- Troop presence has been stepped up in Nagchu and local schools closed following a failed attempt by the authorities to compel families and monasteries in the area to raise Chinese national flags to mark the founding anniversary of the People’s Republic of China on October 1.

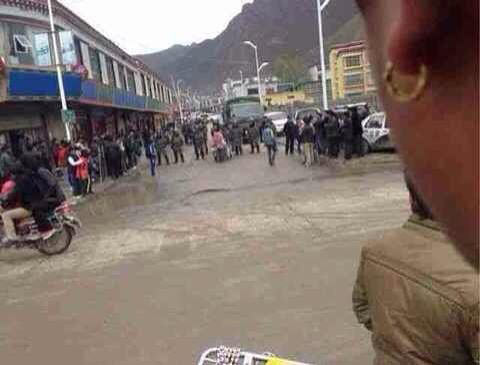

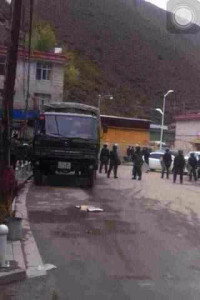

- New images show troops enforcing a lockdown in Driru (Chinese: Biru) county after people in two villages displayed prayer flags and refused to raise the Chinese flag for China’s National Day. According to Tibetan sources, local schoolchildren in the area did not attend performances for the celebration of National Day. Some schools in the area have now been closed, and Radio Free Asia reports that Mowa township, where Tibetans had refused to display the flag, has been turned into “a military camp”.

- Attempts by the Chinese authorities to force Tibetans to display the Chinese flag on their homes and in monasteries have been met with determined resistance and have led to deepening tensions in various parts of the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR).

More photos below.

The resistance in Nagchu (Chinese: Naqu) occurred just days after Tibet Autonomous Region Party Secretary Chen Quanguo visited Chamdo in the TAR (Chinese: Changdu or Qamdo) from September 25 to 27. Chen expressed his appreciation to local officials for maintaining a consistent ‘Strike Hard’ campaign to maintain ‘stability’ and affirmed the importance of the ‘patriotic education’ campaign (http://tb.vtibet.cn/news/2013-09/30/cms360038article.shtml).

Chamdo has been described by the official media as the ‘frontline’ of the ‘patriotic education’ campaigns favored by the Chinese Communist Party as a means of pre-empting further nationalist protest in Tibet, and more repressive measures have been introduced since 2008 to counter dissent and demonstrations. (ICT report, Determination to resist repression continues in ‘combat-ready’ Chamdo, frontline of ‘patriotic education’ – December 2, 2009). Despite the authorities’ emphasis on ‘social stability’; the harsh repressive measures in place, and visits by senior officials from Lhasa to Chamdo, protests and dissent have continued in the region.

Three Tibetan villagers were detained in July in Pashoe (Chinese: Basu) county in Chamdo for refusing to fly the Chinese national flag from their homes; officials had warned that noncompliance would be treated as ‘anti-state activity’, according to Radio Free Asia. (RFA report, Three Tibetans Detained for Refusing to Fly the Chinese Flag – August 1, 2013). In February, Chinese police in Dzogang (Chinese: Zuogong) county in Chamdo rounded up and brutally beat a group of Tibetans following a protest at the start of the Lunar New Year, leaving two with broken bones and taking at least six into custody. (RFA report, Chamdo at Center of Beijing’s ‘Re-Education’ Campaign – July 21, 2013).

Tibetan writer and blogger Tsering Woeser, who is based in Beijing, wrote in June that in Chamdo today, one “does not see any prayer flags but only a field of scarlet red five-starred flags.” In the same article, translated into English by High Peaks Pure Earth, Woeser wrote: “The reason why the work groups have been installed in villages and monasteries in the Chamdo region is to implement the TAR policies of the ‘Nine Haves” (namely ‘to have portraits of the four leaders, to have a national flag, to have roads, to have water, to have electricity, to have a TV set, to have films, to have a library, to have newspapers’); from the end of 2011, on the rooftops of all monasteries, monastery halls and residences of monks as well as on every single farmer’s and herdsman’s house there had to be a five-starred red flag; all monasteries, temples and residences of monks as well as every single farmer’s and herdsman’s house had to hang up portraits of the CCP’s leaders and they had to present these portraits with a Tibetan khata [white blessing scarf], if not people would face political problems. Farmers and herdsmen had to buy the red-starred flags themselves, depending on the quality, one flag could cost between three and six Yuan; if they wanted to replace an old flag with a new one, they also had to pay. Only this year, they started giving flags out for free. The work groups would often go to monasteries and families’ homes to carry out inspections.” (High Peaks, Pure Earth, “Chamdo: Villages and Monasteries are Covered in Five-Starred Red Flags” By Woeser)

