NATIONAL PARKS, RURAL REVITALIZATION?

A REPORT ON THE FUTURE OF TIBET’S PEOPLED LANDSCAPES

NATIONAL PARKS, RURAL REVITALIZATION?

A REPORT ON THE FUTURE OF TIBET’S PEOPLED LANDSCAPES

WHAT IS CHINA’S ‘RURAL REVITALIZATION’ POLICY IN TIBET?

Over the years, under the pretext of uplifting the Tibetan people, Chinese authorities have been using their policy initiatives in Tibet to fulfill their objective of strengthening their hold on them and using Tibet as a resource to meet the needs of ever-increasing Chinese consumer markets. This report focuses on two such policy initiatives, rural revitalization and national parks.

In 2021, at a time when, across China, the coronavirus pandemic forced lockdowns at all levels, bringing life to a virtual standstill, the Chinese authorities nevertheless felt it necessary to announce a plan to intensify meat production across Tibet. That plan is affecting Tibetan society and bringing the Buddhist ethos and value system into direct conflict with the state’s philosophy of modernization.

In April 2021, China’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (MARA) announced a “Five-year action plan to promote the development of beef and mutton production” while in December 2021, the “National Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Industry Development Plan” was issued.

Notably, these announcements came soon after the crash of China’s pork industry caused by an epidemic before the coronavirus. A fast-spreading viral infection had started in 2018 and resulted in the deaths of almost half of China’s hogs, either from disease or compulsory culling to contain the viral spread. As China urgently needed to boost meat supply, and with obvious sources of pork imports, including the USA, off the agenda for political reasons, yak meat from Tibet became a target. The process was put within the strategy for promoting rural revitalization announced by the Chinese government.

Rural revitalization across China is a broad basket of policy initiatives that, in Tibet, primarily means intensifying the slaughter rate of yaks and sheep. Using modernity, efficiency and a reliable cold chain infrastructure connecting Tibet to the urban consumer markets of eastern China as the pretext, the aim is that no sheep should live longer than 12 months, no yak beyond 24 months. The only exceptions are animals kept for breeding.

The MARA “Five-year action plan to promote the development of beef and mutton production” asserts that among its objectives it is to “comprehensively promote rural revitalization” that will impact Tibetan livestock raisers. Additionally, security is a focus, as can be seen from the introduction to the plan, which says it is being announced in order to implement the “Guiding Opinions on the Implementation of Important Agricultural Products Security Strategy.”

The plan does not specifically name Tibet as part of its focus (it does name some other places like Hebei, Inner Mongolia, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Shandong, Henan, Sichuan, Yunnan and Gansu), but its implications for Tibet are clear. The general idea behind the plan is stated as being to “increase the production of beef and mutton meat supply as the goal, co-ordination of pastoral areas, agricultural areas, southern grassy hills and grassy slopes of the region of beef and mutton production.” In short, for Tibet this would mean intensifying the livestock slaughter rate, and the indications are that this is now happening, as outlined in this report.

INTRODUCTION

Over the years, under the pretext of uplifting the Tibetan people, Chinese authorities have been using their policy initiatives in Tibet to fulfill their objective of strengthening their hold on them and using Tibet as a resource to meet the needs of ever-increasing Chinese consumer markets. This report focuses on two such policy initiatives, rural revitalization and national parks.

In 2021, at a time when, across China, the coronavirus pandemic forced lockdowns at all levels, bringing life to a virtual standstill, the Chinese authorities nevertheless felt it necessary to announce a plan to intensify meat production across Tibet. That plan is affecting Tibetan society and bringing the Buddhist ethos and value system into direct conflict with the state’s philosophy of modernization.

In April 2021, China’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (MARA) announced a “Five-year action plan to promote the development of beef and mutton production” while in December 2021, the “National Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Industry Development Plan” was issued.

Notably, these announcements came soon after the crash of China’s pork industry caused by an epidemic before the coronavirus. A fast-spreading viral infection had started in 2018 and resulted in the deaths of almost half of China’s hogs, either from disease or compulsory culling to contain the viral spread. As China urgently needed to boost meat supply, and with obvious sources of pork imports, including the USA, off the agenda for political reasons, yak meat from Tibet became a target. The process was put within the strategy for promoting rural revitalization announced by the Chinese government.

Rural revitalization across China is a broad basket of policy initiatives that, in Tibet, primarily means intensifying the slaughter rate of yaks and sheep. Using modernity, efficiency and a reliable cold chain infrastructure connecting Tibet to the urban consumer markets of eastern China as the pretext, the aim is that no sheep should live longer than 12 months, no yak beyond 24 months. The only exceptions are animals kept for breeding.

The MARA “Five-year action plan to promote the development of beef and mutton production” asserts that among its objectives it is to “comprehensively promote rural revitalization” that will impact Tibetan livestock raisers. Additionally, security is a focus, as can be seen from the introduction to the plan, which says it is being announced in order to implement the “Guiding Opinions on the Implementation of Important Agricultural Products Security Strategy.”

The plan does not specifically name Tibet as part of its focus (it does name some other places like Hebei, Inner Mongolia, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Shandong, Henan, Sichuan, Yunnan and Gansu), but its implications for Tibet are clear. The general idea behind the plan is stated as being to “increase the production of beef and mutton meat supply as the goal, co-ordination of pastoral areas, agricultural areas, southern grassy hills and grassy slopes of the region of beef and mutton production.” In short, for Tibet this would mean intensifying the livestock slaughter rate, and the indications are that this is now happening, as outlined in this report.

MAKING TIBET A RED MEAT MACHINE

Rural revitalization in Tibet is resulting in the intensifying slaughter rate of yaks and sheep. In order to attain the stated policy target of making both beef and mutton production RMB 100 billion (about US$ 14 billion) industries, many interventions are deemed necessary to achieve maximum weight gain of each animal in minimum time to have them ready for slaughter without delay. In the case of yak meat from Tibet, China’s animal production researchers state:

In the traditional mode of breeding, yak meat is supplied seasonally with a long production cycle, unstable quality, and low yield, leading to unsuitable growth status for slaughter and thereby, the supply of fresh yak meat is stopped in the cold season. Therefore, it is crucial to develop a different management system from conventional yak production and upgrade the sustainability of the agricultural output in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and its adjacent regions.[1]

However, maximum weight gain requires feeding penned animals a mix of ingredients typical of intensive feedlot agribusiness worldwide, full of ingredients not locally available in Tibet. The ingredients include maize, soybean meal, wheat bran and flaxseed, with dried distillers grains as roughage. These supplements fatten animals fast but necessitate removing adolescent animals approaching full adult size from their pastures to intensive feedlots to force the pace of maximal weight gain immediately prior to slaughter.

This means a meat industry “with Chinese characteristics,” with many of the slaughterhouses run by non-Tibetans,[2] specializing in the “finishing” of animals bred solely for slaughter, followed by the killing of the animals and the processing of carcasses, with muscle meats butchered and dispatched to distant markets on a cold chain owned by Chinese corporations. Effectively, Tibetan livestock producers are restricted to rearing animals on natural grass pastures only during infancy and adolescence.

“Simple exquisite Tibetan yak meat jerky,” one of the many products of the Qinghai-based Hoh Xil Food Company whose “Kekexili” brand is a major seller of Tibetan yak meat products all over China.

In the cattle industry globally, this role is known as “backgrounding,” the least profitable and most risky of the three separate stages of a modern meat animal’s life, namely breeding genetics, field pasturing and fattening for slaughter. In China’s emergent system, the first and last stages are in Chinese hands, both the veterinary science of breeds designed for consumption and the final weeks of an animal’s life, penned in a feedlot. The life of a yak or sheep on the open range, between these two engineered stages, reduces livestock producers from skilled entrepreneurs to “rural laborers,” their actual designation in official provincial statistical yearbooks.

Traditionally, Tibetan “drogpa” (Tibetan for nomads) know each animal individually and kill only those essential to survival. Equally important, almost all parts of an animal they kill become food or are used some other way, and nomads have special techniques to ensure nothing is wasted. China’s urban consumers, however, are interested only in muscle meats, which are at most 51% of the weight of a slaughtered yak, and may be as little as 45%, depending on yak breed. The rest—blood, internal organs, intestines, horns, bones and skin—are wasted.

Yaks and sheep grazing in Tsolho Prefecture in Qinghai. (Photo: Radio Free Asia / AFP)

The 2021 Ministry of Agriculture Five-Year Plan has specified a goal of producing 6.8 million tons of beef a year by 2025. In addition to its own beef production, China imported a total of 2.688 million tons of beef in 2022, of which 1.105 million tons were from Brazil, accounting for 41% of the total and making it China’s largest foreign beef source, according to the General Administration of Customs of China. But an outbreak of mad cow disease in Brazil in 2023 led to a suspension of imports and put further pressure on intensifying output in places like Tibet.

