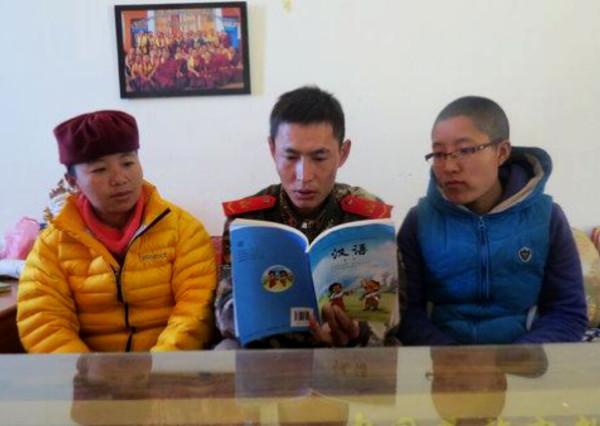

An image from the state media showing a Public Security Border Defense Corps Detachment officer in Shigatse, Tibet Autonomous Region, talking to Tibetan Buddhist nuns about ‘scientific knowledge and cultural education’, according to the article.

New systematic and long-term security measures are being rolled out in the eastern Tibetan areas of Kham and Amdo as part of an intensified control agenda set at the highest levels in Beijing and in line with a ‘counter-terror’ campaign.

“It has gone beyond a simple ‘crackdown’ now, and is much more sophisticated, and terrifying,” a Tibetan source told ICT after speaking to a number of Tibetans from different parts of Tibet. “Security is invisible and everywhere. It is no longer only armed police patrolling the streets; often we don’t know who the police are as they blend into society, and officials are in our homes, asking about every part of our lives.”

This report documents new and intrusive systems of security being imposed in Tibetan areas of the provinces of Qinghai, Sichuan and Gansu.[1] While rigorous and oppressive measures including an increase in Communist Party personnel at ‘grass roots’ levels have been in place since the 2008 protests in the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR), these measures to eliminate dissent and enforce compliance to Chinese Communist Party policies are now being increasingly observed in the eastern Tibetan areas of Kham and Amdo.

This dramatic expansion of the powers of military and police – backed by grass roots propaganda work and electronic surveillance – comes under the general rubric of ‘stability work’ as emphasized by China’s President and Party Secretary Xi Jinping. A meeting of the Chinese Politburo on July 30 last year presided over by Xi asserted the continued “anti-separatist” hardline approach by the authorities in Tibet, with Xinhua stating that “safeguarding national unity and enhancing ethnic unity” should be emphasized in order to achieve “long-term stability”.[2]

With a more overt military presence across the plateau and consistently hostile official stance against the Dalai Lama – now openly compared by Chinese officials to dictators and terrorists[3] – local authorities have greater scope in enforcing oppressive measures. In this political climate, almost any expression of Tibetan identity or culture not directly sanctioned by the state, no matter how moderate, can be characterized by the authorities as “creating instability” or “splittist” and therefore “criminal.” Definitions of what constitutes “criminal” activity are deliberately opaque, giving leeway for lower-level officials and security personnel to apply severe penalties.[4]

In two recent and dramatic examples of this trend, Tibetan shopkeepers in Draggo, Kardze, were ordered by a county-level ‘Comprehensive Culture Enforcement Squad’ to hand in all pictures of the Dalai Lama.[5] And in Dzoege, Ngaba, Sichuan, in December, black balaclava-clad special forces raided internet cafes and Tibetan tea shops.

The new measures are linked to a more systematic approach by the Chinese authorities aimed at controlling and managing the process of the Dalai Lama’s next reincarnation, in order to ensure the dominance of the Party state. An important function of the CCP’s powerful ‘United Front Work Department’ is seeking to ensure the co-option of Tibetan lamas in serving the Party’s political objectives. Official media reports have confirmed that the CCP authorities view the matter of the Dalai Lama’s reincarnation as “an important issue concerning sovereignty and national security.” (Xinhua, July 19, 2015).[6]

Matteo Mecacci, President of the International Campaign for Tibet, said: “The Chinese authorities have moved from instilling an oppressive environment in monasteries, nunneries and lay society in Tibet to a totalitarian one – an approach in which the state recognizes no limits to its authority, imposes a climate of fear, and seeks to regulate every aspect of public and private life. The Orwellian measures documented in this report of enhancing coercive capability and grass roots control are alarming in their implications not only for Tibet’s future but also in terms of understanding the CCP’s priorities. International governments must expose and counter China’s narrative about its governance of Tibet – these measures demonstrate a breath-taking absence of any genuine rule of law or bid for genuine stability.”

Referencing official documents obtained from Tibet, state media reports, provincial and prefectural websites, and interviews with Tibetans, this report documents the following:

- The intrusive presence of Party cadres in villages and monasteries in areas of eastern Tibet, following the ambitious deployment of a major village surveillance scheme since 2011 in the Tibet Autonomous Region.

- The establishment of village police posts and placement of officials in monasteries in the Tibetan areas of Kham and Amdo.

- The extension of a scheme of household security from the TAR to eastern Tibetan areas with a political agenda of ensuring Party dominance and control.

- More expansive grassroots measures are accompanied by overt displays of military force, sending a message that is magnified by prominent coverage in the state media. This includes ‘counter-terror’ drills in areas where peaceful protests and self-immolations have occurred, despite the absence of any violent insurgency in Tibet.

- A high number of central Party delegations visiting Tibetan areas in 2015-6 in order to emphasize Xi Jinping’s focus on ‘stability’ including visits to monasteries as well as the lay community, with the underlying message that religion is a cause of ‘instability’ that has to be ‘managed’ by the Party state.

