Summary of findings

The general international understanding of Indian connection to Tibet is limited to the political aspect, which does not give the complete picture of the situation. This report highlights the multifaceted nature of Indian connection to Tibetan affairs.

There is an ongoing India-China competition on the international stage on these aspects, showing how they are intrinsically linked with India’s core interest.

Following Chinese Communist occupation of Tibet, Indian governmental agencies have been adopting somewhat contradictory policies on Tibet, with the political establishment showing much deference to “sensitivities” projected by China and the military-security establishment on the other hand being more aggressive, concerned with Chinese takeover of Tibet and the subsequent developments.

Tibet’s Buddhist heritage is the most visible indicator of its historical connection with India. It is followed by people across the Himalayan region of northern India, from Arunachal Pradesh in the east to Sikkim, Kalimpong, Darjeeling, Himachal Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Ladakh to the northwest. Their strategic value and stake in the future of Tibetan Buddhism is something that Indian policymakers have only lately acknowledged. Today, we are seeing a concerted and visible effort not only at highlighting India’s Buddhist heritage, but also its desire to play the leading role in its future direction.

The traditional Indian healing system known as Ayurveda is one of the three main systems (Indian, Chinese and Unani traditions) that have enriched the Tibetan medical system (formally known as Sowa Rigpa or Science of Healing). More importantly to the issue of this report, this science of healing has been practiced all along the Indian Himalayas (Ladakh, Lahaul & Spiti, Arunachal Pradesh, Sikkim, Darjeeling, Kalimpong, etc) for centuries. It was only in September 2010 that India bestowed official recognition to Sowa Rigpa system. This recognition has the potential to provide much-needed legitimacy to the healing system both in India and internationally if the Indian authorities can take the necessary steps.

Another area in which India has taken initiative, but neglected projecting it appropriately, is the field of Tibetan studies. The very many Tibetan institutes can play a role in appropriately highlighting the Indian stake on matters relating to Tibet and Tibetans.

Tibetan rivers have been the fountain head for the growth of civilization in south and south east Asia with an estimated 1.8 billion people dependent on their healthy, unimpeded flow. China’s usage of Tibetan waters—particularly hydroelectric dams, both existent and planned, is having a devastating impact on downstream countries, including India. The associated risks will only worsen as the climate crisis increases and water scarcity stands to dramatically grow. However, this Indian stake in the Tibetan waters has yet to be adequately addressed by Indian policy makers when talking about their government’s approach towards Tibet and Tibetans.

Prior to the Chinese Communist occupation of Tibet in 1959, Tibet had served as a buffer between the two Asian giants, India and China, contributing to regional stability. However, after 1959, the historical Indo-Tibetan border has become a bone of contention between India and China. The Indian misplaced assumption of Chinese agreement on the border subsequently led to India’s defeat in a war between the two in 1962 and several skirmishes thereafter. India does not make adequate effort to connect the border resolution to the broader Tibetan issue.

One area where India will face challenge in the coming decades is the future of the institution of the Dalai Lama. India has not formally announced its stake in the issue, but the reality is that the issue of the future Dalai Lama is one that will have implications on the critical mass of Indian citizens in the Himalayan region who revere him as their spiritual leader. The people along India’s Himalayan region have not been constrained about their interest in the future of the Dalai Lama. There has also been a public debate in India for some time on the need to be more assertive on the issue of the Dalai Lama.

The situation calls for a holistic approach by the Indian government to its Tibet policy beyond political confines as Indian policymakers are aware of these layers of the Indo-Tibetan issue. As outlined in this report, India continues to undertake several initiatives on matters relating to Tibetans, but politically it has hesitated in asserting itself, being wary of Chinese reaction.

India on the international stage

In 2023 India has been in the international spotlight as president of the G20, culminating in the G20 Leaders’ Summit from Sept. 9-10, 2023 bringing the leaders of the world to New Delhi. This high-profile position, as well as recent international developments, has initiated public debate within the country on India’s place in the world. Unlike China, India has been cautious in projecting itself as a leading nation in the world, but it is taking incremental steps in being approached on its own merit. Like many countries in the region and the world, India, too, is currently debating on the best approach to challenge an aggressive China. Observers in India, including policymakers, have been suggesting that one way to do it would be to review India’s policy on Tibet and to adopt a more pragmatic and realistic one.

Following the escape of the Dalai Lama and thousands of Tibetans to India in 1959 and thereafter, following the Chinese Communist occupation of Tibet, Indian governmental agencies have been adopting somewhat contradictory policies on Tibet. The political establishment has been showing deference to “sensitivities” projected by China so much so that Indian analysts have charged successive Indian administrations with trying to appease China.[1] For example, on the issue of contact between representatives of the Tibetan leadership in exile, including envoys of the Dalai Lama, and the Chinese Government, the outcome of which will have an impact on India, it has not publicly taken a position, unlike some others such as the United States and the European Union, who have been categorical in their support.

The military-security establishment on the other hand has shown itself to be more aggressive, concerned with the Chinese takeover of Tibet and the subsequent developments. Soon after Tibet’s occupation by China, India’s Intelligence Bureau (IB) worked with the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to confront China and set up the paramilitary Special Frontier Force in 1962 composed of Tibetan refugees.[2]

The funeral in Ladakh of a Tibetan, Nyima Tenzin, who was a member of the secretive Special Frontier Force of India, on Sept. 8, 2020. He was killed in a landmine blast in an operation along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) during Aug. 29-30, 2020.

