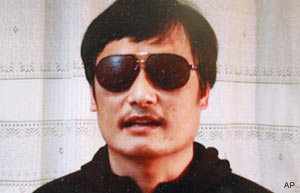

Blind legal activist Chen Guangcheng as seen in a video posted to YouTube on April 27, 2012.

Chen’s escape to the American Embassy in Beijing, on the eve of the Strategic and Economic Dialogue, upended its planned agenda. In addition to preparing for their bilateral engagement with the Chinese, U.S. diplomats found themselves negotiating over the fate of Chen and his family in, according to Secretary Clinton, “a way that reflected his choices and our values.”

We don’t know whether the diplomats saw this as a distraction, as some commentators speculate. But it is fair to say that they have devoted more energy to human rights this week in Beijing than they had planned, given that the human rights are generally compartmentalized into the ‘difficult issues” section of the Dialogue. This is both useful and significant, as it exposes the fundamental fault in the way that the U.S. government (across Administrations) have approached the Chinese.

While the situation is still fluid, it appears that the Chinese from the outset were not willing to live up to the assurances that the U.S. said it had negotiated. This raises a fundamental question: if the Chinese cannot be trusted a deal on the fate of one individual, how trustworthy can they be on the agreements sought by the U.S. government within the Strategic and Economic Dialogue?

Chen’s case (not to mention the daily experiences of millions of repressed Tibetans) exposes the fact that there is no legitimate rule of law in the People’s Republic of China. “Rule of law” is merely a euphemism for the exercise of political power by the Communist Party, adjudicated per the whims and the interests of the Party and its leaders.

Rather than being in a side session of the major Dialogue, human rights and accountable rule of law must be essential and integrated components of all aspects of the bilateral relationship. Until this fundamental flaw is corrected, the U.S. will continue to struggle to reach, much less enforce, mutually respected deals with the Chinese on economic or security matters, much less the living conditions of human rights defenders.

The Obama Administration has cited the Chen case as a model for its vision 21st Century Statecraft, where traditional government-wielded foreign policy tools are complemented by the actions of civil society, non-governmental organizations, the media and global netizens. In this, the Administration is both relying on and empowering these groups to aid in the cause of protecting Chen through vigilance and advocacy. But at the same time, the Chen case demonstrates the primacy of the government role. It was the U.S. Embassy government in which Chen sought refuge, and the U.S. government to which Chen is appealing to protect his family. It was the U.S. government who negotiated the Chen’s “deal” with the Chinese, and it is the U.S. who now bears the burden for the protection of Chen and his family.

It is not accidental that Chen Guangcheng and Wang Lijun (the former Chongqing security chief Wang Lijun, although under far different circumstances) fled to American diplomatic posts. This demonstrates that the United States remains not only the beacon of freedom for the people of China and Tibet, but also serves as their international lawyer. Absent the ability to seek fair redress in the party-controlled Chinese legal system, these individuals (and going back a generation, Fang Lizhi, who recently passed away), are forced to turn to the U.S. for legal representation, based on its values and legal principles, for refuge and recourse.