaks and 100,000 Tibetan sheep.

A yak meat package sold under the brand of “Kekexili” of state enterprise Qinghai Kekexili Industrial Development Group Co. covers more than 80 large cities and supermarket chains in 23 provinces and cities in China.

Qinghai 5369 Ecological Animal Husbandry Technology Co. boasts that its high-end yak meat products, which it pitches as a nutritional supplement for athletes in sports training bases, have a higher nutritional value than ordinary yak meat. Processing 60,000 yaks in a year, 5369 group is located in Chigdril (Chinese: Jiuzhi) county in Golog (Guoluo) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. Besides the Chinese market, the group also sells in Middle Eastern countries.

Tibetan Buddhist teachers challenge the meat industry

Tibetan Buddhist teachers counter the increasing commodification of animals for meat production. This trend has concerned the Tibetan Buddhist teachers for a long time.

Scholar Geoffrey Barstow argues that the earliest interventions of religious teachers against eating meat in Tibet date back to the 11th and 12th centuries and to the Indian Buddhist scholar Atiśa; his Tibetan disciple Dromtön Gyelwé Jungné; the Tibetan Bön master Metön Sherab Özer; and the Tibetan Buddhist monk Pakmodrupa and his two primary disciples, Jigten Sumgön and Taklung Tangpa.[19] Metön Sherab Özer, in critiquing meat consumption in his “Vinaya Compendium,” taught:

By definition, this thing called “meat” comes from the killing of animals. Being without mercy sends one to hell. With great regret, abandon eating it. This thing called “meat” comes from a father and a mother. These are its causes and conditions. If you saw this with your eyes, you would tremble with fear. How pitiful it would be to take it in your hands! Just smelling it brings on nausea. Once it is tasted by the tongue, how can it be kept down? For these reasons, it should be abandoned.[20]

In recent times, Tibetan Buddhist leaders have used their moral authority to initiate a slaughter renunciation movement to encourage Tibetan nomads to stop selling their livestock to the commercial slaughterhouses.

Most notable among the teachers in the movement was the late Khenpo Jigme Phuntsok (1993-2004) of the Larung Gar Buddhist Institute, who first initiated it in 2000.[21] Tibetan herders are predominantly Buddhist by religion, and Khenpo’s tremendous influence on them made a profound impact on the meat industry.

Ethnographer Gaerrang Kabzung noted that during a teaching in 2000, Khenpo described the horrific conditions inside the slaughterhouses:

Inside of some local slaughter buildings the scene is similar to what we imagine as the town of death, full of terrifying noises including the sound of machines used to process meat, the sound from sliced throats, the sound of running blood, and moos of livestock in a deadly panic. Some yaks were too frightened to go inside the building, so butchers have to pull their eyes out so that they would become easier to move into the building…once they are in the building, a machine with lifting hook would bring a hind leg of the yaks into the air; when a butcher slices the throat of yaks, hot blood and cud eject out of the throat while the yaks are struggling with no hope of survival, but before they are totally dead, their skins are striped off and the innards removed.

Eleven years later, the Tibetan writer and activist Tsering Woeser described similar terrors in a blog post:

My friend said that he had once witnessed the modern industrialised slaughtering methods. The workers simply use their fingers to push some central button and two metal racks which had been open suddenly close in, hereby clutching a yak of an enormous size so that it cannot move anymore; once more, the workers use their fingers to press some button and the wedged yak is suddenly being lifted into mid-air and its body is turned around. What follows is a machine initiating the slaughtering process, which happens in an instant, an entire living yak is being dismembered, flesh with flesh and bones with bones. My friend said that when the yak was being turned around he saw big teardrops coming from the animal’s eyes. Tibetans are of course also killing yaks, but only in limited numbers, and never like those processing plants engaging in continuous killings on a daily basis. Seeing the blood that flows out of the factory colouring the grasslands red, smelling the blood coming out of the factory saturating the air, of course the Tibetans in Mani Gego cannot keep quiet.

Lack of economic benefit for Tibetans

Khenpo Jigme Phuntsok.