Woeser also reported dramatic restrictions in movement of Tibetans in the area, saying that from last year onwards, monks and nuns from almost 500 monasteries in the Chamdo area have been forbidden to go out. In a move likely to be connected to concern over self-immolations, in April, work groups went from house to house in the Chamdo area and confiscated monks’ or herdsmens’ remaining petrol or diesel used for cars and motorbikes.

The Chinese government regards Chamdo as “a strategic bridge between the Tibet Autonomous Region and the neighboring provinces of Sichuan, Yunnan and Qinghai.” (Tibet Daily, April 17). The region has been of particular strategic importance to Beijing since the Communist authorities gained control of central Tibet when Chamdo, eastern Tibet’s provincial capital, fell to the People’s Liberation Army on October 7, 1950.

The current drive to enforce loyalty to the CCP through compelling the display of the Chinese flag is part of the Party’s strategy to intensify control across the TAR as the answer to political ‘instability’. This has led to a dramatic increase in work teams and Party cadres in rural areas of the TAR as well as well-resourced initiatives in the culture and social sphere in Lhasa and other urban areas, sometimes described as ‘cultural replacement activities’. In 2012, the official media announced that more than 20,000 cadres and 5,000 work teams had been selected by the Chinese government to stay permanently in different neighborhoods in the TAR, with other cadres being sent into remote rural areas (Tibet Daily, March 11, 2012).

A Tibetan farmer, who is a village Party member in Shigatse (Chinese: Xigaze) prefecture, told a Tibetan researcher: “My duty is to write a monthly report [that] has to say something about the villagers’ political attitude and their response to the Party’s generous support of development projects in the village. The most difficult thing for me is that I have to give names and details of individuals who are politically suspicious, and who should be the target in my village in order to maintain social stability. […] If I tell the work team about any Tibetan who may be politically suspect, that person will then be a target. […] Some people are detained for a couple of months, and police have investigated their relationships with exile Tibetans. Also I have to make sure that people do not spread any rumours about Dalai [Lama]. […] More recently, we Party members have been told to monitor individuals’ daily activities – to see who is the most influenced by the Dalai, or who is dreaming of independence [Rangzen] and a return to the old Tibet. My responsibility is to make sure there is no chance of splittist activities in the village and to lead villagers in the right political direction.” (ICT report, Storm in the Grasslands: Self-immolations in Tibet and Chinese Policy).

In Lhasa, the TAR authorities developed a campaign of “one Party member to make contact with five families” within communities in the Barkhor area of Lhasa. Tibet Daily reported, “The responsibility of one party member is to deliver party’s important messages to five families’ members on time, to make sure they understand Party policy, to help them and watch them and deeply understand the political thoughts and concepts which influence their lifestyle.” (Tibet Daily, May 26, 2009.)

The mass re-education in the TAR launched in April 2008 has the slogan of “Unity and stability is happiness. Separation [of nationalities] and unrest is disaster.” Under this slogan, the campaign involves requiring ordinary Tibetans to sing revolutionary songs, to give the right answers to questions about Tibet’s past, and to learn rules and regulations of the PRC, including criminal law. Tibetans are also required to oppose the “Dalai clique.”

Bhuchung Tsering, Interim President of the International Campaign for Tibet, said: “The Chinese government’s aggressive clampdown on Tibetans is making the situation more unstable and potentially dangerous. As outlined by the State Department’s Tibet Negotiations Report of 2013, submitted to Congress in May, the Chinese government’s respect for, and protection of, human rights in Tibetan areas deteriorated markedly in recent times. We call on the Chinese government to address the substantial grievances of the Tibetan people through dialogue, and not through the use of intimidation or force.”

Troops moving into Driru in Nagchu