The general international understanding of Indian connection to Tibet is limited to the above political aspect, but it does not give the complete picture of the situation. This report highlights the multifaceted nature of Indian connection to Tibetan affairs and how India is trying to play a more assertive role to embrace it positively. It also focuses on the India-China competition on the international stage on these aspects, showing how these are intrinsically linked with India’s core interest. This report aims to broaden the public debate on India’s relations with Tibet, which currently seems restricted merely to the narrow political aspect, neglecting the broader foundational issues that merit a new approach on Indian policy.

China has launched a campaign to completely Sinify all aspects of Tibetan lives and to establish its claim to Tibet internationally, too. India is making efforts to meet the Chinese challenges and taking cautious steps. The situation calls for a holistic approach by the Indian government to its Tibet policy beyond political confines. It is not that Indian policymakers are not aware of these layers of the Indo-Tibetan issue. As outlined in this report, India continues to undertake several initiatives on matters relating to Tibetans, but politically it has hesitated in asserting itself, being wary of Chinese reaction. In fact, the Dalai Lama had at times termed the Indian position on Tibet as being “overcautious” in deference to China.[3] India has not adopted a holistic policy on Tibet, and there is an absence of coordination among the different agencies that are involved with the Tibetan issue. This report concludes with a recommendation for the formalization of an all-encompassing Indian policy.

Buddhism as the new frontier in India-China competition

The Buddhist heritage of Tibet is a testament to its historical connection with India. The spread of Buddhism from India to Tibet and subsequent transformation of Tibetan society are somewhat well-known, but less apparent to the international community is the prevalence of Tibetan Buddhism across the Himalayan region of India, from Arunachal Pradesh in the east to Sikkim, Kalimpong, Darjeeling, Himachal Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Ladakh to the northwest. Indian policymakers have only recently come to terms with the strategic importance of Tibetan Buddhism and their stake in its future.

In the post-1959 period, after the Dalai Lama sought sanctuary in India, Tibetan Buddhism in the Himalayan region began to see a resurgence. The Dalai Lama can be seen as the main driving force behind this resurgence through his regular visits to these areas and his initiatives leading to the establishment of institutions for the study and promotion of Buddhism. The fact that the Dalai Lama continued the tradition of appointing the abbot of the Tawang Monastery in Arunachal Pradesh, which China has continued to claim, is noteworthy. While historically it was India, which the Dalai Lama calls the Guru (Indian term for teacher), that provided the Buddhist spiritual heritage to Tibet, called the Chela (disciple), in the post-1959 period, it is the Chela that is contributing to the reemergence of Buddhism as a force to reckon with in India.

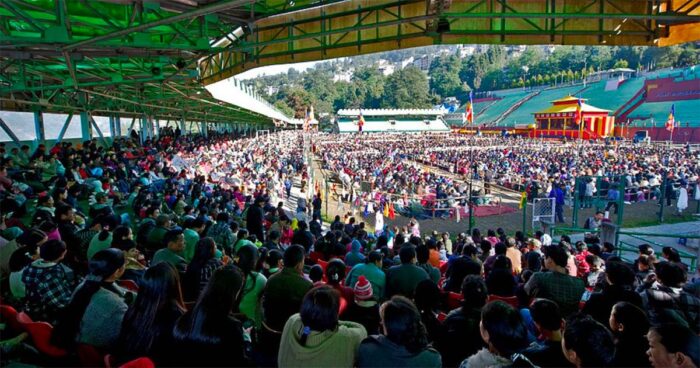

Devotees in Gangtok, Sikkim (which borders Tibet) gathered in the stadium there for a teaching by the Dalai Lama there on December 21, 2010. (Photo: Tenzin Choejor/OHHDL)

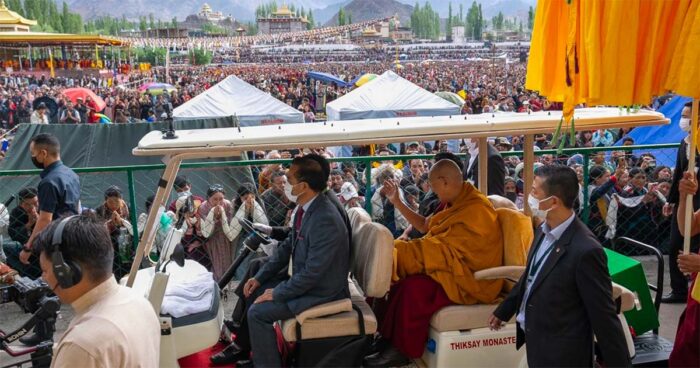

With devotees at the background, the Dalai Lama arriving at the teaching pavilion in Leh, Ladakh (which borders Tibet) on July 21, 2023. (Photo: Tenzin Choejor/OHHDL)

Some of the more than 50,000 devotees from Arunachal Pradesh (which borders Tibet) attending the Dalai Lama’s teaching in Tawang, on April 8, 2017. (Photo: Tenzin Choejor/OHHDL)

After a period of low-profile attempts to seize the opportunity provided by Buddhism (India played a behind-the-scenes role in the establishment and activities of an international NGO based in Mongolia, the Asian Buddhist Conference for Peace, in 1970[4]) and being somewhat of a silent spectator publicly in this development in the initial period, in recent decades, India has not only embraced the increasing interest in Buddhism but has also been visibly looking at this as an integral part of its international soft-power diplomacy. In general Tibetan Buddhism may be one of the most visible forms of Buddhism internationally, for the most part due to the Dalai Lama’s engagement. From a geostrategic perspective, there are traditional followers of Tibetan Buddhism outside of India, not only in the Indian subcontinent, but also in countries like Mongolia and the Russian Federation. India at least understood the implication of this to its relations with Mongolia and so strategically posted a Ladakhi, Sonam Norboo (who was a Tibetan Buddhist), as its first ambassador there in 1971.[5] Subsequently, a prominent Tibetan Buddhist master from Ladakh, known popularly as Kushok Bakula, became its ambassador there, serving there for an abnormally long time (from 1989 to 2000).[6] Bakula Rinpoche, as he is also known, is rightly credited for “strengthening the bilateral relation between the two countries by reviving and restructuring Buddhism in Mongolia.”[7] His tenure in Mongolia can be seen as one of the major soft-power diplomatic successes by India. Bakula was followed as Indian Ambassador to Mongolia by Karma Topden from Sikkim,[8] also a Tibetan Buddhist. These postings were kept low profile.

