The hostile forces have colluded with the clique of the fourteenth Dalai Lama, and […] have tried all means to contend for the battlefield, popular feeling and the common people, thus, all their efforts have made Tibet the teeth of the storm in the struggle of the ideological realm.”

– Tibet Autonomous Region Party Secretary Chen Quanguo[1]

Tightening oppression in Tibet, including a new emphasis on ‘counter-terror’ measures, has created a more dangerous political environment for Tibetans in expressing their views.

As a result a new generation of Tibetans is paying a high price with their lives for peaceful expression of views in a political climate in which almost any expression of Tibetan identity or culture not directly sanctioned by the state, no matter how mild, can be characterized by the authorities as “splittist” and therefore “criminal.” Definitions of what constitutes “criminal” activity are deliberately opaque, giving leeway for lower-level officials and security personnel to apply harsh penalties.

This report documents the cases of young generation intellectuals, artists, bloggers, writers and singers who have faced life-altering consequences of torture and imprisonment for conveying their views or simply singing songs. It details the cases of 11 imprisoned writers and intellectuals and 10 singers who have faced persecution and imprisonment, including the following:

- Lo Lo, a Tibetan singer, is currently seriously ill in prison after he was sentenced to six years for singing songs including “Raise the Tibetan flag, children of the Snowland”.

- The whereabouts of Tibetan blogger, Shokjang, known for his perceptive insights into contemporary policies, is unknown after his detention in March. A friend wrote: “When a mind or voice like his is stifled and silenced for a time or forever, it is the unpropitious cloud of darkness and oppression that ushers a reign of terror in the land.”[3]

- Thamkey Gyatso, a monk who was a prolific writer for literary magazines, is paralysed and unable to walk following torture in detention during his 15 year prison sentence.

- Kalsang Yarphel, sentenced to four years for his songs, which included lyrics urging unity among Tibetans, and for Tibetans to speak Tibetan.

“The teeth of the storm” outlines the political context of their imprisonment, and documents how despite the intensified dangers, Tibetans are continuing to take bold steps in asserting their national identity and defending their culture. Tibetan popular music and literature has become an artistic means through which Tibetans define their identity, and as a means of countering the Chinese state.[4]

I. The importance of artistic expression and the political context

In Tibet today, writers, singers and artists play an increasingly important role in the broader community. They express a sense of loss, dispossession and grief about the situation of Tibetans due to China’s repressive policies and the current restrictions. They also celebrate a shared national and cultural identity, encourage a sense of solidarity, and express hope for the future.

The Chinese state has long been aware of artistic expression as a means of influence both in the interests of the Party and against it, and the authorities in Tibetan areas seek to undermine their popularity and influence. Mao Zedong famously referred to a “cultural as well as an armed front”, saying that “[Literature and art] can act as a powerful weapon in uniting and educating the people while attacking and annihilating the enemy.”[5]

More recently, the new space for artistic and other expression of the internet is singled out as being of particular concern in an article published by the People’s Liberation Army Daily on May 12: “Since ancient times, those who won people’s minds won all under heaven. Now, the main battleground to contend for people’s minds has shifted towards the Internet.”[6]

State censorship and suppression of free expression is widespread across the PRC, but since the protests broke out across Tibet in March, 2008, the Chinese government has strengthened attempts to impose an information blackout across Tibet. Leave alone having the freedom to peaceful expression of political opinions, today any public assertion of Tibetan identity even when they are non-political and religious & cultural in nature is being looked upon suspiciously and oftentimes not permitted. Penalties for even low-level information sharing are among the worst in the world.

The Chinese suppression of Tibetan freedom of expression is most visible in the form of the clampdown against any act of reverence to their spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama. Even though the Dalai Lama ruled over only around half of the traditional Tibetan area politically before the Chinese Communist takeover, historically, Tibetans from all over Tibet regard him as their spiritual leader. They have had no problems expressing this aspect of their relationship, most concretely in the possession and display of the Dalai Lama’s portraits in the monasteries and homes.

The dangers have worsened in the context of the new drive against counter-terror. Together with the National Security Law that is expected to be implemented this year, a proposed new law currently in draft form outlines a counter-terrorism structure with vast discretionary powers. The conflation of “terrorism” with religious “extremism” in the law gives scope for the penalization of almost any peaceful expressions of Tibetan identity, acts of non-violent dissent, or criticism of ethnic or religious policies.[7] The draft law represents an escalation in an expansive ‘counter-terrorism’ drive launched by the government following the killings in Xinjiang that has increasingly targeted Tibetans, despite the absence of any violent insurgency in Tibet.[8]

II. The cultural battleground

In November 2013, the Party Secretary of the Tibet Autonomous Region Chen Quanguo wrote an article for a Party journal about the ‘anti-separatist’ struggle that distilled the Chinese Communist Party’s current approach on Tibet, including the drive to obliterate free expression.[9]

“As an ethnic border region, Tibet is at the forefront of the anti-separatist struggle,” Chen wrote in the journal “Quishi” in November, 2013 (“Seeking Truth”). “At present, the exchanges, mingling and contestation among various ideology and culture have become more frequent, in particular, the hostile forces have colluded with the clique of the fourteenth Dalai Lama, and have considered Tibet as a key area for infiltration and separatist activities and as the main battlefield for sabotaging and causing disturbances. They have tried all means to contend for the battlefield, popular feeling and the common people, thus, all their efforts have made Tibet the teeth of the storm in the struggle of the ideological realm. Therefore, we have fully realised the extreme importance and urgency of strengthening the work of the ideological realm. We should […] truly shoulder the important political responsibility entrusted to us by the Party and the people.”

The CCP’s imperative to strength the work of the ‘ideological’ realm emerges from its strategic and economic objectives in Tibet. The Chinese authorities prioritise infrastructure construction and resource exploitation as key elements of its strategies to integrate Tibet into the PRC, casting Tibetan support for the Dalai Lama and protection of Tibetan national identity as obstacles to its elaborate ambitions to re-shape the Tibetan plateau for its own purposes and ensure the domination of the Party.

Scholar Tsering Topgyal explains how this ‘hyper-securitization’ of Tibet is institutionalized in practice as follows: “Once an issue becomes associated with open-ended threats like ‘local nationalism’, ‘separatism’, or extremism and gets defined as a threat to any of these referent objects, it enables the Chinese officials at any level of the government to deal with that issue with harsh measures that could be interpreted as violating even the provisions of the Chinese Constitution and the [Regional Ethnic] Autonomy Law.”[10]

The Tibet issue is characterized not only as a “core issue” of the PRC’s territorial sovereignty, but also as a matter of national security, on the frontline of China’s struggle to safeguard national unification.[11] In this context, the cultural and ideological struggle against the ‘Dalai clique’ has been linked specifically with national security. TAR Party chief Chen Guangguo asserted in 2012 that restrictions on communications and social media in Tibet are necessary in order to maintain “national security”.[12] Since then, Xi Jinping has put himself in charge of a National Security Committee that was established during the Third Plenum of the CCP, with one of its main priorities being cyber-security and scrutiny of social media.

These developments represent a consolidation of the “teeth of the storm” struggle not only against collective action such as protests or demonstrations, but also in the Party’s attempts to circumscribe or shut down online civil society. It is a very serious undertaking for the Party state, meaning that no target is too small or too marginal to be worthy of scrutiny in the ‘battlefield’ of public opinion and political authority.

