China’s Tibet policy has been a subject of international scrutiny ever since its invasion and subsequent occupation of Tibet in 1959. The Chinese government knows that there is a political problem in Tibet. But rather than resolve it, one of its approaches is to falsify the situation and employ various methods to control the narrative around Tibet, aiming to reshape its portrayal in global discourse. This report examines China’s recent external propaganda efforts concerning Tibet, highlighting the objectives and the tactics.

China’s external propaganda efforts regarding Tibet have been a complex and multifaceted undertaking, spanning decades and utilizing diverse channels and strategies. In the first four decades following the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, China suffered significant damage to its international image. Mao Zedong’s invasion of Tibet, China’s conflicts with neighboring nations, the calamitous Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution all inflicted immense harm on China’s reputation in the global community.

Deng Xiaoping, who succeeded Mao, introduced market reforms aimed at altering China’s trajectory, but the Tiananmen Square Massacre in 1989, occurring under his rule, further tarnished China’s image, the repercussions of which persist to this day.

Subsequent leaders, including Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, intensified China’s external propaganda activities to rehabilitate and enhance the country’s international standing, portraying China as a peaceful and developing nation.

Accordingly, Beijing took specific steps to impact the international perception of its conduct in Tibet. In 1993 a secret two-day “Conference on the Work of the External Propaganda on the Question of Tibet” was held in Beijing by the Chinese government to review its strategy. From leaked documents of the meeting, which the International Campaign for Tibet had obtained and subsequently published,[1] it was clear that the foremost concern of the Chinese government was how to address the challenge of the loss of the propaganda war internationally over Tibet. One document of the meeting talked of how “the distorted propaganda and attacks of the Dalai Cliques and international enemy forces still enjoy a large market in the world”.[2] The meeting recommended that among other things, “Multi-level and different forms of vivid and lively propaganda should be carried out regarding sovereignty and human rights record. Its aim is to promote the further understanding on the part of the overseas people of the question of Tibet so as to eliminate the impact created by the Dalai Clique and the international enemy forces through their distortions and attacks against us … and to win the support and sympathy of the overseas people for us”.[3]

Many recommendations made at the Beijing meeting were incorporated into decisions of the 1994 Third Forum on Work in Tibet. The Third Tibet Work Forum marked an official end to moderate policies and a dramatic increase in political repression. The situation in Tibet following this meeting saw tighter internal security, longer prison sentences for political activism, increased control over monasteries and nunneries, intensified political education in schools and more detentions. The forum identified the influence of the Dalai Lama and the “Dalai clique” as the root of Tibet’s instability. Officials at the third work forum described the Tibetan independence movement as a snake, and their attempts to “cut off the serpent’s head” led to restrictions of the spread of Buddhism and a political campaign to destroy the religious as well as the political standing of the Dalai Lama.[4]

Comprehending the international community’s sympathy for the Tibetan cause, during Jiang Zemin’s term, dialogue was restarted in 2002 between his officials and the Dalai Lama’s envoys. This was continued under Hu Jintao and extended into the years leading up to the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics, finally ending in 2010. Some China watchers are of the view that the talks with the Dalai Lama’s envoys were merely a pretense, aimed at temporarily alleviating international criticism of China’s actions in Tibet until the conclusion of the Olympics.

Since 2008, human rights in Tibet have deteriorated greatly. Tibetans’ ability to engage in religious activities, move and associate freely, express concerns, access information and enjoy due process is severely curtailed. Their right to enjoy a healthy environment, access resources to achieve an adequate livelihood and access Tibetan-medium language education is also restricted.

The pivotal year of 2008 marked Beijing’s decisive move to accelerate its efforts to control the narrative surrounding Tibet. This strategy included a dual approach, to curtail the outflow of stories depicting its atrocities and to propagate its own narrative on Tibet. There was thus a policy aimed at halting the exodus of Tibetan refugees from Tibet, partly to halt the dissemination of their accounts of Chinese atrocities.

In 2009 there were strategic substantial investments (approximately US $7.25 billion, according to Professor Anne-Marie Brady of the University of Canterbury) for “big propaganda” (Chinese: da waixuan) to bolster international news coverage on China and enhance its global presence.[5] This dual strategy, aimed at curbing the dissemination of Tibetan accounts while actively promoting China’s perspective, has remained in effect for the past 15 years, showcasing Beijing’s persistent efforts to control the discourse on Tibet.

External propaganda in Xi Jinping era

Xi Jinping emphasized early in his tenure the importance of external propaganda in shaping China’s global image and narrative. On Aug. 19, 2013, during his address to the National Propaganda and Ideology Work Conference, Xi advocated for “innovation” in China’s external propaganda efforts, promoting the idea of effectively “telling China’s story.”[6]

Xi highlighted the necessity for meticulous and adept external propaganda, urging innovative methods that blended Chinese and external elements to effectively communicate China’s narrative. He emphasized the importance of creating new concepts, categories and expressions to articulate China’s perspective and voice on the global stage.

Taking advantage of Chinese investments launched in 2009 to strengthen international news coverage and global presence, Xi’s directives to pursue innovative external propaganda have led China’s external communication efforts to unprecedented levels of assertiveness and ambition. Leveraging advancements in information technology and bolstered by the nation’s growing confidence in its national power, these efforts signify a significant evolution in China’s approach to global propaganda on Tibet.