The combination of recurrent viral epidemics, whether in China or Brazil, the geopolitics of punishing Anglosphere beef producers and rising demand all put pressure on Tibetans to abandon customary modes of production and intensify output bred solely for slaughter.

China’s ambition to make Tibet a meat exporter is not new; it can be found in earlier Five-Year Plans that were implemented only patchily. What is new is the level of investment in agribusiness industry demonstration parks intended to convert Tibetan pastoralists into rural laborers to monetize their companion animals.

As usual, the districts closest to lowland China, with the strongest infrastructure linkages, in Amdo (the traditional northeastern Tibetan province now incorporated into Qinghai, Sichuan and Gansu provinces), are leading the way. A case in point is the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Yak Industry Demonstration Park. According to a state media report in April 2020, the park

which began construction in Huzhu Tu Autonomous County, Haidong City, Qinghai Province, on April 18 (2020), is an important initiative of Qinghai to help the transformation and development of the yak industry, and to promote poverty alleviation and income generation of farmers and herdsmen across the province … Qinghai Province’s Three-Year Action Plan for the Development of Yak and Barley Industry (2018-2020) proposes that by 2020 Qinghai will establish five yak industry demonstration parks, cultivate 20 leading enterprises in the yak industry alliance, establish 110 key ecological animal husbandry cooperatives, and strive to revitalize the yak industry.

Industrialization of yak and sheep production is now intensifying, as part of the general industrialization of Amdo. Early in 2023 the Qinghai legislature approved the official plan for 2023 submitted by the Qinghai provincial government. It called for the creation of a green organic agricultural and livestock product export base. It said four demonstration cities and prefectures and four demonstration counties carried out the first trial and solid implementation. Kungho or Serchen (Chinese: Gonghe) and Tsekhok (Zeku) were listed as pilots for transformation and upgrading, and a national rapeseed industry cluster was created. Gadhe (Gande) Rural Industrial Integrated Development Demonstration Park and Kungho Tibetan sheep modern agricultural industry park were established.

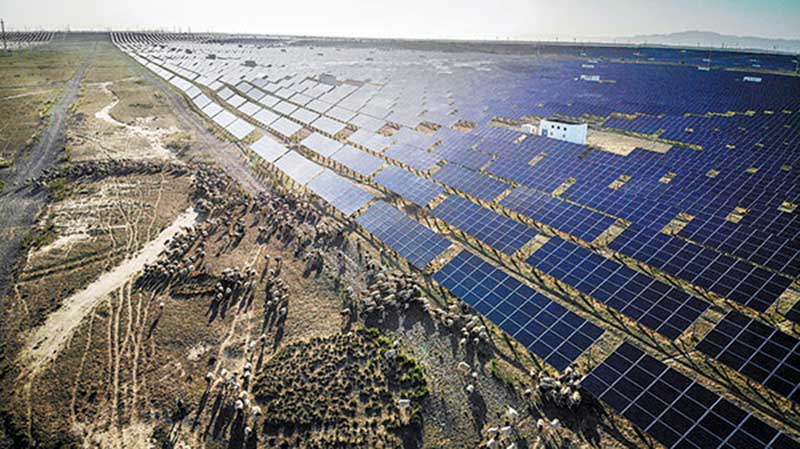

A flock of sheep making their way along a line of solar panels in Serchen (Chinese: Gonghe) county in Qinghai. (Photo: Chinese state media)

The report on the plan said the organic monitoring and certification grassland area has exceeded 100 million mu (a form of measurement equal to 1/15 of a hectare), becoming the largest production base of organic livestock products, organic goji berries and cold-water fish in China. A total of 1,015 certified green, organic and geographical indication agricultural products have been certified. The report on the approval said 8.818 million cattle and sheep were slaughtered, more than 700,000 live pigs were slaughtered, and the production of salmon and trout accounted for one-third of the country’s total.

This is rural revitalization in practice, usually accompanied by the ideological rationale that this constitutes poverty alleviation. Intensifying slaughter rates make remote Tibetan landscapes valuable to China. Until now, only the territorially small enclaves of extraction have been profit centers, plus the Amdo hydro dams where rainbow trout sold as salmon are grown intensively.

Gradually Tibet is becoming an asset class, primarily due to the meat production. The animals originate on the open range and then fattened, slaughtered, butchered, vacuum packed and dispatched to distant urban Chinese markets.

Perhaps the most dramatic is the intervention of Shanghai Municipality in the pastoral landscapes of remote uplands of Golog (Chinese: Guoluo) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Qinghai Province, one of the two entire prefectures constituting the Three Rivers Nature Reserve (Sanjiangyuan).

This capitalization of Tibetan landscapes now contradicts the natural capital valuations of Tibet as national park and ecotourism destination. There are now two competing designations for Tibetan lands, which are not compatible. Production landscapes are seldom accepted as protection landscapes, even if historically Tibetan nomads did manage their lands both sustainably and productively, with wildlife flourishing alongside domestic herds.

As recently as 2015 the entire Golog prefecture produced only 6,535 tons of yak meat, plus 4,453 tons of mutton, making it by far the smallest producer of meat in the whole of Qinghai province.[3] Yet Golog is now one of the major sources of red meat for Shanghai.

Yak meat from Chikdril (Jiuzhi) country in Golog (Goluo) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture being packaged for transportation to Shanghai in 2022.

The expansion of the meat industry also has environmental consequences. Taking the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Yak Industry Demonstration Park located in Tsoshar (Haidong) as an example, the increase in emissions begins when yaks are trucked over 500 kms from the pastures of Golog Jigdril (Jiuzhi) down to Tsoshar. If they are trucked via expressways, the journey is faster but considerably longer. Diesel-powered trucks emit both carbon dioxide and the more toxic nitrogen oxides.

The yaks are offloaded from trucks into feedlots, where they have to get used not only to being confined, but to a complete change of diet, from grazing freely on grass to eating from troughs filled with grains, crop residues, industrial by-products and growth-promoting supplements, including antibiotics, all designed to maximize weight gain in the shortest time. The feed may include barley grown in Tibet but is also likely to be soybeans imported from the US or Brazil, with all the food miles necessary to rail these bulk crops to port, ship them across the Pacific, then truck them deep inland to the Tsoshar feedlot. We are starting to clock up serious emissions.

After months on this diet, the yaks are then slaughtered, butchered, boxed, chilled and sent across China to consumers. Each of these steps causes further emissions. Months being fattened on a high protein diet inevitably result in huge concentrations of manure which, as they ferment, create huge amounts of methane. If feedlot agribusinesses invest in enormous plastic bags that hold the rotting manure, the methane gas can be not only captured but then burned to generate electricity for the factory’s use. Nothing in the Tsoshar meatworks plan mentions any such methane digester.

The Tibetan custom of gathering cow pats by hand—women’s work—drying them and using them as fuel for stoves, seems a lot simpler. Yaks, like all ruminants, eat only grass. Their wastes are mostly cellulose, not at all toxic, excellent for fuelling the hearth of a nomad family tent.

Feedlots are promoted as efficient, not only in speeding up animal growth and slaughter but also in making good use of farm waste such as stalks and straw left behind after a crop has been stripped from the field. This is the argument for trucking adolescent yaks down to a farming district for their last few months of life: access to a cheap but scientifically formulated diet.

In practice, it’s a bit messier. Tsongkha (Huangzhong) in Tsoshar is between Xining and Lanzhou, two big cities rapidly merging into one agglomeration, rather like Chengdu-Chongqing, or the celebrated Jing-Jin-Ji (national capital region) of Beijing, Tianjin and surrounding formerly rural districts. The Xining-Lanzhou megalopolis isn’t there yet, and there are still many agricultural enterprises keen to monetize their waste as feedlot feedstock.

MAKING TIBET A RED MEAT MACHINE

Rural revitalization in Tibet is resulting in the intensifying slaughter rate of yaks and sheep. In order to attain the stated policy target of making both beef and mutton production RMB 100 billion (about US$ 14 billion) industries, many interventions are deemed necessary to achieve maximum weight gain of each animal in minimum time to have them ready for slaughter without delay. In the case of yak meat from Tibet, China’s animal production researchers state:

In the traditional mode of breeding, yak meat is supplied seasonally with a long production cycle, unstable quality, and low yield, leading to unsuitable growth status for slaughter and thereby, the supply of fresh yak meat is stopped in the cold season. Therefore, it is crucial to develop a different management system from conventional yak production and upgrade the sustainability of the agricultural output in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and its adjacent regions.[1]

However, maximum weight gain requires feeding penned animals a mix of ingredients typical of intensive feedlot agribusiness worldwide, full of ingredients not locally available in Tibet. The ingredients include maize, soybean meal, wheat bran and flaxseed, with dried distillers grains as roughage. These supplements fatten animals fast but necessitate removing adolescent animals approaching full adult size from their pastures to intensive feedlots to force the pace of maximal weight gain immediately prior to slaughter.

