Two months ago, on Feb. 14, over 100 Tibetans gathered at the local government office in Derge (Chinese: Dege) county, Kardze (Ganzi) Tibet Autonomous Prefecture in Sichuan to peacefully express their opposition to the planned Kamtok (Gangtuo) hydropower project that will submerge and affect at least two villages and six monasteries.[1] In video footage of subsequent protests at Yena (Yinnan) monastery, Tibetans can be seen begging local officials to reconsider the construction of the dam. News of at least several hundred arrests and injured protesters soon followed. Now, two months later, it is unclear how many individuals remain detained.

Despite a large majority of detainees reportedly released, at least two high profile protesters, Tenzin Sangpo (the senior administrator of Wontoe (Wangdui) monastery) and Tenzin (a village official) remain in detention.

Protestors at Yena monastery pleading with visiting local officials on 20 February 2024 (Source: Radio Free Asia)

The Derge protests are significant because there was a coordinated effort to record the peaceful opposition and disseminate protest footage. Despite the high risk of imprisonment, physical abuse and torture, surveillance, a communication blackout and house raids among other restrictions on basic rights, local Tibetans successfully alerted the international community to what is at stake in their historic home: the loss of ancient and active Buddhist cultural sites, connection to land and community, the erasure of their place in Tibet, and the absence of any representation or avenues to address concerns.

The Driru county (Nagqu prefecture, Tibet Autonomous Region) protests that erupted in 2010 and escalated in 2013 remind us of the long-term costs of defiantly resisting the destruction of one’s homeland. After about 3,500 villagers in Driru gathered to protest illegal mining on their sacred mountain, local government officials deployed armed security forces, launched a political re-education campaign, forcibly shut down three monasteries and arbitrarily detained at least 47 individuals.[2] Three Tibetans died in custody, and the well-being of others remains uncertain since strict information controls were deployed to prevent news from spreading. Even now, 11 years later, Driru remains closed off to foreign officials and in an information black hole.

Derge spotlights China’s ambitious west to east power transmission project

The Kamtok dam on the Drichu river straddles Jomda (Jiangda) County, Chamdo prefecture in the Tibet Autonomous Region in the west and Derge county, Kardze TAP, Sichuan province in the east. The 1.1 gigawatt hydropower dam, which was first approved in 2012 by the National Development and Reform Commission, will reportedly submerge six monasteries and force the relocation of two villages: Wontoe (Wangdui) village and Shiba (Xiba) in Derge, Sichuan. The six monasteries include Rabten, Gonsar and Tashi monasteries in Chamdo, TAR, and Wontoe, Yena and Khardo monasteries in Derge, Sichuan.[3]

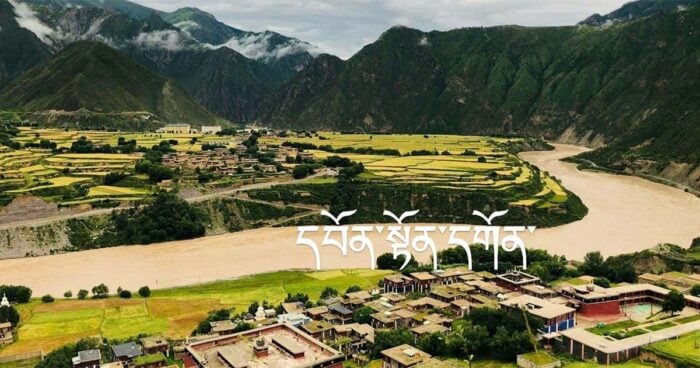

View from above Wontoe monastery, Wontoe village, Wangbuding township, Derge county, Sichuan (Source: Namgyal Choegyal)

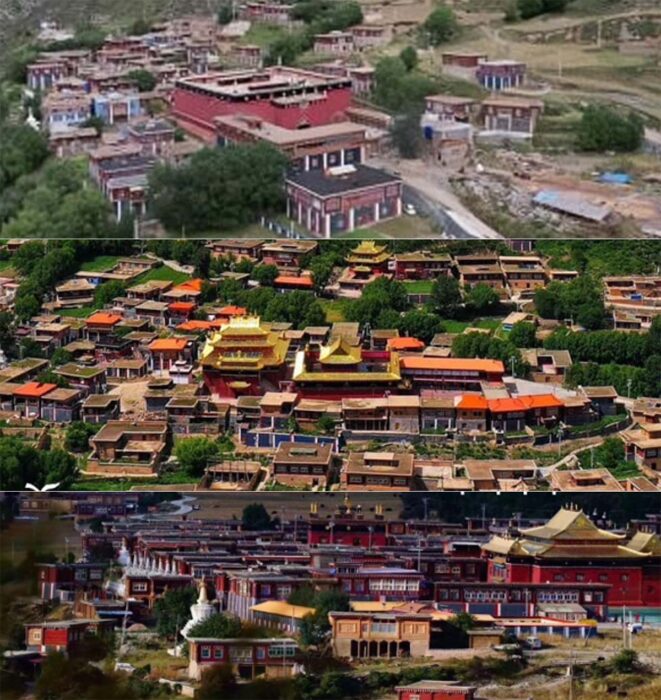

Wontoe monastery, Yena monastery and Khardo monastery in Wangbuding township, Derge county, Sichuan.

