DESTRUCTION, COMMERCIALIZATION, FAKE REPLICAS

UNESCO MUST PROTECT TIBETAN CULTURAL HERITAGE

DESTRUCTION, COMMERCIALIZATION, FAKE REPLICAS

UNESCO MUST PROTECT TIBETAN CULTURAL HERITAGE

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Lhasa’s unique and precious remaining cultural heritage, due to be discussed at the upcoming UNESCO meeting in Bahrain (opening June 24), is imperiled as China fails to uphold its responsibilities provided by the World Heritage Convention and UNESCO guidelines.

Since the iconic Potala Palace and other significant buildings were recognized as UNESCO World Heritage in 1994, 2000, and 2001, termed by UNESCO as the ‘Potala Palace Historic Ensemble’, dozens of historic buildings have been demolished in Tibet’s ancient capital and the cityscape transformed by rapid urbanisation and infrastructure construction in accordance with China’s strategic and economic objectives. Four months on from a major fire at the holy Jokhang Temple in the heart of the city, the Chinese government is still blocking access and information and may be covering up substantial damage with inappropriate repair work.

The UNESCO World Heritage Committee, at its upcoming session in Manama, Bahrain (June 24-July 4), is to vote on a draft decision which requests information about the state of conservation of the ‘Potala Palace Historic Ensemble’ and of its surroundings, the so- called “buffer zones”, “as soon as possible”.[1] The draft decision also requests more detailed reports about the damage at the Jokhang temple and seeks an invitation for a ‘Reactive Monitoring Mission’ to assess the damage and repair work at the temple.

Bhuchung Tsering, Vice President of the International Campaign for Tibet, said: “Lhasa – the name means ‘Place of the Gods’ – was the center of Tibetan Buddhism, a city of pilgrimage, a cosmopolitan locus of Tibetan civilization, language and culture. In a travesty of conservation, ancient buildings have been demolished and ‘reconstructed’ as fakes – characterized by China as ‘authentic replicas’ – and emblematic of the commercialization of Tibetan culture. The need for protection of Lhasa’s remaining heritage, particularly following the fire at the Jokhang Temple, is now urgent. The Tibetan people have a right to enjoyment and protection of their cultural heritage. The Chinese government is failing to uphold this right.”

“UNESCO must be vigilant in enforcing the World Heritage Convention and take serious measures for the protection of Lhasa’s remaining cultural heritage. As the United Nations body tasked with the protection of the world’s irreplaceable natural and cultural wonders, at the meeting in Bahrain the UNESCO World Heritage Committee must act in accordance with its mandate, and should seriously question the urban plans imposed by a government that has already destroyed many historic buildings. UNESCO should require the Chinese government to adopt an authentic conservation approach in order for the remaining fragments of old Lhasa to be preserved, based on a detailed plan to protect the historic Barkhor area and buildings in the ‘Potala Palace Historic Ensemble’.

“Importantly, the Committee and member states of the world’s leading heritage organisation should ensure urgent access for independent verification of the status of the unique and precious architecture of the Jokhang temple, and its statues and murals, with a view to ensuring that repair work is conducted under the supervision of accredited conservation experts.”

THIS INTERNATIONAL CAMPAIGN FOR TIBET REPORT DETAILS THE FOLLOWING

- The Chinese government claims that it is developing Lhasa as a “green and harmonious city”, but images and urban plans included with this report convey the scale of new development and destruction since the historic center gained World Heritage status from 1994 onwards. Chinese officials say that “maintaining social stability”, a political term meaning the repression of any form of dissent, is a precondition for Lhasa’s development.

- Images included with this report show the massive expansion and transformation of Lhasa, including infrastructure projects with roads intended to be wide enough to serve as runways for military planes in line with the Chinese government’s focus on security and militarization, dramatic expansion of the new town near Lhasa’s main railway station and high rise development in the lower Toelung valley area.

- Dozens of historic buildings were demolished in the 10 years before the Jokhang Temple was listed under UNESCO in 2000, many of them with UNESCO World Heritage status. The ancient circumambulation route known as the Lingkor, which takes pilgrims around a number of holy sites in Lhasa, has been disrupted by often impassable new roads and Chinese buildings.

- After a major fire at the Jokhang Temple, the sacred heart of Lhasa, in February, China continues to suppress information about the extent of the damage and block Tibetans from circulating news. Active engagement or promotion of heritage issues by Tibetans in Lhasa today can be dangerous, given the political climate of total surveillance and hyper-securitization, in which peaceful expression of views about Tibetan culture, identity or religion can be criminalized. No foreign journalists or heritage experts have been allowed to visit Lhasa to ascertain the situation although the Chinese authorities acknowledged to UNESCO, a month after the event, that damage to the Jokhang is extensive.

- In a response to UNESCO late last year on the ‘Potala Palace Historic Ensemble’ in Lhasa, the Chinese authorities did not mention the key issue of preservation of historic buildings. And in its submissions on Lhasa, the World Heritage Committee too does not outline specific recommendations to protect the historic Barkhor and its surroundings. Almost all of the historic buildings of old Lhasa, once the center of Tibetan Buddhism and with a pivotal role in Tibetan civilization, have been destroyed and replaced by fake ‘Tibetan’-style architecture, which is completely at odds with its UNESCO World Heritage responsibilities. Official Chinese planning documents obtained by the International Campaign for Tibet confirm that this is set to continue with the remaining historic buildings, which number around 50 as new construction continues at a staggering rate.

- The acute threat to the integrity of the UNESCO World Heritage ‘Potala Palace Historic Ensemble’ is linked to a dramatic increase in Chinese domestic tourism and a rapidly expanding infrastructure in which Lhasa is a center of a new network of roads, railways and airports with dual military and civilian use, reflecting the region’s strategic significance to the Chinese government. Official planning documents reveal that development and tourism in the interests of the ideological imperative of “harmonious socialism” are the key priorities, with conservation scarcely mentioned.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Lhasa’s unique and precious remaining cultural heritage, due to be discussed at the upcoming UNESCO meeting in Bahrain (opening June 24), is imperiled as China fails to uphold its responsibilities provided by the World Heritage Convention and UNESCO guidelines.

Since the iconic Potala Palace and other significant buildings were recognized as UNESCO World Heritage in 1994, 2000, and 2001, termed by UNESCO as the ‘Potala Palace Historic Ensemble’, dozens of historic buildings have been demolished in Tibet’s ancient capital and the cityscape transformed by rapid urbanisation and infrastructure construction in accordance with China’s strategic and economic objectives. Four months on from a major fire at the holy Jokhang Temple in the heart of the city, the Chinese government is still blocking access and information and may be covering up substantial damage with inappropriate repair work.

The UNESCO World Heritage Committee, at its upcoming session in Manama, Bahrain (June 24-July 4), is to vote on a draft decision which requests information about the state of conservation of the ‘Potala Palace Historic Ensemble’ and of its surroundings, the so- called “buffer zones”, “as soon as possible”.[1] The draft decision also requests more detailed reports about the damage at the Jokhang temple and seeks an invitation for a ‘Reactive Monitoring Mission’ to assess the damage and repair work at the temple.

Bhuchung Tsering, Vice President of the International Campaign for Tibet, said: “Lhasa – the name means ‘Place of the Gods’ – was the center of Tibetan Buddhism, a city of pilgrimage, a cosmopolitan locus of Tibetan civilization, language and culture. In a travesty of conservation, ancient buildings have been demolished and ‘reconstructed’ as fakes – characterized by China as ‘authentic replicas’ – and emblematic of the commercialization of Tibetan culture. The need for protection of Lhasa’s remaining heritage, particularly following the fire at the Jokhang Temple, is now urgent. The Tibetan people have a right to enjoyment and protection of their cultural heritage. The Chinese government is failing to uphold this right.”

“UNESCO must be vigilant in enforcing the World Heritage Convention and take serious measures for the protection of Lhasa’s remaining cultural heritage. As the United Nations body tasked with the protection of the world’s irreplaceable natural and cultural wonders, at the meeting in Bahrain the UNESCO World Heritage Committee must act in accordance with its mandate, and should seriously question the urban plans imposed by a government that has already destroyed many historic buildings. UNESCO should require the Chinese government to adopt an authentic conservation approach in order for the remaining fragments of old Lhasa to be preserved, based on a detailed plan to protect the historic Barkhor area and buildings in the ‘Potala Palace Historic Ensemble’.

“Importantly, the Committee and member states of the world’s leading heritage organisation should ensure urgent access for independent verification of the status of the unique and precious architecture of the Jokhang temple, and its statues and murals, with a view to ensuring that repair work is conducted under the supervision of accredited conservation experts.”