Rebranding Tibet as ‘Xizang’

The latest development in the propaganda strategy is the attempt to impose the Chinese term “Xizang” in place of “Tibet” to the international community. Capitalizing on the turmoil caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, China quietly and strategically introduced a new policy around fall 2021. Amid the pandemic, the Chinese party-state aimed to eliminate Tibet’s name from global discourse, with the sinister objective to replace it with the Sinified term “Xizang.” Over the past two years, since the policy’s discreet inception, it has become evident that China’s propaganda attempts to erase the name “Tibet” are being systematically, gradually and incrementally implemented on the global stage. This effort is part of China’s external propaganda strategy to present a favorable narrative of the country under the theme to “tell a good Chinese story.”

China employs a strategic linguistic approach aimed at substituting the term “Tibet” with “Xizang,” a Sinified term, in order to reduce the international recognition of Tibet as a distinct entity. This policy, introduced during the midst of the global COVID-19 pandemic in fall 2021 by the Chinese Communist Party Propaganda Department, was quietly implemented without significant public attention.[7] Reflecting on the two years since its launch, it is evident that the rebranding strategy of Tibet as Xizang is gradual, deliberate and incremental.

The initial introduction of propaganda portraying Tibet as Xizang can be traced to the tabloid Global Times, owned by the state media organization People’s Daily.[8] In recent times, Xinhua and People’s Daily have started using it. Even when the term Tibet is utilized, these Chinese state media entities are sure to append “China’s Tibet” to emphasize their preferred propaganda phrase.[9]

The intermittent use of the term “China’s Tibet” is expected to persist in the short to medium term, eventually transitioning gradually toward China’s preferred propaganda term “Xizang” in the long run. Recognizing Tibet as a widely recognized global name, the Chinese party-state anticipates that its external propaganda strategy for Tibet will require time to succeed. Paradoxically, despite its intent and available resources, the Chinese party-state faces the challenge of imprinting its preferred term when very few outside China are familiar with the term Xizang. China’s past efforts in rebranding Tibet as Xizang had failed, but the current unfolding strategy seems to be more confident and better planned than in the past.

Propaganda forums on Tibet

The concerted effort to officially and internationally promote the term Xizang gained momentum in 2023. Initially the push unfolded gradually through state or party-affiliated media channels and external propagandists aiming to normalize “Xizang” usage.

One particularly prominent platform for this propaganda was the 7th Forum on the Development of Tibet, which reconvened on May 23, 2023, after a hiatus since 2019 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The forum’s title and theme reveal its propagandistic nature. Officially titled “2023 Forum on the Development of Xizang, China: New Era, New Xizang, New Journey–New Chapter in Xizang’s High-Quality Development and Human Rights Protection,” the forum marked a deliberate attempt to replace the internationally recognized name “Tibet” with “Xizang” in English-language discourse.[10] This strategic shift is evident when compared to the titles of the previous six forums, which were all titled “Forum on the Development of Tibet, China.”

| YEAR | LOCATION | DATE | OFFICIAL TITLE |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | Vienna | Nov. 29, 2007 | First Forum on Development of Tibet, China |

| 2009 | Rome | Oct. 22, 2009 | Second Forum on Development of Tibet, China |

| 2011 | Athens | Nov. 10, 2011 | Third Forum on Development of Tibet, China |

| 2014 | Lhasa | Aug. 12-13, 2014 | Forum on Development of Tibet, China |

| 2016 | Lhasa | July 7-8, 2016 | Forum on Development of Tibet, China |

| 2019 | Lhasa | June 14, 2019 | Forum on Development of Tibet, China |

| 2023 | Beijing | May 23, 2023 | 2023 Forum on the Development of Xizang, China |

The pivotal moment arrived in October 2023 when China began to officially use “Xizang” for Tibet in the English rendition of Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s remarks during the third “Trans-Himalaya Forum for International Cooperation” held in Tibet.[11] Notably the event saw the participation of officials from over a dozen countries, several of which share borders with Tibet. All reference to Tibet in his opening speech at the forum on Oct. 5 was given as “Xizang,” including calling the Qinghai-Tibet plateau the “Qinghai-Xizang plateau.” This rendition of Wang’s speech adds weight to his pronouncement of the external orientation of China’s propaganda work to Sinify Tibet’s global image and erase the internationally recognized term “Tibet” in diplomatic discourse.

In the 2023 edition of China’s 7th “Forum on Development,” the term “Xizang” replaced “Tibet,” marking a shift toward the Chinese government’s Sinified name for the country. The 2019 forum still used the internationally recognized name “Tibet.”

The orchestration of such events falls under the purview of the State Council Information Office (SCIO), also known as the CCP Central Office of Foreign Propaganda, an institution established in 1991 with the primary aim of countering international backlash following the Tiananmen Square Massacre in 1989.

SCIO has remained consistently engaged in propagating the Chinese narrative on Tibet. It orchestrated a series of ‘Forums on the Development of Tibet,’ with the first event in the series held in the Austrian capital of Vienna in 2007. The second was held in the Italian capital Rome in 2009, and the third was held in the Greek capital of Athens in 2011. Since the fourth forum, which was held in the Tibetan capital Lhasa in 2014 (the fifth and sixth were also in Lhasa in 2016 and 2019, the seventh in Beijing in 2023), the Tibet Autonomous Region has also been named as a co-organizer. This could be a deliberate move to lend official credence to the TAR’s government, aligning its participation with the overarching narrative orchestrated by Beijing. Incidentally, the seventh forum held in May 2023 had “Xizang” replacing Tibet in the English version of documents.