- More systematic measures to prevent information from inside Tibet reaching the outside world in the context of heightened sensitivity over the Tibetan New Year (Losar) period (from February 9) and in the buildup to the March 10 anniversary of the Tibetan Uprising in 1959.In what has become an annual process of sealing off Tibet from the outside world, the Tibet Autonomous Region will be closed to tourists from February 26 until March 30, with all foreigners being instructed to leave by February 25.[7]

The visible and the invisible: armed raids and ideological attacks

Stills captured from the video on official TV of special forces raiding internet cafes and Tibetan tea shops in Dzoege (Chinese: Ruo’ergai), Ngaba, the Tibetan area of Amdo.

- Stills captured from the video on official TV of special forces raiding internet cafes and Tibetan tea shops in Dzoege (Chinese: Ru’ergai), Ngaba, the Tibetan area of Amdo.

- Stills captured from the video on official TV of special forces raiding internet cafes and Tibetan tea shops in Dzoege (Chinese: Ru’ergai), Ngaba, the Tibetan area of Amdo.

- Stills captured from the video on official TV of special forces raiding internet cafes and Tibetan tea shops in Dzoege (Chinese: Ru’ergai), Ngaba, the Tibetan area of Amdo.

On December 16 (2015), Qinghai TV broadcast footage of armed raids by heavily armed special forces on internet cafes and Tibetan hotels in Dzoege (Chinese: Ruo’ergai), Ngaba (Chinese: Aba) in Sichuan.[8] Paramilitary forces – clad in black balaclavas resembling the garb of terrorists elsewhere – are depicted bursting into rooms where Tibetans sit quietly at computer screens, and are shown making arrests. While the raid was not a new tactic, it sent a clear message by focusing on an internet café, representing official attempts to block and control information flow, and small private tea shops where Tibetans gather. It was notable that the footage was shown as part of an official news item in Tibetan language, sending a clear and unambiguous message to a Tibetan audience.

The voiceover stated that it was a “special operation” involving 50 armed police officers and 70 ‘inspection officers’, and carried out in the interests of “social security”.[9]

The front page of state media Aba (Tibetan: Ngaba) Daily, on January 25, 2016, showed the Sichuan Armed Police Corps engaging in combat exercises on the plateau. The newspaper said the exercises were to “improve the combat capability of forces under difficult conditions for the successful completion of the fight against terrorism”.

The Dzoege raids and counter-terror drills are the more visible elements of the Chinese authorities’ stated commitment to ensuring the Party state’s control and dominance at a grass roots level across Tibet, based on an emphasis on ‘social stability’.

As in the TAR, the security responses to protests in Tibetan areas administered by Sichuan, Qinghai and Gansu involve police raids, enforcing ‘disappearances’, torture, imprisonment and an intensified paramilitary presence at religious festivals or other occasions.[12]

After 2008, ‘stability maintenance’ in the TAR has effectively been carried out on a war footing, underpinned by a political context in which support for the Dalai Lama or expressions of religious identity are cast as obstacles to the CCP’s elaborate objectives of controlling and re-shaping the Tibetan plateau for its own purposes.[13] The authorities adopted a strategy of actively establishing Party presence in rural areas as the answer to ‘instability’. This led to a more pervasive and systematic approach to ‘patriotic education’ and a dramatic increase in work teams and Party cadres in rural areas of Tibet. While the Party frames these measures as if officials are doing no more than engaging in cozy chat with villagers, the underlying aim is to replace loyalty to the Dalai Lama among Tibetans with allegiance to the Chinese Party-state, and in doing so, to undermine Tibetan national identity at its roots.

With the aim of achieving ‘long-term political stability’, the Party authorities began to dramatically expand the number of cadres in the TAR.[14] In 2012, it was announced in the state media that the TAR authorities had selected more than 20,000 cadres and established 5,451 work teams to stay permanently in neighborhood committees in the TAR, as well as more than 13,000 cadres in more than 1500 work teams who would permanently stay in TAR prefectures and counties.[15]

This has been accompanied by a focus on encouraging Tibetans across the plateau, particularly in rural areas and a younger generation, to join the CCP in order to further ensure the allegiance of Tibetans to the Party state.[16]

Until now the longer-term and more insidious control measures of ‘stability maintenance’ have not been consistently observed in these eastern Tibetan areas. These methods are less visible and more difficult to monitor comprehensively, but they are far-reaching in their impact on Tibetan lives and implications to the survival of Tibetan religion and culture.

Systematic control measures spread from TAR

Troops moving through the streets of Rebkong (Chinese: Tongren) in Qinghai in July 2015. Major troop movements, including tanks or heavy artillery in convoys of more than 200 vehicles, were observed in different parts of Tibet in the buildup to the September 2015 anniversary of the establishment of the Tibet Autonomous Region.

The measures, documented by ICT throughout 2015, include stationing Party cadres in villages across Tibetan areas of Qinghai, Sichuan, and Gansu. An important function of the deployment of cadres is to combine ‘propaganda work’ with ‘social stability’, and to “close the gap between the Party and the masses”.[17] The reality of the campaign is an intensification of surveillance and scrutiny of Tibetans’ everyday lives, to a stifling degree.

A Tibetan researcher in exile who spoke to a number of Tibetans from different parts of Sichuan and Qinghai in December (2015)[18] told ICT: “The number one concern they shared about their lives in Tibet was around ‘invisible’ security that is being imposed with gathering force. I was told that people are terrified that the future of Kham and Amdo will be the same as the TAR [where restrictions have been more rigorous and systematic since 2008]. People from outside cannot see it and even people inside are not able to comprehend the sheer scope of it. You can no longer say, this is the police and this is not. If anything [like a self-immolation] happens, then the crackdown will be immediate, we know that. But it is the measures like the cadres in the villages that are more sophisticated and dangerous; people are in our homes, asking about everything, and knowing everything.”