THIS INTERNATIONAL CAMPAIGN FOR TIBET REPORT DETAILS THE FOLLOWING

- The Chinese government claims that it is developing Lhasa as a “green and harmonious city”, but images and urban plans included with this report convey the scale of new development and destruction since the historic center gained World Heritage status from 1994 onwards. Chinese officials say that “maintaining social stability”, a political term meaning the repression of any form of dissent, is a precondition for Lhasa’s development.

- Images included with this report show the massive expansion and transformation of Lhasa, including infrastructure projects with roads intended to be wide enough to serve as runways for military planes in line with the Chinese government’s focus on security and militarization, dramatic expansion of the new town near Lhasa’s main railway station and high rise development in the lower Toelung valley area.

- Dozens of historic buildings were demolished in the 10 years before the Jokhang Temple was listed under UNESCO in 2000, many of them with UNESCO World Heritage status. The ancient circumambulation route known as the Lingkor, which takes pilgrims around a number of holy sites in Lhasa, has been disrupted by often impassable new roads and Chinese buildings.

- After a major fire at the Jokhang Temple, the sacred heart of Lhasa, in February, China continues to suppress information about the extent of the damage and block Tibetans from circulating news. Active engagement or promotion of heritage issues by Tibetans in Lhasa today can be dangerous, given the political climate of total surveillance and hyper-securitization, in which peaceful expression of views about Tibetan culture, identity or religion can be criminalized. No foreign journalists or heritage experts have been allowed to visit Lhasa to ascertain the situation although the Chinese authorities acknowledged to UNESCO, a month after the event, that damage to the Jokhang is extensive.

- In a response to UNESCO late last year on the ‘Potala Palace Historic Ensemble’ in Lhasa, the Chinese authorities did not mention the key issue of preservation of historic buildings. And in its submissions on Lhasa, the World Heritage Committee too does not outline specific recommendations to protect the historic Barkhor and its surroundings. Almost all of the historic buildings of old Lhasa, once the center of Tibetan Buddhism and with a pivotal role in Tibetan civilization, have been destroyed and replaced by fake ‘Tibetan’-style architecture, which is completely at odds with its UNESCO World Heritage responsibilities. Official Chinese planning documents obtained by the International Campaign for Tibet confirm that this is set to continue with the remaining historic buildings, which number around 50 as new construction continues at a staggering rate.

- The acute threat to the integrity of the UNESCO World Heritage ‘Potala Palace Historic Ensemble’ is linked to a dramatic increase in Chinese domestic tourism and a rapidly expanding infrastructure in which Lhasa is a center of a new network of roads, railways and airports with dual military and civilian use, reflecting the region’s strategic significance to the Chinese government. Official planning documents reveal that development and tourism in the interests of the ideological imperative of “harmonious socialism” are the key priorities, with conservation scarcely mentioned.

This image of the blaze at the holy Jokhang Temple on February 17, 2018, was captured on social media and circulated online before Tibetans were warned not to send news of the fire outside Tibet.

This image of the blaze at the holy Jokhang Temple on February 17, 2018, was captured on social media and circulated online before Tibetans were warned not to send news of the fire outside Tibet.

Newly built apartments in the west of Lhasa.

Newly built apartments in the west of Lhasa.

THE “POTALA PALACE HISTORIC ENSEMBLE”

These developments highlight the importance of an evaluation of the status of conservation in Tibet’s historic and cultural capital, Lhasa, raising urgent questions for the 42nd session of the World Heritage Committee that opens in Bahrain on June 24. The UNESCO World Heritage Committee is due to evaluate an updated report on the state of conservation of the Potala Palace, Norbulingka and Jokhang sites from the Chinese government when in Bahrain.[2] As part of this evaluation, the surroundings of the sites, the “buffer zones”, enjoy protection as well. A “buffer zone” serves to provide an additional layer of protection to a World Heritage property.[3] According to UNESCO’s Operational Guidelines, “[a]lthough buffer zones are not part of the nominated property, any modifications to or creation of buffer zones subsequent to inscription of a property on the World Heritage List should be approved by the World Heritage Committee.”[4]

The Historic Ensemble under question consists of three sites in the Lhasa valley: the Potala Palace, winter home of the Dalai Lama since the 17th century until the current Dalai Lama’s escape into exile in 1959, the Jokhang Temple, and the Norbulingka, the Dalai Lama’s traditional summer palace, including its surroundings.[5]

The three buildings were inscribed as UNESCO World Heritage in 1994, 2000, and 2001 respectively, and are described on the UNESCO World Heritage Committee website as follows: “The Potala Palace, winter palace of the Dalai Lama since the 17th century, symbolizes Tibetan Buddhism and its central role in the traditional administration of Tibet. The complex, comprising the White and Red Palaces with their ancillary buildings, is built on Red Mountain in the center of Lhasa Valley, at an altitude of 3,700m. Also founded in the 7th century, the Jokhang Temple Monastery is an exceptional Buddhist religious complex. Norbulingka, the Dalai Lama’s former summer palace, constructed in the 18th century, is a masterpiece of Tibetan art. The beauty and originality of the architecture of these three sites, their rich ornamentation and harmonious integration in a striking landscape, add to their historic and religious interest.”[6]

THE “POTALA PALACE HISTORIC ENSEMBLE”

These developments highlight the importance of an evaluation of the status of conservation in Tibet’s historic and cultural capital, Lhasa, raising urgent questions for the 42nd session of the World Heritage Committee that opens in Bahrain on June 24. The UNESCO World Heritage Committee is due to evaluate an updated report on the state of conservation of the Potala Palace, Norbulingka and Jokhang sites from the Chinese government when in Bahrain.[2] As part of this evaluation, the surroundings of the sites, the “buffer zones”, enjoy protection as well. A “buffer zone” serves to provide an additional layer of protection to a World Heritage property.[3] According to UNESCO’s Operational Guidelines, “[a]lthough buffer zones are not part of the nominated property, any modifications to or creation of buffer zones subsequent to inscription of a property on the World Heritage List should be approved by the World Heritage Committee.”[4]

The Historic Ensemble under question consists of three sites in the Lhasa valley: the Potala Palace, winter home of the Dalai Lama since the 17th century until the current Dalai Lama’s escape into exile in 1959, the Jokhang Temple, and the Norbulingka, the Dalai Lama’s traditional summer palace, including its surroundings.[5]

The three buildings were inscribed as UNESCO World Heritage in 1994, 2000, and 2001 respectively, and are described on the UNESCO World Heritage Committee website as follows: “The Potala Palace, winter palace of the Dalai Lama since the 17th century, symbolizes Tibetan Buddhism and its central role in the traditional administration of Tibet. The complex, comprising the White and Red Palaces with their ancillary buildings, is built on Red Mountain in the center of Lhasa Valley, at an altitude of 3,700m. Also founded in the 7th century, the Jokhang Temple Monastery is an exceptional Buddhist religious complex. Norbulingka, the Dalai Lama’s former summer palace, constructed in the 18th century, is a masterpiece of Tibetan art. The beauty and originality of the architecture of these three sites, their rich ornamentation and harmonious integration in a striking landscape, add to their historic and religious interest.”[6]