Propaganda through conferences

Multiple conferences with an international orientation were also orchestrated throughout 2023 in addition to the above-mentioned forum. One such event was the “7th Beijing International Tibetology Symposium,” themed “Prosperity and Development of Tibetology and an Open Tibet,” held on August 14, which sought to manipulate academic platforms for political agendas to push China’s narrative for the foreign audience.[12]

Presented as a scholarly exchange co-hosted by United Front entities, including the China Association for the Preservation and Development of Tibetan Culture, the conference underscored China’s tight control over academic dialogue and genuine mutual learning. It served to legitimize the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) approach in Tibet and promoted a state-centric narrative on Tibet. Activities and awards for “Research on the Relationship between Tibet and the Central Government since the Yuan Dynasty (Volume 1 and 2)” exemplified this effort to push forward historical propaganda.

Through the format of an interview to Chinese state media, Li Decheng, deputy director-general of the China Tibetology Research Center, further advanced the state narrative on Tibetan Buddhism’s reincarnation practice. On Aug. 16, 2023, during the 7th Beijing International Symposium on Tibetology, Li launched a pointed attack on the 14th Dalai Lama, asserting that the recognition of the Dalai Lamas is the prerogative of the Chinese government and not the 14th Dalai Lama himself. According to Li, religious affairs are part of Chinese state affairs, and the management of religious affairs should be in accordance with state-promulgated laws.[13]

An editorial published in the United Front News WeChat account soon after the symposium reinforced China’s strategy of dominance in Tibetology, touting its achievement in suppressing Tibetology in Western academia. The editorial framed academic progress as a competition between China and the West on Tibet. Oversimplifying the multifaceted nature of Tibetology and dismissing critical scholarly work, it alleged that Western scholars have ulterior motives in their research efforts to control the narrative on Tibetology and the pursuit of truth.

The Chinese party-state also convened a first “Tibet Chinese National Community Awareness Forum” at the InterContinental Lhasa Paradise, owned by the InterContinental Hotels and Resorts group, in Lhasa on Sept. 18, 2023.[14] The forum, whose theme was “Creating the Soul of China and Co-Creating a Model District,” brought together a total of 420 delegates, primarily Chinese academics, from all over China to share ideas to “better strengthen national unity and safeguard the reunification of the motherland in Tibet.”[15] State media highlighted numerous Chinese academics specializing in supplying ethnic policy ideas toward creating a Chinese nation.

Discrediting the Dalai Lama

For many around the world, Tibet and the Dalai Lama are inseparable. Almost three decades ago, the Chinese party-state made a deliberate decision to target the Dalai Lama. In July 1994, during the CCP’s Third National Forum on Work in Tibet held in Beijing, a vehement campaign against the Dalai Lama was initiated. Party documents, using aggressive and crude language, likened the Tibet issue to a serpent, with the Dalai Lama portrayed as its head. According to these documents, “The focal point in our region’s fight to oppose splittism is to oppose the Dalai clique. As the saying goes, to kill a serpent, we must first cut off its head. If we don’t do that, we cannot succeed in the struggle against splittism.”[16]

This aggressive campaign against the Dalai Lama, launched in 1994, persists to this day. In Tibet, the party has prohibited Tibetans from displaying his photograph, routinely condemns the Dalai Lama during party meetings and mandates that Tibetan job applicants express no affinity toward him.

On the global stage, the Chinese party-state, in its external propaganda, frequently refers to the Dalai Lama as a “wolf in sheep’s clothing,” a puppet of the CIA, a former serf master or even a demon. While the global community widely admires the Dalai Lama for his efforts in promoting peace and human unity, the CCP has incessantly pursued its campaign over the years to discredit and vilify him, aiming to neutralize the Tibet issue.

The CCP policy to discredit the Dalai Lama persists. In April 2023, leveraging the susceptibility of global media to sensationalism, shadow propagandists from China orchestrated a smear campaign against the Dalai Lama. They distorted an innocent interaction between the Dalai Lama and an Indian boy at a public event, falsely framing it as an act of pedophilia.[17] By editing and manipulating an official video recording of the public gathering, these propagandists fabricated and disseminated a narrative depicting the Dalai Lama as a pedophile.

The Chinese authorities took further leverage of global media reports on the distorted projection of the Dalai Lama with the boy for propaganda against the Dalai Lama for the Chinese audience. Writing under the name of the “Human Rights Research Institute of Southwest University of Political Science and Law” to gain credibility, the domestic audience was provided a compilation of negative reports carried by global media against the Dalai Lama.[18] The report carries offensive and defensive arguments over the incident to drive home the Chinese Communist Party’s propaganda goal of demonizing the Dalai Lama.

Misusing modern technology for information control

The Chinese government extensively employs censorship and information manipulation to suppress critical information regarding Tibet’s political situation, human rights violations and cultural suppression. It utilizes modern information technology not to address societal issues but rather for censorship and surveillance purposes.

Contrary to the optimistic view of modern information technology as a solution to human problems, the Chinese government has embraced these advancements for controlling information and surveillance. The CCP’s utilization of information technology for repression is extensively documented. As global technological advancements move toward artificial intelligence in 2024, there’s little doubt that the Chinese government will harness this technology to further suppress dissent under the guise of “innovative management.”

The Chinese government has tightened its control over the flow of firsthand accounts from Tibet by imposing stricter border controls to prevent Tibetans from sharing their experiences of CCP governance.

The year 2008 marked a significant shift in controlling the exodus of Tibetan refugees. Beijing’s focus on bolstering its international image shifted gears after the successful staging of the Summer Olympics. In the months preceding the Olympics, widespread uprisings against Chinese governance erupted in Tibet.[19] In response to these events and in alignment with its strategy to enhance China’s global image following the Olympics, the Chinese party-state initiated various measures to stem the outflow of Tibetans.