An internal official document from a Tibetan area of Gansu obtained by ICT underlines the nature of the approach to grass roots security work. In a memo marked ‘confidential’ from the CCP Party Committee Rural Work Office of Gansu Province, the following instructions are given to cadres: “establish a ‘two-way contact’ mode by printing and issuing a ‘People’s Heart-Contact Card’ for cadres to contact the village and contact the household, one card per household, and which enables the masses to contact the cadres. Cadres going into villages and entering homes must clarify the means of contact at their place of contact, so that when they are not in the village they can be in regular communication with the masses, thereby establishing a two-way contact method and system which is quick and convenient for both parties.”

A questionnaire for cadres to distribute among villagers includes the questions: “Which services would you most like to see provided in the area of spiritual culture? What plans do you yourself have for escaping poverty and attaining prosperity? What demands do you have of the cadres’ way of thinking and work style? What is your greatest expectation of the Party and government?”[19]

Instructions for Party cadres featured in the state media included the following: “Carry out ‘three explains and three brings’ activities based on explaining policies, explaining ideology and explaining the law, and bringing science and technology, bringing information and bringing warmth. Carry out focused propaganda in the contact village no less than twice a year, and have a chat and exchange with the contact household no less than twice a year.”[20]

In an indication of the scale and importance of this approach, in Qinghai, the authorities reported that since Party cadres had been deployed in this way since 2011, the province had spent 4.6 billion yuan ($699,715,568) on ‘grass roots Party organisation’, with another report referring to tens of thousands of Party cadres deployed for grass roots work in the villages of Qinghai.[21]

The full extent of the deployment of cadres and officials in Tibetan areas of these provinces is difficult to ascertain, as only select figures are released in the state media. One official report stated that on December 26 (2015), 7865 cadres were selected for village-based work teams in Qinghai, including 3000 cadres posted from different Tibetan areas.[22]

In a further indication of the high political priority of the new measures, the state media reported that in 2014, more than 9079 Party offices had been built in villages and townships across Qinghai.[23]

There has been an emphasis too on taking the ‘stability maintenance’ message to villages in the Tibetan language and local dialects. In Dzoege, Sichuan (the Tibetan area of Amdo) – where the police raid was carried out on internet cafes at the end of last year – police teams were sent on horseback to remote villages to carry out door to door ‘legal education’. A state media report stated: “The People’s Security Bureau selected multiple language speakers” (likely to refer to Tibetan and Chinese) in order to publicize Party policies among villagers.”[24]

In Golog (Chinese: Guoluo) Tibet Autonomous Prefecture in Qinghai, the official media reported that a Tibetan language course for cadres had been set up in May, 2015, with officials participating in ‘bilingual courses’. This was as part of a broader effort to ensure that cadres can communicate official policy at a grass roots level.[25] Regional and local officials know that using ‘stability maintenance’ (Chinese: weiwen) terminology can be a means of obtaining increased resources from the central authorities.

Party cadres in Tibetan areas of Qinghai, Sichuan and Gansu: ‘an efficient set of batteries’

There appears to be a particular emphasis on grass roots control mechanisms in restive areas of Qinghai, Sichuan and Gansu where there have been protests, self-immolations or other expressions of Tibetan national identity.

Security measures have been particularly oppressive for instance in Ngaba (Chinese: Aba), Sichuan (the Tibetan area of Amdo), linked to its political and historical importance. Ngaba, which was the first Tibetan area to be subject to oppression from the Red Army during the Long March in 1935, is where the wave of Tibetan self-immolations began in 2009 when a monk from the important monastery of Kirti, Tapey, set himself on fire after the cancellation of a religious ceremony.[26]

According to the official Aba Daily, grass roots Party members are “just like an efficient set of batteries; it is necessary to recharge them frequently, and then they can be used to light up people in the dark.” The same report in the state media in November 2015 stated that more than 1800 Party cadres were deployed in 606 villages across the prefecture.[27]

Kardze is also an area where Tibetans have been active in peaceful political protest, with monks, nuns, and laypeople taking to the streets in 2008 and 2011 in bold demonstrations calling for freedom, the release of local and respected religious teachers, and for the Dalai Lama to return home – despite the certain knowledge of violent reprisals and imprisonment.[28] Kardze, one of 18 counties in Kardze (Chinese: Ganzi) prefecture in Sichuan, has been the site of more known political detentions of Tibetans by Chinese authorities than any other county outside the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) since the current period of Tibetan political activism began in 1987.[29]

In 2008, the prefectural daily newspaper had observed that the county’s remote location and “historical reasons” – a reference to Tibetan pro-independence sentiment and loyalty to the Dalai Lama – had made the work of “maintaining public order and safeguarding stability…very arduous.”[30]

Official media reported that in 2015, more than 1360 officials from Party and government offices had been selected to work at village-level in Kardze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, evidence that the authorities are seeking to limit space for such gatherings still further.[31]

Consistent with these measures in politically sensitive areas such as Kardze, local authorities are taking more extreme steps to crack down on expressions of loyalty to the Dalai Lama.