While the imminent loss of historic and active cultural sites and communities is alarming, the Kamtok dam is not a unique case. Derge protesters represent only some of the hundreds of thousands of Tibetans whose lives are being uprooted and lands are being transformed to achieve China’s ambitious and exploitative agenda to build a hydropower network across Tibet to power central and eastern China. In fact, despite strategic efforts by the state government to suppress announcements of dam construction plans, Derge has raised the alarm on the return of hydropower projects.

News of more relocations will become commonplace, as was recently observed in reports from Yangqu dam in Tsolho (Hainan) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Qinghai, where 15,555 people[4] will be relocated and the 19th century Atsok Gon Dechen Choekhorling monastery will be destroyed.[5] It is notable, however, that other sites of displacement can garner less attention because they occur in sparsely populated areas where local communities are not as politically organized. For example, Yebatan, Lawa and Suwalong hydropower dams, located downstream from Kamtok dam, will expel 644; 1,335; and 1,462 people respectively.[6] They have however attracted less organized resistance.

An obvious and serious problem is Tibetans’ lack of any method to ensure they are consulted and have meaningful influence in how actions directly affecting their ancestral lands, livelihoods and communities are taken. Even more significant, international law and basic ethical standards are clear that imprisonment, torture and collective punishment are unacceptable responses to a people raising concerns about the survival of communities, cultural sites and the environment.

Tibet’s hydropower dams to feed west to east power transmission project

At a regional level, the Kamtok hydropower dam is the first of eight cascading dams planned for the middle reaches of the Drichu (Jinsha) river. The Drichu river is recognized as China’s largest hydropower base,[7] followed by the other tributaries of the Yangtze River, Nyagchu (Yalong) River and Gyarong Ngulchu (Dadu) river.

Kamtok hydropower station is amongst at least 150 hydroelectric dams currently planned or under construction across the Tibetan Plateau. An International Campaign for Tibet analysis of over 200 hydropower dams in Tibet has found over 40 dams planned, under construction or completed in the last five years that have relocation orders ranging from 122 residents[8] to 10,000 residents.[9] On the Drichu River alone, five dams on average will relocate 2,836 people each, a total of 14,184 people.[10] This is a conservative figure, as Qinghai province alone announced in 2009 that it will relocate 120,000 residents in the upper reaches of the Yellow River by 2030.[11]

Hydropower dams are increasingly justified to meet rising energy demand, expand energy sources and capitalise on new advances in dam-building technologies that enable construction in high-risk locations. The plan is to turn Tibet into an energy exporter, initially powering central and eastern China under the west-to-east power transmission project,[12] and later neighbouring countries.

Hydropower: Puncturing the renewable myth

Although there is global consensus that investment in renewable energy must be accelerated to reduce the impacts of climate change, hydropower dams carry inherent, serious risks for the local environment and residents. Hydropower dams are susceptible to and increase the risk of earthquakes, landslides and flash floods, especially in these active seismic regions. Hydro projects are not environmentally friendly. They increase the human footprint in remote, fragile and biodiverse ecosystems and also interrupt aquatic life, soil and nutrient flows downstream. Importantly, increasing scientific study is also challenging the validity of hydropower as a realistic pathway to reducing emissions within the time period necessary to meaningfully impact global temperature targets. This significantly undermines the Chinese government’s claim that hydropower in Tibet is “essential.”[13] Dams also cause the expulsion of residents from their traditional homes. Residents are often forced to leave or coerced into it without consultation, and the displaced are provided with inadequate compensation or access to a fair process for seeking remedy to damages incurred. In fact, back in 2004, Premier Wen Jiabao suspended plans to build a cascade of 13 dams on the free-flowing Salween (Tibetan: Yuchu, Chinese: Nu) river, as well as the controversial Tiger Leaping Gorge dam, on the middle reaches of the Drichu (Chinese: Jinsha) river, citing environmental and social reasons.[14] This moratorium was later overturned in 2011 in what has been described as an effort to respond to “low-carbon” energy needs.[15]