Monk, blogger and environmentalist Kunga Tsayang is one of those individuals who challenged the Party state line on social media. After authoring several essays, including: “Who Is the Real Splittist?”, “Who Is the Real Destroyer of Stability?”, “We Tibetans are the Real Witnesses”, and “Who Is The Real Instigator of Protests?”, Kunga Tsayang was sentenced to five years in prison on November 15, 2009.[13]

An account of his interrogation published by the Tibetan Center for Human Rights and Democracy is instructive. TCHRD, based in Dharamsala, was told that three specific essays had been singled out by Kunga Tsayang’s interrogators. When asked what he meant by the essay on Lhasa, he said that while it was true that the government had built a new railway, and new housing, both spiritual and secular life in Lhasa have deteriorated. When Kunga Tsayang was questioned on the contents of his essay, “Where is Our Government?” he responded that the Chinese government had introduced many constitutional provisions, laws and regulations, however, for the autonomous areas, these constitutional provisions had not been implemented.

It is rare to gain such specific insights into the specific lines of enquiry taken by local interrogators against intellectual expression, but the information from Kunga Tsayang points to the often precise nature of the ideological battleground and the authorities’ awareness of the importance of social media in influence over public opinion.

III. A remarkable cultural resurgence and the courage of a new generation

My joy is Buddhism

My joy is the tradition of Tibet

My name is the religious land of Tibet

As a Tibetan, I learn Tibetan

As a Tibetan, I learn Tibetan”– Lyrics of a song by a popular Tibetan singer[2]

Given the harsh penalties outlined above for expressing oneself in Tibet today, it is all the more remarkable that there has been a resurgence in expression of Tibetan national, religious and cultural identity.[14]

Well-known writer, blogger and poet Tsering Woeser wrote: “To this day, records and critiques written in Tibetan, Chinese and many other languages keep flooding out, and in particular books, magazines, essays and lyrics written in the mother language are emerging. Tibetans living under the Chinese political system are breaking through the silence, and there are more and more instances of these voices being bravely raised, which is encouraging even more Tibetans.”[15]

There has been an unprecedented focus on pan-Tibetan solidarity, without regional differences that have often been the cause of tensions in the past. Some of the lyrics of one of the most popular Tibetan songs, “The Sound of Unity” by Tibetan group Sherten are: “We are the keepers of herds in the nomadic lands of the upper reaches/We are the farmers in the valleys of the low lying lands/O ruddy faced Tibetans/O Tibetans! Unite, unite/If you think of our destiny of tears and laughter/O Tibetans! Unite, unite/Three provinces unite”.[16]

Enmeshed with the anguish of oppression in Tibet is the pain of separation from an exiled leader, the Dalai Lama, and absence of fellow Tibetans in the exile diaspora – a common theme of writings and song in contemporary Tibet.[17]

Writers and singers, using print and the new space accorded by the internet to upload tracks or blogs, have been at the forefront of this vibrant cultural and literary resurgence since 2008, grounded in a strong sense of Tibetan identity. Many of them appear to be motivated by the view that artistic expression should serve people, and bring them together, as the Dalai Lama has expressed when he said last year: “Generally, I believe artists and musicians alike, have the responsibility to serve or to help humanity… So therefore, I think it is the responsibility of all entire humanity, particularly you as a musician or artist, through your own profession, give people hope, a new idea, a sense of responsibility.”[18]

Tibetan scholar Lama Jabb writes: “Popular songs provide a channel for voicing dissent, while also reinforcing Tibetan national identity by evoking images of a shared history, culture, and territory, bemoaning the current plight of Tibetans and expressing aspirations for a collective destiny.”[19]

In daring to refute China’s official narratives on Tibet, this new generation of Tibetans represents a more complex challenge to the ruling authorities. In many cases, while the dangers have intensified, the messages from writers and musicians have become bolder and less ambivalent. “[Tibetan contemporary] songs have progressively become more audacious and expressive over the decades,” writes Lama Jabb.[20] “The coded language and ambiguity of earlier songs have given way to more explicit expressions of nostalgia for past glories and aspirations for their emulation.”

Tibetan singer Tsewang Lhamo is one of many popular artists to focus on the importance of Tibetan language in her songs. In “Tibetan Soul”, she sings: “My life force is the snowy mountains/The blood in my body is the pure water of the snow/My name is land of snows/As a Tibetan, I speak Tibetan As a Tibetan, I speak Tibetan”.[21] Kalsang Yarphel, a Tibetan singer who is serving four years in prison, also sang about the importance of the mother tongue, singing: “Tibetans, we learn Tibetan, speak Tibetan, it is our duty to do so”.

The new forms of cultural expression have been accompanied by a increase in collective endeavours to speak and write in Tibetan, with the formation of “pure land” language groups.[22] But this can also have harsh consequences. A new set of regulations issued in Rebkong (Chinese: Tongren), Qinghai, warn that “protecting the mother tongue” can now even be “illegal”. The measures, imposed this year, were the latest indicator of the political climate of impunity and the severity of repressive measures being imposed across Tibet, particularly in areas where there have been peaceful protests or self-immolations, such as Rebkong county in eastern Tibet. Point Four of the Rebkong measures targets Tibetans who have been involved in simply speaking their own language and protecting the environment, stating that one of the 20 “illegal activities” are “organizing illegal groups and illegal movements in the name of ’protecting the mother tongue’, ‘environmental protection’, ‘literacy classes’ etc.”[23]

Czech novelist Milan Kundera wrote: “The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.” Through their writings, many Tibetans seek to come to terms with, and preserve the memory of, a shared history. The Tibetan poet Ombar writes: “One life, two lives, three lives…one hundred lives/Incessantly lost and are losing/Therefore we should lament, we should commemorate/Within the crevices of history we should never forget”.[24]

Although less well-known outside the PRC than high-profile Chinese dissidents such as Liu Xiaobo and Hu Jia, many of the Tibetan intellectuals named in this report are famous among Tibetans, and are also enduring long prison terms for peaceful expression.

The level of violence directed at Tibetan political prisoners is frequently extreme and results in Tibetans being left with severe scars following a period of detention, including paralysis, the loss of limbs, organ damage, and serious psychological trauma.[25]

Restrictions are not only applied to the artists themselves, but also those involved with any ‘cultural production’. In 2009, Lhasa’s deputy police chief announced in a press conference that they had just detained 59 “rumour-mongers” for “inciting ethnic feelings” – through the illegal downloading of ‘reactionary’ songs from the internet.[26]

Similarly, the Chinese authorities seek to extend censorship beyond the PRC’s borders. On April 2, 2011, China’s State Council Information Office issued a directive for websites to delete a humorous and popular Youtube video of a song by a Swiss-based Tibetan about meat dumplings, Shapaley. The ruling stated: “All websites, particularly those with video and audio channels, are to look for and delete the song Meat Pancake (Roubing) by Gamahe Danzeng.” While it has a light-hearted tone, the song reflected Tibetan values of respect for elders (“It is good to obey your parents/If your grandmother tells you to buy vegetarian/If your grandpa likes you to pass his walking sticks/You had better do it”) as well as pride in being Tibetan, and determination to protect one’s Tibetan cultural identity, even in exile. “Hey, wake up/even if you live in the West, do not forget that Tibet is where you come from/speak Tibetan and write Tibetan/be proud to be Tibetan.”[27]

Artists and singers in prison: cases

Musicians and singers

KELSANG YAPHEL (Singer)

Former political prisoner Lhamo Kyab said that Kalsang Yaphel had helped organise Lhasa-area concerts called Khawai Metok, or Snow Flower, in which he sang an upbeat, catchy song titled ‘Fellow Tibetans’.[28] After the concert, the Chinese authorities raided shops and confiscated the DVDs, although copies had already been widely distributed in Tibetan-populated areas of China’s Qinghai, Gansu, Sichuan, and Yunnan provinces and footage of Kalsang Yaphel singing one of the songs was uploaded onto Youtube.[29] Lyrics include: “Tibetans! We must practice written & spoken Tibetan language/It is our duty to grasp the spoken and written Tibetan/Tibetans! It is our duty to grasp the spoken and written Tibetan/Tibetans! We must unite, must unite/All the three provinces must unite/Following the idea of unity/Tibetans!”