This means a meat industry “with Chinese characteristics,” with many of the slaughterhouses run by non-Tibetans,[2] specializing in the “finishing” of animals bred solely for slaughter, followed by the killing of the animals and the processing of carcasses, with muscle meats butchered and dispatched to distant markets on a cold chain owned by Chinese corporations. Effectively, Tibetan livestock producers are restricted to rearing animals on natural grass pastures only during infancy and adolescence.

“Simple exquisite Tibetan yak meat jerky,” one of the many products of the Qinghai-based Hoh Xil Food Company whose “Kekexili” brand is a major seller of Tibetan yak meat products all over China.

In the cattle industry globally, this role is known as “backgrounding,” the least profitable and most risky of the three separate stages of a modern meat animal’s life, namely breeding genetics, field pasturing and fattening for slaughter. In China’s emergent system, the first and last stages are in Chinese hands, both the veterinary science of breeds designed for consumption and the final weeks of an animal’s life, penned in a feedlot. The life of a yak or sheep on the open range, between these two engineered stages, reduces livestock producers from skilled entrepreneurs to “rural laborers,” their actual designation in official provincial statistical yearbooks.

Traditionally, Tibetan “drogpa” (Tibetan for nomads) know each animal individually and kill only those essential to survival. Equally important, almost all parts of an animal they kill become food or are used some other way, and nomads have special techniques to ensure nothing is wasted. China’s urban consumers, however, are interested only in muscle meats, which are at most 51% of the weight of a slaughtered yak, and may be as little as 45%, depending on yak breed. The rest—blood, internal organs, intestines, horns, bones and skin—are wasted.

Yaks and sheep grazing in Tsolho Prefecture in Qinghai. (Photo: Radio Free Asia / AFP)

The 2021 Ministry of Agriculture Five-Year Plan has specified a goal of producing 6.8 million tons of beef a year by 2025. In addition to its own beef production, China imported a total of 2.688 million tons of beef in 2022, of which 1.105 million tons were from Brazil, accounting for 41% of the total and making it China’s largest foreign beef source, according to the General Administration of Customs of China. But an outbreak of mad cow disease in Brazil in 2023 led to a suspension of imports and put further pressure on intensifying output in places like Tibet.

The combination of recurrent viral epidemics, whether in China or Brazil, the geopolitics of punishing Anglosphere beef producers and rising demand all put pressure on Tibetans to abandon customary modes of production and intensify output bred solely for slaughter.

China’s ambition to make Tibet a meat exporter is not new; it can be found in earlier Five-Year Plans that were implemented only patchily. What is new is the level of investment in agribusiness industry demonstration parks intended to convert Tibetan pastoralists into rural laborers to monetize their companion animals.

As usual, the districts closest to lowland China, with the strongest infrastructure linkages, in Amdo (the traditional northeastern Tibetan province now incorporated into Qinghai, Sichuan and Gansu provinces), are leading the way. A case in point is the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Yak Industry Demonstration Park. According to a state media report in April 2020, the park

which began construction in Huzhu Tu Autonomous County, Haidong City, Qinghai Province, on April 18 (2020), is an important initiative of Qinghai to help the transformation and development of the yak industry, and to promote poverty alleviation and income generation of farmers and herdsmen across the province … Qinghai Province’s Three-Year Action Plan for the Development of Yak and Barley Industry (2018-2020) proposes that by 2020 Qinghai will establish five yak industry demonstration parks, cultivate 20 leading enterprises in the yak industry alliance, establish 110 key ecological animal husbandry cooperatives, and strive to revitalize the yak industry.

Industrialization of yak and sheep production is now intensifying, as part of the general industrialization of Amdo. Early in 2023 the Qinghai legislature approved the official plan for 2023 submitted by the Qinghai provincial government. It called for the creation of a green organic agricultural and livestock product export base. It said four demonstration cities and prefectures and four demonstration counties carried out the first trial and solid implementation. Kungho or Serchen (Chinese: Gonghe) and Tsekhok (Zeku) were listed as pilots for transformation and upgrading, and a national rapeseed industry cluster was created. Gadhe (Gande) Rural Industrial Integrated Development Demonstration Park and Kungho Tibetan sheep modern agricultural industry park were established.

A flock of sheep making their way along a line of solar panels in Serchen (Chinese: Gonghe) county in Qinghai. (Photo: Chinese state media)

The report on the plan said the organic monitoring and certification grassland area has exceeded 100 million mu (a form of measurement equal to 1/15 of a hectare), becoming the largest production base of organic livestock products, organic goji berries and cold-water fish in China. A total of 1,015 certified green, organic and geographical indication agricultural products have been certified. The report on the approval said 8.818 million cattle and sheep were slaughtered, more than 700,000 live pigs were slaughtered, and the production of salmon and trout accounted for one-third of the country’s total.

This is rural revitalization in practice, usually accompanied by the ideological rationale that this constitutes poverty alleviation. Intensifying slaughter rates make remote Tibetan landscapes valuable to China. Until now, only the territorially small enclaves of extraction have been profit centers, plus the Amdo hydro dams where rainbow trout sold as salmon are grown intensively.

Gradually Tibet is becoming an asset class, primarily due to the meat production. The animals originate on the open range and then fattened, slaughtered, butchered, vacuum packed and dispatched to distant urban Chinese markets.

Perhaps the most dramatic is the intervention of Shanghai Municipality in the pastoral landscapes of remote uplands of Golog (Chinese: Guoluo) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Qinghai Province, one of the two entire prefectures constituting the Three Rivers Nature Reserve (Sanjiangyuan).

This capitalization of Tibetan landscapes now contradicts the natural capital valuations of Tibet as national park and ecotourism destination. There are now two competing designations for Tibetan lands, which are not compatible. Production landscapes are seldom accepted as protection landscapes, even if historically Tibetan nomads did manage their lands both sustainably and productively, with wildlife flourishing alongside domestic herds.

As recently as 2015 the entire Golog prefecture produced only 6,535 tons of yak meat, plus 4,453 tons of mutton, making it by far the smallest producer of meat in the whole of Qinghai province.[3] Yet Golog is now one of the major sources of red meat for Shanghai.

Yak meat from Chikdril (Jiuzhi) country in Golog (Goluo) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture being packaged for transportation to Shanghai in 2022.

The expansion of the meat industry also has environmental consequences. Taking the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Yak Industry Demonstration Park located in Tsoshar (Haidong) as an example, the increase in emissions begins when yaks are trucked over 500 kms from the pastures of Golog Jigdril (Jiuzhi) down to Tsoshar. If they are trucked via expressways, the journey is faster but considerably longer. Diesel-powered trucks emit both carbon dioxide and the more toxic nitrogen oxides.

The yaks are offloaded from trucks into feedlots, where they have to get used not only to being confined, but to a complete change of diet, from grazing freely on grass to eating from troughs filled with grains, crop residues, industrial by-products and growth-promoting supplements, including antibiotics, all designed to maximize weight gain in the shortest time. The feed may include barley grown in Tibet but is also likely to be soybeans imported from the US or Brazil, with all the food miles necessary to rail these bulk crops to port, ship them across the Pacific, then truck them deep inland to the Tsoshar feedlot. We are starting to clock up serious emissions.

After months on this diet, the yaks are then slaughtered, butchered, boxed, chilled and sent across China to consumers. Each of these steps causes further emissions. Months being fattened on a high protein diet inevitably result in huge concentrations of manure which, as they ferment, create huge amounts of methane. If feedlot agribusinesses invest in enormous plastic bags that hold the rotting manure, the methane gas can be not only captured but then burned to generate electricity for the factory’s use. Nothing in the Tsoshar meatworks plan mentions any such methane digester.

The Tibetan custom of gathering cow pats by hand—women’s work—drying them and using them as fuel for stoves, seems a lot simpler. Yaks, like all ruminants, eat only grass. Their wastes are mostly cellulose, not at all toxic, excellent for fuelling the hearth of a nomad family tent.

Feedlots are promoted as efficient, not only in speeding up animal growth and slaughter but also in making good use of farm waste such as stalks and straw left behind after a crop has been stripped from the field. This is the argument for trucking adolescent yaks down to a farming district for their last few months of life: access to a cheap but scientifically formulated diet.

In practice, it’s a bit messier. Tsongkha (Huangzhong) in Tsoshar is between Xining and Lanzhou, two big cities rapidly merging into one agglomeration, rather like Chengdu-Chongqing, or the celebrated Jing-Jin-Ji (national capital region) of Beijing, Tianjin and surrounding formerly rural districts. The Xining-Lanzhou megalopolis isn’t there yet, and there are still many agricultural enterprises keen to monetize their waste as feedlot feedstock.