Derge highlights state government disregard for unique Tibetan culture

While Derge is not unique as a target of hydropower dam construction, it offers insights into how little ancient, preserved and living Tibetan culture is valued by the People’s Republic of China. It is precisely because Tibetans value their cultural and religious history, community and the environment that the resistance to the Kamtok dam is particularly impassioned. The dam will submerge six monasteries. From available information, at least two of the six historic monasteries survived the violent destruction of the Cultural Revolution: Wontoe monastery and Yena monastery. Wontoe monastery[16] is of particular concern because it houses sacred Buddhist murals that date back to the 14th century whose provenance, according to oral history, dates to the 8th century. Tsering Woeser, the prominent Tibetan writer and poet, has written about the urgent need to protect these monasteries and murals, noting:

Wontoe and Yena Monasteries belong to the Sakya sect of Tibetan Buddhism, and they have a long history and survived the “Cultural Revolution.” A group of murals from the 14th to 15th centuries are considered “one of the most important Tibetan Buddhist murals discovered locally so far, and have high reference value for the study of Tibetan painting art.”[17]

Sacred murals of Wontoe monastery (Source: High Peaks Pure Earth, 5 March 2024).

However, it is not just these murals that are of importance. Monasteries are centres of learning, of community and connection. Monasteries are also where a region’s history and written knowledge are stored. They cannot be simply relocated, as their sacredness is connected to place when they are empowered or imbued with value as major events or historical figures leave an imprint. Equally, major structures cannot be easily transported. The International Campaign for Tibet has acquired a list of sacred objects housed in three (Wontoe, Yena and Khardo (Kangduo) monasteries) of the six monasteries that will be submerged (Appendix A). Objects include irreplaceable items such as a boulder with footprints of the 2nd Karmapa (Karmapa Pakshi), which date back to the 13th century, and large statues and structures that cannot be easily removed.

The pain and frustration of local residents and monks are captured in video footage where an elderly monk, reportedly from Yena monastery, can be heard pleading with local officials. He exclaims:

We didn’t do anything against the Chinese. We didn’t break the law. We followed their rules, why do we have to leave our own home? The monastery was our home for generations, it is our home today. Why are you giving trouble to these peaceful people? Why are you guys doing this? What is the reason you people are beating us? – elderly monk, footage dated 21 February 2024, Radio Free Asia.[18]

Transparency of plans and mechanisms for consultation

Dam construction plans, environmental impact assessments and mechanisms for consultation have been opaque. Following the approval of the dam in 2012, residents reportedly issued an appeal against the forced relocations that would result from the dam’s construction, stating the government had deceptively promised it would not move forward with the project unless more than 80 percent of locals agreed.[19] There is no evidence this consent was ever given. And while a feasibility assessment was completed, no environmental impact assessment has been reported.

Since 2022, preparatory activities at the Kamtok dam site have accelerated. In March 2022, a public notice issued by the legal and security bodies of the Derge county (the people’s court, people’s procuratorate, public security bureau and judicial office) warned against public gatherings, demonstrations and obstructions of official work and set out sentence lengths of 5-10 years for protest organizers and five years for participants (See attachment B). Several high-profile government officials, such as the deputy head of the Kardze Prefecture,[20] party secretary of Derge county,[21] deputy head of the county government, the County Water Conservancy Bureau and the Preparatory Office of Gangtuo Hydropower Station Construction Company, have also conducted visits assessing the preliminary work and warning against disruptive activities such as resistance to dislocation.[22]

It is worth underscoring that expulsion and land expropriation for urban development is a key driver of China’s economic growth. According to the China Family Panel Studies, a nationally representative longitudinal survey, at least 30% of households have had at least some of their land expropriated by 2018.[23] While there has been pushback, cases of successful resistance are rare, if at all, temporary. For example, in 2006, civil society concerns about environmental damage and forced displacement related to the planned Tiger Leaping Gorge dam on the lower reaches of the Drichu river in Yunnan resulted in its temporary suspension.[24] However in 2013, the dam was revived under a new name (Longpan) and half the size. While Chinese citizens can have more room for negotiation and bargaining, such privileges are rarely extended to Tibetans like the Derge protesters, who even waved PRC flags when protesting to prevent their concerns being conflated with and dismissed as “splittist” activities. Under the current political landscape, characterized by a single-minded push for ostensibly sustainable hydropower[25] and the absolute absence of a civil society sector under Xi Jinping’s rule, prospects for even a modicum of representation, healthy debate and sustainable development are grim.