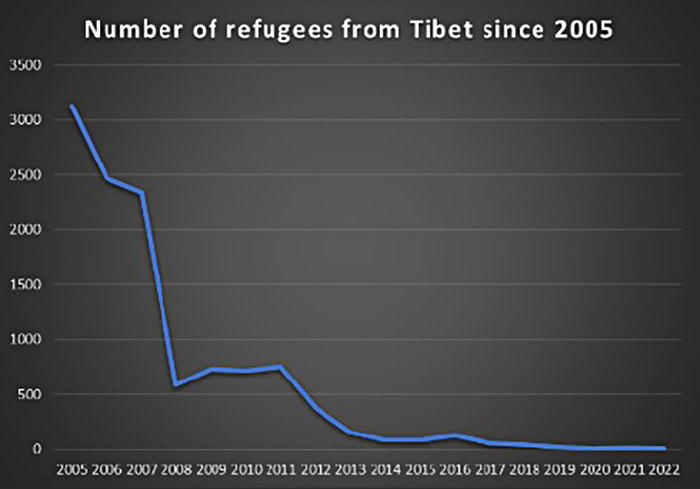

The annual average of approximately 2,500 Tibetan refugees escaping through the mountains saw a notable decline in 2008. While 2,338 Tibetan refugees crossed the border in 2007, this number plummeted by 75% in 2008, with only 588 making the journey. This policy aimed at halting the flight of Tibetan refugees has seen remarkable success, with a sharp decline to merely five arrivals in 2022. The Chinese government’s stringent measures have yielded near-perfect success in stemming the flow of Tibetan refugees and their narratives.

By turning Tibet into a highly securitized enclave and effectively curtailing the flow of firsthand accounts from the region, the Chinese party-state hopes it has successfully cleared obstacles to amplify its external propaganda on Tibet.

| YEAR | NUMBER OF REFUGEES | % CHANGE RELATIVE TO 2007 |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 3,129 | |

| 2006 | 2,472 | |

| 2007 | 2,338 | |

| 2008 | 588 | -74.9% |

| 2009 | 737 | -68.5% |

| 2010 | 723 | -69.1% |

| 2011 | 753 | -67.8% |

| 2012 | 375 | -84.0% |

| 2013 | 156 | -93.3% |

| 2014 | 88 | -96.2% |

| 2015 | 88 | -96.2% |

| 2016 | 129 | -94.5% |

| 2017 | 52 | -97.8% |

| 2018 | 43 | -98.2% |

| 2019 | 19 | -99.2% |

| 2020 | 5 | -99.8% |

| 2021 | 10 | -99.6% |

| 2022 | 5 | -99.8% |

Number of refugees from Tibet since 2005. (Data source: Central Tibetan Administration)

Propaganda tactics: Vetted foreign media tour

China’s stringent control over access to Tibet remains extensively documented, and journalists are particular targets of this strategy.[20] Journalists, only a select few, are only provided access after being meticulously vetted to align with the Chinese Communist Party’s narrative, and they constitute the exclusive group permitted entry through state-organized and managed tours. This carefully curated access serves a dual purpose: to counter international criticisms and to craft a favorable image of Chinese governance, positioning it as a model for the global community.[21] China has persistently sought to influence countries in the Global South, advocating for its vision of “people-centered” development and the concept of “harmonious development between human beings and nature.”

An illustrative example of this orchestrated narrative presentation was the program by the China International Press Exchange Center for some 30 journalists in Tibet. From Oct. 3 to 8, 2023 they facilitated the visit of these journalists from 20 countries to Nyingtri and Lhasa in Tibet, as part of “telling the real story of Tibet.”[22] Notably, the journalists were from countries such as Pakistan, Nepal, Belarus, Ethiopia, Chile, Vanuatu, Timor-Leste, Malaysia, Kyrgyzstan, and Georgia—predominantly underdeveloped or developing nations, often sharing similar political ideologies, and frequently recipients of Chinese aid and loans.

Echoing China’s propaganda: diplomatic tours and state-controlled narratives

China is known to be leveraging its diplomatic channels and economic influence to exert pressure on international organizations, governments and corporations to conform to its prescribed narrative on Tibet. Utilizing its position as a global power, the Chinese government orchestrates tours to Tibet for selected foreign diplomats, primarily from developing countries, to amplify its external propaganda on Tibet. These carefully curated tours showcase a sanitized version of Tibet, devoid of the stark realities of human rights abuses, cultural suppression and environmental degradation.

In August and September 2023, a delegation of 11 Geneva-based foreign diplomats from developing countries, including Venezuela, Cuba, Nicaragua, Pakistan and Belarus, visited Tibet at the invitation of China’s Foreign Ministry. Ambassador Khalil Hashemi, the permanent representative of Pakistan (he has since been appointed as the Pakistani Ambassador to China), led the group.[23]

During their visit, the diplomats were met by Yan Jinhai, deputy secretary of the Party Committee and chairman of the Tibet Autonomous Region. Chinese state media reported that Yan extolled Tibet’s “achievements” in economic development, living standards, national unity, cultural preservation and ecological efforts under the leadership of the CCP.

Despite the international community’s persistent concerns about the human rights situation in Tibet, the delegation ignored these issues and instead echoed the CCP’s propaganda.

A similar group of foreign diplomats, primarily from developing countries, was taken on a tour of Tibet in May 2023, just before the forum on the development of Tibet. Chinese state media extensively quoted these delegates, presenting their glowing affirmations as validation of Beijing’s narrative on Tibet.[24]

For instance, the ambassador of the Philippines to China praised China for ensuring that “local [Tibetan] students can learn new things, but also while preserving their own culture, their own language.”