According to Tibetan sources, he is now being held at Mianyang Prison in Sichuan.

Kalsang Yaphel is a father of three from Kanlho Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture (Ch: Gannan) in Gansu Province. He was first arrested in Lhasa where he ran a guest-house in July 2013, and the guest-house was later shut down. Kalsang Yaphel is also believed to have been fined 200,000 yuan (over 32,000 USD). He was detained in Chengdu, the provincial capital of Sichuan, for almost a year and a half before being sentenced to four years.

PHULJUNG (Singer)

Amchok Phuljung, age 30, released a number of songs that praised both the Dalai Lama and the Sikyong in exile, Lobsang Sangay. He was detained in August, 2012, in Barkham county in Sichuan’s Ngaba (in Chinese, Aba) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, and it is not known how long he was held in prison.

Amchok Phuljung, age 30, released a number of songs that praised both the Dalai Lama and the Sikyong in exile, Lobsang Sangay. He was detained in August, 2012, in Barkham county in Sichuan’s Ngaba (in Chinese, Aba) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, and it is not known how long he was held in prison.

In one song, Amchok Phuljung describes the Tibetan people as a “kind and just race” and urges them to resist China’s domination by speaking “only pure Tibetan” and by “uniting and working together.”

A Tibetan source from Amdo said: “Phuljung is gifted with a wonderful voice and has been very courageous in expressing the well-being of Tibetan people under Chinese Communist rule through his music. Tibetan people inside Tibet have referred him ‘the singer with dignity’, and his albums have been greatly appreciated by Tibetan audiences.”

Phuljung is known as Amchok Phuljung because he is from the Amchok township of Kakhok (or Changchu) County (Chinese:: Hongyuan), Ngaba (Chinese: Aba) Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture in Sichuan Province (the Tibetan area of Amdo).

LO LO (Singer)

There are fears for the health of singer Lo Lo, who is in prison following the release of his album entitled ‘Raise the Tibetan flag, Children of the Snowland’.

There are fears for the health of singer Lo Lo, who is in prison following the release of his album entitled ‘Raise the Tibetan flag, Children of the Snowland’.

Lo Lo, who is currently serving six years of imprisonment in a Chinese jail in Qinqhai is reportedly in very poor health, and his family have not been allowed to see him, according to exile Tibetan media.[30]

Lo Lo, who is 30, was first detained in April 2012, and according to sources was tortured and interrogated for some weeks, with officials asking him many questions about the lyrics of his songs and his performances. He was later released but then detained again in his home town, Dhomda in Jyegudo (Yulshu), Qinghai, and sentenced to six years on February 23, 2013.

“His detention came months after he had released his album titled, “Raise the Flag of Tibet, Sons of the Snow,” said Lobsang Sangyal, an exile monk at a monastery in South India, told Radio Free Asia.[31] The lyrics of the title track include: “With a realized understanding of our objectives, raise the flag of Tibet, sons of the snow.”

Lo Lo’s album, “Raise the Tibetan flag, Children of the Snowland” also included a song about the Panchen Lama. According to Tibetan sources, a monk from Nyatso Zilkar monastery in Jyekudo named Lobsang Jinpa was accused of writing the lyrics, and also arrested. He is believed to be serving five years at the same labor camp as Lo Lo in Xining, the provincial capital of Qinghai.

Lo Lo’s family were not informed of his whereabouts following his arrest and it was only after many weeks of trying to find him that they established his likely place of detention. The family still do not know the charges against him.

THINLEY TSEKAR (Singer)

Thinley Tsekar, a popular singer in his early twenties, was detained in November, 2013, and sentenced to nine years in prison, according to Tibetan sources on December 19, 2013.

Thinley Tsekar, a popular singer in his early twenties, was detained in November, 2013, and sentenced to nine years in prison, according to Tibetan sources on December 19, 2013.

Thinley Tsekar is from the restive area of Driru (Chinese: Biru), Nagchu (Naqu) prefecture of the Tibet Autonomous Region, which has been targeted by a broader political campaign and paramilitary crackdown following Tibetan resistance against the authorities’ efforts to compel Tibetans to display the Chinese national flag from their homes.[32]

Thinley Tsekar was arrested by the local authorities on November 20 2013 while he was studying to apply for a driver’s license in Driru town. This followed a large Tibetan demonstration which erupted in Driru to protest against mining operations which were damaging the local environment. After that a number of local people were detained by local authorities. It is not clear whether Thinley Tsekar had participated in the protest or not, but Tibetan sources say that in Driru it is believed that his arrest was linked to his CD, ‘Chain of Unity’.

Thinley Tsekar is a well-known singer in Driru who “used to express the pain and suffering of Tibetan people through his songs”, according to the Tibetan Center for Human Rights and Democracy. He is from Serkhang village in Driru township. Since his sentencing, his family members including his elderly mother, wife and child, do not know where he is being held or how he is.

GONPO TENZIN (Singer)

His songs were steeped in references to Tibetan culture, literature and language, and the song believed to be connected to his detention was called ‘No Losar [Tibetan New Year] for Tibet’. This is a reference to the time when Tibetans decided to mark Tibetan New year by mourning as an expression of respect for those who had passed away or been imprisoned following the 2008 protests.[35] Gonpo Tenzin’s popularity increased after the song became a huge hit, according to Tibetan sources.

SHAWO TASHI

Shawo’s album, ‘Distant Father’, believed to be a reference to the Dalai Lama, was deeply appreciated by Tibetans, according to Tibetan sources, and local authorities restricted sales of the CD in Tibet.

Shawo Tashi, from Dowa (Chinese: Duowa) township, was detained in November, 2012, following a wave of self-immolations and protests in Rebkong, and is believed to be detained in a labor camp in Xining.

The Tibetan Center for Human Rights and Democracy reported: “Shawo Tashi is known for his great love and respect for Tibetan culture and language. Since childhood, he has a deep interest in traditional Tibetan music; he was especially adept at playing mandolin and dranyen, a Tibetan lute. Among the music albums he has released so far, one titled “Father in Distant Land” (Tib: Gyang Ring Ghi Phalo) is one the most popular music DVDs. Sources say he had sung many songs celebrating Tibetan identity and culture, and his songs are popular among local Tibetans.”[36]

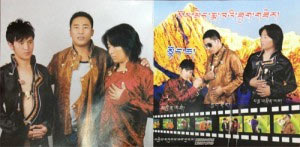

CHAKDOR and PEMA THRINLEY

Cover photo of the album shows Chakdor (standing in the middle in gold-colored shirt), Pema Trinley (in maroon shirt on right) and musician Khenrap (on left in black shirt). (TCHRD)

One of Chakdor’s songs refers to the Chinese government’s exploitation of Tibet’s natural and mineral reserves, with the lyrics “Our precious minerals/Being deceptively destroyed by authorities/Making this sacred land hollow/It is a force against our will”.[39]

Chakdor and Pema Thrinley are being held in Mianyang prison in Sichuan province. Reports vary as to whether they were sentenced to two years imprisonment[40] or four.[41]

PEMA RIGZIN

In “A Song to Remember the Snowland,” Pema Rigzin sings: “I recall this snow-land of Tibet/The land in possession of precious Buddha’s compassion/The land enshrined by the embodiment of Bodhisattvas/The land, seat of (our) saviour Lama.”