FROM SUBSISTENCE TO ACCUMULATION

Tibetan pastoralists raise animals on grasslands at altitudes where forests grow only in patches and crop farming is possible only in sheltered valleys. Their successful livestock production, sustained over thousands of years, is an adaptation to a highly unpredictable climate, where there can be snowstorms even in summer. Far from thinking of themselves as poor, the Tibetan drogpa pastoralists have seen themselves as gatherers of the natural annual cycle of animal reproduction, of the food and fibers naturally produced. While the few warmer months require constant hard work, the colder months have been time for leisure, long distance trading expeditions and pilgrimage. This is what Marx called a use economy, in contrast to the capitalist exchange economy in which production is instrumentalized as a step toward obtaining a monetized and commodified objective.

China now expects the nomads of Tibet to shift to an exchange economy, meaning animals are to be raised explicitly and solely for slaughter, for money. While this may be normal in landscapes where beasts on the hoof are just assets awaiting monetization, this is not a customary Tibetan attitude toward fellow sentient beings. For that reason, until very recently, Tibetans have sold animals in the marketplace only when deeply in debt and lacking alternatives.[4]

This deep reluctance to monetize herd animals is usually represented as coming from Buddhist teachings. But a major reason for it is the riskiness of animal rearing and the skills of living off uncertainty. An unseasonal blizzard can block the mountain pass, preventing a herd coming down from summer pasture to the winter flush of grass growth. When much of a herd dies, the only insurance is to have a large herd on the hoof, to aid recovery.

In order to persuade pastoralists to send animals for slaughter on an industrial scale and in keeping with urban demand, requires much thought work by cadres tasked with changing the mindsets of pastoralists for whom their herd is their wealth, their social security, collateral, dowry and insurance against the disasters that can upend fortunes overnight.

Revered Buddhist teachers past and present are famous throughout Tibet as eloquent advocates of abandoning meat, such as Jigme Lingpa in the 18th century, Shabkar Tsokdruk Rangdrol in the 19th, and charismatic teachers such as Khenchen Jigme Phuntsok and Khenpo Sodargye in this century.

FROM SUBSISTENCE TO ACCUMULATION

Tibetan pastoralists raise animals on grasslands at altitudes where forests grow only in patches and crop farming is possible only in sheltered valleys. Their successful livestock production, sustained over thousands of years, is an adaptation to a highly unpredictable climate, where there can be snowstorms even in summer. Far from thinking of themselves as poor, the Tibetan drogpa pastoralists have seen themselves as gatherers of the natural annual cycle of animal reproduction, of the food and fibers naturally produced. While the few warmer months require constant hard work, the colder months have been time for leisure, long distance trading expeditions and pilgrimage. This is what Marx called a use economy, in contrast to the capitalist exchange economy in which production is instrumentalized as a step toward obtaining a monetized and commodified objective.

China now expects the nomads of Tibet to shift to an exchange economy, meaning animals are to be raised explicitly and solely for slaughter, for money. While this may be normal in landscapes where beasts on the hoof are just assets awaiting monetization, this is not a customary Tibetan attitude toward fellow sentient beings. For that reason, until very recently, Tibetans have sold animals in the marketplace only when deeply in debt and lacking alternatives.[4]

This deep reluctance to monetize herd animals is usually represented as coming from Buddhist teachings. But a major reason for it is the riskiness of animal rearing and the skills of living off uncertainty. An unseasonal blizzard can block the mountain pass, preventing a herd coming down from summer pasture to the winter flush of grass growth. When much of a herd dies, the only insurance is to have a large herd on the hoof, to aid recovery.

In order to persuade pastoralists to send animals for slaughter on an industrial scale and in keeping with urban demand, requires much thought work by cadres tasked with changing the mindsets of pastoralists for whom their herd is their wealth, their social security, collateral, dowry and insurance against the disasters that can upend fortunes overnight.

Revered Buddhist teachers past and present are famous throughout Tibet as eloquent advocates of abandoning meat, such as Jigme Lingpa in the 18th century, Shabkar Tsokdruk Rangdrol in the 19th, and charismatic teachers such as Khenchen Jigme Phuntsok and Khenpo Sodargye in this century.

MAKING MORE MEAT OR PROTECTING WILDLIFE, OR BOTH?

China now has competing master narratives mapping the future of rural Tibet as territories of meat production or tourism consumption. These narratives contradict each other with little clarity as to which will prevail.

Arguably, there is room in Tibet for both the productivist and the consumerist visions, since the plateau is so big it could accommodate both. However, this is also a conflict between ministries of the Chinese government, between central and provincial governments, and between a new intention, at the national level, to prescribe policies for the entire plateau that override provincial fiefdoms; versus an entrenched fragmentation of all of what is termed as China’s west, including Tibet, into zones of commodity flow. These entrenched institutional conflicts have not been resolved.

The key competing ministries are Agriculture (MARA) and the ascendant Ministry of Environment and Ecology (MEE). Not only do they propose incompatible visions of the future of rural Tibet, they define the Tibetan Plateau—its extent, needs, problems and utopian prospects—quite differently.

For MARA, the Tibetan Plateau is split, fragmented into the broader geographies of northwest and west China, which includes areas in Qinghai and Gansu; and southwest China, including the Tibet Autonomous Region (which spans less than half of Tibet) and the Tibetan areas of Sichuan and Yunnan. MARA functions hierarchically, through regions, provinces, prefectures and local cadres. MEE imposes direct rule from Beijing, superseding local governments.

MARA maps northwest China’s logistical chain beginning in Xinjiang, then through Qinghai and Gansu and on into inland northern China. The railways, highways, oil and gas pipelines and ultra-high power grids exporting electricity all follow this pathway. For China’s distant urban consumers, it makes little difference, and is of little interest, whether their water, oil, gas, electricity, solar panels, cotton or fish originate in Xinjiang or Tibet; all that matters is that supply is secure. The MARA plan for intensifying meat production follows this logic.

Southwest China, a separate category of governance, starts in the Tibet Autonomous Region, then through Sichuan and Yunnan and on to the provinces of southern China. The MARA plan for accelerating yak and sheep slaughter separates northwest and southwest China, each requiring specific instructions on what is to be done.

A further complication is that MARA allocates little money for the investments, subsidies and cold chain logistics required to implement its vision of Tibet as a river of meat flowing eastward, rather like the actual Drichu (Yangtze) and Machu (Yellow) Rivers, and the flow of hydropower now exported eastward from Tibet. MARA’s vision of making more meat from Tibet depends on MARA appealing for “social capital” investment, meaning private enterprise rather than the state.

MARA exhorts the provincial and local governments of both northwest and southwest China to allocate the necessary subsidies and urges corporate investment. According to Dim Sums, a blog dedicated to Chinese agricultural economics, “The MARA plan features lots of planning and coordination, with a demand that local officials take on their ‘responsibility’ for ‘market basket’ food supplies—that means most of the subsidies are given by local governments. The plan calls for subsidies for breeding farms, protection of indigenous breeds, and artificial insemination; financial transfers to fund programs in cattle- and sheep-producing counties; pilot programs to make bank loans using live cattle as collateral; subsidized insurance; and support for model farms, industrial parks and associated infrastructure.”

Local governments are overloaded with downshifted responsibilities for education, health and social welfare, yet lack a revenue base to finance these major outlays. They are not keen to take on the added responsibility for capitalizing a meat industry.

Basically, this productivist vision of Tibet as a prime source of meat and other animal produce (especially wool) is yesterday’s story, a story of repeated failure to invest significantly in linking Tibetan producers with distant Chinese consumers, despite repeated promises enshrined in successive Five-Year Plans from the national government. In theory, China bases its development strategies on comparative advantage, but not in Tibet.

The Tibetan Plateau. (Image: Rukor)

MAKING MORE MEAT OR PROTECTING WILDLIFE, OR BOTH?

China now has competing master narratives mapping the future of rural Tibet as territories of meat production or tourism consumption. These narratives contradict each other with little clarity as to which will prevail.

Arguably, there is room in Tibet for both the productivist and the consumerist visions, since the plateau is so big it could accommodate both. However, this is also a conflict between ministries of the Chinese government, between central and provincial governments, and between a new intention, at the national level, to prescribe policies for the entire plateau that override provincial fiefdoms; versus an entrenched fragmentation of all of what is termed as China’s west, including Tibet, into zones of commodity flow. These entrenched institutional conflicts have not been resolved.

The key competing ministries are Agriculture (MARA) and the ascendant Ministry of Environment and Ecology (MEE). Not only do they propose incompatible visions of the future of rural Tibet, they define the Tibetan Plateau—its extent, needs, problems and utopian prospects—quite differently.

For MARA, the Tibetan Plateau is split, fragmented into the broader geographies of northwest and west China, which includes areas in Qinghai and Gansu; and southwest China, including the Tibet Autonomous Region (which spans less than half of Tibet) and the Tibetan areas of Sichuan and Yunnan. MARA functions hierarchically, through regions, provinces, prefectures and local cadres. MEE imposes direct rule from Beijing, superseding local governments.