Similarly, the ambassador of Nepal to China lauded China’s Belt and Road Initiative for promoting connectivity and enterprise structural development.

Both these ambassadors echoed Chinese propaganda at the expense of the reality of the situation in Tibet.

Foreign propagandists in service

Under Xi Jinping, Communist China is increasingly resorting to tactics reminiscent of its early revolutionary days. One such tactic involves cultivating an international image using foreign influencers. Historically, figures like American journalists Edgar Snow and Anna Louise Strong were instrumental in allowing the party-state to communicate the merits of the communist model to the world. In the contemporary era, where social media wields greater influence than traditional media within specific audience segments, the party-state has actively been engaged in recruiting foreign influencers to disseminate its propaganda through digital channels.

These foreign social media influencers amplify or defend the CCP’s messages to global audiences. While their impact within Tibet, particularly among Tibetans themselves, remains minimal, they serve the party’s interests by bolstering its legitimacy among Chinese citizens and by advocating for and disseminating the party’s narrative on Tibet abroad.

A recent report by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) outlines that the CCP-state has orchestrated an extensive network of international individuals who propagate its online propaganda and narratives on China, aiming to portray itself as a respectable adherent to global norms and regulations.[25] This effort includes the establishment of multilingual influencer studios, engagement with international students in Chinese universities and competitions incentivizing creators to advocate for the CCP’s perspective.

According to ASPI, Beijing has recruited over 120 international influencers willing to align their content with the CCP’s narratives, endorsing its values, policies and ideology. These influencers are instrumental in bolstering the party’s credibility among Chinese audiences and amplifying its propaganda on the global stage. Some influencers, seeking increased popularity and revenue, have discovered that aligning with Chinese nationalism through promoting CCP propaganda can expedite their success, exploiting algorithms of mainstream social media platforms that prioritize consistent and trending content. The report further highlights the prevalence of content generated by Chinese state media and foreign influencers dominating searches related to contentious topics like Tibet and Xinjiang, utilizing social media algorithms favoring frequent posting of new material.

ASPI underscores that while these influencers aren’t directly instructed by state media, they are motivated by rewards, inducements and limitations. The report cautions that the proliferation of foreign influencers advocating for the CCP will complicate the discernment between genuine, factual content and propagandistic material, posing challenges for social media platforms, foreign governments and individuals seeking to distinguish between the two.

Examining the content shared by foreign influencers on the topic of Tibet, it emerges that their primary goal is to defend the Chinese government against worldwide criticisms, while presenting themselves as neutral and independent observers or “journalists” unaffiliated with China.

Screenshots of a sample of collected postings below serve as compelling evidence of the agenda of the foreign influencers. Their strategic dissemination includes promoting the contentious replacement of the universally recognized name “Tibet” with the Chinese-imposed term “Xizang,” aligning with China’s persistent endeavor to control the narrative surrounding Tibet. They advocate for China’s boarding schools designed for Tibetan children, positioning these institutions as progressive avenues for education and socio-cultural integration.

They staunchly amplify China’s specific political narratives, particularly emphasizing and justifying the Chinese government’s stances on pre-1959 Tibetan governance and societal structures. A notable aspect of their dissemination involves echoing the state’s portrayal of Tibetans, often presenting them in a perpetual state of joyfulness, frequently depicted engaging in traditional dances, while endorsing China’s “ethnic minority policy” as a model of “inclusive” governance.

Furthermore, they actively participate in smear campaigns targeting the Dalai Lama, leveraging manipulated video clips from public events to malign him. They also echo the Chinese party-state’s depiction of Tibetans as a community stuck in a backward cultural paradigm, citing their nomadic and herding practices as detrimental to the environment. Paradoxically, they advocate for China’s “Green China” initiatives, arguing for the displacement of herders while defending China’s polluting factories as essential economic engines.

Additionally, they echo China’s narrative of ushering modernization and economic progress into Tibet, predominantly highlighting the expansion of the railway network and the surge in tourism without questioning the negative impacts of these on Tibet and Tibetans, which include whether or not they come at the cost of eroding the unique cultural identity and sustainable practices of the Tibetan people.

China-resident Canadian youtuber Daniel Dumbrill, accompanied by China Global Television Network’s Li Jingjing, amplifies China’s propaganda on its school system in Tibet at Sakya Middle School in August 2020, showcasing happy children.

New Zealander Andy Boreham promotes his video amplifying China’s propaganda on the “56 ethnic groups.” The Chinese government categorizes Tibetans as one of its “ethnic minority groups,” contrasting the view of Tibetans as a people under foreign subjugation.

American Jason Smith impresses his handlers by staying informed about Xizang replacing Tibet but overlooks Chinese dominance on Tibetan signs.

Jason Smith amplifies Chinese propaganda on Tibet name replacement with the Sinified term Xizang. Smith shares Chinese propaganda social media content defending China’s policy move with images of Tibetan riders carrying a Chinese flag in a staged horse race festival.

Americans Shaun Rein and David Blair strolling through a market with their Chinese state-media host, Miao Xiaojuan of Xinhua, promoting China’s economic policies in Tibet.