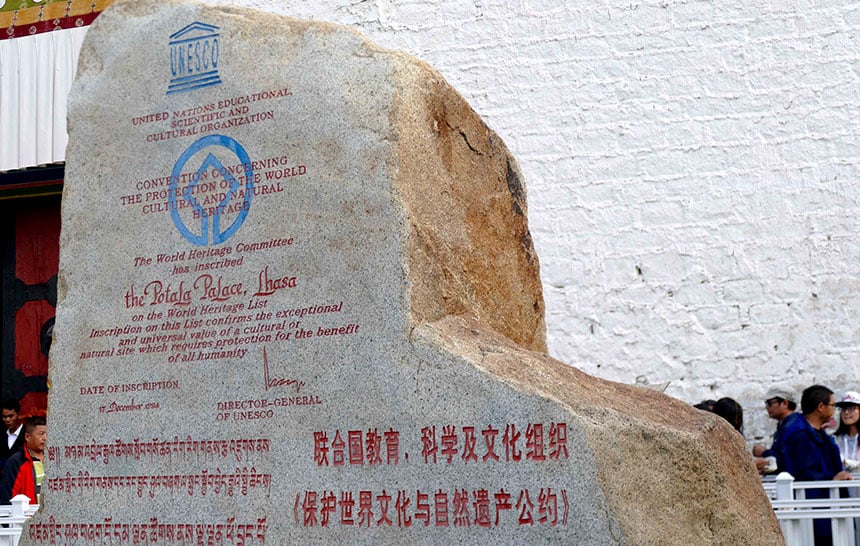

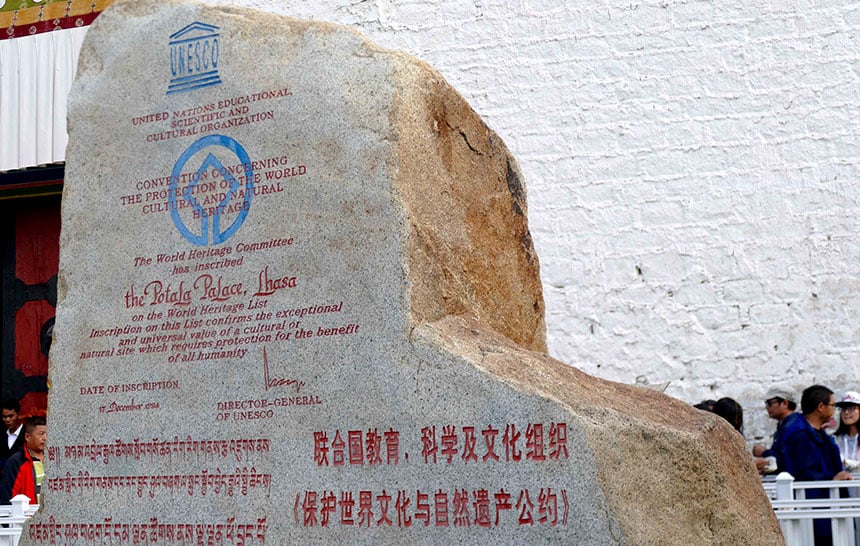

Commemorative stone marking the recognition of the Potala Palace as UNESCO World Heritage in Lhasa.

Commemorative stone marking the recognition of the Potala Palace as UNESCO World Heritage in Lhasa.

The importance of these buildings and the surrounding area to the Tibetan people or to the world cannot be overstated. The late Andre Alexander, leading scholar on Tibetan heritage and founder of the Tibet Heritage Fund,[7] wrote: “The Tibetan capital of Lhasa is more than just a city of timber and stone, glass and steel. For centuries, Lhasa’s prestige and influence as both cradle and center of Tibetan Buddhism gave it a pivotal role within Tibetan civilization.”[8] Alexander wrote about the Jokhang that it is a “miraculously-preserved physical testimony to the history of Buddhism […] The Tibetans have since long associated the Jokhang with the genesis of their cultural and religious civilization. But its importance goes even beyond that, touching the cultural histories of India, China and beyond.”[9]

It is a measure of what the Jokhang Temple means to Tibetans that after the fire on February 17 (2018), in freezing temperatures, some Tibetan pilgrims began to sleep on the ground outside the temple, demonstrating the level of distress and concern about the fate of this most sacred site, while others carried out prostrations from 4am every day.[10]

The importance of these buildings and the surrounding area to the Tibetan people or to the world cannot be overstated. The late Andre Alexander, leading scholar on Tibetan heritage and founder of the Tibet Heritage Fund,[7] wrote: “The Tibetan capital of Lhasa is more than just a city of timber and stone, glass and steel. For centuries, Lhasa’s prestige and influence as both cradle and center of Tibetan Buddhism gave it a pivotal role within Tibetan civilization.”[8] Alexander wrote about the Jokhang that it is a “miraculously-preserved physical testimony to the history of Buddhism […] The Tibetans have since long associated the Jokhang with the genesis of their cultural and religious civilization. But its importance goes even beyond that, touching the cultural histories of India, China and beyond.”[9]

It is a measure of what the Jokhang Temple means to Tibetans that after the fire on February 17 (2018), in freezing temperatures, some Tibetan pilgrims began to sleep on the ground outside the temple, demonstrating the level of distress and concern about the fate of this most sacred site, while others carried out prostrations from 4am every day.[10]

Cityscape at night, showing new developments in the foreground.

Cityscape at night, showing new developments in the foreground.

DESTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT IN LHASA

DESTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT IN LHASA

“We Tibetans love our culture, and that includes our architecture. Our homes keep us cool in the summer and warm in the winter. But now, they’re disappearing. One by one, our traditional houses seem to vanish overnight, and in their place we are given cold, concrete boxes, which we’re told are much better for us. Why? Why?”

– Unnamed Tibetan in Lhasa[11]

“We Tibetans love our culture, and that includes our architecture. Our homes keep us cool in the summer and warm in the winter. But now, they’re disappearing. One by one, our traditional houses seem to vanish overnight, and in their place we are given cold, concrete boxes, which we’re told are much better for us. Why? Why?”

– Unnamed Tibetan in Lhasa[11]

The Chinese government has repeatedly failed to preserve historic Tibetan architecture in Lhasa, despite the relatively small size of the city’s ancient core. According to the earliest existing proper survey of the city, Lhasa in 1948 consisted of around 700 traditional Tibetan town houses, a small city by any standards.[12] Today, there are around 50 left.[13]

According to documentation by Tibet Heritage Fund – which was forced to leave Lhasa in 2000 – by 1993, little more than 300 of historic Tibetan buildings remained.[14] Under the ‘Lhasa Development Plan 1980-2000’ and the ‘Barkhor Conservation Plan 1992’, most of Old Lhasa’s historic-traditional buildings were demolished and replaced with three to four story ‘neo-Tibetan’ cement houses. Many of these buildings were replaced after the Potala Palace Ensemble was nominated for UNESCO World Heritage status and the historic old town had been approved by the Chinese authorities as a ”National Historically and Culturally Famous City” with listed historic buildings in the vicinity of the Jokhang Temple designated as “Priority Protected Sites”.[15]

Notably, in 1994 efforts by the head of the UNESCO delegation, Minja Yang, to mobilise the international community against the Chinese government’s destruction of historical buildings failed.[16] Just after the nomination of the Potala Palace for UNESCO status, in early 1995, two-thirds of the historic buildings comprising the historic Tibetan government district of Shol at the foot of the Palace were demolished. By January 2010, the number of historic Tibetan buildings in Lhasa had dwindled down to less than 100, and there are now around 50.[17]

The Chinese government has repeatedly failed to preserve historic Tibetan architecture in Lhasa, despite the relatively small size of the city’s ancient core. According to the earliest existing proper survey of the city, Lhasa in 1948 consisted of around 700 traditional Tibetan town houses, a small city by any standards.[12] Today, there are around 50 left.[13]

According to documentation by Tibet Heritage Fund – which was forced to leave Lhasa in 2000 – by 1993, little more than 300 of historic Tibetan buildings remained.[14] Under the ‘Lhasa Development Plan 1980-2000’ and the ‘Barkhor Conservation Plan 1992’, most of Old Lhasa’s historic-traditional buildings were demolished and replaced with three to four story ‘neo-Tibetan’ cement houses. Many of these buildings were replaced after the Potala Palace Ensemble was nominated for UNESCO World Heritage status and the historic old town had been approved by the Chinese authorities as a ”National Historically and Culturally Famous City” with listed historic buildings in the vicinity of the Jokhang Temple designated as “Priority Protected Sites”.[15]

Notably, in 1994 efforts by the head of the UNESCO delegation, Minja Yang, to mobilise the international community against the Chinese government’s destruction of historical buildings failed.[16] Just after the nomination of the Potala Palace for UNESCO status, in early 1995, two-thirds of the historic buildings comprising the historic Tibetan government district of Shol at the foot of the Palace were demolished. By January 2010, the number of historic Tibetan buildings in Lhasa had dwindled down to less than 100, and there are now around 50.[17]

ALARMING IMPLICATIONS OF CHINA’S URBAN PLANS

Despite the unique importance of Lhasa’s cultural heritage and its remaining historic buildings, a Chinese state response to UNESCO, issued in November 2017,[18] does not refer to the fundamental issue of the preservation of the remaining historic buildings on the Barkhor or the buffer zones. And in its prior submission to the Chinese state party, UNESCO does not outline its recommendations for their protection.[19]

In the document submitted to the Chinese state party by UNESCO after the World Heritage Committee meeting in Istanbul in 2016, UNESCO even noted “with satisfaction” China’s compliance in mitigating the impact of a large shopping mall partially by “renovation of the façade in traditional Tibetan architectural style” – effectively an endorsement of China’s approach to create replicas of Tibetan historical buildings rather than preserving the actual buildings.[20]

The priorities detailed for Lhasa in official Chinese documents obtained by the International Campaign for Tibet have alarming implications for the survival of Lhasa’s remaining heritage, and adopt a different tone to those submitted to UNESCO for discussion in Bahrain at the World Heritage Committee.