As Tibetan New Year (Losar) approached this year, shop-keepers in Draggo (Chinese: Luhuo) county in Kardze were ordered by authorities to hand over all photos of the Dalai Lama, with ‘severe punishment’ threatened for those who failed to comply by February 2 (2016).[32] Two senior monks were also detained following a prayer ceremony for the Dalai Lama’s long life and health in Kardze last month.[33]

While photographs of the Dalai Lama are rarely on display in the TAR, in recent years they have still been visible in parts of Kham and Amdo. This new ruling, issued on January 4 by the “County Comprehensive Culture Enforcement Squad” in Draggo, was endorsed later in the official media, raising the possibility of similar orders in other areas. Referring to the ban in Kardze, the state newspaper the Global Times cited Lian Xiangmin, of the China Tibetology Research Centre in Beijing, as saying that for Chinese people, hanging his picture was the same as displaying Saddam Hussein’s image would be for Americans.[34]

‘Meetings become silent when we mention the Dalai Lama’

In another politically sensitive area, Kanlho (Chinese: Gannan) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, in Gansu, the official press announced in September (2015) the deployment of ‘thousands’ of cadres to “build a strong grass roots team”. The prefecture set up a total of 405 village-based work teams including more than 1532 selected party cadres, according to the report from the Gansu government website.[35]

There have been a number of self-immolations by Tibetans in Kanlho, most recently by Tashi Kyi, a Tibetan mother of four in her mid-fifties who set herself on fire on August 27, 2015, and died, apparently as a protest against China’s policies of relocation and demolition of housing.[36]

Another state media report on Kanlho from January 21 (2016) stated that Party cadres visited a total of 112,100 people in different villages in the prefecture, including provincial and county-level officials. The figures were given according to the level of the cadres – the highest level cadres from the province visited 45 people, for instance, while cadres at county-level visited 18,851 people. The same article acknowledges that cadres are accommodated in the homes of local families in order to carry out their official duties, and that the ‘grass roots Party administration’ in Kanlho had invested more than 2 billion yuan (US$ 304131640.00) in the scheme.[37]

The same Tibetan researcher said: “The Party tells people it is all about poverty alleviation and there is no doubt that there is a strong focus on improving prosperity. But for most people, they feel the effect on their lives in a very different way, in a way that is intrusive and threatening to the very survival of their values, culture and religion.”

According to a state media report cited by Human Rights Watch, Party cadres in village are required to carry out the so-called ‘five duties’, of which three are political or security operations; building up Party and other organizations in the villages, ‘maintaining social stability’, and carrying out ‘Feeling the Party’s kindness’ education with villagers.[38]

In a rare interview, a former work team member gave an insight into the way grass roots cadres operate in the TAR, telling a Tibetan in exile:[39] “Villagers don’t mind too much when we read our or teach them the Party’s policy and how kind the Party is, because we have many programs, including singing, games, and competitions. But even so, when we ask them questions about Dalai, they always hesitate and seem uncertain about answering. When it comes to the stage of opposing the Dalai, most villagers find it very difficult and the meetings often become silent at this point. They even do not want to look at us. Yes indeed, interestingly there are few villagers who would oppose Dalai publicly at a village meeting. All the documents that we are given by the government, which are meant to be read and distributed, are about ‘good party policy’ and ‘bad Dalai clique’.”

‘Stability maintenance’ in China and Tibet is increasingly regarded as a flawed tool of CCP control that is not only ineffective in dealing with underlying social problems, but also counter-productive. It is “a national policy that has overridden all boundaries and rules”, according to civil rights lawyer Pu Zhiqiang, who has since been given a three year suspended jail sentence in December (2015).[40]

Chinese scholar Xie Yu, who studied grass roots security measures including the deployment of Party cadres in villages across the PRC, said in a research paper: “Over the past decade, the CCP has greatly increased its investment in public security within grassroots communities. However, the empirical analysis demonstrates that this additional central government expenditure has not performed as expected. […] The social and political stability in these areas has remained as fragile as before or has become even worse. In other words, the financial reform in public security has failed to produce the expected outcome.”[41]

Village-level police stations and official presence in monasteries

As part of the new grass roots, longer-term ‘management’ of ‘stability’ outside the TAR, the Chinese authorities are also establishing police stations at village-level.

In just one prefecture in Gansu, Kanlho (Gannan), according to official figures, 589 local police administrative offices were set up, and more than 1080 security personnel installed 1700 close-circuit television cameras in the main streets of townships.[42] In Qinghai, the state media announced that more than 5793 police under 50 were being sent to grass roots public security bureau in order to ‘improve policing” at this level.[43]

In a disturbing indicator of the process by which police were chosen to administer these offices, local Tibetan graduates in a county in Qinghai found that the government was hiring via a random ballot, without taking into account education background. The Tibetan graduates who had applied for village police jobs in Tsekhog (Chinese: Zeku) county in Malho Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture (the Amdo region of Tibet), wrote a petition in response that circulated on social media, saying, “We, college graduates are truly shocked. Is Tsekhog county unique? Does this mean that all parents in Tsekhog County need not send their children to school? Is education useless?”[44]

Another profound concern for Tibetans is the installation of Party officials in monasteries, even in remote areas. In one prominent reference to this in Qinghai, the official newspaper the Global Times reported that the county government of Nangchen (Chinese: Nangqian), stated that it would choose 13 people from local governments and other public institutions to be stationed in the monasteries as “part of the province’s program to assist monks’ welfare and educate them on the negative influence of separatist ideas.”[45]

Lian Xiangmin, an expert at the China Tibetology Research Center, was cited in the same article as saying “Most of the monks are law-abiding, but some of them may be used by hostile foreign forces and religious extremists such as the Dalai Lama and could cause damage to both the monasteries and society.”

Management of monasteries for ‘security’ purposes

The Party Secretary of Kardze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Hu Changsheng, is pictured in the official media visiting Larung Gar monastery on February 5, 2015. Management of monasteries by Party officials has been stepped up in line with the new ‘stability drive’ in Kham and Amdo.

The CCP responded to the protests across Tibet in 2008 by intensifying an established anti-Dalai Lama campaign, issuing sweeping regulatory measures that intrude upon Tibetan Buddhist monastic affairs and implementing aggressive “legal education” programs that pressure monks and nuns to study and accept expanded government control over their religion, monasteries, and nunneries.

The measures used to implement state religious policy have been particularly harsh in Tibet because of the close link between religion and Tibetan identity. Issues relating to religion are perceived as being essential to the eradication of ‘separatism’, a factor underpinning China’s strategic aims and development plans in Tibetan areas of the PRC.