MARA maps northwest China’s logistical chain beginning in Xinjiang, then through Qinghai and Gansu and on into inland northern China. The railways, highways, oil and gas pipelines and ultra-high power grids exporting electricity all follow this pathway. For China’s distant urban consumers, it makes little difference, and is of little interest, whether their water, oil, gas, electricity, solar panels, cotton or fish originate in Xinjiang or Tibet; all that matters is that supply is secure. The MARA plan for intensifying meat production follows this logic.

Southwest China, a separate category of governance, starts in the Tibet Autonomous Region, then through Sichuan and Yunnan and on to the provinces of southern China. The MARA plan for accelerating yak and sheep slaughter separates northwest and southwest China, each requiring specific instructions on what is to be done.

A further complication is that MARA allocates little money for the investments, subsidies and cold chain logistics required to implement its vision of Tibet as a river of meat flowing eastward, rather like the actual Drichu (Yangtze) and Machu (Yellow) Rivers, and the flow of hydropower now exported eastward from Tibet. MARA’s vision of making more meat from Tibet depends on MARA appealing for “social capital” investment, meaning private enterprise rather than the state.

MARA exhorts the provincial and local governments of both northwest and southwest China to allocate the necessary subsidies and urges corporate investment. According to Dim Sums, a blog dedicated to Chinese agricultural economics, “The MARA plan features lots of planning and coordination, with a demand that local officials take on their ‘responsibility’ for ‘market basket’ food supplies—that means most of the subsidies are given by local governments. The plan calls for subsidies for breeding farms, protection of indigenous breeds, and artificial insemination; financial transfers to fund programs in cattle- and sheep-producing counties; pilot programs to make bank loans using live cattle as collateral; subsidized insurance; and support for model farms, industrial parks and associated infrastructure.”

Local governments are overloaded with downshifted responsibilities for education, health and social welfare, yet lack a revenue base to finance these major outlays. They are not keen to take on the added responsibility for capitalizing a meat industry.

Basically, this productivist vision of Tibet as a prime source of meat and other animal produce (especially wool) is yesterday’s story, a story of repeated failure to invest significantly in linking Tibetan producers with distant Chinese consumers, despite repeated promises enshrined in successive Five-Year Plans from the national government. In theory, China bases its development strategies on comparative advantage, but not in Tibet.

The Tibetan Plateau. (Image: Rukor)

PLATEAU SINGULARITY

By comparison, the vision of Tibet as a menu of landscapes available for mass tourism consumption is upcoming, rapidly taking shape, backed by Beijing and for the first time defines the Tibetan Plateau as a singular entity, with national power overriding provincial vested interests.

Recent legislation, enacted in April 2023 and coming into effect on Sept. 1, 2023, places the Tibetan areas under the current People’s Republic of China under one entity, the Tibetan Plateau. National parks are the leading edge of this repurposing of livestock production landscapes as tourism consumption landscapes.

The national parks nationalize prime production land, taking it out of provincial control and turning it over to national ownership so as to redefine their purpose as Chinese landscapes of China’s Tibet, for leisure consumption. Development is redefined as a post-industrial economy based on park ranger employment, tour guiding and hosting—a new economy with specific but limited roles for Tibetans, mostly as rangers enforcing the new land use regulations.

Explicitly included in this new jurisdiction is the entirety of the Tibet Autonomous Region and Qinghai province, plus the Tibetan areas of Gansu, Sichuan and Yunnan, as well as the Arjin mountain uplands of southern Xinjiang (known to Uyghurs as East Turkestan), a large uninhabited area home to wild yaks, Tibetan antelopes, snow leopards and black-necked cranes.

The new law, published as a draft for comment and consultation in 2021, is The Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Ecological Protection Law, and it empowers the Ministry of Environment and Ecology to overrule provincial governments wherever MEE decides that is necessary to achieve its prime goals of protecting China’s water supply and biodiversity.

MEE is a ministry that has been steadily growing in power over the past 15 years, pushing ahead with a mode of environmental authoritarianism commensurate with the generally authoritarian style of the party-state under Xi Jinping.

National parks are intrinsic to this rise in MEE power, for several reasons. National parks are national, owned and administered by the state, which by definition nationalizes what had been under provincial and local jurisdiction. National parks advance national objectives, especially in international arenas, as prime examples of a national will to implement treaty obligations under the various global biodiversity conventions, thus contributing to global reputation and diplomatic reach at the human cost of Tibetans.

Until now, China’s national park system has been compromised by provinciality. A prime example is the Three Rivers Nature Reserve (Sanjiangyuan), meant to protect the uppermost watersheds of the Machu (Yellow), Drichu (Yangtze) and Mekong (Dzachu) rivers, all of which rise in Tibet. However, the Three Rivers Nature Reserve, while big, is entirely within Qinghai province, although the Machu, at the foot of the sacred Amnye Machen mountain range, flows out beyond Qinghai into a vast water meadow of northern Sichuan on the border with Gansu province as it gradually turns back toward the northwest, re-entering Qinghai. The Machu section missing from the national park is the Dzoge Wetlands (Ru’ergai), a wide area of much importance for global seasonal bird migration, which was severely damaged by a program of swamp draining and digging of ditches some decades ago, now being reversed.

China’s new The Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Ecological Protection Law will make it easy for leaders in Beijing to override provincial governments and include all of the uppermost Machu River in a national park.

The recentralization of power in Beijing is represented in China’s soft power projection as proof of China’s prioritization of ecological civilization construction.

PLATEAU SINGULARITY

By comparison, the vision of Tibet as a menu of landscapes available for mass tourism consumption is upcoming, rapidly taking shape, backed by Beijing and for the first time defines the Tibetan Plateau as a singular entity, with national power overriding provincial vested interests.

Recent legislation, enacted in April 2023 and coming into effect on Sept. 1, 2023, places the Tibetan areas under the current People’s Republic of China under one entity, the Tibetan Plateau. National parks are the leading edge of this repurposing of livestock production landscapes as tourism consumption landscapes.

The national parks nationalize prime production land, taking it out of provincial control and turning it over to national ownership so as to redefine their purpose as Chinese landscapes of China’s Tibet, for leisure consumption. Development is redefined as a post-industrial economy based on park ranger employment, tour guiding and hosting—a new economy with specific but limited roles for Tibetans, mostly as rangers enforcing the new land use regulations.

Explicitly included in this new jurisdiction is the entirety of the Tibet Autonomous Region and Qinghai province, plus the Tibetan areas of Gansu, Sichuan and Yunnan, as well as the Arjin mountain uplands of southern Xinjiang (known to Uyghurs as East Turkestan), a large uninhabited area home to wild yaks, Tibetan antelopes, snow leopards and black-necked cranes.

The new law, published as a draft for comment and consultation in 2021, is The Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Ecological Protection Law, and it empowers the Ministry of Environment and Ecology to overrule provincial governments wherever MEE decides that is necessary to achieve its prime goals of protecting China’s water supply and biodiversity.

MEE is a ministry that has been steadily growing in power over the past 15 years, pushing ahead with a mode of environmental authoritarianism commensurate with the generally authoritarian style of the party-state under Xi Jinping.

National parks are intrinsic to this rise in MEE power, for several reasons. National parks are national, owned and administered by the state, which by definition nationalizes what had been under provincial and local jurisdiction. National parks advance national objectives, especially in international arenas, as prime examples of a national will to implement treaty obligations under the various global biodiversity conventions, thus contributing to global reputation and diplomatic reach at the human cost of Tibetans.

Until now, China’s national park system has been compromised by provinciality. A prime example is the Three Rivers Nature Reserve (Sanjiangyuan), meant to protect the uppermost watersheds of the Machu (Yellow), Drichu (Yangtze) and Mekong (Dzachu) rivers, all of which rise in Tibet. However, the Three Rivers Nature Reserve, while big, is entirely within Qinghai province, although the Machu, at the foot of the sacred Amnye Machen mountain range, flows out beyond Qinghai into a vast water meadow of northern Sichuan on the border with Gansu province as it gradually turns back toward the northwest, re-entering Qinghai. The Machu section missing from the national park is the Dzoge Wetlands (Ru’ergai), a wide area of much importance for global seasonal bird migration, which was severely damaged by a program of swamp draining and digging of ditches some decades ago, now being reversed.

China’s new The Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Ecological Protection Law will make it easy for leaders in Beijing to override provincial governments and include all of the uppermost Machu River in a national park.

The recentralization of power in Beijing is represented in China’s soft power projection as proof of China’s prioritization of ecological civilization construction.

TOURISM CONSUMPTION AS PART OF BUILDING A CONSUMPTION-LED ECONOMY

The rebranding of Tibetan pastoral landscapes as national parks fits closely with China’s core strategy for maintaining growth in a middle-income country. The plan is to transition from a low-wage economy driven by statist, top-down infrastructure construction expenditure to an economy led by consumer spending, which is the pattern typical of richer countries. As recent decades of fast economic growth are slowing, economists warn of the “middle-income trap” that, in comparable developmentalist states such as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, stalled ongoing growth for decades. Transitioning away from growth stimulated by state spending to an economy based on the endless proliferation of consumer desires was not easy for Japan, Korea and Taiwan and was achieved only after decades.