China’s Master Urban Plan for Lhasa is a central element of Lhasa’s urbanization as well as a tool for territorial control and blueprint for development of the city. In the urban plan revised in 2008 and obtained by the International Campaign for Tibet, development and tourism are outlined as the key priorities in Lhasa, with conservation scarcely mentioned. The main objective outlined in the plan is ideological rather than heritage-oriented, stating the intention of the creation of “a new Lhasa [to be] built under harmonious and prosperous socialism.”[21]

Tibetan official Che Dalha (Chinese: Qi Zhala), one of the leading figures involved in Lhasa’s rapid urbanisation, has made it clear that the task of “maintaining social stability […] is the precondition and guarantee for the development of Lhasa”. Maintenance of stability is political language referring to the crushing of any dissent and ensuring allegiance to the CCP authorities in order for the authorities to pursue their strategic and economic objectives on the plateau without impediment.[22]

Images included with this report show the massive expansion and transformation of Lhasa, including infrastructure projects with roads intended to be wide enough to serve as runways for military planes in line with the Chinese government’s focus on security and militarization,[23] dramatic expansion of the new town near Lhasa’s main railway station and high rise development in the lower Toelung valley area.

In the section of the urban plan about renovation of the city for tourism, there is no mention of preservation of historic buildings, even in the section about the old town of Lhasa.[24] Chapter Nine of the Urban Plan raises the “preservation of history and culture” but only in broad and general terms.

In the same document, the Historic Ensemble area is designated as one of the main areas for “improvement” in the “short-term construction plan”, raising concerns over possible demolitions to create more tourist infrastructure.

Under the urban plan, Lhasa has not only undergone demolition of its ancient heritage, but also its not so old buildings. Emily Yeh, a scholar who has charted Lhasa’s development, writes: “The demolition of recently built single-family houses in favor of uniform row houses and apartment blocks conjures the appearance of development, producing a developed urban landscape through a process of ‘creative destruction’ that fuels capital accumulation for coalitions of real estate development companies and local governments.”[25]

A further document issued by the State Council on Lhasa city planning last year (2017) is more specific on plans to demolish old buildings, stating that the authorities will: “Speed up reconstruction of dilapidated housing and of support infrastructure in shantytowns, city-centre villages and in urban and rural areas.”[26]

In an indication of ongoing construction and demolition plans in the ancient heart of Lhasa, of which little original architectural fabric remains, construction companies were invited to tender by April (2018) for implementation of an “old city transformation strategic planning project” approved by the Party Group of the Urban and Rural Planning Bureau of Lhasa.[27]

In one of its only references to protecting culture of the city, a Chinese State Council document on Lhasa’s urban planning states not that buildings must be preserved, but that the Chinese authorities must “protect the traditional style and configuration of the city, particularly in the historical urban districts”. This is a direct reference to new buildings that have been constructed in Tibetan style.[28]

“Very often the understanding of ‘conservation’ in Asia is the replacement of historic structures by new buildings, with little or no resemblance to the old ones regarding design, building techniques or materials,” wrote Pimpim de Azevedo and the late Andre Alexander of the Tibet Heritage Fund.[29] “This causes substantial loss of historic buildings.” Azevedo and Alexander cited for example the 7th century Barkhor street in Lhasa, both a pilgrimage route and important market street, has been redesigned to “fit some kitsch view of Tibet that may appeal to national and international tourists. For example, streetlights resembling prayer wheels have been installed, and the street sellers removed elsewhere. Another example of this kind of attitude [in Lhasa] is the decorative red frieze usually used only in palaces and temples. In recent years, this type of frieze was applied without discrimination to any building, including hotels, public toilets, etc.”[30]

ALARMING IMPLICATIONS OF CHINA’S URBAN PLANS

Despite the unique importance of Lhasa’s cultural heritage and its remaining historic buildings, a Chinese state response to UNESCO, issued in November 2017,[18] does not refer to the fundamental issue of the preservation of the remaining historic buildings on the Barkhor or the buffer zones. And in its prior submission to the Chinese state party, UNESCO does not outline its recommendations for their protection.[19]

In the document submitted to the Chinese state party by UNESCO after the World Heritage Committee meeting in Istanbul in 2016, UNESCO even noted “with satisfaction” China’s compliance in mitigating the impact of a large shopping mall partially by “renovation of the façade in traditional Tibetan architectural style” – effectively an endorsement of China’s approach to create replicas of Tibetan historical buildings rather than preserving the actual buildings.[20]

The priorities detailed for Lhasa in official Chinese documents obtained by the International Campaign for Tibet have alarming implications for the survival of Lhasa’s remaining heritage, and adopt a different tone to those submitted to UNESCO for discussion in Bahrain at the World Heritage Committee.

China’s Master Urban Plan for Lhasa is a central element of Lhasa’s urbanization as well as a tool for territorial control and blueprint for development of the city. In the urban plan revised in 2008 and obtained by the International Campaign for Tibet, development and tourism are outlined as the key priorities in Lhasa, with conservation scarcely mentioned. The main objective outlined in the plan is ideological rather than heritage-oriented, stating the intention of the creation of “a new Lhasa [to be] built under harmonious and prosperous socialism.”[21]

Tibetan official Che Dalha (Chinese: Qi Zhala), one of the leading figures involved in Lhasa’s rapid urbanisation, has made it clear that the task of “maintaining social stability […] is the precondition and guarantee for the development of Lhasa”. Maintenance of stability is political language referring to the crushing of any dissent and ensuring allegiance to the CCP authorities in order for the authorities to pursue their strategic and economic objectives on the plateau without impediment.[22]

Images included with this report show the massive expansion and transformation of Lhasa, including infrastructure projects with roads intended to be wide enough to serve as runways for military planes in line with the Chinese government’s focus on security and militarization,[23] dramatic expansion of the new town near Lhasa’s main railway station and high rise development in the lower Toelung valley area.

In the section of the urban plan about renovation of the city for tourism, there is no mention of preservation of historic buildings, even in the section about the old town of Lhasa.[24] Chapter Nine of the Urban Plan raises the “preservation of history and culture” but only in broad and general terms.

In the same document, the Historic Ensemble area is designated as one of the main areas for “improvement” in the “short-term construction plan”, raising concerns over possible demolitions to create more tourist infrastructure.

Under the urban plan, Lhasa has not only undergone demolition of its ancient heritage, but also its not so old buildings. Emily Yeh, a scholar who has charted Lhasa’s development, writes: “The demolition of recently built single-family houses in favor of uniform row houses and apartment blocks conjures the appearance of development, producing a developed urban landscape through a process of ‘creative destruction’ that fuels capital accumulation for coalitions of real estate development companies and local governments.”[25]

A further document issued by the State Council on Lhasa city planning last year (2017) is more specific on plans to demolish old buildings, stating that the authorities will: “Speed up reconstruction of dilapidated housing and of support infrastructure in shantytowns, city-centre villages and in urban and rural areas.”[26]

In an indication of ongoing construction and demolition plans in the ancient heart of Lhasa, of which little original architectural fabric remains, construction companies were invited to tender by April (2018) for implementation of an “old city transformation strategic planning project” approved by the Party Group of the Urban and Rural Planning Bureau of Lhasa.[27]

In one of its only references to protecting culture of the city, a Chinese State Council document on Lhasa’s urban planning states not that buildings must be preserved, but that the Chinese authorities must “protect the traditional style and configuration of the city, particularly in the historical urban districts”. This is a direct reference to new buildings that have been constructed in Tibetan style.[28]

“Very often the understanding of ‘conservation’ in Asia is the replacement of historic structures by new buildings, with little or no resemblance to the old ones regarding design, building techniques or materials,” wrote Pimpim de Azevedo and the late Andre Alexander of the Tibet Heritage Fund.[29] “This causes substantial loss of historic buildings.” Azevedo and Alexander cited for example the 7th century Barkhor street in Lhasa, both a pilgrimage route and important market street, has been redesigned to “fit some kitsch view of Tibet that may appeal to national and international tourists. For example, streetlights resembling prayer wheels have been installed, and the street sellers removed elsewhere. Another example of this kind of attitude [in Lhasa] is the decorative red frieze usually used only in palaces and temples. In recent years, this type of frieze was applied without discrimination to any building, including hotels, public toilets, etc.”[30]

This image, which was taken before the Jokhang fire in February, shows the ‘Tibetan-style’ streetlights outside the temple.