Today, we are seeing not only a concerted and visible effort at highlighting India’s Buddhist heritage, but also its desire to play the leading role in its future direction.

In November 2011, India hosted a Global Buddhist Congregation (GBC) attended by over 800 delegates and observers from Buddhist organizations and institutions from around the world. This meeting resulted in the establishment of the International Buddhist Confederation (IBC) in 2012. In both these initiatives, one could see that Buddhist leaders from the Indian Himalayan region were playing leading roles.

In April 2023, IBC organized the first Global Buddhist Summit, which was participated in by “171 delegates from foreign countries and 150 delegates from Indian Buddhist organizations,” according to India’s Ministry of Culture. Among those addressing it were the Dalai Lama, while the Indian prime minister made a visible presence, indicating the official stake in the summit.

The leadership of the re-established Tibetan Buddhist monastic institutes in India, initially held by Tibetan refugees, now are increasingly being shouldered by those from the Indian Himalayan region.

These developments have implications on the future of Tibetan Buddhism, particularly in the eventual post-Dalai Lama period. China has made its political agenda clear on this: Tibetan Buddhism is claimed as being part of “Chinese Buddhism” with no less than Xi Jinping being quoted by the Chinese state media as saying, “Tibetan Buddhism should be guided in adapting to the socialist society and should be developed in the Chinese context.”[9]

Tibetan medicine as the bone of contention

The medical field is another area where India has been late in its acknowledgement of Tibet’s significance. The traditional Indian healing system known as Ayurveda is one of the three main systems (Indian, Chinese and Unani traditions) that have enriched the Tibetan medical system (formally known as Sowa Rigpa or Science of Healing). More importantly to the issue of this report, this science of healing has been practiced all along the Indian Himalayas (Ladakh, Lahaul & Spiti, Arunachal Pradesh, Sikkim, Darjeeling, Kalimpong, etc) for centuries.[10]

Understanding its potential to contribute to the world, the Dalai Lama established the Tibetan Medical & Astro Institute in Dharamsala in 1961.[11] Beginning with just one physician and an astrologer, the TMAI, or Men-Tsee-Khang as it is known in Tibetan, today has become a well-respected institute of Sowa Rigpa learning throughout the world, attracting students from the Himalayan region and abroad, too.

However, like in the case of Tibetan Buddhism, the Indian authorities were slow to acknowledge its significance in India’s policy considerations. In the meantime, the Chinese have made headway in its international claims over Tibetan medicine. The Chinese government had been including the Tibetan medical system as part of its “Traditional Chinese Medicine”[12] and successfully inscribed “Lum medicinal bathing of Sowa Rigpa” as part of its intangible cultural heritage with UNESCO in 2018.[13]

Indian Minister for Traditional Medicine Sarbananda Sonowal laid the foundation stone for the new complex of the first-ever National Institute of Sowa Rigpa in Ladakh on Sept. 8, 2022.

Indian officials on the other hand seem to have been viewing the system as a form of “tribal medicine” until recently due to the fact that people of Ladakh and the Monpas of Arunachal Pradesh, etc. who are traditional practitioners of the Sowa Rigpa system are categorized under “scheduled tribes”[14] entitled for additional privileges under the Indian Constitution. It was only in September 2010 that India bestowed official recognition to Sowa Rigpa system.[15] This recognition has the potential to provide much-needed legitimacy to the healing system both in India and internationally if the Indian authorities can take the necessary steps. In 2017 India did file an application with UNESCO to inscribe Sowa Rigpa as part of its intangible Cultural Heritage, but the initiative does not seem to have moved forward.

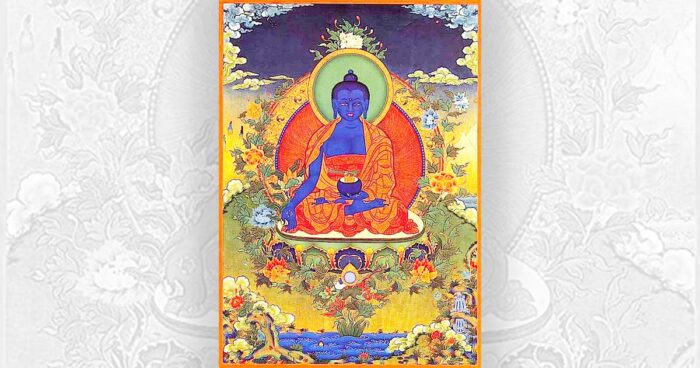

Thangka drawing of the Buddha of Medicine (known as Sangye Menla in Tibetan).

