Harsh security measures have been imposed in a Tibetan township in Kardze (Chinese: Ganzi), the Tibetan region of Kham, after two rare protests in November calling for Tibetan independence and the return of the Dalai Lama.

The protests, involving four monks and two young laymen who are now in detention, were sparked by distressing political campaigns imposed on local nomads whom the Chinese government had forced to give up their land and livelihoods. Many were also compelled to remove images of the Dalai Lama, replace them with pictures of Chinese leaders and praise the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Armed police arrived in a large convoy in Wonpo township (Chinese: Wenbo) after two separate protests in November. Wonpo township is located in the lower Dzachukha region of Sershul (Chinese: Shiqu) county in Kardze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in the Chinese province of Sichuan. Tibet, a historically independent country, was annexed by China 60 years ago and has been brutally occupied ever since.

The main street of Wonpo in Sershul in late November following the protests and crackdown.

Monks protest

One protest involved four monks from the local Dza Wonpo Ganden Shedrub monastery who were detained after scattering leaflets. The second protest involved two young men who held a protest in solidarity with the monks, both calling for Tibetan independence and expressing loyalty to the Dalai Lama. Given the already intense security restrictions in the area, such protests have been increasingly rare since 2008, when a wave of mostly peaceful protests spread across Tibet.

The monks, identified by Tibetan exile sources as Kunsal (20 years old), Tsultrim (18), Tamey (18), and Soeta (18), were seized by police in their rooms at Dza Wonpo monastery after they scattered leaflets in the courtyard of the Chinese administrative office located across the road from the monastery on Nov. 7. Police later detained the monks’ religious instructor, Shergyam Yang, a teacher at the monastery, but released him after 11 days, according to Jampa Yonten, a former monk from Dza Wonpo monastery who is now a monk in South India.

According to Jampa Yonten, the leaflets called for independence for Tibet and for human rights and for rights of local people to be respected. The protest appeared to be a response to Chinese government efforts to coerce local nomadic people—who were forced to vacate their land—to display images of China’s leaders, including Chairman Xi Jinping, and to praise the CCP in videos that state media could circulate. Those measures reflect a deepening anti-Dalai Lama campaign in the area, which has included raids on people’s houses to check that they are not keeping any images of the Tibetan religious leader.

Second protest

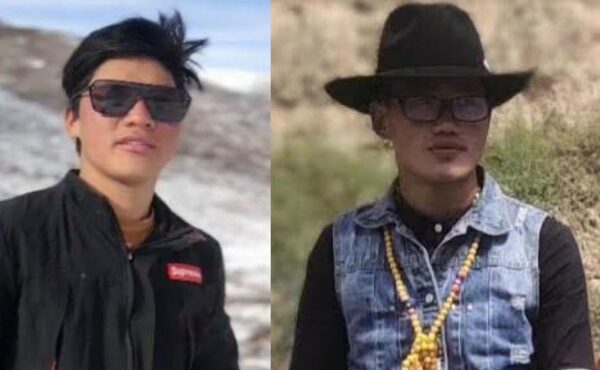

Two weeks later on Nov. 21, two young Tibetan laymen named Choegyal and Yonten were arrested after they distributed leaflets in front of a police station in Dza Wonpo village and expressed their solidarity with the arrested monks in posts on the social media platform WeChat. The two young men recorded a video clip prior to the protest showing the Dalai Lama and leaflets with “Bod Rangzen” (“Independence for Tibet” in Tibetan) written repeatedly in red and black ink. The video was shared online by Tibetan exile media.

Detained Tibetan protester Yonten is shown in an undated photo obtained by the Tibetan service of Radio Free Asia

According to the same source, another monk named Nyimey, identified as the brother of Choegyal, was taken into custody on Nov. 18 after posting online expressions of support for the actions of those in prison. He was later released.

Resistance and resilience in Sershul

Chinese policies have caused deep suffering in Sershul, and from the resistance of the 1950s and ’60s to the protests today, Tibetans in Kham are known for fiercely protecting their Tibetan identity.

In the Sershul area, Tibetan nomads have been forced to settle and to reduce their livestock, which has increased poverty as families are left without a livelihood. Government subsidies are insufficient for living costs. Compounding their distress, the local people have been pressured by the Chinese government to demonstrate their loyalty to the CCP. They have been required to receive official delegations and make statements to cameras for dissemination by official media.

Jampa Yonten said: “The pressure has been particularly intense since the 70th anniversary of the [founding of the People’s Republic of China on Oct. 1, 2019], and settled nomads have also been required to display images of party leaders in their homes, just as they have across other areas of Kham and also in Amdo and the Tibet Autonomous Region. Every benefit they receive from the government is dependent upon this fake display, from raising Chinese flags to displaying images of Xi Jinping.”

According to local sources, some nomads have refused to participate in these government propaganda exercises, creating divisions in the community and endangering individuals.