GEPEY

Noting his detention on social media, Tibetan blogger Woeser wrote that “Gepey, who had disappeared for so long, finally resurfaced. But before we had time to celebrate his independence we heard news of his arrest.”[45] He has subsequently kept a low profile. Video of his May 2014 performance was uploaded to the internet, showing Chinese police wearing helmets and body armor moving through the crowd as Tibetans try to give Gepey khatas, white Tibetan ceremonial scarves.[46]

Tibetan writers and intellectuals in prison[47]

GARTSE JIGME

A Tibetan monk, Jigme Gyatso, more well known as Gartse Jigme based on the name of his monastery in Amdo, was sentenced to five years in prison on May 14, 2013, after writing two books on the situation in Tibet and the suffering of Tibetan people, according to information from Tibetans in exile. Gartse Jigme’s third book, which was seized by police from the publishers’ before printing, includes a discussion on the self-immolations in Tibet and Chinese policy, sources say.

Gartse Jigme Gyatso was detained by police in his room at Gartse monastery in Tsekhog (Chinese: Zeke Xian) county in Malho (Chinese: Huangnan) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture), Qinghai on January 3, 2013 and taken to Xining. Gartse Jigme, who began his writing career in 1999 after study for a monastic degree, was sentenced to five years in prison on May 14, 2013. The exact charges against him are not known.

Gartse Jigme had been under constant surveillance and detained a number of occasions since the publication of his second book in 2008, called ‘Courage of the Tibetan King’ (‘Tsanpoe Nyingtop’ བཙན་པོའི་སྙིང་སྟོབས), a collection of essays in the Tibetan language about the political situation in Tibet since the March, 1959 Uprising and the protests that swept across Tibet in 2008. In one essay, translated into English by ICT, he wrote: “When I think about these things, it seems to me that the political protests in many places in central Tibet, Kham and Amdo this year [2008] were not organized by the Dalai Lama but were the inevitable expression of the pain stored up for so long in the minds of Tibetans young and old.”

Despite the danger, Gartse Jigme began work on a third book, also addressing serious questions about the situation inside Tibet. This time, the authorities seized the books while they were at the publishers, and attempted to prevent any distribution. Even so, some copies of the book have been circulating underground. Both texts are circulating in exile in the Tibetan language.

Gartse Jigme assesses present injustices and the outbreak of protests across Tibet since March 2008 in the light of the brutal history of the occupation, making connections between young protestors today and religious and secular leaders over the past 50 years. He writes: “As a Tibetan, I will never give up the struggle for the rights of my people. As a religious person, I will never criticize the leader of my religion. As a writer, I am committed to the power of truth and actuality. This is the pledge I make to my fellow Tibetans with my own life.”

Gartse Jigme is known as an influential member of the monastic community and on June 18, 2012, spoke at an official conference in Rebkong (Chinese: Tongren) attended by editors from private magazines and newsletters. According to Tibetan sources in exile, during the conference, Gartse Jigme spoke of his concerns for the decrease in numbers of monasteries in the region, the moral decline among some people, and the need for government officials to “fully investigate and understand” the importance of Tibetan monastic life. He also said that government officials should not threaten people’s daily lives in the region in an arbitrary exercise of power, and that there should be an end to the conspiratorial accusations leveled by the authorities against Tibetan religion and practitioners, that have a detrimental impact on Tibetan religious culture.

DRUKLO (Pen Name: Shokjang)

Tibetan (Wylie): ‘Brug lo, Zhogs ljang

Druklo (pen name: Shokjang) an intellectual, blogger and writer, is known for his reflective and thought-provoking articles on issues of contemporary concern such as ethnic policy and settlement of nomads. There was widespread dismay when he was detained by security police in Rebkong (Chinese: Tongren) on March 19 (2015).

Tashi Rabten (Theurang), another well-known young generation writer, was detained with Druklo on an earlier occasion, in 2010, and wrote a moving piece called ‘Remembering a Friend on a Special Day’, translated by High Peaks Pure Earth.[48] He writes: “Today is April 6, 2015, and exactly five years ago, we were arrested and thrown behind bars by Chinese police. This day remains an unforgettable day in my life, because I reflect on and revisit the experience time and again. Contrary to the circumstances, it is neither a sense of animosity and outrage nor a feeling of regret and loss that keeps this memory alive. Today is the day I was criminalised for being a Tibetan even though I have never accepted myself as a criminal and considered the date a dark day in my life. But it is an unforgettable day for reasons my words fail to demonstrate.

“I remember today from five years ago, I remember the very day, vividly. I remember my long hair sheared off my head. I remember my proud and spirited friend. Shokjang is always animated and enthusiastic. He is someone who never deters from expressing his views, and whose courage and aspiration for freedom is unwavering. He devotes his time and intellect in the fight against darkness and oppression. When a mind or voice like his is stifled and silenced for a time or forever, it is the unpropitious cloud of darkness and oppression that ushers a reign of terror in the land.”

Shokjang was a rare voice among Chinese intellectuals on the issue of ethnic policy; he wrote a densely-argued response to a piece by Chinese liberal scholar Liu Junning, who had posted an article “Rethinking the Policy of Regional Ethnic Autonomy in Light of the Kunming Incident”. In his response, Shokjang wrote: “Tibetans do not wish or aspire to create conflict and violence among nationalities in China; they solely aspire for an autonomous Tibetan nationality within China. I would hazard that the same applies to Uyghurs too. So, the strategy of annihilating the rights of nationalities is a seriously harmful and a thoughtless scheme. On the contrary, with the current model of autonomous nationalities as a basis, if a federal system of autonomous administration of provinces based on the principles of liberty and equality is established, which I think is feasible, internal conflicts between ethnic groups would simply subside and disappear.”[49]

Shokjang also translated another article by Liu Junning into Tibetan. Many of Tibet’s young generation of intellectuals and writers are equally comfortable writing in Chinese and Tibetan, and often their concerns mirror those of their Chinese counterparts.

TSULTRIM GYALTSEN (Shogdril)

A respected writer in his late twenties from Driru, Tsultrim Gyaltsen, also known as Shogdril, was sentenced to 13 years in prison according to Tibetan sources.[50]

A respected writer in his late twenties from Driru, Tsultrim Gyaltsen, also known as Shogdril, was sentenced to 13 years in prison according to Tibetan sources.[50]

27-year old Tibetan writer Tsultrim Gyaltsen was taken from his home by police in the middle of the night on October 11, 2013, in Driru. Tibetans in two villages and a local middle school staged a hunger strike following the detention, according to Tibetan exile sources in contact with Tibetans in the area. Fifteen Tibetans were detained after calling for Tsultrim Gyaltsen’s release, according to Radio Free Asia.[51]

The next day, Tsultrim Gyaltsen’s friend Yugyal was detained, with local officials claiming that he had spread rumors that cause problems for ‘regional social stability’, according to the same sources. Yugyal has subsequently been sentenced to ten years.[52]

Tsultrim Gyaltsen, a former monk, is a young Tibetan writer who was educated in local primary school, and then studied in various monasteries in Kham and Amdo, including Kirti in Ngaba (Chinese: Aba), Shechen and Dzogchen monasteries in Derge county, in Kardze Prefecture. He is known for his lively and perceptive essays and poetry, written in both Tibetan and Chinese. In 2007, he published two books, ‘Chimes of Melancholic Snow’ and the ‘Fate of Snow Mountain’. In 2009, Tsultrim Gyaltsen disrobed and joined the Northwest University for Nationalities in Lanzhou, Gansu province, where he studied Chinese language and writing. In 2012, together with fellow Tibetan students, he began editing an annual literary journal entitled ‘The New Generation’ and became the chief editor. He also started a blog,[53] which is currently blocked by the authorities.