China, being officially socialist and having a strong central party-state, could readily stimulate consumer spending by redistributing wealth from rentier owners of multiple apartments and imposing a personal income tax. Although China’s leaders talk vaguely of “common prosperity,” there is little inclination to tax the rich, still less to allocate wealth to the poor and thus achieve a consumer-led economy.

Tourists posing for photos in Lhasa. June 13, 2023. (Photo: Xinhua)

Instead the path to boosting consumption, including tourist consumption of the plateaus of Tibet, follows the habitual strategy of developmentalist states. This means massive infrastructure spending in Tibet and its approaches from lowland China, via high-speed railways, highways, airports, hotels and resort towns. Within a few years, access to Tibet by high-speed rail could be only a few hours away from almost anywhere in China. The dramatic expansion of overland transport access, with heavily subsidized fares, will make it both desirable and feasible to experience “China’s Tibet” directly, an enticing combination of exoticism and domestic securitization.[5]

Currently the tourism industry is heavily skewed toward Tibet’s capital of Lhasa, which, on official statistics, is swamped by domestic tourist arrivals of at least 36 million people per year, nearly all in the warmer months. A lack of plateau-wide basic infrastructure, and of brand management, has so far prevented tourists from straying much beyond Lhasa, and in other portions of the plateau, they are yet to create destinations, still less bundle them into packages targeting specific markets such as red tourism, nature tourism, wildlife spotting, birding, skiing, backroad SUV rallying, pilgrimage tourism, etc. In 2019, the last year before pandemic lockdowns, per capita spending by domestic tourists coming to Qinghai was only RMB 1102 ($160), which the next year dropped to RMB 875 ($122).[6]

The new national parks, which are mostly in Qinghai, are designed to turn this around, a social engineering achievement boosted by lyrical video documentaries extolling China’s Tibet. Desirable, consumable Tibet.

It will take time to install the necessary facilities for a tourism experience with Chinese characteristics that not only generates revenue and employs many Chinese in hospitality, a labor-intensive industry, but also makes Tibetan landscapes Chinese. The momentum is intensifying, the rhetoric of scientific biodiversity protection zoning are in place, the redlining of national parks to supposedly forbid extraction and exploitation is largely complete. Thousands of park rangers have been recruited on the basis of one fit young adult per nomad family, who is now guaranteed lifetime iron rice bowl employment security as long as he (almost always he) enforces China’s land use laws, even if it means evicting his own family from their own pastures.

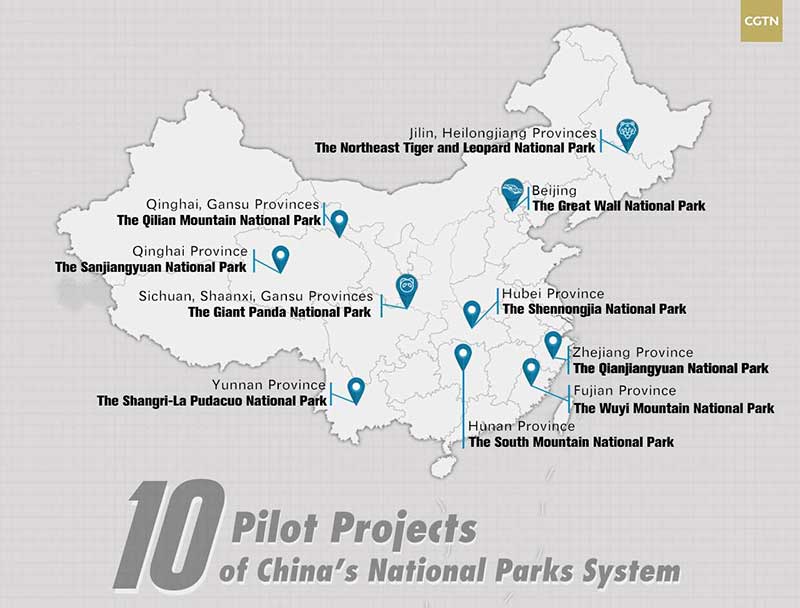

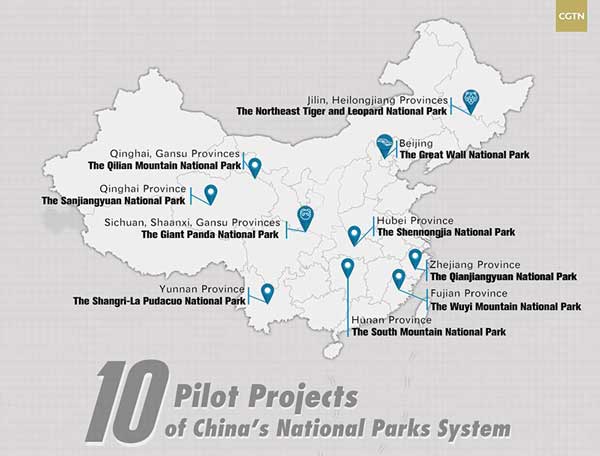

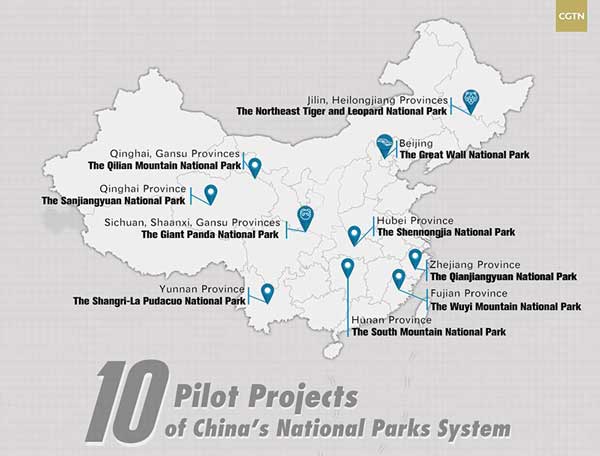

Sanjiangyuan (གཙང་གསུམ་འབུང་ཁུངས་རང་བྱུང་སྲུང་སྐྱོབ་ཁུལ།) and Qilian Mountain (མདོ་ལ་རི།) National Park on the map. (Image: CGTN)

TOURISM CONSUMPTION AS PART OF BUILDING A CONSUMPTION-LED ECONOMY

The rebranding of Tibetan pastoral landscapes as national parks fits closely with China’s core strategy for maintaining growth in a middle-income country. The plan is to transition from a low-wage economy driven by statist, top-down infrastructure construction expenditure to an economy led by consumer spending, which is the pattern typical of richer countries. As recent decades of fast economic growth are slowing, economists warn of the “middle-income trap” that, in comparable developmentalist states such as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, stalled ongoing growth for decades. Transitioning away from growth stimulated by state spending to an economy based on the endless proliferation of consumer desires was not easy for Japan, Korea and Taiwan and was achieved only after decades.

China, being officially socialist and having a strong central party-state, could readily stimulate consumer spending by redistributing wealth from rentier owners of multiple apartments and imposing a personal income tax. Although China’s leaders talk vaguely of “common prosperity,” there is little inclination to tax the rich, still less to allocate wealth to the poor and thus achieve a consumer-led economy.

Tourists posing for photos in Lhasa. June 13, 2023. (Photo: Xinhua)

Instead the path to boosting consumption, including tourist consumption of the plateaus of Tibet, follows the habitual strategy of developmentalist states. This means massive infrastructure spending in Tibet and its approaches from lowland China, via high-speed railways, highways, airports, hotels and resort towns. Within a few years, access to Tibet by high-speed rail could be only a few hours away from almost anywhere in China. The dramatic expansion of overland transport access, with heavily subsidized fares, will make it both desirable and feasible to experience “China’s Tibet” directly, an enticing combination of exoticism and domestic securitization.[5]

Currently the tourism industry is heavily skewed toward Tibet’s capital of Lhasa, which, on official statistics, is swamped by domestic tourist arrivals of at least 36 million people per year, nearly all in the warmer months. A lack of plateau-wide basic infrastructure, and of brand management, has so far prevented tourists from straying much beyond Lhasa, and in other portions of the plateau, they are yet to create destinations, still less bundle them into packages targeting specific markets such as red tourism, nature tourism, wildlife spotting, birding, skiing, backroad SUV rallying, pilgrimage tourism, etc. In 2019, the last year before pandemic lockdowns, per capita spending by domestic tourists coming to Qinghai was only RMB 1102 ($160), which the next year dropped to RMB 875 ($122).[6]

The new national parks, which are mostly in Qinghai, are designed to turn this around, a social engineering achievement boosted by lyrical video documentaries extolling China’s Tibet. Desirable, consumable Tibet.