This image, which was taken before the Jokhang fire in February, shows the ‘Tibetan-style’ streetlights outside the temple.

A Tibetan motorcyclist rides around the Potala Palace.

A Tibetan motorcyclist rides around the Potala Palace.

Two Tibetan elderly women doing a pilgrimage on the Lingkor; now Tibetans have to traverse busy roads and cross bridges to follow the holy circuit.

Two Tibetan elderly women doing a pilgrimage on the Lingkor; now Tibetans have to traverse busy roads and cross bridges to follow the holy circuit.

PILGRIMAGE TO THE ‘PLACE OF THE GODS’

Lhasa, its literal meaning being ‘Place of the Gods’, has always had a deep spiritual significance, and it is the wish of Tibetans across Tibet to go on pilgrimage there. Andre Alexander wrote that the city “was seen as an embodiment of one of the primary symbols of Buddhism, the Dharmachakra,[31] situated in a blessed landscape full of auspicious signs. In relation to Tibet, Lhasa and its temple were placed in the center, pressing down the heart of a personification of the old and uncivilized pre-Buddhist Tibet.”[32]

Today, the ancient circumambulation route of the Lingkor, which takes the pilgrim around all the holy sites in Lhasa, has been disrupted by new roads and Chinese buildings, creating a “strong sense of socio-spatial disorientation” for Tibetan pilgrims.[33]

While the UNESCO World Heritage Committee also urged China to “Include provisions in the Urban Master Plan to maintain the spatial linkages and visual corridors between the component parts of the property, their historical context and wider setting, and to promote and maintain the traditional urban structure and layout of the buffer zones. This should include, but should not be limited to, regulations regarding acceptable heights, visual qualities, façades and roofs”[34] – it did not mention the protection of existing historic buildings in terms of their architecture and authenticity.

PILGRIMAGE TO THE ‘PLACE OF THE GODS’

Lhasa, its literal meaning being ‘Place of the Gods’, has always had a deep spiritual significance, and it is the wish of Tibetans across Tibet to go on pilgrimage there. Andre Alexander wrote that the city “was seen as an embodiment of one of the primary symbols of Buddhism, the Dharmachakra,[31] situated in a blessed landscape full of auspicious signs. In relation to Tibet, Lhasa and its temple were placed in the center, pressing down the heart of a personification of the old and uncivilized pre-Buddhist Tibet.”[32]

Today, the ancient circumambulation route of the Lingkor, which takes the pilgrim around all the holy sites in Lhasa, has been disrupted by new roads and Chinese buildings, creating a “strong sense of socio-spatial disorientation” for Tibetan pilgrims.[33]

While the UNESCO World Heritage Committee also urged China to “Include provisions in the Urban Master Plan to maintain the spatial linkages and visual corridors between the component parts of the property, their historical context and wider setting, and to promote and maintain the traditional urban structure and layout of the buffer zones. This should include, but should not be limited to, regulations regarding acceptable heights, visual qualities, façades and roofs”[34] – it did not mention the protection of existing historic buildings in terms of their architecture and authenticity.

THE JOKHANG FIRE AND LHASA’S CULTURAL HERITAGE

THE JOKHANG FIRE AND LHASA’S CULTURAL HERITAGE

This image of the blaze at the holy Jokhang Temple on February 17, 2018, was captured on social media and circulated online before Tibetans were warned not to send news of the fire outside of Tibet.

This image of the blaze at the holy Jokhang Temple on February 17, 2018, was captured on social media and circulated online before Tibetans were warned not to send news of the fire outside of Tibet.

On the second day of Tibetan New Year, February 17 (2018), a fire broke out in the most sacred temple of Tibet, the Jokhang in Lhasa, Tibet’s historic and cultural capital. Videos emerged showing flames shooting from the golden roof of the temple, a place of unparalleled religious importance not only to Tibetans but also to Buddhists across the globe. In the background, the sound of Tibetans weeping in distress and praying could be heard. And then, silence. China’s Party state suppressed any news about the fire and rebuffed attempts by international experts to ascertain the damage, even though the Jokhang is a UNESCO World Heritage site. In a telling admission, Tibetans posted emojis of faces with gagged mouths.

In a stark demonstration of China’s strategies to isolate and lock down Tibet, the full extent of fire damage to Tibet’s cultural and historic heart is still unknown, and there are concerns that inappropriate repair work may be undertaken on its historic structure in order to cover up the damage, according to Tibetan sources. Immediately following the fire, the International Campaign for Tibet received information indicating that damage was likely to be extensive, backed up by assessment by experts of post-fire video footage and stills.[35]

China responded to the UNESCO World Heritage Center a month after the fire, on March 16, acknowledging damage to the Jokhang as follows: “A ventilation chamber on the 2nd floor of the Back Hall of the Main Hall caught fire and approximately 50m2 of the hall burned. Emergency measures were immediately put in place, and the Golden Ceiling of the back hall was carefully dismantled to ensure that it could not be damaged in the event that the fire had caused structural problems (which was later determined not to be the case). The Statue of Sakyamuni Buddha suffered no damage, but was given a temporary protective covering as a precautionary measure; the fire only had a minor impact on the first floor, and Jokhang Temple Monastery was therefore reopened to the public the following day; damage due to the fire included partial burn damage to the ventilation chamber and its golden ceiling and to some wooden columns and beams. The gilded bronze ceiling and other decorative elements remain intact, with several components suffering minor deformation or other burn damage. Some murals, baga [sic] soil walls, and aga [sic] soil floors from the 1980s also suffered damage.”[36]

It is not known whether the response can be taken at face value given the extent to which China has sought to cover up any damage so far. Concerns are compounded by the lack of access for architecture or heritage experts, given China’s tight grip over the region; the fire happened at a time when Lhasa and the rest of the Tibet Autonomous Region were closed to foreign visitors in what has become an annual lockdown due to the sensitive political anniversary of the 1959 March 10 Uprising and 2008 protests.[37]

Recognizing the incomplete nature of the information available on the fire’s aftermath, a draft decision has been put forward for decision of the World Heritage Committee in Bahrain, stating: “Expresses its regret at the fire of February 2018, and notes the work carried out by the State Party in the immediate aftermath of the fire; […] Requests the State Party to provide to the World Heritage Centre, for review by the Advisory Bodies, more detailed reports of all the damage caused by the aforementioned fire, including images, drawings and other graphic illustrations and paying particular attention to the Golden Ceiling, as more detailed damage assessments are being carried out and restoration plans developed”.[38]

The Chinese government is also requested to invite a joint “Reactive Monitoring” mission of the World Heritage Centre, the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) and the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM) to the Jokhang, to “assess the damage caused by the fire and the proposed restoration works to be undertaken, as well as to examine other aspects of the state of conservation of the property”.

On the second day of Tibetan New Year, February 17 (2018), a fire broke out in the most sacred temple of Tibet, the Jokhang in Lhasa, Tibet’s historic and cultural capital. Videos emerged showing flames shooting from the golden roof of the temple, a place of unparalleled religious importance not only to Tibetans but also to Buddhists across the globe. In the background, the sound of Tibetans weeping in distress and praying could be heard. And then, silence. China’s Party state suppressed any news about the fire and rebuffed attempts by international experts to ascertain the damage, even though the Jokhang is a UNESCO World Heritage site. In a telling admission, Tibetans posted emojis of faces with gagged mouths.