According to the same Tibetan sources, just a few months from his graduation in May (2013), Tsultrim Gyaltsen was expelled from the university. TCHRD reported: “It appears that he was expelled for his opinions and writings […] Sources told TCHRD that Tsultrim Gyaltsen often used to hold debate sessions at the university with fellow students. Some of the subjects debated at this informal sessions were deemed ‘illegal’ by the authorities.”

One of Shogdril’s poems, ‘Ugly Lhasa’, is a poignant reflection on contemporary Lhasa and was translated into English by TCHRD: “I visited every nook and corner of Lhasa/Apart from bars and brothels spread throughout the alleys/Apart from beggars and wanderers on busy streets/Apart from the believers and civilians of Barkhor Street/Apart from tourists in the deserted temples/Apart from frightening situations/Apart from sad tragedies/I haven’t found any beauty/Any place where it is possible/To work in peace and contentment.”[54]

THAMKEY GYATSO

Thamkey Gyatso prior to his detention.  Thamkey Gyatso in court following his arrest; the still is from official media footage. |

Labrang monk Thamkey Gyatso is serving a 15-year sentence following his involvement in political protests in 2008. Thamkey Gyatso, who is severely ill in prison, was also respected for his writings, which before his imprisonment were published in many local newspapers and month magazines.

A Tibetan familiar with his writing said: “He was a well known young Tibetan writer, and most of his pieces concerned the well-being of the Tibetan people and the failed policies of the Chinese government. His writing was rich in detail and content and he is very respected, with a strong sense of Tibetan identity.”

Thamkey Gyatso, who is in his early thirties, was arrested on April 29, 2008 in Labrang, following the major protests in March, 2008.[55] In one of the longest sentences imposed on Labrang monks said to be involved in the peaceful protest, he was sentenced to 15 years.

There are serious concerns for Thamkey Gyatso’s health, as he was believed to be severely tortured upon detention. Although he was known to be in good health before his detention, according to a Tibetan source, the right side of Thamkey’s body is now paralyzed and he can no longer walk. “His right eye, ear, hand and leg are no longer functional,” said the source. “He has received some medical treatment but nothing that has helped him to recover. He is unable to move and he just sits on a wheelchair. He can still speak slowly and recognize people.”

KUNCHOK TSEPHEL

Tibetan (Wylie): Dkon mchog tshe ‘phel

Chinese: Gongjue Cibai or Gongque Caipei

Kunchok Tsephel, an official in a Chinese government environmental department and founder of the influential Tibetan literary website, Chodme ‘Butter-Lamp’, www.tibetcm.com), is serving 15 years in prison on charges of disclosing state secrets, according to reports from Tibet received by Tibetan exiles. Some of the charges are believed to relate to content on his website, which aims to protect Tibetan culture, and possibly to passing on information about protests that took place in Tibet in 2008.

Thirty-nine year old Kunchok Tsephel was detained in the early hours of the morning on February 26, 2009. His house was ransacked and his computer, camera and mobile phone seized. His family had no idea where he was until November according to the same sources. They were summoned to court on November 12, 2009, to hear the verdict of 15 years imprisonment after a closed-door trial at the Intermediate People’s Court in Kanlho (Chinese: Gannan) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Gansu province.

Kunchok Tsephel, who was born into a nomadic family in 1970 in Machu (Chinese: Maqu) county, Kanlho (Chinese: Gannan), the eastern Tibetan area of Amdo, is fluent in Tibetan, English and Chinese. He studied English and Chinese languages at Beijing Nationality University, and from 1997-99 continued to study English at Northwest Nationalities University in Lanzhou. In 2004, he was recruited as a Tibetan and English language teacher at the Tibetan Nationality Middle School in Machu, in addition to his work for the Chinese government environmental department. He founded his website on Tibetan arts and literature in 2005, together with a young Tibetan poet Kyabchen Dedrol. The website, which was shut down by the authorities several times over the past few years, was self-funded with a mission of promoting Tibetan arts and literature.[56]

KHENPO KARTSE

Khenpo Kartse is a respected abbot (Khenpo), educator and intellectual serving a two and a half year sentence following his detention in December, 2013.

Khenpo Kartse is a respected abbot (Khenpo), educator and intellectual serving a two and a half year sentence following his detention in December, 2013.

Khenpo Kartse’s detention caused widespread distress, with hundreds of Tibetans gathering peacefully to protest his arrest at a prayer ceremony, and a rare silent vigil on his behalf outside a prison last year. In a further demonstration of the strength of local feeling about the lama’s arrest, officials from his home area of Nangchen travelled to Chamdo (Chinese: Changdu) where the Khenpo is being held, to express their concerns about the innocence of Khenpo Kartse, but to no avail, according to Tibetan sources in exile in contact with people in the region.[57]

Karma Tsewang is a highly-educated and respected abbot (Khenpo) at the Gongya Monastery in Nangchen, Yulshul (Yushu) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, in Qinghai Province. A film he made about survivors of the earthquake in Kyegudo (Yushu) in 2010 was later banned from circulation by the authorities, but circulated widely underground.

Khenpo Kartse is believed to be unwell with a liver condition and has not been allowed access to the doctor who has been treating him for some time with his medical condition. His relatives have also been denied access to him.

TOPDEN

Status: Sentenced to five years in prison

Topden, a 30-year old nomad and writer who writes under the pseudonym Dro Ghang Gah, was sentenced to five years in prison on November 30 for “keeping contacts with Dalai clique and for engaging in activities to split the nation”.

Topden was detained following unrest in the Driru region in Nagchu. Tibetan sources believe that his imprisonment was to punish him for writing a poem detailing the suffering of Tibetans in Driru county since the beginning of the year.[58] The poem, a copy of which has been obtained by ICT, gives details of the crackdown including the incommunicado detention of a 69-year old layman, mining at a local sacred mountain, and the early years of Chinese rule in the late 1960s when thousands of Tibetans were starved, imprisoned and killed.

WANGDU, MIGMAR DHONDUP, and YESHE CHOEDRON

Even after seven years, there is still virtually no information about the welfare of a group of Tibetan intellectuals imprisoned in 2008 and sentenced to long prison terms, most likely in Chushur (Qushui) Prison, Lhasa, the Tibet Autonomous Region. Migmar Dhondup, a thoughtful, well-educated Tibetan passionate about Tibetan culture and nature conservation, was sentenced to 14 years in prison in 2008, while Wangdu, who worked for an international public health NGO, was sentenced to life (details below).

WANGDU

Tibetan (Wylie): Dbang ‘dus

Chinese: Wangdui

Status: Sentenced to life

Wangdu, who worked for an international public health NGO, was sentenced to life imprisonment after he allegedly shared, or attempted to share, information about the situation in Tibet. Wangdu, a former Project Officer for an HIV/AIDS program in Lhasa run by the Australian Burnet Institute, was charged with ‘espionage’ by the Lhasa City Intermediate People’s Court after he was detained on March 14, 2008, the day that demonstrations turned violent in Lhasa.