Photo credit: Terton Sogyal Trust

Besides using the Buddhist philosophy of accumulating negative karma to persuade the herders not to sell their livestock to slaughterhouses—and through the notion, linked to Buddhist ideas of reincarnation, that an animal could be your mother in a previous life—Khenpo Jigme Phuntsok also showed the herders that sinful business activity has never brought economic prosperity in Tibet. He taught,

from a this-worldly perspective, the business involved with killing will never bring economic improvement. I personally have never seen any middlemen, who do the livestock trading business between Tibetan pastoral areas and nearby Chinese cities, make money from their sinful business. I saw many slaughterhouses in Tibet that have slaughtered millions of livestock for many years go bankrupt one after another.[22]

After Khenpo passed away, his students, primarily Khenpo Tsultrim Lodoe, continued the initiative. Initially launched in Serthar (Seda) county in eastern Tibet, the slaughter renunciation movement resonated with herders and quickly gained momentum all across the Tibetan Plateau. In studying “The case of the disappearance of Tibetan sheep from the village of Charo in the eastern Tibetan plateau,” ethnographer Ga Errang notes that:

Though the Tibetan herders in this village (Charo village in Dawa County in Sichuan province) did not participate in the movement (anti-slaughter movement) directly, nor did the lamas in the village teach them to do so, their exposure to the general atmosphere of religious revival in some areas has nevertheless led them to become more aware of Buddhist norms, such as sin, karma and compassion, in their everyday life.[23]

Outlawing the anti-slaughter movement

Unlike the traditional Buddhist ritual of “tsethar” (life liberation) involving freeing a small number of animals from the brink of death, the slaughter renunciation movement required herders to refrain from selling off their livestock to the slaughterhouses for at least a fixed number of years or for one’s entire life. Herders heeding the words of the Buddhist teachers brought about a dramatic decrease in the number of livestock available to the slaughtering enterprises.

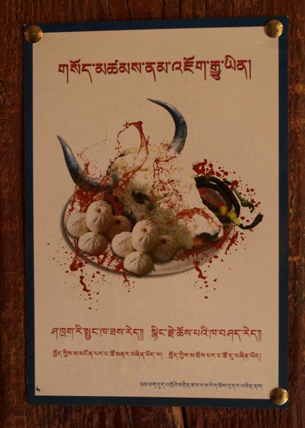

Vegetarianism promotional flyer photographed near Samye, Tibet, in 2011 via Radio Free Asia.

Multiple incidents involving the slaughterhouses or related to them became prominent. By and large, the incidents were peaceful, but a few turned violent as either Tibetan herders burned down slaughterhouses or the police fired live ammunition on Tibetan herders who clashed with slaughterhouse owners.[24] Chinese authorities also began targeting any Tibetans involved in liberating animals from imminent slaughter. An incident widely reported was the authorities’ arrest of three monks from Golok in eastern Tibet in mid-2013 after they saved 300 yaks from slaughter.[25]

Authorities have issued legal measures penalizing Tibetans active in the anti-slaughter and tsethar movement. For example, Malho Prefecture’s “Twenty Illegal Activities Related to Tibet Independence,” issued on Feb. 12, 2015, conflated anti-slaughter or life liberation movements with separatism. Article 20 in the illegal activities stipulated that Tibetans “obstructing the ‘killing or selling of livestock’ [policy], forcibly “liberating [the animal’s] life,” would be deemed as “separatist” and dealt with as such under the law.[26] Similarly, the Chamdo Prefecture “Notification on Striking Hard and Eliminating Illegal Organizations and Illegal Activity by Social Organizations According to Law,” issued on March 20, 2014, outlawed the anti-slaughter movement. Article 10 in the law stipulated that the anti-slaughter activists advocating “stop animal slaughter” and “stop eating meat” will be punished under article 276 of the criminal code, which could be imprisonment for three years or more.[27]

The launch of the broad, three-year national action against “underworld forces” in 2018 also targeted Tibetans expressing their opinion on eating meat or participating in the anti-slaughter movement. While this campaign focuses on mafia activities in mainland Chinese provinces, it is also used to suppress social initiatives like slaughter renunciation in Tibet. The campaign against “underworld forces” targets anyone perceived by the government as disrupting economic order and endangering government authority.[28] In a widely publicized trial of 10 Tibetans in Sangchu (Xiahe) County in Gansu province, the county court, after two days of trial on June 28-29 of this year, sentenced the 10 Tibetans to lengthy prison terms (eight to 13 years) for their objection to a slaughterhouse in their home area.[29]