In a stark demonstration of China’s strategies to isolate and lock down Tibet, the full extent of fire damage to Tibet’s cultural and historic heart is still unknown, and there are concerns that inappropriate repair work may be undertaken on its historic structure in order to cover up the damage, according to Tibetan sources. Immediately following the fire, the International Campaign for Tibet received information indicating that damage was likely to be extensive, backed up by assessment by experts of post-fire video footage and stills.[35]

China responded to the UNESCO World Heritage Center a month after the fire, on March 16, acknowledging damage to the Jokhang as follows: “A ventilation chamber on the 2nd floor of the Back Hall of the Main Hall caught fire and approximately 50m2 of the hall burned. Emergency measures were immediately put in place, and the Golden Ceiling of the back hall was carefully dismantled to ensure that it could not be damaged in the event that the fire had caused structural problems (which was later determined not to be the case). The Statue of Sakyamuni Buddha suffered no damage, but was given a temporary protective covering as a precautionary measure; the fire only had a minor impact on the first floor, and Jokhang Temple Monastery was therefore reopened to the public the following day; damage due to the fire included partial burn damage to the ventilation chamber and its golden ceiling and to some wooden columns and beams. The gilded bronze ceiling and other decorative elements remain intact, with several components suffering minor deformation or other burn damage. Some murals, baga [sic] soil walls, and aga [sic] soil floors from the 1980s also suffered damage.”[36]

It is not known whether the response can be taken at face value given the extent to which China has sought to cover up any damage so far. Concerns are compounded by the lack of access for architecture or heritage experts, given China’s tight grip over the region; the fire happened at a time when Lhasa and the rest of the Tibet Autonomous Region were closed to foreign visitors in what has become an annual lockdown due to the sensitive political anniversary of the 1959 March 10 Uprising and 2008 protests.[37]

Recognizing the incomplete nature of the information available on the fire’s aftermath, a draft decision has been put forward for decision of the World Heritage Committee in Bahrain, stating: “Expresses its regret at the fire of February 2018, and notes the work carried out by the State Party in the immediate aftermath of the fire; […] Requests the State Party to provide to the World Heritage Centre, for review by the Advisory Bodies, more detailed reports of all the damage caused by the aforementioned fire, including images, drawings and other graphic illustrations and paying particular attention to the Golden Ceiling, as more detailed damage assessments are being carried out and restoration plans developed”.[38]

The Chinese government is also requested to invite a joint “Reactive Monitoring” mission of the World Heritage Centre, the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) and the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM) to the Jokhang, to “assess the damage caused by the fire and the proposed restoration works to be undertaken, as well as to examine other aspects of the state of conservation of the property”.

EXCLUSION OF TIBETANS AS SUPPORT FOR CULTURE IS DEEMED ‘REACTIONARY’

UNESCO also commends China on its efforts to “integrate traditional knowledge systems” encouraging the “formal integration” of this approach in “conservation and management arrangements for the property [the Historic Ensemble].”[39] But due to the political imperatives of the Chinese government, the space for Tibetans to be involved in decision-making on their heritage is virtually non-existent, with policy imposed from the top-down.[40]

The absence of Tibetans from the planning process is revealed by the details given in the official documents of the various central and regional government and Party departments involved in the planning process, from the first urban plan for Lhasa approved by the State Council on April 13, 1983. Throughout the process, spearheaded by the most senior leaders in the Tibet Autonomous Region, the Ministry of Construction was involved – but no local people, culture or heritage experts, are listed as being involved in the process of planning the development of Lhasa and protection of its heritage.

A response from the State Council on the overall planning as Lhasa makes the political imperatives of development of the city clear when it states: “City-level planning may not be delegated down, effectively ensuring the implementation of the plan”.[41]

In the Chinese State Council response on Lhasa’s planning, the ‘Tibetanness’ of Lhasa was even further downgraded in its description of the city as having merely “ethnic characteristics”, stating: “Lhasa is the capital of the Tibet Autonomous Region and a famous national historical and cultural city and an international tourist city with snow-covered plateau characteristics and ethnic characteristics.”[42]

This is a further indication of the current policy orientation, intensified following the important 19th Party Congress in Beijing last October, towards the elimination of protections of social and cultural differences among Tibetans and other “ethnic minorities” in the PRC, reversing earlier approaches recognizing “ethnic autonomy” and strengthening policies that undermine Tibetan language, culture and religion.[43]

An official circular distributed in Lhasa in February described the protection of Tibetan culture as a “reactionary and narrow nationalistic idea”.[44] The document, which urged the public to report on those suspected of being loyal to the “evil forces” of the Dalai Lama, referred to “22 illegal activities” effectively criminalizing those who speak about issues such as environmental protection and “folk culture” by labeling them as “‘spokespersons’ of the Dalai clique and hostile foreign [non-mainland] forces.”

In this political climate, Tibetans are likely to be fearful of being involved or speaking out about heritage issues, for instance in the aftermath of the Jokhang fire.

Overseas Tibetans with family or friends in Lhasa could usually be expected to find out more information about such incidents, but in this case they could not. Even as early as the evening of February 18, a day after the fire, a Tibetan from Lhasa who now lives in France explained that they “dare not ask for news”. Scholar and Tibetan literature specialist Francoise Robin wrote in an article about the fire’s aftermath: “Since then, that friend has only been able to learn that the monks at the Jokhang were confined to the temple on the Sunday after the fire, usually a day on which they visit their families. My friend deduced from this that Jokhang monks were prevented from going out in case they reveal to their relatives the extent of the damage.”[45] This atmosphere may explain why some early reports from Lhasa on the night of the Jokhang fire denied that the blaze had affected the Jokhang at all, despite video evidence circulating online.[46]

In the same article, Francoise Robin referred to the “worrying” silence from UNESCO itself; writing: “The Jokhang has been listed with UNESCO as a World Heritage site since 2000, but, when 30 researchers in Tibetan studies and art history wrote to the director of World Heritage Center, Dr. Mechtild Rössler, asking for the organisation to intervene urgently, the reply was that their team “is following this matter closely with the ICOMOS [International Council on Monuments and Sites] experts concerned.” No other assurance or information was offered.”[47]

Restrictions on NGOs in China and Tibet make it almost impossible to have independent evaluation of conservation efforts. The Tibet Heritage Fund, which had worked on preserving and restoring historic buildings in Lhasa, was expelled from Tibet in August 2000 after years of successful work.[48] (The order came without warning, with Chinese police ordering the Fund to stop all restoration work and shut down its office within days.)

Now international NGOs, which have encountered formidable barriers to operating in Tibet for years, have faced a new wave of shutdowns and closures following Xi Jinping’s rise to power. Repressive new laws, which came into effect in 2017, burdened NGOs with new registration and reporting requirements, and gave Chinese police organs even more power to interfere with their operations.

In addition, projects in Lhasa labeled as ‘conservation’ have removed Tibetans from their cultural heritage, including from their homes, traditional sites of worship, local neighborhoods and marketplaces.[49]

EXCLUSION OF TIBETANS AS SUPPORT FOR CULTURE IS DEEMED ‘REACTIONARY’

UNESCO also commends China on its efforts to “integrate traditional knowledge systems” encouraging the “formal integration” of this approach in “conservation and management arrangements for the property [the Historic Ensemble].”[39] But due to the political imperatives of the Chinese government, the space for Tibetans to be involved in decision-making on their heritage is virtually non-existent, with policy imposed from the top-down.[40]

The absence of Tibetans from the planning process is revealed by the details given in the official documents of the various central and regional government and Party departments involved in the planning process, from the first urban plan for Lhasa approved by the State Council on April 13, 1983. Throughout the process, spearheaded by the most senior leaders in the Tibet Autonomous Region, the Ministry of Construction was involved – but no local people, culture or heritage experts, are listed as being involved in the process of planning the development of Lhasa and protection of its heritage.

A response from the State Council on the overall planning as Lhasa makes the political imperatives of development of the city clear when it states: “City-level planning may not be delegated down, effectively ensuring the implementation of the plan”.[41]

In the Chinese State Council response on Lhasa’s planning, the ‘Tibetanness’ of Lhasa was even further downgraded in its description of the city as having merely “ethnic characteristics”, stating: “Lhasa is the capital of the Tibet Autonomous Region and a famous national historical and cultural city and an international tourist city with snow-covered plateau characteristics and ethnic characteristics.”[42]

This is a further indication of the current policy orientation, intensified following the important 19th Party Congress in Beijing last October, towards the elimination of protections of social and cultural differences among Tibetans and other “ethnic minorities” in the PRC, reversing earlier approaches recognizing “ethnic autonomy” and strengthening policies that undermine Tibetan language, culture and religion.[43]

An official circular distributed in Lhasa in February described the protection of Tibetan culture as a “reactionary and narrow nationalistic idea”.[44] The document, which urged the public to report on those suspected of being loyal to the “evil forces” of the Dalai Lama, referred to “22 illegal activities” effectively criminalizing those who speak about issues such as environmental protection and “folk culture” by labeling them as “‘spokespersons’ of the Dalai clique and hostile foreign [non-mainland] forces.”

In this political climate, Tibetans are likely to be fearful of being involved or speaking out about heritage issues, for instance in the aftermath of the Jokhang fire.