Wangdu was accused of collecting “intelligence concerning the security and interests of the state and provid[ing] it to the Dalai clique… prior to and following the ‘March 14’ incident.”[59]

Forty-one year old Wangdu is a former Jokhang monk from Dechen Township, Taktse (Chinese: Daxi) County, around 25 kilometers east of Lhasa. He previously served eight years in prison after detention on March 8, 1989, the day martial law took effect in Lhasa after three days of protest and rioting. His three-year sentence to “re-education through labor” was extended to eight years’ imprisonment after he and 10 other political prisoners signed a petition stating that the 1951 17-Point Agreement was forced on an independent Tibet. Wangdu, who speaks fluent Chinese and once worked as a guide for Chinese tourists at the Jokhang, is still listed as a member of staff on the website of the Melbourne-based Burnet Institute, one of the leading medical research and public health Institutes in Australia. Wangdu worked on the HIV Prevention in Lhasa Project, which commenced in 2001 with AusAID and Burnet Institute funding, and aimed to develop resources to be used to educate Tibetans about HIV.

A former political prisoner who shared a cell in Tibet Autonomous Region Prison (Drapchi) and carried out labor with Wangdu in the prison’s greenhouses during his previous sentence told ICT: “During that time in prison [the early 1990s] I became very close to [Wangdu] and he started learning English with me from [another prisoner]. He is such an open-minded, talented, easygoing guy and got on really well with other prisoners while he was in Drapchi. He is very good at Tibetan literature and painting and Chinese language as well. He used to worry about the new generation in Tibet because they are losing their culture and their language, and he often criticized people for not being interested in anything other than money. The last time I saw him, when we said goodbye to each other, I was very sad.”

MIGMAR DHONDUP

Tibetan (Wylie): Mig dmar don grub

Chinese: Mima Dunzhu

Migmar Dhondup, who was also arrested in connection with the March 14 protests and has been sentenced to 14 years imprisonment, is in his early thirties and also worked for an NGO doing community development work. He is originally from Tingri (Chinese: Dingri) County in Shigatse (Chinese: Xigaze) Prefecture in the Tibet Autonomous Region. Migmar Dhondup, who speaks fluent English and is very well educated, also used to work as a tour guide. Both Migmar Dhondup and Wangdu were accused of collecting “intelligence concerning the security and interests of the state and provid[ing] it to the Dalai clique… prior to and following the ‘March 14’ incident”.[60]

Dhondup is a well-educated Tibetan passionate about nature conservation, who worked for the Kunde Foundation in Tibet, an NGO committed to helping marginalized and impoverished communities. Migmar Dhondup was educated in exile and on his return to Tibet some years later, he began working as a tourist guide for, among others, an American archaelogist who has surveyed over 700 ancient pre-Buddhist archaeological sites in upper Tibet.

Migmar accompanied him on several fieldwork trips traveling for many weeks in the remote northwest. The experience of seeing ancient rock art in caves and learning about Tibet’s rich history gave Migmar great pride in his native heritage and in his people, according to friends.

According to the same Tibetan and Western friends, Migmar was always happiest out in the field – conducting health trainings in villages, planting trees, or building food gardens to enable nomads to grow vegetables throughout the year. On his trips, however, the increasing levels of poverty in southern and northwestern Tibet demoralized him. He felt that he could never do enough to help those less fortunate than himself. He also cared a great deal about the preservation of Tibetan culture and encouraged other Tibetans to remember their mother tongue and wear traditional dress. He is a great reader, with one close friend saying that he was never seen without a book in his hand. One of his favourite books is Ma Jian’s ‘Red Dust’, an account by a Chinese dissident writer of his travels through Tibet.

YESHE CHOEDRON

Tibetan (Wylie): Ye shes chos sgron

Chinese: Yixi Quzhen

Status: Sentenced – 15 years

Yeshe Choedron was arrested in March 2008, and on November 7, 2008, the Lhasa Intermediate People’s Court sentenced her to 15 years imprisonment after being convicted for “espionage” for allegedly providing “intelligence and information harmful to the security and interests of the state” to “the Dalai clique’s security department,” according to the official Lhasa Evening News.[61]

DOLMA KYAB

It is only when we understand ourselves that we then have the power to understand this land that belongs to us.”

Young Tibetan writer Dolma Kyab is due to be released in September (2015) after serving ten and a half years in prison after writing a book, ‘The Restless Himalayas’, expressing his views on Tibetan culture, the future for young Tibetans, and the environment.

Dolma Kyab, who is in his early thirties and worked as a teacher, was arrested in March 2005 and is believed to be held in Qushui high-security prison just outside Lhasa, Tibet. In a letter smuggled out of prison that reached friends in exile, Dolma Kyab said that the reason for his conviction was his unpublished book, in which he writes about Tibetan geography, history and religion. He write: “They [Chinese] think that what I wrote about nature and geography was also connected to Tibetan independence…this is the main reason of my conviction, but according to Chinese law, the book alone would not justify such a sentence. So they announced that I am guilty of the crime of espionage.”

Dolma Kyab, who is from the eastern Tibetan area of Amdo (Haibei, Qinghai) is a highly educated intellectual with a Masters degree who felt more comfortable writing in Chinese than Tibetan, and also knew Japanese, according to friends. He studied history and geography at Qinghai Normal University and graduated in 1999, doing postgraduate studies at Beijing University until 2002. The manuscript of his book, which was obtained by ICT, is mostly written by hand in neat Chinese characters. Dolma Kyab writes in philosophical terms about the concept of Tibetan identity and sovereignty, and the Tibetan people’s wish for the Dalai Lama to return to Tibet. He explores the relationship between Chinese and Tibetans, saying that the reason for the ‘political burden’ suffered by Tibetans, is the way in which the Chinese “impose their way of thinking onto Tibetans”, thus “destroying the concept the Tibetans have of themselves”. The manuscript also refers to Chinese and Tibetan friends who are dear to him – his friends say that he had strong friendships with young Chinese intellectuals as well as Tibetans.

A young Tibetan man who served a term in the same prison as Dolma Kyab, Qushui (Chushur), south-west of Lhasa, said that they met and talked in late 2007, one night in a prison cell, after the Tibetan recognised him. The Tibetan source told ICT: “He was very thin, and he could not eat much, he could only eat small Tingmo [Tibetan steamed dumplings] every day – he said that he would have stomach pains if he ate rice. Mentally he is still very strong, but his memory has become very bad, he could not remember things well. He would forget things all the time.” At Qushui Prison, which has a strict and rigorous regime, there are surveillance cameras in every cell. Just over a week after protests broke out in Lhasa on March 10, and violent rioting on March 14, armed police with anti-riot shields arrived at Qushui. The same Tibetan former prisoner said that at one point on this day, March 20, Dolma Kyab seems to have been taken away, and he did not see him again. It is not known if Dolma Kyab was transferred to another prison or is still in Qushui in a different cell-block.