Nevertheless, in terms of grassroots practice of Sowa Rigpa, India has one critical advantage over China, namely incorporating a crucial spiritual element. Following the spread of Buddhism to Tibet, it also greatly influenced the traditional Tibetan medicine system, as can be seen from the Gyu Shi, the four tantras, which are the principal Tibetan medical texts.[16] There is even a Buddha of Medicine (known as Sangye Menla in Tibetan) whose rituals are an integral part of the study and practice of all aspects of Tibetan medicine.[17] In terms of pharmacology, particularly when it comes to “precious pills,” Buddhist prayers and rituals are an essential part of the preparation.[18] It is well-known that despite the physical infrastructure available in Tibet, the medical practitioners there do not have the requisite facilities and space to incorporate the necessary spiritual elements in their practice. Whereas in India, the practitioners of Sowa Rigpa have all the resources and ability to incorporate the needed ritual elements for making the study complete and the medicines efficacious. It is for this reason that Tibetans in Tibet greatly value the Tibetan medicines, particularly precious pills, produced by the Tibetan Medical & Astro Institute in Dharamsala in India even though factories in Tibet also produce such pills. Thus, India has the opportunity to be better in substance when it comes to Sowa Rigpa.

India as center of Tibetan studies

Another area in which India has taken initiative, but neglected projecting it appropriately, is the field of Tibetan studies. In hindsight, it began way back in 1958 when, through support of India and the Dalai Lama, then-Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, when the then-Choegyal of independent Sikkim Palden Thondup Namgyal, established The Namgyal Institute of Tibetology.[19] In addition to its initial purpose “to preserve the invaluable texts on history, religion, literature and science brought from Tibet at the time of the region’s political turmoil in the 1950’s” the institute promotes research on Mahayana Buddhism, religious art, language and culture of Sikkim and other Himalayan regions.[20]

Similarly, after the flight of the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan refugees in 1959, India supported the establishment of several key institutes for Tibetan studies.

In the 1960s, the Central Institute of Buddhist Studies was established in Ladakh to provide an alternative for the monastic community there to pursue their Tibetan Buddhist studies in the wake of the Chinese occupation of Tibet.[21]

The Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts (TIPA), a premier institute for preserving and promoting Tibetan musical heritage and arts, was established in 1959.[22] Initially known as Tibetan Music, Dance, and Drama Society, TIPA has established a credible name for itself internationally. Interestingly, TIPA has not only inspired the setting up of The Monpa Institute of Performing Arts by the government of Arunachal Pradesh to preserve and promote the culture and tradition of its Monpa community, but also conducted training for its artists.[23]

Artists from the Monpa Institute of Performing Arts of Arunachal Pradesh with artists from the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts after finishing a course at the institute in August 2021.

The Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies was established in 1967 at Sarnath, Varanasi, following “a dialogue between Pt. Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of India and His Holiness the Dalai Lama with a view to educating the young Tibetan Diaspora and those from the Himalayan border regions of India, who have religion, culture and language in common with Tibet.”[24] Since then it has become a well-established and respected center for Tibetan religion and culture with students from all over the Himalayan region and abroad.

Equally well known is the Library of Tibetan Works & Archives in Dharamsala, which was founded in 1970 by the Dalai Lama “to restore, protect, preserve and promote the culture.”[25] The LTWA was a magnet for students of Tibetology from all over the world and many of the prominent Tibetologists throughout the world have benefited from its resources and programs.

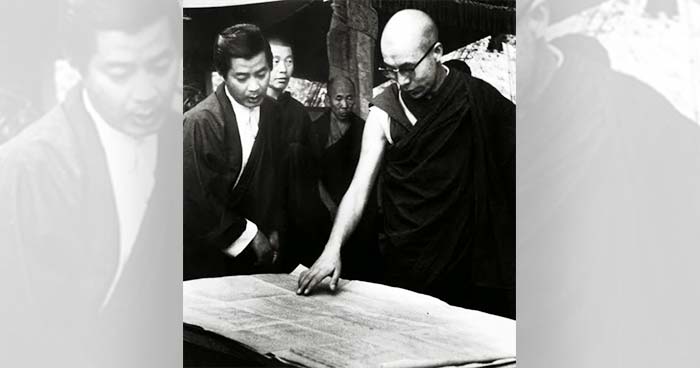

An undated photo of the Dalai Lama studying the blueprint of the new construction for the Library of Tibetan Works & Archives with its Director Gyatsho Tshering standing beside him. (Photo: LTWA)

Tibetan waters as India’s source of life

China’s usage of Tibetan waters is having a severe impact on downstream countries, with India bearing the brunt. Of particular concern are extant and planned hydroelectric dams and massive water diversion projects.

Tibetan rivers have been the fountainhead for the growth of civilization in South and Southeast Asia with an estimated 1.8 billion people dependent on their healthy, unimpeded flow. Among them is the mighty Yarlung Tsangpo (Brahmaputra), which has a direct implication on India. A 2021 report supported by core funds of the Nepal-based research institute ICIMOD outlines the impact of this river on South Asia:

The Brahmaputra river system, including its tributaries, provides a lifeline for millions of people. On the one hand, it has sustained a plethora of ecosystems, human societies, and cultures in South Asia for thousands of years, contributing to the survival and flourishing of national economies of four basin countries. On the other hand, the river generates catastrophic floods leading to the loss of riparian landmass every year, affecting the lives and livelihoods of millions of people, and the region’s economy, infrastructure, and environment.[26]

Yet, interventions into river systems need to be cognizant of principles of sustainability, being considerate of negative impacts of human intervention.

Rivers in Tibet: images courtesy of Michael Buckley, author of Meltdown in Tibet.