Overseas Tibetans with family or friends in Lhasa could usually be expected to find out more information about such incidents, but in this case they could not. Even as early as the evening of February 18, a day after the fire, a Tibetan from Lhasa who now lives in France explained that they “dare not ask for news”. Scholar and Tibetan literature specialist Francoise Robin wrote in an article about the fire’s aftermath: “Since then, that friend has only been able to learn that the monks at the Jokhang were confined to the temple on the Sunday after the fire, usually a day on which they visit their families. My friend deduced from this that Jokhang monks were prevented from going out in case they reveal to their relatives the extent of the damage.”[45] This atmosphere may explain why some early reports from Lhasa on the night of the Jokhang fire denied that the blaze had affected the Jokhang at all, despite video evidence circulating online.[46]

In the same article, Francoise Robin referred to the “worrying” silence from UNESCO itself; writing: “The Jokhang has been listed with UNESCO as a World Heritage site since 2000, but, when 30 researchers in Tibetan studies and art history wrote to the director of World Heritage Center, Dr. Mechtild Rössler, asking for the organisation to intervene urgently, the reply was that their team “is following this matter closely with the ICOMOS [International Council on Monuments and Sites] experts concerned.” No other assurance or information was offered.”[47]

Restrictions on NGOs in China and Tibet make it almost impossible to have independent evaluation of conservation efforts. The Tibet Heritage Fund, which had worked on preserving and restoring historic buildings in Lhasa, was expelled from Tibet in August 2000 after years of successful work.[48] (The order came without warning, with Chinese police ordering the Fund to stop all restoration work and shut down its office within days.)

Now international NGOs, which have encountered formidable barriers to operating in Tibet for years, have faced a new wave of shutdowns and closures following Xi Jinping’s rise to power. Repressive new laws, which came into effect in 2017, burdened NGOs with new registration and reporting requirements, and gave Chinese police organs even more power to interfere with their operations.

In addition, projects in Lhasa labeled as ‘conservation’ have removed Tibetans from their cultural heritage, including from their homes, traditional sites of worship, local neighborhoods and marketplaces.[49]

URBANIZATION OF LHASA AIMED AT SECURITIZATION AND CONTROL

URBANIZATION OF LHASA AIMED AT SECURITIZATION AND CONTROL

Slogan on a wall in front of new construction in Lhasa reads: “Construct a Harmonious Society”.

Slogan on a wall in front of new construction in Lhasa reads: “Construct a Harmonious Society”.

New construction, Lhasa.

New construction, Lhasa.

China’s development of Lhasa is an integral part of its policies of urbanisation in Tibet, which has been predominantly rural. Urbanisation is a key mechanism designed to meet economic objectives but with the political agenda of integrating Tibetans into the PRC, undermining ‘ethnic autonomy’ and ensuring top-down control. The intensified securitization in Tibet is dependent upon urbanisation as well as settlement of Tibetan nomads, because it makes Tibetans easier to administer and control,[50] as well as creating space for Chinese incomers.

Lhasa residents have been cited as saying that they believe they are being concentrated in such a unified fashion in new apartment complexes not only to “make space for the Chinese” but also “because people gathered together like that are easier to manage.”[51]

Both urbanization and ‘municipalisation’ – in which a rural region effectively becomes a city – were core strategies of China’s ‘Western Development’ drive under the then President Jiang Zemin in 1999-2000. But they have been advanced even more rapidly under Party Secretary Xi Jinping.

Given the high political priority ascribed to compliance with top-down planning policy, the recent Chinese State Council response on Lhasa city planning emphasized that enhanced surveillance was in place, if Lhasa citizens had any doubt: “The ‘Overall Plan’ is the fundamental basis for the development, construction and management of the city of Lhasa, and all construction activities within the urban planning district must comply with the requirements of the ‘Overall Plan’. […] Strengthen mass and social supervision, and raise awareness of social respect for urban planning. All Lhasa-based work units must respect relevant laws and the ‘Overall Plan’, support the work of the Lhasa City People’s Government, strive together, and properly plan, properly build and properly manage Lhasa City.”[52]

China’s development of Lhasa is an integral part of its policies of urbanisation in Tibet, which has been predominantly rural. Urbanisation is a key mechanism designed to meet economic objectives but with the political agenda of integrating Tibetans into the PRC, undermining ‘ethnic autonomy’ and ensuring top-down control. The intensified securitization in Tibet is dependent upon urbanisation as well as settlement of Tibetan nomads, because it makes Tibetans easier to administer and control,[50] as well as creating space for Chinese incomers.

Lhasa residents have been cited as saying that they believe they are being concentrated in such a unified fashion in new apartment complexes not only to “make space for the Chinese” but also “because people gathered together like that are easier to manage.”[51]

Both urbanization and ‘municipalisation’ – in which a rural region effectively becomes a city – were core strategies of China’s ‘Western Development’ drive under the then President Jiang Zemin in 1999-2000. But they have been advanced even more rapidly under Party Secretary Xi Jinping.

Given the high political priority ascribed to compliance with top-down planning policy, the recent Chinese State Council response on Lhasa city planning emphasized that enhanced surveillance was in place, if Lhasa citizens had any doubt: “The ‘Overall Plan’ is the fundamental basis for the development, construction and management of the city of Lhasa, and all construction activities within the urban planning district must comply with the requirements of the ‘Overall Plan’. […] Strengthen mass and social supervision, and raise awareness of social respect for urban planning. All Lhasa-based work units must respect relevant laws and the ‘Overall Plan’, support the work of the Lhasa City People’s Government, strive together, and properly plan, properly build and properly manage Lhasa City.”[52]

Surveillance camera disguised as a prayer wheel in the Barkhor area.

Surveillance camera disguised as a prayer wheel in the Barkhor area.

On July 8, 2016, a Tibetan official who has been leading urbanisation and development plans was cited as saying that the Chinese government would apply for the old town of Lhasa to be awarded world cultural heritage status.[53] Tibetan official Che Dalha, a former Party chief of Lhasa who is now governor of the Tibet Autonomous Region, told Xinhua: “Lhasa has more than 4,000 years of history, and is strewn with famous historical sites. It embodies the essence of Tibetan culture.”

As per UNESCO rules, China must first include old town Lhasa in a “tentative list” that indicates nominations eligible for formal inscription in the next five to ten years.[54] But it does not appear in the list published by UNESCO World Heritage on February 28, 2017, so will not be discussed in Bahrain, and further information about its inclusion on later lists is not known.

The credibility of the comment by Che Dalha is further undermined as he is one of the leading officials responsible for rapid urbanisation and expansion of the city of Lhasa, presiding over tough and repressive securitization measures in the Tibet Autonomous Region.

A senior Chinese diplomat, Qu Jing, has been appointed as Deputy Director-General of UNESCO (the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation), suggesting that the Chinese authorities will play an even more active role in influencing the Committee in support of their broader political aims, in which cultural heritage is a low priority. Across China, historic buildings have been razed and fake historic architecture is described as ‘heritage’ or ‘conservation’.[55] Qu Jing is a former Ambassador to France and Belgium, and his appointment at UNESCO was heralded in March (2018) by the Chinese state media as an indication of China’s increasing global influence.[56]

On July 8, 2016, a Tibetan official who has been leading urbanisation and development plans was cited as saying that the Chinese government would apply for the old town of Lhasa to be awarded world cultural heritage status.[53] Tibetan official Che Dalha, a former Party chief of Lhasa who is now governor of the Tibet Autonomous Region, told Xinhua: “Lhasa has more than 4,000 years of history, and is strewn with famous historical sites. It embodies the essence of Tibetan culture.”

As per UNESCO rules, China must first include old town Lhasa in a “tentative list” that indicates nominations eligible for formal inscription in the next five to ten years.[54] But it does not appear in the list published by UNESCO World Heritage on February 28, 2017, so will not be discussed in Bahrain, and further information about its inclusion on later lists is not known.

The credibility of the comment by Che Dalha is further undermined as he is one of the leading officials responsible for rapid urbanisation and expansion of the city of Lhasa, presiding over tough and repressive securitization measures in the Tibet Autonomous Region.

A senior Chinese diplomat, Qu Jing, has been appointed as Deputy Director-General of UNESCO (the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation), suggesting that the Chinese authorities will play an even more active role in influencing the Committee in support of their broader political aims, in which cultural heritage is a low priority. Across China, historic buildings have been razed and fake historic architecture is described as ‘heritage’ or ‘conservation’.[55] Qu Jing is a former Ambassador to France and Belgium, and his appointment at UNESCO was heralded in March (2018) by the Chinese state media as an indication of China’s increasing global influence.[56]

THE UNESCO BRAND AND TOURISM IN LHASA

THE UNESCO BRAND AND TOURISM IN LHASA

“…[This is] a vast project that rewrites history and ‘wipes out’ the memory and culture of an entire people.”

– Tibetan writer Tsering Woeser, August 24, 2013[57]

“…[This is] a vast project that rewrites history and ‘wipes out’ the memory and culture of an entire people.”

– Tibetan writer Tsering Woeser, August 24, 2013[57]

Time Square, Lhasa’s latest shopping mall on Beijing Rd, near the Potala Palace. The center includes a large supermarket, cafes and stores selling Chinese and Western brands.