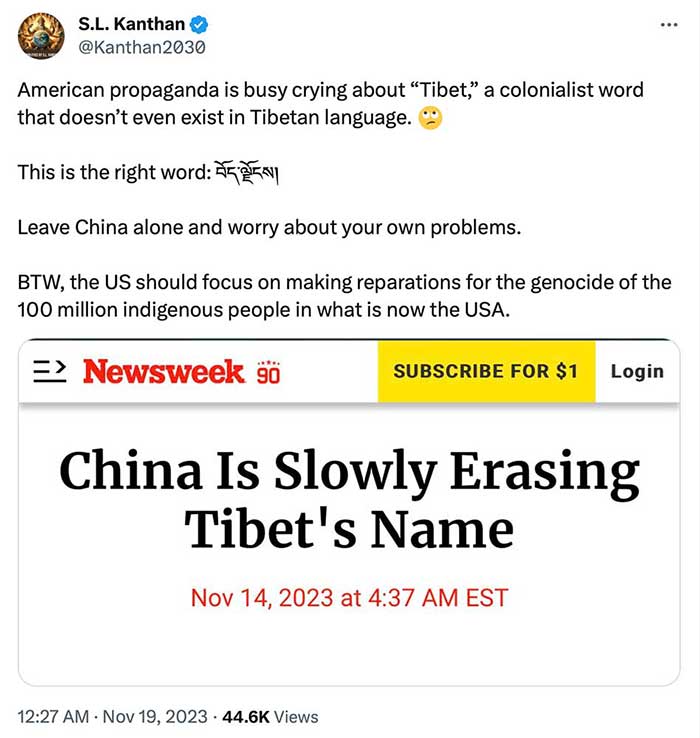

Indian social media influencer S.L. Kanthan amplifying China’s propaganda on “modern Tibet,” drawing comparisons with India’s approach.

S.L. Kanthan echoing the Chinese government talking point that Tibet is a colonialist term, even though the term’s genesis came long before Westerners set foot in Tibet.

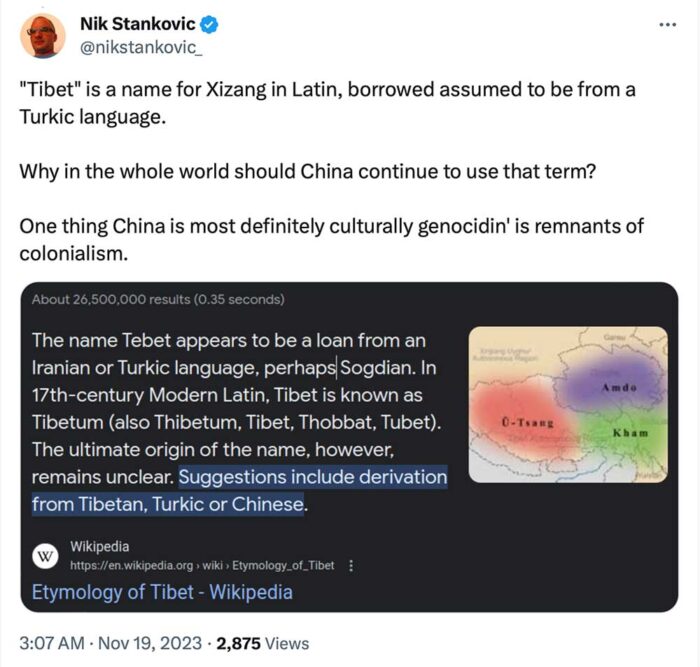

Serbian Nik Stankovic unwittingly contradicts his comrade S.L. Kanthan’s assertion that “Tibet” is a Western colonialist term. Stankovic defends China’s replacement of “Tibet” with “Xizang,” implying that China is reclaiming ownership from the West. However, in reality, “Xizang” itself is a term stemming from Chinese colonialism.

Italian vlogger Rachele Longhi in a Tibetan circle dance promoting China’s propaganda on Tibetans as perpetually dancing happy people.

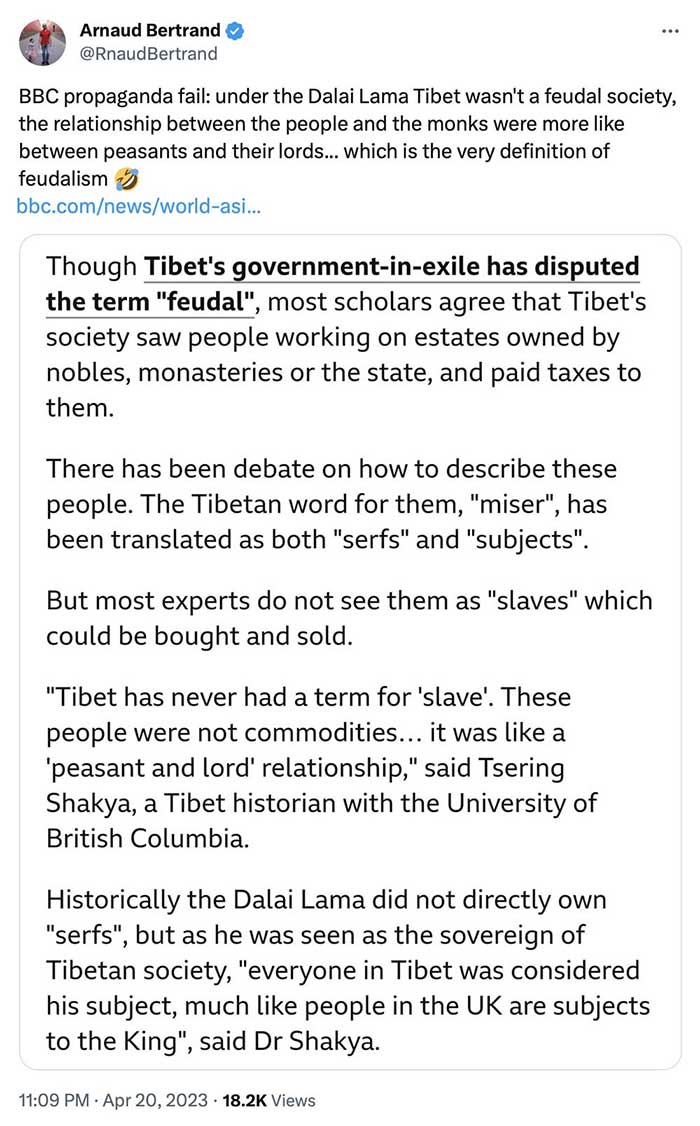

French Arnaud Bertrand defends China’s portrayal of Tibet under Dalai Lama rule as a feudal society.