The heavy security in Tibetan monasteries, often accompanying political ‘patriotic education’ campaigns, has been a strong source of concern among Tibetans for some time. According to unofficial sources, for instance, Tibetans made bold appeals for an end to troop deployment in monasteries to the annual session of the regional Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference held in Xining, Qinghai province in January, 2014.

Troops with riot shields gathering at Kumbum for the Monlam prayer festival, which began on February 10, 2014.

The establishment of police stations in monasteries in Tibetan areas is part of the rollout of this process. While police stations in major monasteries of the TAR were established many years prior to 2008, the drive has been accelerated since then and state media indicates a more recent focus on policing monasteries in various areas of Kham and Amdo.[46]

Throughout 2015, a number of official delegations travelled to different monasteries in Tibetan areas to emphasize the importance of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s ‘stability’ message[47] and to underline the importance of the CCP’s management of monasteries.

The ‘stability’ drive is also linked to more expansive measures aimed at controlling and managing the process of the Dalai Lama’s next incarnation, accompanied by efforts by the CCP’s powerful ‘United Front Work Department’ in seeking to ensure the co-option of Tibetan lamas in serving the Party’s political objectives.

In 2015, the Chinese authorities constricted space for Tibetan Buddhist culture still further and sought to give a higher profile to Gyaltsen Norbu, installed by the Beijing leadership as the Panchen Lama. The Panchen Lama recognized by the Dalai Lama, Gendun Choekyi Nyima, was ‘disappeared’ at the age of five in 1995.[48]

Last month, the state media reported that of all the 600 members of the TAR Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), the country’s top national advisory body, more than 100 are religious figures (Xinhua, January 28, 2016). Xinhua stated: “They […] guided Buddhist followers to see through the 14th Dalai clique’s splittist schemes, effectively maintain religious harmony and promote Tibetan Buddhism to adapt to the socialist society.”

After the 2008 protests, Tibetan language, culture and monasteries have been depicted by many Party officials as a source of ‘instability’. Just prior to Chinese New Year in 2015, the Party Secretary of Kardze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture visited the well-known Larung Gar religious institute in Serthar (Chinese: Seda), Sichuan, with the state media reporting that it had been the ninth official visit in a year. This underlined the political importance to the authorities of asserting control over one of the most significant centers of Tibetan Buddhist practice on the plateau.[49]

These official visits are intended to complement grass roots ‘stability’ efforts in the monasteries, with government websites detailing the number of Party officials sent to specific monasteries, particularly in restive areas. The website of the Kanlho (Gannan) prefectural authorities in Gansu stated that around 9674 Party officials have publicized CCP imperatives on stability to “more than 10,000 Tibetan Buddhist monks and nuns” in 2014, and that more than 1700 teachers at the monasteries in Kanlho were trained by the Party authorities.[50]

In Qinghai, the head of the United Front Work Department of the province visited a number of monasteries in 2015, observing “more than a thousand Party officials” at work in villages and monasteries.[51] The senior official, Tenkho emphasized that the management of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries was strongly connected to ‘overall social stability’.[52]

In some areas, Party officials have cracked down on what they characterize as ‘illegal fundraising’ – which refers to monks accepting offerings for prayers, a traditional practice in Tibetan communities. As part of this effort, in April 2015, the local authorities in Joni county in Kanlho (Chinese: Gannan) in Gansu, organized a public educational session on “maintaining financial stability, a harmonious society, and combating illegal fundraising”.[53]

Connected to this is a more aggressive and formalized response by the Chinese authorities to the wave of self-immolations in Tibet since 2009, in which monks have been imprisoned even for offering prayers. Two monks in Qinghai, Tsundue and Gedun Tsultrim, became the first to be imprisoned for attempting to say prayers for a Tibetan who set fire to himself. They were arrested on November 21, 2012, as they were on their way to pay their respects and say prayers at the home of Wangchen Norbu, a 25-year old Tibetan man who had died after self-immolating two days earlier near Kangtsa Gaden Choepheling monastery in the Kangtsa area of Qinghai.[54]

In some areas, the state media has publicized details of fire drills involving monks being trained to use fire extinguishers – apparently linked to the high number of Tibetan self-immolations that have taken place at monasteries or near religious sites.

Chinese writer Wang Lixiong, who is married to the prominent blogger, author and poet Tsering Woeser, has observed: “Laws and police power are actually less effective than religion in creating social stability, because they only act as a negative deterrent and operate through the principle of punishment. […] It is a mistake to treat religion as the enemy. China is making such a mistake.”[55]

Monks in a Tibetan area of Qinghai, Malho, depicted in the state media receiving fire extinguishers as part of a new drive connected to self-immolations that have taken place in Tibetan monasteries.

Security grid ‘double-linked household’ scheme extended outside TAR

The official policy known as ‘double-linked household’ scheme was first imposed in the TAR as a tool for surveillance and income generation among groups of households. The system, which was well-established in the TAR in 2013, is known as ‘double-linked’ because it refers to “households linked for security and also for increased income”. A state media article referred to the scheme involving schools and monasteries as well as homes in the TAR in 2013.[56] The system has now been extended to areas outside the TAR.

The policy fits within the “grid” management system (Tibetan: dra ba, Chinese: wangge), which was initially introduced into urban parts of the TAR in April 2012 and described by the authorities as aimed at improving public access to basic services. In a report about the system, Human Rights Watch stated: “The system also significantly increases surveillance and monitoring, particularly of ‘special groups’ in the region – former prisoners and those who have returned from the exile community in India, among others.”[57]

Outside the TAR, the objective of the ‘double-linked household’ scheme appears to be based more on economic development although security priorities are still embedded in the policy approach.