Extracts from Dolma Kyab’s manuscript, The Restless Himalayas, are published in English in ICT’s report, ‘Like Gold that Fears No Fire: New Writing from Tibet’ and also by High Peaks Pure Earth.[62]

Footnotes

[1] From an article published online on November 1, 2013 in the Party journal “Quishi” (“Speaking Truth”) and translated into English thanks to “High Peaks Pure Earth”: http://highpeakspureearth.com/2013/tar-party-secretary-chen-quanguo-on-new-propaganda-and-control-of-social-media-strategy/

[2] “As a Tibetan, I learn Tibetan” refers to the widespread practice of protecting the Tibetan language by speaking and learning Tibetan. Tibetans have set up ‘pure language’ groups. http://highpeakspureearth.com/2013/tibetan-soul-by-tsewang-lhamo-and-potala-by-kadrak-trayang/

[3] “Tashi Rabten remembers detained writer Shokjang”, translated by High Peaks Pure Earth and posted on April 6 (2015). http://highpeakspureearth.com/2015/tashi-rabten-remembers-detained-writer-shokjang/

[4] Tibetan scholar Lama Jabb wrote: “Tibetan popular music, like contemporary literature, is one of the artistic means through which Tibetans imagine themselves as a nation. It is also a mode of subversive narrative that counters the master narrative of Chinese state power and its colonial conception of Tibetan history and society.” ‘Singing the Nation: Modern Tibetan Music and National Identity’ by Lama Jabb, a scholar at Oxford University, in “Revisiting Tibetan Culture and History.” Dharamsala: Amnye Machen 2012, 1-29. This paper was first published online in 5HYXHG¶ (Etudes Tibetaines, No. 21 (Oct 2011), http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/ret/pdf/ret_21_01.pdf. See also https://www.wolfson.ox.ac.uk/sites/www.wolfson.ox.ac.uk/files/Lama%20Jabb%20Publications%20.pdf

[5] Mao Zedong’s ‘Talk at the Yan’an Conference on Literature and Art’, a translation of the 1943 text with commentary, Bonnie MacDougall 1980, 57-58 Center for Chinese Studies: University of Michigan

[6] Translated into English by China Copyright and Media, edited by Rogier Creemers: https://chinacopyrightandmedia.wordpress.com/2015/05/13/army-newspaper-we-can-absolutely-not-allow-the-internet-become-a-list-territory-of-peoples-minds/?utm

[7] For analysis of the new draft law, see ICT report, ‘Alarm at repressive new laws in China on counter-terror, security and NGOs’, June 3, 2015, https://savetibet.org/alarm-at-repressive-new-laws-in-china-on-counter-terror-security-and-ngos/

[8] ICT report, October 15, 2014, https://savetibet.org/new-aggressive-counter-terrorism-campaign-expands-from-xinjiang-to-tibet-with-increased-militarization-of-the-plateau/

[9] Chen was appointed Party boss in 2011 under Hu Jintao, but his article was a commentary on a speech by China’s leader Xi Jinping, and seems to have been intended to demonstrate Chen’s allegiance to Xi.

[10] Tsering Topgyal, University of Birmingham, UK, ‘Developing the “Trans-Unit” Dynamics of Securitization, Understanding the Tibetan Self-Immolations’, unpublished paper – See more at: https://savetibet.org/the-crackdown-in-tibet-under-xi-the-march-anniversaries-and-tibetan-new-year-as-xi-jinping-marks-a-year-in-power/

[11] As Hu Jintao put it in 2008, the “conflict with the Dalai clique” (…) “is not an ethnic problem, nor a religious problem, nor a human rights problem. It is a problem either to safeguard national unification or to split the motherland.” (Xinhua, April 28 2008). In 2011, before he became supreme leader, Xi Jinping took up the baton and in a major speech made in Lhasa (which we know about courtesy of Wikileaks) said: “For our country, Tibet serves as an important national security screen. It also constitutes an important ecological security screen, a major base of strategic resources reserve and a major production area of special highland agro-produce. It is home for the preservation of a unique culture of the Chinese nation and a major international tourism destination. To do a good job in Tibet facilitates our efforts to thoroughly apply the Scientific Outlook on Development and build a moderately prosperous society in all respects. It serves the need of sustainable development, and the maintenance of ethnic unity and social stability as well as overall unity and national security of the motherland. To accelerate development and maintain stability in Tibet is the strategic decision and explicit requirement of the central government.” (Xi 2011 http://search.wikileaks.org/gifiles/?viewemailid=700365)

[12] Chen Quanguo said on March 1, 2012: “Mobile phones, internet and other measures for the management of new media need to be fully implemented to maintain the public’s interests and national security.” See: “Official urges internet watch in Tibet,” March 2, 2012, Reuters, see: www.taipeitimes.com/News/world/archives/2012/03/02/2003526819

[13] Kunga Tsayang was released on January 12, 2014.

[14] Also see ICT’s earlier report: “A ‘Raging Storm’: The Crackdown on Tibetan writers and artists after Tibet’s Spring 2008 Protests”, May, 2010, https://savetibet.org/a-raging-storm/

[15] “Us, Post 2009”: essay written for ICT publication “Like Gold that Fears no Fire: New writing from Tibet”, October, 2009, https://savetibet.org/like-gold-that-fears-no-fire-new-writing-from-tibet/

[16] The three provinces are Kham, Amdo and U-Tsang, now incorporated into the Tibet Autonomous Region and Tibetan areas of Sichuan, Qinghai, Gansu and Yunnan in the PRC.

[17] Jangbu, one of the most acclaimed Tibetan poets in exile, wrote about this feeling of exile while in one’s homeland in his prose piece, “Homeland”, cited by Lama Jabb in his essay cited above. Jangbu wrote: “Our homeland is the liberating property of a term in the dictionary of the future that may only reach us from a remote place after many years. Inside that term the river is forever ebbing away while the fish, seizing the opportunity presented by the distant flow of the river, are pursuing already formed particularities in the distance. After many years, when they meet in a foreign land they will nurture a new home by an old philosophy and will have forgotten the past intimidations, massacres and betrayals, and may speak to their children of a distant river of ancient times and a distant borrowed home of the future. Upon pondering this, those who lost their homeland may only then pay attention to their homeland. In essence, homeland is our own body and the fragmentary explanation upon which the body itself relies.”

[18] Video of the Dalai Lama speaking uploaded by the Cryptik Movement, December 18, 2014, http://cryptik.squarespace.com/home/dalai-lama-the-message.html

[19] Tibetan scholar Lama Jabb wrote: “Tibetan popular music, like contemporary literature, is one of the artistic means through which Tibetans imagine themselves as a nation. It is also a mode of subversive narrative that counters the master narrative of Chinese state power and its colonial conception of Tibetan history and society.” Referencing the lyrics of Tibetan singers, Lama Jabb draws a distinction between ‘plaintive’ songs, which “constantly remind Tibetans of past and present tragedies and call for national unity and a concerted effort to change the political status quo”, and ‘spirited songs’ which “celebrate a common cultural identity among Tibetans and express an aspiration for a shared future.” ‘Singing the Nation: Modern Tibetan Music and National Identity’ by Lama Jabb, a scholar at Oxford University, in Revisiting Tibetan Culture and History. Dharamsala: Amnye Machen 2012, 1-29. This paper was first published online in 5HYXHG¶ (Etudes Tibetaines, No. 21 (Oct 2011), http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/ret/pdf/ret_21_01.pdf See also https://www.wolfson.ox.ac.uk/sites/www.wolfson.ox.ac.uk/files/Lama%20Jabb%20Publications%20.pdf

[21] Video and translated lyrics at High Peaks Pure Earth: http://highpeakspureearth.com/2013/tibetan-soul-by-tsewang-lhamo-and-potala-by-kadrak-trayang/

[22] Protection of the Tibetan language has been a particular focus of the self-immolators in both Amdo and Kham. In one of the most harrowing videos of the aftermath of a self-immolation, a Tibetan called Ngawang Norphel is filmed lying on his side in Zilkar monastery with his disfigured face and head visible. [He self-immolated together with Tenzin Khedup on June 20, 2012, in Tridu (Chinese: Chengduo) county, Yushu Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Qinghai.] Clearly in agonizing pain, Ngawang Norphel begins to talk about his concerns, with the Tibetan language mentioned first: “My people have no freedom of language. Everybody is mixing Tibetan and Chinese. Be that as it may, take my wealth. I don’t need them. What has happened to my Land of Snow? What has happened to my Land of Snow? […][This is] for the sake of Tibet. We are in the land of snow. If we don’t have our freedom, cultural traditions and language, it would be extremely embarrassing for us. We must therefore learn them. Every nationality needs freedom, language and tradition. Without language, what would be our nationality?”