Recommendations

We urge the international community, multilateral institutions, governments and parliaments to:

- Urgently raise the issue with Chinese authorities seeking information about events in Derge since 14 February from Chinese counterparts and press China to:

- Recognise and uphold the rights to freedom of expression, assembly, and association to ensure that Tibetans and others can engage in peaceful activities and raise concerns and criticisms, including government relocation and rehousing policies and practices

- Protect the right to free, prior and informed consent, right to a cultural life and the right to enjoy effective access to judicial and administrative proceedings, including redress and remedy

- Call for the immediate and unconditional release of all Tibetans still detained solely for peacefully exercising their human rights. For those individuals who remain in detention, press for individual rights to access a lawyer, to know their charge and the evidence against them, and receive visitors and appropriate medical care, if needed

- Urge China to:

- Improve transparency of dam construction plans and their progress through the approval process

- Create an institutionalised process for conducting community consultations where grievances can be aired and issues resolved, including relating to compensation for land expropriation and relocation, as well as, ultimately, access to an independent judiciary

- Immediately request meaningful and unfettered access to Tibet to assess the human rights situation on the ground, including to Derge county, detention facilities and affected monasteries in the area

Supplementary information:

- Sacred objects of Wontoe monastery, Yena monastery, and Khardo monastery

- Copy of original document and translation of “Notice on lawfully handling illegal and criminal acts of assembling crowds to disrupt social order” issued on 7 March 2022, by the People’s Court of Derge County, the People’s Procuratorate of Derge County, the Public Security Bureau of Derge County and the Judicial Office of Derge County

Footnotes:

[1] Radio Free Asia (RFA) Tibetan. (2024, February 15). Tibetans protest forced resettlement due to Chinese dam project. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/tibet/dam-project-02152024172629.html.

[2] Tibet Watch. (2014). Driru County: The New Hub of Tibetan Resistance.

[3] RFA Tibetan. (2024, February 26). Exclusive: More than 100 Tibetans arrested over dam protest. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/tibet/arrests-02222024144627.html

[4] 中华人民共和国国家发展和改革委员会 (National Development and Reform Commission, People’s Republic of China). (2021). 国家发展改革委关于青海黄河羊曲水电站: 项目核准的批复 (National Development and Reform Commission on Qinghai Yellow River Yangqu Hydropower Station: Project approval reply). https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/zcfb/pifu/202112/t20211209_1316577.html?state=123&state=123.

[5] RFA. (12 April 2024). Historic Tibetan Buddhist monastery is being moved to make way for dam. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/tibet/monastery-dam-04122024160515.html.

[6] Yebatan (叶巴滩) and Lawa (拉哇) hydropower dams are downstream from Kamtok dam. Yebatan has already relocated 644 people and the Lawa project will relocate 1,335 people. Details on the Yebatan relocation figures are no longer available, as articles on Chinese websites often expire. However, information was previously available at https://www.gzz.gov.cn/gzzrmzf/c101413/202207/f2723eeb0418463bbc6677f4be390f2c.shtml, accessed in September 2023. The Lawa hydropower project will relocate 1,335 people. See 北极星水利发电网(Polaris Hydropower Grid). (15 January 2019). 总投资309.69亿元!国家发展改革委关于金沙江拉哇水电站项目核准的批复’ (The total investment is 30,969 billion yuan! Approval of the Jinsha River Lawa Hydropower station project from the National Development and Reform Commission). https://news.bjx.com.cn/html/20190115/956665.shtml.

[7] 新闻中心 (Sina news). (3 August 2017). 世界第二大水电站开建 金沙江27级水电雏形初现’ (Construction of the world’s second largest hydropower station begins, and the prototype of the 27-level hydropower stations on the Jinsha River begins to emerge). https://news.sina.com.cn/o/2017-08-03/doc-ifyitayr8830868.shtml.

[8] T西藏自治区住房和城乡建设厅 (Department of Housing and Urban-rural Development of the Tibet Autonomous Region). (8 September 2021). 西藏玉曲河扎拉水电站迁移人口安置独立评估招标公告’ (Tender announcement for the Independent Assessment of Resettlement of the Resettled Population at the Yuqu River Zala Hydropower Station in Tibet). http://zjt.xizang.gov.cn/xwzx/zbgg/202109/t20210908_259884.html.

[9] Long Pan (formerly known as Lao Huxia) hydropower dam in Dechen Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan plans to relocate about 10,000 residents. Similarly Yangqu hydropower dam in Qinghai will relocate 9,238 residents. See 青海新聞網 (Qinghai News Network). (8 April 2019). 库区移民冲刺全面小康——青海大中型水利水电工程搬迁群众生活状况调查’ (Immigrants in the reservoir area strive to achieve a comprehensive well-off society—A survey on the living conditions of people relocated to large and medium-sized water conservancy and hydropower projects in Qinghai). https://kknews.cc/other/8pbjr9e.html.