In Ngaba (Chinese: Aba) prefecture, the state media announced implementation of the ‘double-linked households’ scheme in order to “deepen the direct connection between the Party cadres and the people” and alleviate poverty from the end of 2014 onwards.[58] The cadres in Ngaba should: “Tightly and resolutely fight for three major objectives ‘development, people’s livelihood and stability’”, according to the same state media article.

The confidential Party document referred to above and dated 2012 details plans for the system in Gansu province, stating that the ‘link’ in this case is between cadres and villages with the ostensible aim of poverty reduction. It states: “All work units in all areas must scientifically and rationally formulate a ‘Link to the Villages Link to the Households, Enrich the People for the sake of the People’ implementation plan […] and building a well-off society in an all-round way and the work plans in the Provincial Committee and Government’s overall work deployments, and by integrating the actual conditions in the linked villages and households, and in accordance with local conditions.”[59]

By July last year the scheme was clearly more advanced in Gansu, with an official report in Kanlho (Gannan) referring to a pilot of 120 ‘double-linked households’ participating in bilingual courses (Tibetan and Chinese) for village-based ‘Tibetan and Chinese’ cadres.[60] The state media also reported that the scheme would be expanded in Kanlho Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture and extended to monasteries and nunneries as part of the “ground-breaking maintenance of stability work” in the region.[61]

The new ‘counter-terror’ context

The context of the new security measures is a political environment in which there is a deeper emphasis by the CCP on countering ‘terrorism’, which is conflated with ‘religious extremism’ as defined by the Party state however it chooses.

ICT monitored a number of counter-terror drills across Tibet in 2015, for example on February 7, 2015, in Xining, when special forces worked with railway police, the Public Security Bureau and other departments.[62]

China passed its first counter-terror law on December 27 (2015), rejecting concerns from international governments that draconian measures in the name of national security are being used to crack down on Tibetans, Uyghurs and Chinese civil society and to undermine religious freedom. The ‘counter-terror’ drive in Tibet and Xinjiang has involved extra-judicial killings, torture and imprisonment, and crackdowns on even mild expressions of religious identity and culture.[63]

Matteo Mecacci, President of the International Campaign for Tibet, said: ”The sweeping measures introduced in the new law are not only about countering terrorism, but about silencing criticism of the CCP and in particular its ethnic policies. Peace and stability cannot be achieved through hyper-securitization and suppression of human rights – nor by a political campaign against a globally-renowned Nobel Peace Prize laureate, the Dalai Lama, whose influence has been critical in ensuring that Tibetans do not turn to violence as an answer to oppression.”

FOOTNOTES

[1] Tibet was traditionally comprised of three main areas: Amdo (northeastern Tibet), Kham (eastern Tibet) and U-Tsang (central and western Tibet). The Tibet Autonomous Region was set up by the Chinese government in 1965 and covers the area of Tibet west of the Drichu or Yangtze River, including part of Kham. The rest of Amdo and Kham have been incorporated into Chinese provinces, and where Tibetan communities were said to have ‘compact inhabitancy’ in these provinces they were designated Tibetan autonomous prefectures and counties. As a result most of Qinghai and parts of Gansu, Sichuan and Yunnan provinces are acknowledged by the Chinese government to be ‘Tibetan.’ ICT uses the term ‘Tibet’ to refer to all Tibetan areas currently under the jurisdiction of the People’s Republic of China.

[2] ICT report, ‘Major troop movements in Tibet; hardline approach to Dalai Lama in key policy talks’, August 12, 2015, https://www.https://savetibet.org/major-troop-movements-in-tibet-hardline-approach-to-dalai-lama-in-key-policy-talks/

[3] A recent state media article (Global Times) likened the Dalai Lama to Saddam Hussein, following an earlier accusation by a senior Chinese official Zhu Weiqun that he supported ISIS. The state media article now appears to have been taken offline. See ICT report, December 22, 2015, https://savetibet.org/communist-party-official-known-for-virulent-attacks-on-dalai-lama-comes-under-unprecedented-criticism/

[4] See ICT report, ‘The Teeth of the Storm’, June 14, 2015: https://savetibet.org/the-teeth-of-the-storm-lack-of-freedom-of-expression-and-cultural-resilience-in-tibet/

[5] ICT report, February 11, 2016, https://savetibet.org/dalai-lama-compared-to-iraqi-dictator-by-chinese-state-media-as-order-issued-for-seizure-of-pictures/

[6] A state media article stated: “The title ‘Dalai Lama’ itself, which can be loosely rendered as ‘ocean of wisdom’, was officially conferred on the 5th Dalai Lama by the central Chinese government in 1653. Since then, all confirmations of the Dalai Lama have required approval by the central Chinese government, which has deemed the process an important issue concerning sovereignty and national security.” Xinhua online: http://www.china.org.cn/china/Off_the_Wire/2015-07/19/content_36095684.htm. This issue will be investigated further in a forthcoming ICT report.

[7] http://www.tripadvisor.co.uk/ShowTopic-g294222-i6446-k9209471-Tibet_is_closure_is_from_25th_Feb_to_30th_Mar_2016-Tibet.html

[8] Dzoege is in Ngaba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture, the Tibetan area of Amdo. The footage was broadcast on December 16, 2015, at http://www.qhtb.cn/qhtv/qhxw/2015/12-16/31669.html

[9] ICT translation of the Tibetan voiceover of the broadcast.

[10] More than 140 Tibetans have set themselves on fire since 2009, most calling for freedom and the return of the Dalai Lama to Tibet: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=3463&

[11] Aba Daily, January 25, 2016 (http://www.abadaily.com/html/2016-01/25/content_17804.htm). The article stated that even though temperatures on the plateau had dropped to minus 10 degrees, the Armed Police Corps were training in arrest and tactics in order to cultivate a ‘fighting spirit’.