[23] See ICT report, “Praying and lighting butter-lamps for Dalai Lama ‘illegal”: new regulations in Rebkong’, April 14, 2015, https://savetibet.org/praying-and-lighting-butter-lamps-for-dalai-lama-illegal-new-regulations-in-rebkong/

[24] Translation by Lama Jabb. Three passages of this poem are on p 35, ICT report, “Like Gold that Fears no Fire: New writing from Tibet”, October, 2009, https://savetibet.org/like-gold-that-fears-no-fire-new-writing-from-tibet/

[25] See ICT report, “Torture and impunity: 29 cases of Tibetan political prisoners”, https://savetibet.org/new-report-documents-endemic-torture-in-tibet-and-climate-of-impunity/

[26] Article by Dechen Pemba, July 9, 2014, “Braving High Risks and Heavy Censorship in China, Tibetan Musicians Sing Their Love for Tibet”, http://globalvoicesonline.org/2014/07/09/braving-high-risks-and-heavy-censorship-in-china-tibetan-musicians-sing-their-love-for-tibet/

[27] ‘Tibetan rap on Chinese knuckles flusters Beijing’, by Kate Saunders, Guardian on Sunday (India), http://www.sunday-guardian.com/analysis/tibetan-rap-on-chinese-knuckles-flusters-beijing

[28] Radio Free Asia report, November 29, 2014, http://www.rfa.org/english/news/tibet/singers-11292014130459.html

[29] https://www.youtube.com/watch?t=41&v=Seh4TIQVvdI

[30] Posted on April 29, 2015, http://www.phayul.com/news/article.aspx?id=36004

[31] Radio Free Asia report, April 23, 2012, http://www.rfa.org/english/news/tibet/singer-04232012190043.html

[32] ICT report, November 20, 2014, https://savetibet.org/harsh-new-rectification-drive-in-driru-nuns-expelled-and-warning-of-destruction-of-monasteries-and-mani-walls/

[33] See the campaign by UK-based Free Tibet to free imprisoned Tibetan singers: http://freetibet.org/singers/gongpo-tsezin

[34] In February 2014, UN offices covering areas such as freedom of expression, cultural rights, arbitrary detention and minority rights under the UN High Commission for Human Rights sent a joint representation about jailed Tibetan musicians to the Chinese authorities. The Chinese authorities replied with this information about Gongpo Tenzin; see Free Tibet UN offices covering areas such as freedom of expression, cultural rights, arbitrary detention and minority rights.

[35] In 2009, Tibetans in different areas of Tibet marked the beginning of the Chinese New Year by ‘mourning’ and in somber reflection on the crackdown following the protests that swept across Tibet, according to sources in Tibet. In an unprecedented “outpouring of emotion”, many Tibetans posted blogs and comments mostly opposing any celebration of Tibetan New Year (Losar), which began that year on February 25 according to the Tibetan calendar, which is different to the Chinese lunar calendar. ICT report, January 27, 2009: https://savetibet.org/tibetans-in-mourning-as-chinese-new-year-begins/

[36] TCHRD report, August 13, 2013: http://www.tchrd.org/2013/08/tibetan-singer-secretly-sentenced-to-five-years-in-prison-amid-major-crackdown-in-rebkong/

[37] http://www.tchrd.org/2013/06/two-tibetan-singers-secretly-sentenced-but-whereabouts-unknown/

[38] https://www.https://savetibet.org/tibetan-singers-jailed-after-release-of-songs-about-self-immolation-dalai-lama/

[39] http://highpeakspureearth.com/2013/music-video-this-is-how-it-is-by-chakdor/

[40] http://www.rfa.org/english/news/tibet/praised-06132013144450.html

[41] http://freetibet.org/singers/chakdor-and-pema-tinley

[42] http://www.tchrd.org/2014/12/two-tibetan-artists-receive-harsh-sentences-severe-fines-for-creation-of-tibetan-music/

[43] http://chrdnet.com/2014/12/chrb-beijing-police-detain-outspoken-intellectuals-close-2-independent-groups-1121-124-2014/. http://freetibet.org/singers/pema-rigzin

[44] http://tibetexpress.net/news/china-releases-tibetan-singer-gepey/

[45] http://sinosphere.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/05/28/tibetan-protest-singer-is-said-to-be-under-arrest/?_r=0

[46] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2HPjTAjj24c

[47] Also see ICT report ‘A Raging Storm: The Crackdown on Tibetan writers and artists after Tibet’s Spring 2008 Protests’, https://savetibet.org/a-raging-storm/

[48] http://highpeakspureearth.com/2015/tashi-rabten-remembers-detained-writer-shokjang/ Tashi Rabten, a well-known essayist, writer and editor of banned literary magazine Eastern Snow Mountain, served four years in prison before his release in March, 2014. In a conversation circulating on social media following his release, he wrote the following: http://www.tchrd.org/2015/03/i-was-criminalized-for-expressing-my-views-writer-tashi-rabten-in-a-recent-interview-a-year-after-release-from-prison/

[49] Translation by High Peaks Pure Earth, http://highpeakspureearth.com/2014/conflict-and-resolution-a-response-to-liu-junning-by-shokjang/

[50] TCHRD report, http://www.tchrd.org/2014/04/writer-among-two-sentenced-to-harsh-prison-terms-of-10-to-13-years-in-diru-county/ and http://www.thetibetpost.com/en/news/tibet/3975-tibetan-writer-shogdril-sentenced-to-13-years-jail-term

[51] http://www.rfa.org/english/news/tibet/pushing-11082013170614.html

[52] TCHRD report, http://www.tchrd.org/2014/04/writer-among-two-sentenced-to-harsh-prison-terms-of-10-to-13-years-in-diru-county/

[53] http://xiuzheng.tibetcul.com/131613.html#253254

[54] http://www.tchrd.org/2013/10/in-defence-of-truth-detained-tibetan-writers-poem-translated/

[55] For details of the protests, see ICT report, ‘Tibet at a Turning Point: The Spring Uprising and China’s New Crackdown’, https://savetibet.org/tibet-at-a-turning-point/

[56] https://savetibet.org/founder-of-tibetan-cultural-website-sentenced-to-15-years-in-closed-door-trial-in-freedom-of-expression-case/; and www.internationalpen.org.uk/index.cfm?objectid=264A6A72-3048-676E-26881BFF062C1C43.

[57] ICT report, https://savetibet.org/popular-religious-teacher-khenpo-kartse-sentenced/

[58] https://savetibet.org/new-images-of-deepening-crackdown-in-nagchu-tibet/

[59] ICT report, https://savetibet.org/ngo-worker-sentenced-to-life-imprisonment-harsh-sentences-signal-harder-line-on-blocking-news-from-tibet/

[60] A translation of the official news report is at: https://savetibet.org/ngo-worker-sentenced-to-life-imprisonment-harsh-sentences-signal-harder-line-on-blocking-news-from-tibet/

[61] ICT report, https://savetibet.org/ngo-worker-sentenced-to-life-imprisonment-harsh-sentences-signal-harder-line-on-blocking-news-from-tibet/

[62] http://highpeakspureearth.com/2014/on-unity-third-chapter-of-the-restless-himalayas-by-dolma-kyab/