According to the Central Tibetan Administration in Dharamsala, “melting glaciers of Tibetan Plateau provide a key source of water in the summer months providing 70 percent of the summer flow in the Ganges and 50-60 percent of the flow in other major rivers.”[27] A report by the Washington, DC-based think tank The Atlantic Council in 2019 said this about India-China relations and the water issue: “Decades-old mutual suspicion hangs over the relationships among all these powers, with transboundary rivers forming an important component of this mistrust.”[28]

Multiple dams are being built on all the major rivers running off the Tibetan Plateau by powerful state-owned Chinese consortiums.[29] There are plans for a mammoth water-diversion scheme across some of the restive areas of Tibet to transfer water to parched northern China, despite the high risk and concern downstream as the plateau is one of the Earth’s most seismically active regions.[30] The associated risks of these projects will only worsen as the climate crisis increases and water scarcity dramatically grows.

However, this Indian stake in the Tibetan waters has yet to be adequately addressed by Indian policy makers when talking about their government’s approach towards Tibet and Tibetans.

However, this Indian stake in Tibetan waters is not much looked at by Indian policymakers when talking about their government’s approach toward Tibet and Tibetans.

The Atlantic Council report says that remedial action can be taken. It says, “Himalayan Asia’s transboundary water dynamics threaten to erode interstate cooperation, including among the continent’s major powers, risk worsening geopolitical competition, and heighten the odds of domestic and interstate conflict. Yet there are viable pathways for avoiding such outcomes, the most important of which treat water as a shared resource to be managed cooperatively.”[31]

Asok Kumar, the director general of the Indian Ministry of Water Power, speaking at the “Addressing Water Security Challenges in the Himalayan Region” at the World Water Week Conference in Stockholm, Sweden, on Aug. 24, 2023. (Screenshot)

India is becoming assertive, and this needs to continue. Asok Kumar, an official of the Indian Ministry of Water Power, whose mandate includes “(M)atters relating to rivers common to India and neighboring countries,” while taking part in an international event on “Addressing Water Security Challenges in the Himalayan Region” at the World Water Week Conference in Stockholm in August 2023[32] pointed to the significance of the Tibetan water supply to downstream countries, saying, “Hence we are also very much concerned about the environmental set up in the Himalayan regions.” The US State Department convened the event in partnership with the International Water Management Institute. US Under Secretary of State Uzra Zeya (who is also the Special Coordinator for Tibetan Issues), sent a recorded message emphasizing the increased large-scale water diversion projects and hydropower development across the Tibetan Plateau in recent years. She added, “These policies have been designed and implemented without input from the 6 million Tibetans in China, leading to the displacement of traditional Tibetan communities,” and “These projects have also had negative implications for the water security of downstream nations.”

Unresolved India-China talks over the Indo-Tibetan border

Prior to the Chinese Communist occupation of Tibet, the country had served as a buffer between the two Asian giants, India and China, contributing to regional stability.[33] However, since 1959, the historical Indo-Tibetan border has become a bone of contention between India and China. The dispute on the contested border led to war between the two countries in 1962 and several skirmishes thereafter.

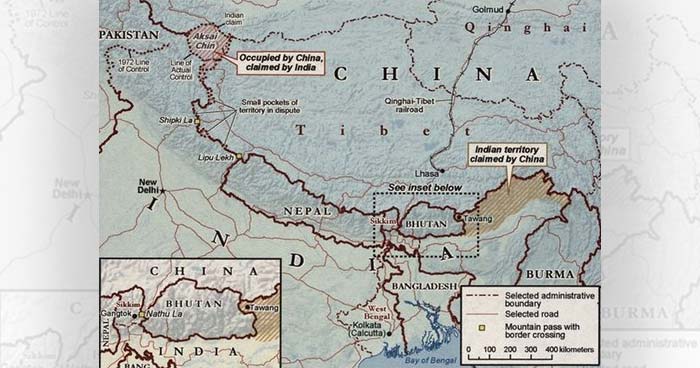

After India had to face a disastrous defeat in the 1962 war with China, both countries had an understanding of respecting what is called the “Line of Actual Control” (LAC) that reflects the reality of control by each of them until a solution is reached. The LAC is divided into three sectors: the eastern sector, which spans Arunachal Pradesh and Sikkim, the middle section in Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh, and the western sector in Ladakh. Both sides have claims on territory of the other country that goes beyond the LAC. Despite several rounds of talks, they have not been able to see progress on the issue. The most problematic sector is the eastern sector, where India maintains that the McMahon Line is the border. China says it does not recognize this border demarcation.

The Line of Actual Control between China and India. (Map: US Central Intelligence Agency)

Before going into details, at the broader level, on the issue of the border, there are a few relevant points of consideration. The first is the 1914 Simla Convention, at which the McMahon Line was decided. The second is the 1954 Agreement on Trade and Intercourse Between Tibet Region of China and India,[34] the first agreement on Tibet that independent India reached with the Communist Chinese in which Tibet is referred to as a ”region of China.” The third is the 2003 India-China Joint Declaration signed on June 23, 2003, which for the first time said, “The Indian side recognizes that the Tibet Autonomous Region is part of the territory of the People’s Republic of China.”[35]

The McMahon Line is the name given to the boundary between Tibet and then-British India (which also included Burma) as agreed at the 1914 Simla Convention. In the 1954 agreement, India not only referred to Tibet as a region of China, but also gave up the rights and privileges it enjoyed in Tibet, inherited from British India. This seems to have been done because India wrongly assumed that the Chinese side did not have any problems with the issue of the border, including the McMahon Line. In fact, when the Chinese side raised their reservations over the border in subsequent years, the then-Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in a letter in December 1958 to then-Chinese Prime Minister Zhou En-Lai specifically referred to this, saying that in 1954, “No border questions were raised at that time and we were under the impression that there were no border disputes between our respective countries. In fact we thought that the Sino-Indian Agreement, which was happily concluded in 1954, had settled all outstanding problems between our two countries.”[36]

India subsequently suffered a humiliating defeat on account of this misplaced assumption when Chinese forces launched a war against it in 1962.[37]

Chinese Premier Zhao’s response to Nehru, in a letter in January 1959,[38] also raised another critical matter regarding the McMahon Line. Zhao said the line “was a product of the British policy of aggression against the Tibet region of China” and that, “Juridically, too, it cannot be considered legal.”