[12] Images have emerged from Tibet over the past few years of intimidating troop deployment at significant religious festivals in eastern Tibet, particularly at the time of Tibetan New Year and in the March anniversary period. See ICT report, https://savetibet.org/the-crackdown-in-tibet-under-xi-the-march-anniversaries-and-tibetan-new-year-as-xi-jinping-marks-a-year-in-power/

[13] The state media declared in February 2012 that the situation in Tibet is so grave that officials must ready themselves for “a war against secessionist sabotage.” Tibet Daily, February 10, 2012.

[14] For further details on this campaign, see ‘China: No End to Tibet Surveillance Program, Human Rights Watch report, January 18, 2015, https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/01/18/china-no-end-tibet-surveillance-program and ICT report, ‘Storm in the Grasslands: Tibetan self-immolations and Chinese policy’, p 47 https://savetibet.org/storm-in-the-grasslands-self-immolations-in-tibet-and-chinese-policy/

[15] Tibet Daily, March 11, 2012. Xizang TV news had reported on July 18, 2009, that the training of a new generation of Party members at a grass roots level was essential. The same source also stated that by 2010, at least one ‘well-trained’ Party member for 150 citizens would be deployed in order to contribute information about “potential threats to maintaining social security in the region”.

[16] Various figures on Communist Party membership are given by state media for different areas. Tibetans in rural areas and a younger generation are particularly targeted. For instance the State Organisation Department of Kardze (Chinese: Ganzi) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture reported on July 6, 2015 that there were around 28513 Party members, with the total population of those from a farming and nomadic background reaching 36,787.

[17] Translation of information from the state media by ICT, April 15, 2015, outlining the plans for sending Party cadres to village areas in Malho (Chinese: Huangnan) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Qinghai http://www.qhaudit.gov.cn/info/1010/7783.htm

[18] Details of their identity withheld due to the dangers for Tibetans in speaking about such matters, whether in exile or inside Tibet. The Tibetans who gave their views were speaking on condition of anonymity and included monks, laypeople, young Tibetans from a nomadic background. They were speaking to the researcher in December, 2015.

[19] The document, translated into English by ICT, is headed: ‘Gansu Province Electronic Communication’ and has the seal of the CCP Gansu Province Party Committee Rural Work Office. The rest of the header reads: ‘Confidential – Special Seal for Electronic Communications/Electronic communication work unit: CCP Gansu Province Party Committee Link to Villages Link to Households Enrich the People for the People Action Coordinating and Promoting Leading Small Group’.

[20] Published on Baidu in Chinese, and translated into English by ICT: http://baike.baidu.com/subview/8923657/8905203.htm

[21] In Qinghai, the provincial authorities announced that since 2011, spending on ‘grass roots Party organisation and innovative social management’, including the placing of cadres at village-level, was allocated 4.6 billion yuan ($699242274.00). In the TAR, 25% of the regional authority’s budget was spent on stationing Party cadres in villages. (State media report, March 8, 2012, http://news.ifeng.com/mainland/special/2012lianghui/daiyanlu/detail_2012_03/08/13061544_0.shtml, cited by Human Rights Watch, in its report on January 18, 2016, https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/01/18/china-no-end-tibet-surveillance-program)

[22] State media report at http://www.chinanews.com/df/2015/12-26/7689089.shtml, December 26, 2015. Also see report from September 6, 2015, in Chinese, http://epaper.tibet3.com/qhrb/html/2015-06/09/content_251021.htm

[23] China Daily, August 26, 2014.

[24] Sichuan Daily, January 7, 2015, http://www.scga.gov.cn/jwzx/mtbd/201501/t20150108_10174.html

[25] Xining Evening News, June 8, 2015, http://www.qh.gov.cn/zwgk/system/2015/06/08/010166674.shtml

[26] Kirti Rinpoche, the head of Kirti monastery in Ngaba who lives in exile in Dharamsala, India, speaks about the ‘wounds of three generations’ in Ngaba. In a testimony to the U.S. Congress, he said: “Apart from the general suffering of the people of Ngaba Autonomous Prefecture, the people of this region have a particular wound causing excessive suffering that spans three generations. This wound is very difficult to forget or to heal.” His testimony, made on November 3, 2011, is at: https://savetibet.org/testimony-of-kirti-rinpoche-chief-abbot-of-kirti-monastery-to-the-tom-lantos-human-rights-commission/

[27] http://www.zzdjw.com/n/2014/1128/c373724-26114316.html

[28] See ICT report, June 27, 2011, https://www.https://savetibet.org/dozens-of-tibetans-imprisoned-in-new-wave-of-kardze-demonstrations-protest-in-lhasa-by-dargye-monk/

[29] Based on data available in the Congressional-Executive Commission on China (CECC) Political Prisoner Database. ‘Party, Government Launch New Security Program, Patriotic Education, in Tibetan Area’, May 5, 2008, Congressional-Executive Commission on China report, http://www.cecc.gov/publications/commission-analysis/party-government-launch-new-security-program-patriotic-education-in

Also see ICT report, June 27, 2011, https://www.https://savetibet.org/dozens-of-tibetans-imprisoned-in-new-wave-of-kardze-demonstrations-protest-in-lhasa-by-dargye-monk/

[30] Ganzi Daily, January 4, 2008.

[31] Report issued January 19, 2016, http://www.kbcmw.com/html/xw/dzyw/19044.html On February 8 (2016) information emerged that two senior monks had been detained after more than a thousand Tibetans gathered to pray for the Dalai Lama’s health on January 25 in Kardze. Tibetan Center for Human Rights and Democracy report, http://www.tchrd.org/abbot-and-senior-monk-detained-for-holding-prayer-for-dalai-lamas-health/

[32] ICT report, February 11, 2016, https://savetibet.org/dalai-lama-compared-to-iraqi-dictator-by-chinese-state-media-as-order-issued-for-seizure-of-pictures/

[33] Ibid and ICT report, January 25, 2016, https://www.https://savetibet.org/news-of-dalai-lamas-medical-treatment-prompts-long-life-prayers-in-tibet/

[34] Global Times, February 3, 2016.