Slaughter renunciation movement goes on

The proliferation of commercial slaughterhouses in Tibet has a negative impact on Tibetan culture and ethos. The rigorous promotion of slaughter enterprises goes against the herders’ traditional practice of sustainable, needs-based animal slaughter that evolved on the Tibetan Plateau over thousands of years. Although the anti-slaughter movement is an expression of Tibetan ethos, it is viewed by the Chinese government as obstructing development projects and challenging the state’s power and authority to “modernize” Tibetan society. Despite political and legal measures adopted by the state, the slaughter renunciation movement has resonated with Tibetan herders all across the Tibetan plateau. The movement goes on.

Footnotes:

[1] Gaerrang (Kabzung), “Contested Understandings of Yaks on the Eastern Tibetan Plateau: Market Logic, Tibetan Buddhism and Indigenous Knowledge,” Area 49, no. 4 (December 1, 2017): 526–32.

[2] Geoffrey Barstow, “Epilogue: Contemporary Tibet,” in Food of Sinful Demons: Meat, Vegetarianism, and the Limits of Buddhism in Tibet (Columbia University Press, 2017), 312 Pages.: 193-194.

[3] “‘No One Has the Liberty to Refuse’: Tibetan Herders Forcibly Relocated in Gansu, Qinghai, Sichuan, and the Tibet Autonomous Region,” accessed August 24, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/reports/2007/tibet0607/ : 68.

[4] Gaerrang Kabzung, “ALTERNATIVE DEVELOPMENT ON THE TIBETAN PLATEAU: THE CASE OF THE SLAUGHTER RENUNCIATION MOVEMENT” (PhD thesis, University of Colorado, 2012), https://scholar.colorado.edu/downloads/vm40xr68c.

[5] Gaerrang, “The Case of the Disappearance of Tibetan Sheep from the Village of Charo in the Eastern Tibetan Plateau. Tibetan Pastoralists’ Decisions, Economic Calculations, and Religious Beliefs,” Études Mongoles et Sibériennes, Centrasiatiques et Tibétaines, no. 50 (March 4, 2019), http://journals.openedition.org/emscat/3881 : 13.

[6] “Three Tibetan Monks Detained for Freeing Yaks Headed to Slaughter,” Radio Free Asia, accessed August 25, 2020, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/tibet/yaks-02192014162424.html. “China: Fears for Tibetan Slaughterhouse Detainees,” Human Rights Watch, March 30, 2006, https://www.hrw.org/news/2006/03/30/china-fears-tibetan-slaughterhouse-detainees.

[7] “Tibetan Land Protesters Get Lengthy Jail Terms in Action Against Gansu Slaughterhouse,” Radio Free Asia, accessed August 25, 2020, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/tibet/lengthy-07152020182018.html.

[8] Xiang Zi Li, Chang Guo Yan, and Lin Sen Zan, “Current Situation and Future Prospects for Beef Production in China — A Review,” Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences 31, no. 7 (July 2018): 984–91.

[9] “Qinghai Beef & Mutton Production-Marketing Internet Conference Ended Successfully,” accessed August 15, 2020, https://www.sf-express.com/cn/en/news/detail/Qinghai-Beef-Mutton-Production-Marketing-Internet-Conference-ended-successfully/.

[10] “Shopping Fair in Sichuan Gathers Global Goods – Headlines, Features, Photo and Videos from Ecns.Cn|china|news|chinanews|ecns|cns,” accessed August 16, 2020, http://www.ecns.cn/2014/01-16/97321.shtml.

[11] “Newly-Bred Yaks Help Herders on ‘Roof of World’ out of Poverty – Xinhua | English.News.Cn,” accessed August 19, 2020, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-07/01/c_138189324.htm.

[12] “Part 1 Yak Production in Six Provinces (Regions) in China by Han Jianlin,” accessed August 19, 2020, http://www.fao.org/3/ad347e/ad347e0n.htm.

[13] 宋薇, “Gansu’s Gannan: Harmony in Paradise – Chinadaily.Com.Cn,” accessed August 3, 2020, //global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201810/16/WS5bc53212a310eff303282861.html.