It will take time to install the necessary facilities for a tourism experience with Chinese characteristics that not only generates revenue and employs many Chinese in hospitality, a labor-intensive industry, but also makes Tibetan landscapes Chinese. The momentum is intensifying, the rhetoric of scientific biodiversity protection zoning are in place, the redlining of national parks to supposedly forbid extraction and exploitation is largely complete. Thousands of park rangers have been recruited on the basis of one fit young adult per nomad family, who is now guaranteed lifetime iron rice bowl employment security as long as he (almost always he) enforces China’s land use laws, even if it means evicting his own family from their own pastures.

Sanjiangyuan (གཙང་གསུམ་འབུང་ཁུངས་རང་བྱུང་སྲུང་སྐྱོབ་ཁུལ།) and Qilian Mountain (མདོ་ལ་རི།) National Park on the map. (Image: CGTN)

WHERE THE NEW NATIONAL PARKS ARE, AND AREN’T

In a system, the whole is more than the sum of its parts. China calls its national parks a system, suggesting their boundaries and human exclusion zones are based on scientific rationality. However the most biodiverse areas of the Tibetan Plateau are in the traditional Tibetan province of Kham, now split between the Tibet Autonomous Region, Sichuan and Yunnan, plus Yushu prefecture in Qinghai, where officially protected status is patchy.[7] The few substantial national parks in Kham fail to include the steep valleys where, on each slope, one can climb from wet subtropics to alpine landscapes in a very short distance, hence the extraordinary biodiversity of the warmest and wettest parts of Tibet.

On the ground, what is branded a system and marketed as a boutique collection of wondrous landscapes is:

- Giant Panda National Park, a belated attempt in Sichuan to connect fragmented panda bamboo forest remnants into a corridor.

- Dola ri/Qilian National Park in Tibet’s farthest north, to protect the mountainous source of irrigation water for the parched Hexi Corridor of Gansu and beyond that the rocket range of Inner Mongolia that receives its only water from sources high in the Dola Ri mountains (Qilian national park).

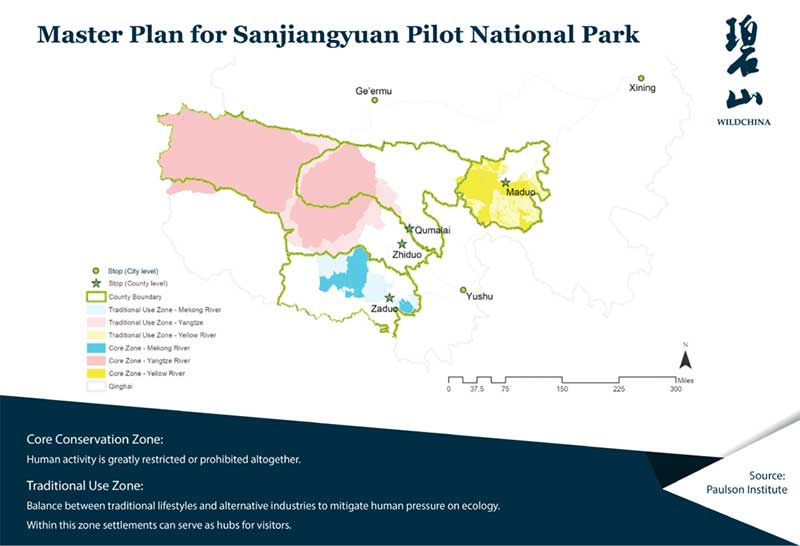

- Three Rivers Nature Reserve (Sanjiangyuan), which turns much of prime Tibetan pasture land eastward as water provisioner to lowland China.

The planned extent of Giant Panda National Park. From Chengdu Municipal Development and Reform Commission. (Reedited: Sixth Tone)

These are the three newest and biggest parks of the national parks “system.” They have little in common, other than plans for mass domestic tourism, and ongoing removal of Tibetan pastoralists to remote towns.

This is the core of the contradiction between the productivist and consumerist versions of Tibetan futures. If Tibet is to fulfill China’s plans for meat production, livestock-producing nomads must remain on their lands, even if they lack land tenure security and are relegated to the risky work of backgrounding. If on the other hand Tibet is to fulfil China’s plans for water security, growing more grass, degradation repair and wildlife protection, then the permanent removal of nomads will continue. These goals are incompatible, especially in the huge area designated as Three Rivers Nature Reserve, “China’s Number One Water Tower,” as it is frequently called.

WHERE THE NEW NATIONAL PARKS ARE, AND AREN’T

In a system, the whole is more than the sum of its parts. China calls its national parks a system, suggesting their boundaries and human exclusion zones are based on scientific rationality. However the most biodiverse areas of the Tibetan Plateau are in the traditional Tibetan province of Kham, now split between the Tibet Autonomous Region, Sichuan and Yunnan, plus Yushu prefecture in Qinghai, where officially protected status is patchy.[7] The few substantial national parks in Kham fail to include the steep valleys where, on each slope, one can climb from wet subtropics to alpine landscapes in a very short distance, hence the extraordinary biodiversity of the warmest and wettest parts of Tibet.

On the ground, what is branded a system and marketed as a boutique collection of wondrous landscapes is:

- Giant Panda National Park, a belated attempt in Sichuan to connect fragmented panda bamboo forest remnants into a corridor.

- Dola ri/Qilian National Park in Tibet’s farthest north, to protect the mountainous source of irrigation water for the parched Hexi Corridor of Gansu and beyond that the rocket range of Inner Mongolia that receives its only water from sources high in the Dola Ri mountains (Qilian national park).

- Three Rivers Nature Reserve (Sanjiangyuan), which turns much of prime Tibetan pasture land eastward as water provisioner to lowland China.

The planned extent of Giant Panda National Park. From Chengdu Municipal Development and Reform Commission. (Reedited: Sixth Tone)

These are the three newest and biggest parks of the national parks “system.” They have little in common, other than plans for mass domestic tourism, and ongoing removal of Tibetan pastoralists to remote towns.

This is the core of the contradiction between the productivist and consumerist versions of Tibetan futures. If Tibet is to fulfill China’s plans for meat production, livestock-producing nomads must remain on their lands, even if they lack land tenure security and are relegated to the risky work of backgrounding. If on the other hand Tibet is to fulfil China’s plans for water security, growing more grass, degradation repair and wildlife protection, then the permanent removal of nomads will continue. These goals are incompatible, especially in the huge area designated as Three Rivers Nature Reserve, “China’s Number One Water Tower,” as it is frequently called.

SECURING AN ‘ECOLOGICAL BARRIER’ FOR CHINA

Administrative map of the Three-River-Source National Park (Image: Three-River-Source National Park Administration 2018)

The primary purpose of Three Rivers Nature Reserve is securitization of lowland water supply, a goal repeated often over many years, which only became more salient as the party-state steadily elevated security to the number one issue. On behalf of the Planning & Design Institute of Forest Products Industry, National Forestry and Grassland Administration, Wei Ling explains what securitization means:

the Three-River-Source National Park Administration set up the Law Enforcement and Supervision Office, which is also titled as both Forest Public Security Bureau of Three -River-Source National Park and Forest Public Security Bureau of Three -River-Source National Nature Reserve. The Law Enforcement and Supervision Office includes 16 police stations and Forest Public Security Bureau of Hoh Xil National Nature Reserve. Each region of the pilot area has integrated forest public security, land law enforcement, environmental law enforcement, grassland supervision, fishery law enforcement and other agencies, so as to set up the Environment Law Enforcement Bureau.[8]

Chinese authorities’ fixation on security now extends well beyond “traditional” security threats such as war, citizen protests and natural disasters, to also embrace “non-traditional” security risks, a vague but all-inclusive category which means just about everything a suspicious, fearful mind can imagine as a problem.

In 2014, Xi Jinping expanded the catalogue of security risks “that integrates elements such as political, homeland, military, economic, cultural, social, science and technology, information, ecological, resource and nuclear security.”[9] Trade disruptions, supply chain uncertainties and pandemics afflicting both farmed animals and humans are all non-traditional security risks warranting central control. Non-traditional security threats include topics such as food security, which could be invoked as a rationale for including meat production from Tibet, as a further anxiety in need of control, in an era when geopolitics disrupts the supply of food and of the imported corn and soybeans China’s fattening feedlots rely on.

Thus there is a possibility that remote Tibetan uplands, where yaks and sheep freely graze, as they have over thousands of years, are now classified as security issues, thus triggering more intensive scrutiny from the state gaze. Right now it is water that is the highest priority security concern, which makes the Three Rivers Nature Reserve the solution.