Outreach through Tibetans in exile

Understanding the impact of the Tibetans in exile on the international community’s approach to Tibet, Tibetans in exile were particularly discussed in the 1993 propaganda strategy conference. In his opening remarks, Zeng Jian-hui said, “We should reinforce our propaganda to Tibetans living abroad. There are hundreds of thousands of Tibetans living abroad. These people form the basis of the Dalai Clique. We should try to win them over through our propaganda and our actual work with them, so as to weaken the force of the Dalai Clique.”[26] Zeng further suggested the way to do this was “by using their feeling for their homeland.”

Accordingly, the Chinese authorities have been making efforts, including through officials of the CCP’s United Front Work Department posted in some of the Chinese embassies in Australia, Belgium, Canada, India, Nepal, Switzerland, and the United States, in wooing Tibetans in exile. A main method adopted is provide incentives for them to return to Tibet, or the offer of travel to Tibet. On Dec. 8, 2023 five returned Tibetans in Tingye (Dinggye) in western Tibet were provided with 2500 Yuan each by the county’s United Front (which issued a press release on it) for attending a symposium to discuss affairs of Tibetans who returned to the county.

Five returned Tibetans in Tingkye county with a local United Front officials who were given cash incentive of 2500 yuans for attending a symposium.

At the end of August this year, a meeting was held in Beijing on the issue of “returned Tibetans.”[27] A United Front report on the meeting claimed to have “strengthened the power of friendship” (with Tibetans in exile) and that in the past five years it has “established regular contacts with overseas Chinese in India, Nepal, Australia, the United States, Switzerland and other countries and regions where Tibetan [and] overseas Chinese live in large numbers, effectively expanding the circle of friends of the Overseas Chinese Federation.” The report further said that it has been “guiding them [Tibetans in exile] to tell the story of Tibet well, spread the voice of Tibet well.”

Indeed, 2023 saw Chinese authorities allowing a select few Tibetans from India and the West to visit their homeland, after a gap of several years. More interestingly, unlike in the past, sources say that these Tibetans experienced lesser restrictions and were in fact encouraged to speak out about their experience on their return to their respective places. According to sources, the United Front arranged for group tours by Tibetans abroad to their homeland.

Conclusion

China’s ambitious long march to bolster its international image was accelerated 15 years ago. In the period following the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics, which symbolized China’s emergence as a global power, the strategy to manage the Tibet issue on the international stage commenced by halting the exodus of Tibetan refugees from Tibet and initiating external propaganda on Tibet through China’s “big propaganda” media investments to propagate its own narrative on China’s rise and sovereignty over Tibet.

The Chinese government employed diverse methods to control the discourse surrounding Tibet, aiming to redefine its global portrayal. With confidence in its status as an economic powerhouse, China became increasingly assertive in its external propaganda, displaying meticulous planning and execution unlike its past efforts.

Amid the global preoccupation with the COVID-19 pandemic, the Chinese party-state quietly launched a renewed policy to replace the universally recognized term Tibet with the Sinified term Xizang in fall 2021. Two years into the implementation, it’s evident that the strategy to replace “Tibet” with “Xizang” is deliberate, gradual and incremental.

In 2023, China aggressively pushed this policy on the international stage through orchestrated propaganda forums on Tibet, targeting diplomats and journalists, especially from developing countries. The year also witnessed a sophisticated smear campaign against the Dalai Lama, a culmination of nearly 30 years of efforts to vilify him, projecting false accusations on a global scale.

China’s external propaganda on Tibet appears set to intensify in the coming years as part of its long-term plan to erase Tibet’s identity and discredit the Dalai Lama globally. With no end in sight to Xi Jinping’s rule and his directive to “tell a good Chinese story,” China’s external propaganda on Tibet is expected to continue incrementally.

However, the positive impact hoped for by the Chinese party-state from its external propaganda on Tibet remains doubtful. China’s image problem seems to persist from 15 years ago when it sought to alter its international image. Despite the party’s claims of victory, doubts persist within China regarding the effectiveness of its efforts. The COVID-19 pandemic and China’s lack of transparency in external propaganda have seemingly damaged China’s international image, potentially returning it to its starting point from 15 years ago.

If the situation of the Tibetan people is as good as the Chinese government claims, it should have nothing to fear in providing access to Tibet to independent observers, journalists and diplomats. If it seriously believes the people of Tibet have benefited greatly under its rule, it should allow them freedom of movement and expression so that they can travel and make this case themselves.

Footnotes:

[1] “China’s Public Relations Strategy on Tibet: Classified Documents from the Beijing Propaganda Conference” International Campaign for Tibet, 1993

[4] “Top-level meeting in Beijing sets strategy on Tibet,” International Campaign for Tibet, January 29, 2010, https://savetibet.org/top-level-meeting-in-beijing-sets-strategy-on-tibet/

[5] For China’s investment in 2009 to bolster international news coverage, see Anne-Marie Brady, “China’s Foreign Propaganda Machine | Wilson Center,” Wilson Center, October 26, 2015, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/chinas-foreign-propaganda-machine. See also L. F. Lye, “China’s Media Initiatives and Its International Image Building,” International Journal of China Studies 1 (2) : 545-568., October 2010, https://scholarbank.nus.edu.sg/handle/10635/116257.