[10] Accounting for Yebatan, Lawa, Suwalong, Xulong (Rimian), and Longpan Hydropower dams.

[11] 重庆市发展和改革委员会 (Chonqing Municipal Development and Reform Commission). (黄河上游规划建设水电站23座 水库移民将达12万左右 (23 hydropower stations are planned to be built in the upper reaches of the Yellow River, and about 120,000 people will be immigrated to reservoirs). https://fzggw.cq.gov.cn/zwxx/bmdt/202002/t20200212_5175017_wap.html.

[12] 新华网 (Xinhua net). (20 November 2020). 西藏未来三年向11省市送电61亿千瓦时’ (Tibet will send 6.1 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity to 11 provinces and cities in the next three years). http://m.xinhuanet.com/2020-11/20/c_1126766162.htm.

[13] Yeh, Emily T. Written submission, Congressional-Executive Commission on China: Hearing on China’s Environmental Challenges and U.S. Responses September 21, 2021.

[14] Guardian. (10 April 2004). Chinese premier reprieves Grand Canyon of the Orient. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2004/apr/10/china.jonathanwatts, and Michael Standaert for Earth Journalism Network. (21 October 2020). With activists silenced, China moves ahead on big dam project. https://earthjournalism.net/stories/with-activists-silenced-china-moves-ahead-on-big-dam-project.

[15] Guardian. (1 February 2011). China’s big hydro wins permission for 21.3 GW dam in world heritage site., https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2011/feb/01/renewableenergy-china.

[16] High Peaks Pure Earth. (4 March 2024). The History of Wontoe Monastery in the Encyclopedia of Monasteries and Temples in Kham. https://highpeakspureearth.com/the-history-of-wontoe-monastery-in-the-encyclopedia-of-monasteries-and-temples-in-kham/.

[17] High Peaks Pure Earth. (2024, April 16). The sacred murals of Wontoe Monastery in Dege. https://highpeakspureearth.com/the-sacred-murals-of-wontoe-monastery-in-dege/.

[18] Footage dated 21 February 2024 available on Radio Free Asia. See Radio Free Asia (27 February 2024). Chinese authorities release dozens of Tibetans arrested for dam protests. Translation from a presentation by Dawa Lokyitsang on 12 April 2024 at University of Colorado Boulder.

[19] Invisible Tibet. (29 October 2012). Tibetans’ opposition to the call to build hydropower stations, and “Water from Paomaquan to Tibet—On the Great Development of Hydropower in Tibet., woeser.middle-way.net/2012/10/blog-post_29.html.

[20] Due to Chinese-language websites regularly expiring, we cannot currently retrieve the website details. However, information was formerly available at: http://www.Derge.gov.cn/gzdgx/c101479/202204/c9b4c3fcf4244eb7bfd1d32dbd6f8104.shtml.

[21] 江达党建 (Jiangda party building). (25 February 2024). 入娘西乡、卡贡乡、岗托镇、汪布顶乡、岩比乡、波罗乡调研指导工作’ (Baima Zhaxi went to Niangxi Township, Kagong Township, Gangtuo Town, Wangbuting Township, Yanbi Township, and Boluo Township for research and guidance). https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/aT3BHJRJK4SvgM2HjmJeSw?poc_token=HNfq6WWjPmAyqBuyCssHeo7ODUXQLMQAio6vS7-C.

[22] 德格县融媒体中心 (Derge County integrated Media Center). (28 April 2022). 做好前期准备工作 不断加快推动德格清洁能源开发 助力乡村振兴’ (Make preliminary preparation and continue to accelerate the development of clean energy in Derge to help rural revitalization). https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzIwMDE0ODAzMQ==&mid=2649313669&idx=3&sn=cf953cd3fdf34224ad0ded0056e726ec&chksm=8e9c64d5b9ebedc31cad00d66058e2256eb20acc72d9a4321ae4d4c5e4117d8df896da6a13b4&scene=27.

[23] Wenbiao Sha. 3 October 2022. ‘The political impacts of land expropriation in China, Journal of Development Economics. Vol. 160. January 2023. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0304387822001274.

[24] Legeng Liu. (26 August 2015). Saving Tiger Leaping Gorge: A Reflection. https://archive.internationalrivers.org/blogs/433-1.

[25] Guardian. (4 March 2011). China’s dam-building will cause more problems than it solves. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2011/mar/04/china-dams-emissions-carbon-hydropower.