This draws attention to a seeming contradiction posed by the Indian position on the border and its approach toward Tibet. As early as September 1959, the Dalai Lama drew attention to this in his remarks to the Indian Council on World Affairs in New Delhi on the “The International Status of Tibet,” and given its significance, it merits repeating here. He said,

I should like to invite your attention, ladies and gentlemen, to an extremely important question which arises in this connection. The Government of India contends that the boundary between Tibet and India was finally settled according to the McMahon Line, but this frontier was laid down by the Simla Convention and this Convention was only valid and binding as between Tibet and the British Government. If Tibet did not enjoy international status at the time of the conclusion of the Convention, she had no authority to enter into such an agreement. Therefore, it is abundantly clear that if you deny sovereign status to Tibet, you deny the validity of the Simla Convention and, therefore, you deny the validity of the McMahon Line. On the other hand, if the McMahon Line is valid and binding, the Simla Convention must be valid and binding. And, therefore, it follows as a logical corollary that Tibet did possess sovereign and international status at the time when she concluded the Simla Convention. And if she did possess sovereign status in 1914, nothing happened subsequently to impair that status in any manner.[39]

Indian policymakers may have noted this, although there is no visible indication of finding a way to address this discrepancy.

Interestingly, however, way back in 1962, the United States had already taken a decision to “recognize the McMahon line as the traditional border between India and China (this is the Northeast border).”[40]

Promulgation of Tibetan Rehabilitation Policy

In 2014, after 55 years of resettling Tibetan refugees, the Indian government formally announced the “Tibetan Rehabilitation Policy, 2014” that was done “to provide a uniform Guideline clearly demarcating the facilities to be extended to the Tibetan Refugees living within the jurisdiction of each State Government.”[41] Prior to this, there was no clarity on the socioeconomic facilities to the Tibetan refugees, who were resettled in 10 Indian states. The Tibetan leadership in Dharamsala welcomed this, saying, “This guideline has made a clear policy statement about the welfare of the Tibetans in India.”[42]

However, although a major initiative by India, this guideline does not cover the entire gamut of Indian approaches to matters relating to Tibet and Tibetans, as it is limited to addressing socioeconomic needs of the Tibetan refugees.

Indian stake in future of the Dalai Lama institution

One area where India will face challenge in the coming decades is the future of the institution of the Dalai Lama. India has not formally announced its stake in the issue, but the reality is that the issue of the future Dalai Lama is one that will have implications on the critical mass of Indian citizens in the Himalayan region who revere him as their spiritual leader. China has already been publicly asserting its authority by claiming to have the right to decide on all matters concerning the Dalai Lama, including on his reincarnation. Indian formal position, on the other hand, is a cautious one, appearing to look at the Dalai Lama and his institution as merely Tibetan and having come into their sphere of concern only after 1959. In 2018, in response to a query regarding a recent media report on the government’s position on His Holiness the Dalai Lama, the official spokesperson said: “Government of India’s position on His Holiness the Dalai Lama is clear and consistent. He is a revered religious leader and is deeply respected by the people of India. There is no change in that position. His Holiness is accorded all freedom to carry out his religious activities in India.”[43]

The present 14th Dalai Lama has on his part given enough indication on how the future of the institution should be. In 2011, he came out with a formal statement that addressed the entire gamut of his reincarnation.[44] In it, he said, “The main purpose of the appearance of a reincarnation is to continue the predecessor’s unfinished work to serve Dharma and beings” and only he had the authority to decide on the 15th Dalai Lama. In 2004, he even said, “My life is outside Tibet, therefore my reincarnation will logically be found outside”[45] so that the reincarnation can continue the mission.

The people along India’s Himalayan region have not been reticent about their interest in the future of the Dalai Lama. His visits to places like Ladakh, Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh, etc., are emotionally moving experiences to the thousands of Buddhists that reside there. Understanding the bond between them and the Dalai Lama, politicians in the region leave no stone unturned to arrange for his visit and to be visibly part of the engagements. It is also an open secret that monastic and community leaders hope that a future Dalai Lama will take birth in their region. In 2017, when he was visiting the border town of Tawang in Arunachal Pradesh, the following was his response to the media (posted on the official website of the Office of the Dalai Lama) who had asked about his reincarnation: “When it was suggested that the people of Tawang would dearly love to have a Dalai Lama born amongst them again, His Holiness responded that there are people who say the same thing in Ladakh and even in Europe too.”[46] In August 2023, the Dalai Lama paid a very successful visit to Ladakh, where he expressed his gratitude for the people’s very strong devotion to him. Buddhists in Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh (both states located along the Indo-Tibetan border) have also supplicated to the Dalai Lama to visit their states.