[14] Tan Mei, “头牦牛的自述 (The Narrative of a Yak),” Qinghai Daily, April 22, 2020, https://www.qhlingwang.com/xinwen/qinghai/2020-04-22/338260.html.

[15] “【公司要闻】西藏卫视新闻联播:西藏自治区首个现代工艺牦牛屠宰厂在当雄投入试运行-西藏金融租赁有限公司官方网站 ‘[Company News] Tibet Satellite TV News Network: The First Modern Craft Yak Slaughter Plant in Tibet Autonomous Region Puts into Trial Operation in Dangxiong,’” accessed August 19, 2020, http://www.tibetfl.com/newsitem/278430560.

[16] “Tibetan Yak Meat Must Go through at Least Seven Quarantine Inspections to Control Quality_Tibet_Tibet Window of China,” accessed August 19, 2020, https://www.chinatibet.net/news/tibet/202004/t20200422_21443.shtml.

[17] 刘小卓, “Winter in Tibet Is the Time for Making Meat Jerky – Chinadaily.Com.Cn,” accessed August 20, 2020, //global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201801/05/WS5a4f54d9a31008cf16da55cc.html.

[18] The figure for 583,800 yaks slaughtered in 2017 was calculated on the basis of a yak carcass in Tibet weighing 170 kg as per the data provided in Gerald Wiener, Han Jianlin, and Long Ruijun, “Meat Production,” in THE YAK, Second Edition (Bangkok, Thailand: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific, 2003), http://www.fao.org/3/ad347e/ad347e00.htm#Contents.

[19] Geoffrey Barstow, “A Brief History of Vegetarianism in Tibet,” in Food of Sinful Demons: Meat, Vegetarianism, and the Limits of Buddhism in Tibet: 31.

[20] This excerpt is quoted from Barstow, “Epilogue: Contemporary Tibet.” on page 32.

[21] For a brief biography of Khenpo Jigme Phuntsok, see “Khenpo Jigme Puntsok – The Treasury of Lives: Biographies of Himalayan Religious Masters,” April 29, 2015, https://web.archive.org/web/20150429121653/http://www.treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Khenpo-Jigme-Puntsok/10457.

[22] This excerpt is quoted from Gaerrang Kabzung, “ALTERNATIVE DEVELOPMENT ON THE TIBETAN PLATEAU: THE CASE OF THE SLAUGHTER RENUNCIATION MOVEMENT.” : 122.

[23] Ga Errang, “The Case of the Disappearance of Tibetan Sheep from the Village of Charo in the Eastern Tibetan Plateau. Tibetan Pastoralists’ Decisions, Economic Calculations, and Religious Beliefs,” Études Mongoles et Sibériennes, Centrasiatiques et Tibétaines, no. 50 (March 4, 2019): 12.

[24] “Tibetans Attack Slaughterhouse,” Radio Free Asia, accessed August 18, 2020, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/tibet/attack-12012011141021.html. Police Fire on Tibetan Villagers to Help Chinese Cattle Thieves, Two Are Serious,” Tibetan Review (blog), April 3, 2016, https://www.tibetanreview.net/police-fire-on-tibetan-villagers-to-help-chinese-cattle-thieves-two-are-serious/.

[25] “Saving Yaks from Slaughter Criminalised by China | Free Tibet,” accessed August 18, 2020, https://www.freetibet.org/news-media/na/saving-yaks-slaughter-criminalised-china.

[26] “Praying and Lighting Butter-Lamps for Dalai Lama ‘Illegal’: New Regulations in Rebkong,” April 14, 2015, https://savetibet.org/praying-and-lighting-butter-lamps-for-dalai-lama-illegal-new-regulations-in-rebkong/.

[27] Human Rights Watch (Organization), ed., “Illegal Organizations”: China’s Crackdown on Tibetan Social Groups (New York, New York: Human Rights Watch, 2018): 64.

[28] “Crackdown on Underworld Forces,” China Law Translate (China Law Translate, March 23, 2018), https://www.chinalawtranslate.com/criminal-procedure-2/扫黑除恶专项斗争/.

[29] “Tibetan Land Protesters Get Lengthy Jail Terms in Action Against Gansu Slaughterhouse,” Radio Free Asia, accessed August 25, 2020, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/tibet/lengthy-07152020182018.html.