Expressions of solidarity by two protesters

Choegyal and Yonten, the two young laymen who protested with leaflets, also published online, under pen names, short verses expressing their pride in their Tibetan identity and solidarity with others who have made sacrifices for Tibet.

Images of the two lay protesters Choegyal, known by the pen name “Drongdzi,” and Yonten, known by the pen name “Yangchenpa,” published by The Tibet Post International and other exile media.

According to a translation by Tibetan exile news outlet The Tibet Post, Yonten, known by his pen name Yangchenpa, wrote: “Heroes who [have] sacrificed their lives for the welfare of our nationals/And the fighters who continue their struggle for independence of Tibet/I have had heard you were gone through the genocide, torture, and tyranny [sic] /Because our compatriots from Wongpo village are now fighting for freedom/They were forcefully brought into the dark prison, I felt deeply saddened/I will also come up [arise] later, my compatriots!”

Choegyal, known by his pen name Drongdzi, wrote a verse entitled “Discourse”: “I have no knowledge of magnificent prosody/I have no exquisite writing skills/I also have no education of high-ability and knowledge/But our national great pride lies on our shoulders/Never give up!”

Town under lockdown since protests

Since the protests in November, Dza Wonpo has been under lockdown, with an increased number of troops deployed and a large number of plainclothes police operating in the town, intensifying their surveillance of people’s everyday lives. This has led to distrust and fear, with many people staying in their homes. Images of the main street taken soon after the protest by Choegyal and Yonten show nearly deserted streets in contrast to the usually busy roads.

According to the same sources, more aggressive sessions of “political education” are underway at Dza Wonpo monastery, with certain monks forced to attend. As is common across monasteries in Tibet, a police station is located inside the monastic complex, with additional surveillance administered by the nearby local government headquarters.

Since 2014, the International Campaign for Tibet has monitored a trend of peaceful solo protests in areas of eastern Tibet. This is particularly evident in Kardze, where the November protests occurred, and in Ngaba (Chinese: Aba), also in Sichuan. These areas have also been the site of numerous self-immolations. As a result, there appears to be a correlation between the occurrence of both peaceful protests and self-immolations in these two areas and high levels of securitization. In 2016, per capita domestic security expenses in Tibetan areas of Sichuan were nearly three times higher than for Sichuan province as a whole. Domestic security spending in Ngaba and Kardze grew by 295 percent between 2007 and 2016.

The peaceful November protests seem to reflect a wish by protestors to make a strong statement about freedom and loyalty to the Dalai Lama without undertaking the more extreme act of self-immolation, which Tibetans now know can lead to untold suffering for families and friends. The Chinese authorities have responded to the more than 150 self-immolations in Tibet with an intensified wave of repression and by punishing those allegedly ‘associated’ with those who set themselves on fire, including friends, families and entire communities.

Crackdowns at Dza Wonpo monastery

Dza Wonpo is an important monastery in the area that has a history of protest, resistance and crackdown, from the 1950s onwards. Jampa Yonten explains that it was taken over as a Communist Party headquarters in the early years of China’s occupation and was not returned to the monastic community until the 1980s, following interventions on its behalf by the 10th Panchen Lama, a major Tibetan Buddhist leader. The monastery was rebuilt by local people during the period of relative liberalization that followed Chairman Mao’s Cultural Revolution.

Dza Wonpo was subject to a tight crackdown after the protests of March 2008. Eight monks from the monastery who were studying in Lhasa were imprisoned, with one, Lodroe, finally released in 2018 after serving a 10-year sentence for participating in a protest. A Tibetan source told Radio Free Asia: “He had taken part in the March 2008 uprising in [Tibet’s capital] Lhasa, and was carrying the Tibetan national flag and calling out for freedom for Tibet when he was arrested.”

The crackdown in the area intensified further in 2012 when monks at the monastery refused to hoist Chinese national flags, leading to scores of arrests and raids on people’s homes.

In 2015, when Chinese authorities announced that they would award large sums of money to Tibetan monasteries in the area that had steered clear of protests, Dza Wonpo monastery was not a recipient. Instead, there was a tightening of “patriotic education” at Dza Wonpo, according to local sources.

In 2013, the Chinese authorities prevented the body of a Tibetan nomad who self-immolated from being taken to Dza Wonpo monastery for funeral rites. According to Jampa Yonten, Tenzin Sherab, who was in his early 30s, set fire to himself and died on May 27, 2013, in the Gyaring area of Yushu in Qinghai province. His nomad family had been resettled to Chumarleb under Chinese authorities’ policies of settlement, land confiscation and fencing of pastoral areas inhabited by Tibetans.

A few days before his self-immolation, Tenzin Sherab talked to friends about the difficulties of life due to Chinese policies, and his fears for the survival of Tibetan culture and religion, saying that he could no longer tolerate the “repressive measures in Tibet.”