The Dalai Lama talking to the media in Tawang in Arunachal Pradesh on April 8, 2017, during which he talked about where his reincarnation might come from. (Photo: Tenzin Choejor/OHHDL)

There has also been a public debate in India for some time on the need to be more assertive on the issue of the Dalai Lama. In 2019, 200 Members of the Indian Parliament asked their government to award the Dalai Lama with India’s highest civilian award, the Bharat Ratna. Indrani Bagchi, a foreign policy commentator and CEO of the Ananta Aspen Centre (which promotes dialogue among policymakers in India), had said India has “important reasons to facilitate and guide Dalai Lama’s reincarnation” (italics ours).[47]

As discussed earlier, India has not been categorical on how it feels on the issue of the Dalai Lama’s reincarnation. On the other hand, the United States, in response to Tibetan Americans and Tibet supporters and considering the geostrategic implications of the Dalai Lama’s reincarnation, has legislated its position that the Dalai Lama’s succession is a strictly religious issue that only he and his followers can decide on. If Chinese officials attempt to name a future Dalai Lama, they will face sanctions that could include having their assets frozen and their entry to the US denied.[48]

Recommendations

- India needs to acknowledge being a stakeholder on issues of Tibet and Tibetans. While Indian officials do closely monitor developments in Tibet, publicly there is the appearance that these developments are of minimal concern for India.

- India should formalize a coordinated policy on Tibet and Tibetans. This would mean coordination between various Indian agencies, including from the Ministry of External Affairs to Ministry of Defense, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Ministry of Culture and Ministry of Water Power, as well as the governments in the states along the Himalayan region that share their borders with Tibet as well as those who host a sizable Tibetan settlement.

- India should formally express its position on the Dalai Lama institution and consider it not merely a Tibetan issue but one that has implications on followers of Tibetan Buddhism in India.

- India should publicly adopt a clear position on the issue of the reincarnation of the Dalai Lama.

- India should prioritize the impact of the waters from the Tibetan Plateau high in its national security strategy and formulate policies accordingly, including forcefully pressing for accountability based cooperative management and engage as a key participant in relevant UN bodies.

- Existing institutions in India like the Library of Tibetan Works & Archives, the Tibetan Medical & Astro. Institute and the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts (all based in Dharamsala) should be given recognition as national-level academies by the Indian government.

- India should further expand the legally mandated rights of Tibetan refugees to apply for Indian citizenship by loosening any extraneous considerations being made for the process.

- India should work with like-minded countries, particularly in Europe and the United States, to coordinate approaches on Tibet.

Footnotes:

[1] India’s appeasement policy towards China unravels, Brahma Chellaney, The Strategist, 10 Jun 2020, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/indias-appeasement-policy-towards-china-unravels/

[2] In the shadows of Bluestar, Kargil, LAC, India’s ‘secret’ Special Frontier Force turns 60, Pia Krishnankutty, The Print, November 14, 2022, https://theprint.in/india/in-the-shadows-of-bluestar-kargil-lac-indias-secret-special-frontier-force-turns-60/1215934/

[3] Dalai Lama describes India ‘over-cautious’ in dealing with China, Nov 23, 2008, https://zeenews.india.com/news/world/dalai-lama-describes-india-over-cautious-in-dealing-with-china_485840.html

[4] Asian Buddhist Conference For Peace (ABCP) https://abcp.mn/about-us/#:~:text=Asian%20Buddhist%20Conference%20for%20Peace%20(ABCP)%20was%20founded%20in%201970,(monks)%20and%20lay%20members.

[5] Embassy of India in Mongolia website, accessed on August 23, 2023, https://eoi.gov.in/ulaanbaatar/?1043?000

[7] “Kushok Bakula Rinpoche and his contribution to revival of Buddhism in Mongolia”, ANI, June 13, 2022, https://theprint.in/world/kushok-bakula-rinpoche-and-his-contribution-to-revival-of-buddhism-in-mongolia/995009/

[9] “Xi stresses building new modern socialist Tibet,” Xinhua, August 29, 2020, https://web.archive.org/web/20230822205615/http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-08/29/c_139327765.htm

[10] “Health traditions of Buddhist community and role of amchis in trans-Himalayan region of India” Chandra Prakash Kala, Current Science, Vol. 89, No. 8 (25 October 2005), pp. 1331-1338 (8 pages) https://www.jstor.org/stable/24110838

[11] Tibetan Medical & Astro Institute in Dharamsala, https://mentseekhang.org/tmai-in-exile/

[12] “Traditional Tibetan Medicine,” Embassy of the People’s Republic Of China in the Republic Of Latvia, May 9, 2006

[13] “China’s Tibetan medicinal bathing listed as Intangible Cultural Heritage,” Xinhua, November 29, 2018, https://web.archive.org/web/20230823173556/http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-11/29/c_137638079.htm

[14] Stephan Kloos, Laurent Pordié. Introduction: The Indian Face of Sowa Rigpa. Healing at the Periphery: Ethnographies of Tibetan Medicine in India, Duke University Press, In press. ffhal-03102907

[15] Bill passed in Rajya Sabha to recognise Sowa-Rigpa system of medicine, Times of India, August 26, 2010, http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/articleshow/6434971.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst

[16] History of Tibetan medicine, Tibetan Medical & Astro Institute, Dharamsala, https://mentseekhang.org/history-of-tibetan-medicine/

[17] “Importance of Medicine Buddha in the Traditional Tibetan Medical System”, Institute of Traditional Tibetan Medicin, Poland, https://tibetanmedicalinstitute.com/medicine-buddha/

[18] The Administration of Tibetan Precious Pills, Efficacy in Historical and Ritual Contexts, Olaf Czaja, Asian Med (Lieden). 2015; 10(1-2): 36–89, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5154374/

[19] Namgyal Institute of Tibetology, Gangtok, Sikkim, https://namgyalinstitutesikkim.org/

[21] Central Institute of Buddhist Studies was established in Ladakh https://cibs.ac.in/historical-background/

[22] Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts, Dharamsala, https://tipa.asia/about-us