[35] September 29, 2015, http://www.gn.gansu.gov.cn/html/2015/gnyw_0929/3115.html

[36] ICT report, ‘Self-immolation of ‘generous Buddhist devoted to her family’ in Tibet’, September 4, 2015, https://savetibet.org/self-immolation-of-generous-buddhist-devoted-to-her-family-in-tibet/

[37] Xinhua report, January 21, 2016, http://www.gs.xinhuanet.com/dfwq/gannan/2016-01/21/c_1117846292.htm

[38] The other two duties involve promoting economic development and providing practical benefit to the villagers. ‘China: No End to Tibet Surveillance Program, Human Rights Watch report, January 18, 2015, https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/01/18/china-no-end-tibet-surveillance-program. The report cites Wang Jieyi, “The Cadres-stationed-in-villages work must be done thoroughly and properly,” (གྲོང་ཚོར་བཅའ་སྡོད་ལས་དོན་གཏིང་ཟབ་དང་ཏན་ཏིག་སྒོ་ནས་སྤེལ་དགོས། Grong tshor bca’ sdod las don gting zab dang tan tig sgo nas sbel dgos), China Tibet News net, August 8, 2015, http://tb.xzxw.com/xw/xwpl/201508/t20150814_753705.html. For interviews with work team members about the work they do, see ICT report, ‘Storm in the Grasslands: Self-immolations in Tibet and Chinese policy’, https://savetibet.org/storm-in-the-grasslands-self-immolations-in-tibet-and-chinese-policy/

[39] Identities of both are withheld. The interview took place when the work team member was on a visit outside Tibet.

[40] Cited by Reuters, April 20, 2012, ‘China security chief down but not out after blind dissident’s escape,’ www.reuters.com/article/2012/04/30/us-china-politics-security-idUSBRE83T06J20120430

[41] Xie Yue, ‘Rising Central Spending on Public Security and the Dilemma Facing Grassroots Officials in China’, in: Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, 42, 2, 79–109, February 2013.

[42] Published on Kanlho Tibet Autonomous Prefecture official website at http://118.182.78.87:8000/gntitbetn/qtpagedata/articaldisp.asp?threeid=2&id=880

[43] Qinghai Tibetan Language Broadcasting, October 8, 2015, http://ti.tibet3.com/news/tibet/qh/2015-10/08/content_545020.htm.

[44] A copy of the petition can be viewed at: https://www.https://savetibet.org/newsroom/tibet-tidbits/

[45] ‘Tibetan monks in Qinghai to be educated on separatism’, Global Times (in English) by Kou Jie, November 26, 2015.

[46] ICT reported a rare comment by an anonymous Tibetan who had just been recruited to work in a police station in a Tibetan area. While the authenticity of the message could not be fully verified, the anonymous netizen said that the work was ‘unfamiliar’, and they were unsure of how to deal with it. The netizen said that they were uncomfortable by the conflicting requirements of improving the relationship with the monastery, respecting the monastic tradition, and at the same time watching what the monks are saying and doing. ICT report, June 20, 2014, https://savetibet.org/escalation-of-surveillance-over-monks-as-authorities-announce-opening-of-police-stations-in-tibetan-monasteries/

[47] See ICT reporting on the important Sixth Tibet Work Forum, September 8, 2015, https://www.https://savetibet.org/tough-warnings-on-anti-separatism-from-party-leaders-at-political-anniversary-in-tibet/

[48] This issue will be investigated further in the next ‘Inside Tibet’ report.

[49] Chinese state media report, February 9, 2015, http://paper.kbcmw.com/html/2015-02/09/content_68632.htm

[50] Uploaded on the Kanlho Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture website at http://118.182.78.87:8000/gntitbetn/qtpagedata/articaldisp.asp?threeid=2&id=880

[51] Qinghai state media, February 25, 2015, http://www.qhtb.cn/news/china/2015/02-25/17039.html

[52] Report on a visit to different areas of Qinghai on December 8-9, 2014, Qinghai state media, December 12, 2014, http://www.fjnet.com/jjdt/jjdtnr/201412/t20141216_225914.htm

[53] Official website, Gannan, Gansu, April 23, 2015, http://www.gannancn.cn/html/2015/znx_0423/7894.html

[54] ICT report, June 6, 2013, https://savetibet.org/two-monks-imprisoned-for-three-years-after-prayers-for-a-tibetan-self-immolator/

[55] Wang Lixiong, in his essay “The End of Tibetan Buddhism” in “The Struggle for Tibet,” by Wang Lixiong and Tsering Shakya, (Verso, 2009) p. 168.

[56] China news online, December 29, 2013, http://www.chinanews.com/df/2013/12-29/5675337.shtml

[57] ‘China: Alarming New Surveillance, Security in Tibet’, March 20, 2013, https://www.hrw.org/news/2013/03/20/china-alarming-new-surveillance-security-tibet

[58] Official media report, November 28, 2014, http://www.zzdjw.com/n/2014/1128/c373724-26114316.html

[59] Source as in footnote 14.

[60] Gansu government website, September 29, 2015, http://www.gn.gansu.gov.cn/html/2015/gnyw_0929/3115.html

[61] Gannan prefecture website, March 17, 2015, http://www.gannancn.cn/html/2015/gn_0317/7427.html

[62] Report in the state media, February 10, 2015, http://epaper.tibet3.com/qhfzb/html/2015-02/10/content_217864.htm

[63] ICT analysis of the new law, ‘China’s first counter-terror law and its implications for Tibet’, January 7, 2016, https://savetibet.org/chinas-first-counter-terror-law-and-its-implications-for-tibet/