SECURING AN ‘ECOLOGICAL BARRIER’ FOR CHINA

Administrative map of the Three-River-Source National Park (Image: Three-River-Source National Park Administration 2018)

The primary purpose of Three Rivers Nature Reserve is securitization of lowland water supply, a goal repeated often over many years, which only became more salient as the party-state steadily elevated security to the number one issue. On behalf of the Planning & Design Institute of Forest Products Industry, National Forestry and Grassland Administration, Wei Ling explains what securitization means:

the Three-River-Source National Park Administration set up the Law Enforcement and Supervision Office, which is also titled as both Forest Public Security Bureau of Three -River-Source National Park and Forest Public Security Bureau of Three -River-Source National Nature Reserve. The Law Enforcement and Supervision Office includes 16 police stations and Forest Public Security Bureau of Hoh Xil National Nature Reserve. Each region of the pilot area has integrated forest public security, land law enforcement, environmental law enforcement, grassland supervision, fishery law enforcement and other agencies, so as to set up the Environment Law Enforcement Bureau.[8]

Chinese authorities’ fixation on security now extends well beyond “traditional” security threats such as war, citizen protests and natural disasters, to also embrace “non-traditional” security risks, a vague but all-inclusive category which means just about everything a suspicious, fearful mind can imagine as a problem.

In 2014, Xi Jinping expanded the catalogue of security risks “that integrates elements such as political, homeland, military, economic, cultural, social, science and technology, information, ecological, resource and nuclear security.”[9] Trade disruptions, supply chain uncertainties and pandemics afflicting both farmed animals and humans are all non-traditional security risks warranting central control. Non-traditional security threats include topics such as food security, which could be invoked as a rationale for including meat production from Tibet, as a further anxiety in need of control, in an era when geopolitics disrupts the supply of food and of the imported corn and soybeans China’s fattening feedlots rely on.

Thus there is a possibility that remote Tibetan uplands, where yaks and sheep freely graze, as they have over thousands of years, are now classified as security issues, thus triggering more intensive scrutiny from the state gaze. Right now it is water that is the highest priority security concern, which makes the Three Rivers Nature Reserve the solution.

ALL HUMAN PRESENCE IS A DANGER?

Inherent in the assumptions that necessitated nationalizing the prime pasture lands of Amdo is the presumption that all human presence in protected areas is problematic. Miners, hunters, road builders and pastoralists are all lumped together as alien to the ecosystem, extrinsic to the land, in need of careful management lest they compromise by their presence the core objective of “tuimu huancao” (“retire livestock and restore grassland”), closing pastures to grow more grass. That slogan has governed the uppermost watersheds for decades, eventually evolving into a national park dedicated to grass biomass as the prime indicator of ecosystem restoration success.

Growing more grass is defined as the solution to threats to ongoing water provisioning from Tibet to lowland China; and all that is needed to achieve greater grass growth is to remove grazing herds and their herders. Simple. Hence the formulaic slogan.

In the eyes of the distant party-state, the grassy plateaus of Tibet are fragile, easily degraded by overgrazing by herders ignorant of consequences, which then opens “black beach” spots of erosion that enable burrowing rodents to greatly expand degraded areas by digging up the earth, exposing it to gales and blizzards.

The Chinese gaze defines Tibet by what it lacks, starting with the absence of trees and arable land suitable for ploughing. Tibet lacks warmth and air thick enough to breathe properly. The soils of Tibet are thin, earthquakes and landslides are common, everything is fragile. Pastoralist grazing pressure is inherently risky, as it reduces grass biomass. Every aspect of Tibet, including its soils, rivers, air and culture are pathologized as unnatural, deficient, life threatening.

An official announcing the ban on nomads grazing their livestock on the summer pastures in Guinan, Qinghai. Posted on July 11, 2017. (Photo: Trimleng website)

These negative assumptions have been disproven by many careful scientific investigations, yet they remain foundational to the creation of the national parks. The parks are pitched as the essential links between the pure ice of the glaciers of Tibet and the water needs of downriver consumers. In reality two main rivers, the Drichu (Yangtze) that flows through central China and the over-exploited Machu (Yellow) that flows through northern China, both flow for thousands of miles between glacial source and industrial users, and much of those long journeys are across the grasslands of Tibet. The new national parks extend far beyond the shrinking glaciers, to enclose behind redlines as much as the uppermost 600 miles (1,000 kilometers) of the Machu and much more of the Drichu, which has many major tributaries in Tibet.

File picture of fencing materials dropped off right in front of a lone nomadic family’s tent. (Photo: International Campaign for Tibet)

ALL HUMAN PRESENCE IS A DANGER?

Inherent in the assumptions that necessitated nationalizing the prime pasture lands of Amdo is the presumption that all human presence in protected areas is problematic. Miners, hunters, road builders and pastoralists are all lumped together as alien to the ecosystem, extrinsic to the land, in need of careful management lest they compromise by their presence the core objective of “tuimu huancao” (“retire livestock and restore grassland”), closing pastures to grow more grass. That slogan has governed the uppermost watersheds for decades, eventually evolving into a national park dedicated to grass biomass as the prime indicator of ecosystem restoration success.

Growing more grass is defined as the solution to threats to ongoing water provisioning from Tibet to lowland China; and all that is needed to achieve greater grass growth is to remove grazing herds and their herders. Simple. Hence the formulaic slogan.

In the eyes of the distant party-state, the grassy plateaus of Tibet are fragile, easily degraded by overgrazing by herders ignorant of consequences, which then opens “black beach” spots of erosion that enable burrowing rodents to greatly expand degraded areas by digging up the earth, exposing it to gales and blizzards.

The Chinese gaze defines Tibet by what it lacks, starting with the absence of trees and arable land suitable for ploughing. Tibet lacks warmth and air thick enough to breathe properly. The soils of Tibet are thin, earthquakes and landslides are common, everything is fragile. Pastoralist grazing pressure is inherently risky, as it reduces grass biomass. Every aspect of Tibet, including its soils, rivers, air and culture are pathologized as unnatural, deficient, life threatening.

An official announcing the ban on nomads grazing their livestock on the summer pastures in Guinan, Qinghai. Posted on July 11, 2017. (Photo: Trimleng website)

These negative assumptions have been disproven by many careful scientific investigations, yet they remain foundational to the creation of the national parks. The parks are pitched as the essential links between the pure ice of the glaciers of Tibet and the water needs of downriver consumers. In reality two main rivers, the Drichu (Yangtze) that flows through central China and the over-exploited Machu (Yellow) that flows through northern China, both flow for thousands of miles between glacial source and industrial users, and much of those long journeys are across the grasslands of Tibet. The new national parks extend far beyond the shrinking glaciers, to enclose behind redlines as much as the uppermost 600 miles (1,000 kilometers) of the Machu and much more of the Drichu, which has many major tributaries in Tibet.

File picture of fencing materials dropped off right in front of a lone nomadic family’s tent. (Photo: International Campaign for Tibet)

CHINA’S ABUNDANT WATER TOWER IN TIBET

In reality, the flow of water from Tibet to China is increasing, both because of glacier melt induced by climate change, and because of rainfall and snowfall increase, especially in northern Tibet. This is also due to climate change weakening the monsoons and strengthening the westerly winds that carry moisture high in the jet stream. This precipitates back to earth due to the altitude of the plateau as it blocks jet stream flow. China is reaping a dividend of increasing streamflow from Tibet, directly attributable to China’s emissions as the world’s biggest emitter of climate-heating gasses. According to the measurements of Chinese scientists, the boost in streamflow began at the start of this century, long before the national parks were declared.

The 21st century increase in rain and snow in northern Tibet not only reverses a slow drying trend of past centuries, it also reverses the desertification of northeast Amdo, which was blamed on ignorant nomads rather than climate change induced by emissions from the factories in eastern China. This century’s rainfall trend in Tibet undercuts the rationale for national parks as essential to downstream water security. Until the glaciers are gone, decades from now, China is reaping a water flow dividend.[10]

The argument for national parks that reduce resident human presence by traditional custodians is that the only way to safeguard secure water supply is to grow more grass, and grazing by yaks and sheep is by definition a security threat. This ideological proposition ignores abundant evidence that Tibetan pastoralists took great care to ensure grazing pressure was always moderate, not heavy, and skilled grazing management strategies of Tibetan nomads maximise biodiversity, while removing grazing reduces biodiversity.[11]

At the highest level, China persists in ignoring the mounting scientific evidence that China’s downstream water stress is due to industrial and agricultural over-use and is not solved by ongoing removal of nomads from national parks zoned as human exclusion areas.

The waters of Tibet have never needed securitization before. The purity of the waters of the three large rivers—Machu, Drichu and Dzachu—rising in Tibet has never before been questionable, in need of protection and ecological restoration. The hundreds of miles of Tibetan grassland, wetland and water meadow those rivers meander through have never been seen as problematic, requiring elaborate planning controls imposed by a distant capital. The absurdity of governing Tibetan rivers from afar, stamping water with a seal proclaiming them 水shui (Chinese for water) was acted out by artist Song Dong in the Kyichu (river) in Lhasa in 1996. Despite his energetic efforts, he left no impression.

CHINA’S ABUNDANT WATER TOWER IN TIBET