[23] Crash Course Training Program for 9 MIPA Artistes, August 5, 2021, https://tipa.asia/blog/crash-course-training-program-for-9-mipa-artistes/

[24] Welcome to Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies, Sarnath, India, https://www.cihts.ac.in/webpage/index.aspx#

[25] History of LTWA, Dharamsala, https://tibetanlibrary.org/history-of-ltwa/

[26] Pradhan, N.S.; Das, P.J.; Gupta, N.; Shrestha, A.B. Sustainable Management Options for Healthy Rivers in South Asia: The Case of Brahmaputra. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1087. https://doi.org/10.3390/su1303108

[27] “Tibetan Plateau under the mercy of climate change and modernization,” Central Tibetan Administration, May 5, 2009, https://tibet.net/tibetan-plateau-under-the-mercy-of-climate-change-and-modernization/

[28] “Ecology meets Geopolitics: Water Security in Himalayan Asia,” Atlantic Council, April 2019, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/AC_ECOLOGY_032719B_FINAL_int-1.pdf

[29] “Damming Tibet’s rivers: new threats to Tibetan area under UNESCO protection,” International Campaign for Tibet, May 30, 2019, https://savetibet.org/damming-tibets-rivers-new-threats-to-tibetan-area-under-unesco-protection/

[30] “Divided waters in China, Chinese scientists troubled by radical proposals to divert Tibet’s water are making their voices heard. Zhou Wei listened in at a seminar about the Shuotian Canal,” Zhou Wei, China Dialogue, September 20, 2011, https://chinadialogue.net/en/nature/4539-divided-waters-in-china/

[31] “Ecology meets Geopolitics: Water Security in Himalayan Asia,” Atlantic Council, April 2019, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/AC_ECOLOGY_032719B_FINAL_int-1.pdf

[32] “State Department panel highlights water security in Tibet, Himalayas,” International Campaign for Tibet, August 29, 2023, https://savetibet.org/state-department-panel-highlights-water-security-in-tibet-himalayas/

[33] “Tibet’s value as an independent buffer state was integral to the region’s stability” His Holiness the Dalai Lama in his “Five Point Peace Plan” address to the US Congressional Human Rights Caucus, September 21, 1987, https://www.dalailama.com/messages/tibet/five-point-peace-plan

[34] Agreement between the Republic of India and the People’s Republic of China on Trade and Intercourse Between Tibet Region of China and India, Indian Ministry of External Affairs, April 29, 1954, https://www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/7807/Agreement+on+Trade+and+Intercourse+with+Tibet+Region

[35] India’s semantic diplomacy with China on Tibet, International Campaign for Tibet, June 24, 2003 https://savetibet.org/indias-semantic-diplomacy-with-china-on-tibet/

[36] Notes, Memoranda and letters Exchanged and Agreements signed between The Governments of India and China 1954 –1959, Page 55, White Paper I, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, https://www.claudearpi.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/WhitePaper1NEW.pdf

[37] “India-China War 50 years later” The Tribute, 2022, https://www.tribuneindia.com/2012/specials/china.htm

[38] Letter from Prime Minister of China to the Prime Minister of India, January 23, 1959 https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/letter-prime-minister-china-prime-minister-india-23-january-1959

[39] “The International Status of Tibet,” His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Indian Council of World Affairs, New Delhi, September 7, 1959 as reproduced in “One Hundred Thousand Moons, An Advanced Political History of Tibet” Tsepon Wangchuk Deden Shakabpa, Vol 2, 2010. Page 1051. There is a typo as the English translation lists the day of the speech as November 7, 1959 whereas it was on September 7, 1959

[40] Foreign relations of the United States, 1961–1963, Volume XIX, South Asia, Washington, October 26, 1962, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v19/d181

[41] “Tibetan Rehabilitation Policy, 2014”, Ministry of Home Affairs, New Delhi, https://www.mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/2022-08/FFR_ANNEXURE_A_17092019%5B1%5D.pdf

[42] “Government of India formalises Tibetan Rehabilitation Policy 2014,” Central Tibetan Administration, October 21, 2014, https://tibet.net/government-of-india-formalises-tibetan-rehabiliation-policy-2014/

[43] “Official Spokesperson’s response to a query regarding a recent media report on the Government’s position on His Holiness the Dalai Lama”, Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi, March 02, 2018, https://www.mea.gov.in/response-to-queries.htm?dtl/31316/official+spokespersons+response+to+a+query+regarding+a+recent+media+report+on+the+governments+position+on+his+holiness+the+dalai+lama

[44] Reincarnation, The Dalai Lama, Dharamsala, September 24, 2011 https://www.dalailama.com/the-dalai-lama/biography-and-daily-life/reincarnation

[45] “A Conversation with the Dalai Lama” Alex Perry, TIME, Oct. 18, 2004, https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,725176,00.html

[46] “His Holiness the Dalai Lama Gives Buddhist Teachings to 50,000 in Tawang” Office of H.H. the Dalai Lama, April 8, 2017, https://www.dalailama.com/news/2017/his-holiness-the-dalai-lama-gives-buddhist-teachings-to-50-000-in-tawang

[47] “India should declare support for Dalai Lama’s reincarnation as the spiritual leader directs it,” Indrani Bagchi, Times of India, July 12, 2021, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/globespotting/india-should-declare-support-for-dalai-lamas-reincarnation-as-the-spiritual-leader-directs-it/

[48] “Congress passes key legislation supporting Tibetans’ aspirations, rights”, International Campaign for Tibet, December 21, 2020, https://savetibet.org/congress-passes-key-legislation-supporting-tibetans-aspirations-rights/