[6] “Xi Jinping: Ideological Work Is an Extremely Important Task for the Party – High-Level Dynamics” Xinhuanet, Aug. 19, 2013, https://web.archive.org/web/20231226125131/http://www.xinhuanet.com//politics/2013-08/20/c_117021464.htm.

[7] Bill Bishop’s Sinocism may have been the first to report on China’s strategy to replace Tibet with “Xizang”. “Tibet becoming Xizang in external propaganda?” Oct. 20, 2021, https://sinocism.com/p/positive-energy-for-the-economy-xizang?utm_source=%2Fsearch%2Fxizang%2520ministry%2520of%2520propaganda&utm_medium=reader2

[8] One example is this item “Plateau photovoltaic bases pushed to achieve carbon emissions targets,” Global Times, Nov.14, 2021 https://web.archive.org/web/20231226130209/http://english.itpcas.cas.cn/new_news/202203/t20220329_303207.html

[9] The two Chinese state media outlets, Xinhua and People’s Daily, have been transitioning to the use of “Xizang” instead of “Tibet” in their reports.”

[10] “Forum on development of Xizang opens in Beijing,” CGTN, May 23, 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20231226132155/https://news.cgtn.com/news/2023-05-23/Forum-on-development-of-Xizang-opens-in-Beijing-1k2OJRz0kRa/index.html.

[11] Speech by China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi at the Third Trans-Himalaya Forum for International Cooperation, “Promoting the Harmony of Humans and Nature and Jointly Advancing Cooperation on Regional Development,” Qiushi, Oct. 5, 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20231226133153/https://subsites.chinadaily.com.cn/Qiushi/2023-10/07/c_926607.htm

[12] “Seminar on Xizang: Scholars from China and Overseas Gather for Beijing Seminar on Tibetan Studies,” CGTN, August 14, 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20231215171608/https://news.cgtn.com/news/2023-08-14/VHJhbnNjcmlwdDc0MDMz/index.html.

[13] Chao Liu and Chengchen Yang, “Why Is the Reincarnation System of Living Buddha Unique to China? _Religion_China Tibet Net,” China News Network, August 18, 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20231215171041/http://www.tibet.cn/cn/religion/202308/t20230818_7469584.html

[14] “Notes on the Opening of the First Tibet Forum on Forging Chinese National Community Consciousness: Draw Concentric Circles to Gather Positive Energy,” China Tibet News Network, September 20, 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20231226131352/http://www.xztzb.cn/news/1695174374796.shtml.

[15] “Held in Tibet for the First Time! Opening Tomorrow!,” Tibet Daily, September 18, 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20231226133758/https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/_0r3pqmWaNPL0Hzvd6J6VQ

[16] “Cutting Off the Serpent’s Head: Tightening Control in Tibet, 1994-1995,” Human Rights Watch, March 1996, https://www.hrw.org/legacy/summaries/s.china963.html.

[17] “Dalai Lama Defended over Tongue-Sucking Remark,” BBC, April 14, 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-65272213.

[18] “Summary and Analysis of International Public Opinion on the 14th Dalai Lama’s ‘Tongue Sucking’ Incident,” Institute of Human Rights, Southwest University of Political Science and Law, May 1, 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20231226134302/https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MjM5NTE1OTY2MA==&mid=2650063323&idx=1&sn=8d00bdb7e1fd66ba754663a0bc92938f&chksm=befcaad8898b23cec22a45755435a23490d9f75a44f4698f2e49eb47c094c24bfa0155c8ac93#rd.

[19] Amnesty International, “People’s Republic of China: The Olympics Countdown – Crackdown on Tibetan Protesters,” AI Index: ASA 17/070/2008 (April 2008).

[20] International Campaign for Tibet, “Access Denied: China’s Enforced Isolation of Tibet, and the Case for Reciprocity,” International Campaign for Tibet, May 7, 2018, https://savetibet.org/access-denied-chinas-enforced-isolation-of-tibet-and-the-case-for-reciprocity/.

[21] Matt Ferchen, “How China Is Reshaping International Development,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, January 8, 2020, https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/01/08/how-china-is-reshaping-international-development-pub-80703.

[22] “Telling the Real Tibet to the World – a Record of a Foreign Media Person’s Interview Trip to Tibet,” Tibet Daily, October 10, 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20231215180700/https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/68JJiRZGZcSkUa-5LIALxA

[23] “Yan Jinhai Meets with Diplomatic Delegations from Friendly Countries in Geneva,” Tibet Daily, September 1, 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20231215180400/http://e.xzxw.com/xzrb/202309/01/content_217197.html.

[24] “Unity, Civility and Modernization: Foreign Diplomats, Experts Narrate Miraculous Development in Xizang through ‘Four-Season’ Journey – Global Times,” May 24, 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20231215180103/https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202305/1291299.shtml.

[25] Fergus Ryan, Matt Knight, Daria Impiombato, “Singing from the CCP’s Songsheet” (Australian Strategic Policy Institute, November 2023), http://www.aspi.org.au/report/singing-ccps-songsheet.

[26] “China’s Public Relations Strategy on Tibet: Classified Documents from the Beijing Propaganda Conference” International Campaign for Tibet, 1993, page 56

[27] “11th National Meeting of Overseas Chinese Federation of the Tibet Autonomous Region: Broadly unite the hearts of overseas Chinese and unite and forge ahead to promote the long-term security and high-quality development of Tibet,” United Front, August 28, 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20231218013449/https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/74G_RnRwSaYfm6ASXyUjfg