Time Square, Lhasa’s latest shopping mall on Beijing Rd, near the Potala Palace. The center includes a large supermarket, cafes and stores selling Chinese and Western brands.

New construction to the east of Lhasa.

New construction to the east of Lhasa.

Together with urbanisation, a joint imperative underlying Lhasa’s development plans and the downgrading of authentic cultural heritage is tourism. The UNESCO World Heritage ‘brand’ is used as part of the Chinese government’s ambitious plans to boost high-end tourism in Lhasa and beyond, part of China’s strategic and economic objectives in Tibet. This endorsement has assisted the Chinese government in its claims to authority over Tibetan culture.[58]

In an unprecedented development, mass Chinese domestic tourism across Tibet now coexists with the untrammelled powers of a security state engaged in the most widespread political crackdown in a generation. Lhasa is a particular focus and all official planning documents refer to its importance.

Tibet Autonomous Region received nearly 2.7 million domestic tourists from January to April this year, up 63.5 percent from last year, according to the Chinese state media.[59] The same report said that according to the regional tourism development committee, the region received $26.7 million of tourism revenue during the period, a year-on-year increase of 50.7 percent. The figures are certainly inflated, with visitor arrivals bolstered to meet official quotas,[60] but that does not detract from the transformative impact of the rising tourist numbers to Lhasa, and it highlights how the Chinese government is capitalizing on the increased currency of Tibet’s cultural heritage.

The Chinese authorities have sought to ‘re-brand’ Tibet as a grid of tourist itineraries. The creation of a series of ‘tour circuits’ has been backed up by massive infrastructure investment funded by Beijing, not only the railway to Lhasa and Shigatse, but also regional airports giving tourists glimpses of Tibet’s variety of landscapes, architecture, wildlife and heritage.

Lhasa is critical to China’s 2010-2020 tourism strategy, which names the two main markets as “human culture tourism” and “ecotourism”, with “boutique tourist routes” and “safari tourism” for adventurous travellers seeking wild landscapes.

At last year’s World Heritage Committee meeting in Poland, UNESCO status was given to Hoh Xil (Chinese: Kekexili), a wild landscape between Golmud in Qinghai and Lhasa, consistent with China’s objectives to increase mass tourism to Tibet’s wilderness areas. China’s official nomination proposal required UNESCO World Heritage Committee members to accept a framework that specifically labelled traditional pastoral land-use a threat, involving the criminalization of traditional productive and sustainable activities as pastoralism and gathering medicinal herbs.[61]

The ‘commodification’ or commercialization of Tibetan culture – while the authentic culture is being undermined by Chinese policies targeting Tibetan religious identity – was evident during a Tourism Expo in Lhasa, which included a ‘re-imagining’ of the deeply symbolic former home of the Dalai Lama, the Potala Palace, in the InterContinental Hotel lobby.[62] Tibetans are increasingly marginalised by the use of Chinese as the language of tourism in Tibet, providing employment for large numbers of Chinese immigrants in a labor-intensive industry.

Tibetan writer Tsering Woeser is one of the most eloquent and astute writers on the transformation of the city of Lhasa, from the Cultural Revolution – when her father was an official photographer – to today. She says: “Comparing today with the Cultural Revolution, there were no believers kneeling back then, and the temple was ruined, while today the temple offers a bustling scene where believers may freely worship. But these are only superficial differences. Religious worship is still strictly controlled. Furthermore, there is now commercialized tourism, with gawking tourists who treat Tibetans like exotic decorations and Lhasa as a theme park.”[63]

Together with urbanisation, a joint imperative underlying Lhasa’s development plans and the downgrading of authentic cultural heritage is tourism. The UNESCO World Heritage ‘brand’ is used as part of the Chinese government’s ambitious plans to boost high-end tourism in Lhasa and beyond, part of China’s strategic and economic objectives in Tibet. This endorsement has assisted the Chinese government in its claims to authority over Tibetan culture.[58]

In an unprecedented development, mass Chinese domestic tourism across Tibet now coexists with the untrammelled powers of a security state engaged in the most widespread political crackdown in a generation. Lhasa is a particular focus and all official planning documents refer to its importance.

Tibet Autonomous Region received nearly 2.7 million domestic tourists from January to April this year, up 63.5 percent from last year, according to the Chinese state media.[59] The same report said that according to the regional tourism development committee, the region received $26.7 million of tourism revenue during the period, a year-on-year increase of 50.7 percent. The figures are certainly inflated, with visitor arrivals bolstered to meet official quotas,[60] but that does not detract from the transformative impact of the rising tourist numbers to Lhasa, and it highlights how the Chinese government is capitalizing on the increased currency of Tibet’s cultural heritage.

The Chinese authorities have sought to ‘re-brand’ Tibet as a grid of tourist itineraries. The creation of a series of ‘tour circuits’ has been backed up by massive infrastructure investment funded by Beijing, not only the railway to Lhasa and Shigatse, but also regional airports giving tourists glimpses of Tibet’s variety of landscapes, architecture, wildlife and heritage.

Lhasa is critical to China’s 2010-2020 tourism strategy, which names the two main markets as “human culture tourism” and “ecotourism”, with “boutique tourist routes” and “safari tourism” for adventurous travellers seeking wild landscapes.

At last year’s World Heritage Committee meeting in Poland, UNESCO status was given to Hoh Xil (Chinese: Kekexili), a wild landscape between Golmud in Qinghai and Lhasa, consistent with China’s objectives to increase mass tourism to Tibet’s wilderness areas. China’s official nomination proposal required UNESCO World Heritage Committee members to accept a framework that specifically labelled traditional pastoral land-use a threat, involving the criminalization of traditional productive and sustainable activities as pastoralism and gathering medicinal herbs.[61]

The ‘commodification’ or commercialization of Tibetan culture – while the authentic culture is being undermined by Chinese policies targeting Tibetan religious identity – was evident during a Tourism Expo in Lhasa, which included a ‘re-imagining’ of the deeply symbolic former home of the Dalai Lama, the Potala Palace, in the InterContinental Hotel lobby.[62] Tibetans are increasingly marginalised by the use of Chinese as the language of tourism in Tibet, providing employment for large numbers of Chinese immigrants in a labor-intensive industry.

Tibetan writer Tsering Woeser is one of the most eloquent and astute writers on the transformation of the city of Lhasa, from the Cultural Revolution – when her father was an official photographer – to today. She says: “Comparing today with the Cultural Revolution, there were no believers kneeling back then, and the temple was ruined, while today the temple offers a bustling scene where believers may freely worship. But these are only superficial differences. Religious worship is still strictly controlled. Furthermore, there is now commercialized tourism, with gawking tourists who treat Tibetans like exotic decorations and Lhasa as a theme park.”[63]

New construction in the Tibetan village of Drip, that has resulted in relocations. One Tibetan reported losing all his farmland when the Princess Wencheng spectacle for Chinese tourists opened opposite the Potala Palace.

New construction in the Tibetan village of Drip, that has resulted in relocations. One Tibetan reported losing all his farmland when the Princess Wencheng spectacle for Chinese tourists opened opposite the Potala Palace.

Referring to the Chinese government’s creation of ‘fake’ Tibetan architecture such as the fake Potala Palace used for a show presenting China’s narrative on Tibet, Tsering Woeser wrote: “In fact, this is a vast project that rewrites history and ‘wipes out’ the memory and culture of an entire people. For many years, supported by power and money, these kinds of projects have been blossoming everywhere, sweeping everything away. One can predict that this commercial theatre play put on stage in a fake Potala Palace will be a must-see of future tourist groups visiting Lhasa. They can brainwash people and make money at the same time. Those that will be harmed, however, are the Tibetans who have been invaded and deprived of their history.”[64]

In 2013, more than 200 scholars in countries across the world voiced strong concern about a project to modernize the historic center of Lhasa linked to the development of tourist infrastructure. “This destruction is not simply a matter of aesthetics,” said the petition, addressed to China’s president Xi Jinping and to UNESCO director-general Irina Bukova. “It is depriving Tibetans and scholars of Tibet alike of a living connection to the Tibetan past. […] It is bringing in its wake the forced displacement of large numbers of Tibetans from their own homes, effectively diminishing the Tibetan presence in one of the most important Tibetan cultural sites.”[65]

The Central Tibetan Administration (CTA) based in India said that it was “deeply concerned” about the project’s impact, saying it is transforming Lhasa’s central Jokhang temple and the Barkhor, or Old City, around it into a “superficial tourist spot.”[66]