ACCESS DENIED

NEW US LEGISLATION, THE QUEST FOR RECIPROCITY IN EUROPE AND THE LOCKDOWN IN TIBET

ACCESS DENIED

NEW US LEGISLATION, THE QUEST FOR RECIPROCITY IN EUROPE AND THE LOCKDOWN IN TIBET

In December 2018, U.S. President Donald Trump signed into law the Reciprocal Access to Tibet Act (RATA), the first major legislation on Tibet passed by the United States Congress since the Tibetan Policy Act of 2002 (TPA), indicative of the high level of support for Tibet in the U.S. This was followed by the passing in January 2020 in the U.S. House of Representatives of the Tibetan Policy and Support Act (TPSA), which will dramatically upgrade US political and humanitarian support for Tibetans, including sanctioning Chinese officials for interfering in the Dalai Lama’s succession.

The landmark bipartisan RATA legislation represents an important step towards holding China accountable for its policies on Tibet.

There is now an increasing awareness at European Union level of the importance of reciprocity, not only with regard to trade and economic relations, but also more generally relating to access to Tibet. Accordingly, there are moves to develop legislation in Europe, similar to the one in the United States.

RATA seeks to address the difficulties in access to the isolated and oppressed region for American diplomats, NGO workers, journalists, and all citizens whom Chinese authorities prevent from traveling freely. The Act makes it possible to deny U.S. entry to Chinese officials who are involved in policies that ultimately prohibit American citizens from access to Tibet.

The International Campaign for Tibet (ICT) has documented how multiple visits of diplomatic personnel, journalists and intergovernmental organizations from across the world to Tibet have been refused or blocked in recent years, in contravention of usual diplomatic practice between countries.

Today, the developments connected to the COVID-19 pandemic on the international stage show the determination of the Chinese Communist Party state to suppress the free flow of information and to silence the people in China.

The quarantine and lockdown in Tibet because of COVID-19 came at an already sensitive political time, in the buildup to Tibetan New Year (Losar) from February 24 as well as the anniversary of the March 10 Uprising in 1959 and the wave of protests across Tibet on the same date in 2008. Every year since 2008, the TAR has been closed off to foreigners for at least one month at around this time, with the closure in 2019 lasting from January 30 until April 1.[1] The annual closures of the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) are integral elements of the approach of the Chinese government to restrict access to Tibet for independent observers in order to maintain an iron grip in the region while at the same time avoiding any form of external scrutiny.

Chinese authorities have used their existing “grid management” network of total surveillance and tens of thousands of Party cadres in TAR to enforce control and quarantine measures, taking every opportunity to ensure praise for the Communist Party. In February, flights to Tibet were cut to almost nil,[2] and Tibetans marked Losar (Tibetan New Year) this year mostly at home, with streets and temples deserted rather than thronged with Chinese tourists as they have been in recent years.

In December 2018, U.S. President Donald Trump signed into law the Reciprocal Access to Tibet Act (RATA), the first major legislation on Tibet passed by the United States Congress since the Tibetan Policy Act of 2002 (TPA), indicative of the high level of support for Tibet in the U.S. This was followed by the passing in January 2020 in the U.S. House of Representatives of the Tibetan Policy and Support Act (TPSA), which will dramatically upgrade US political and humanitarian support for Tibetans, including sanctioning Chinese officials for interfering in the Dalai Lama’s succession.

The landmark bipartisan RATA legislation represents an important step towards holding China accountable for its policies on Tibet.

There is now an increasing awareness at European Union level of the importance of reciprocity, not only with regard to trade and economic relations, but also more generally relating to access to Tibet. Accordingly, there are moves to develop legislation in Europe, similar to the one in the United States.

RATA seeks to address the difficulties in access to the isolated and oppressed region for American diplomats, NGO workers, journalists, and all citizens whom Chinese authorities prevent from traveling freely. The Act makes it possible to deny U.S. entry to Chinese officials who are involved in policies that ultimately prohibit American citizens from access to Tibet.

The International Campaign for Tibet (ICT) has documented how multiple visits of diplomatic personnel, journalists and intergovernmental organizations from across the world to Tibet have been refused or blocked in recent years, in contravention of usual diplomatic practice between countries.

Today, the developments connected to the COVID-19 pandemic on the international stage show the determination of the Chinese Communist Party state to suppress the free flow of information and to silence the people in China.

The quarantine and lockdown in Tibet because of COVID-19 came at an already sensitive political time, in the buildup to Tibetan New Year (Losar) from February 24 as well as the anniversary of the March 10 Uprising in 1959 and the wave of protests across Tibet on the same date in 2008. Every year since 2008, the TAR has been closed off to foreigners for at least one month at around this time, with the closure in 2019 lasting from January 30 until April 1.[1] The annual closures of the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) are integral elements of the approach of the Chinese government to restrict access to Tibet for independent observers in order to maintain an iron grip in the region while at the same time avoiding any form of external scrutiny.

Chinese authorities have used their existing “grid management” network of total surveillance and tens of thousands of Party cadres in TAR to enforce control and quarantine measures, taking every opportunity to ensure praise for the Communist Party. In February, flights to Tibet were cut to almost nil,[2] and Tibetans marked Losar (Tibetan New Year) this year mostly at home, with streets and temples deserted rather than thronged with Chinese tourists as they have been in recent years.

SUMMARY

SUMMARY

“The passing of the Reciprocal Access to Tibet Act has been an important milestone towards a more robust approach to the PRC, based on the growing awareness that China’s increasing authoritarian influence has the capacity to subvert and shape our own democracies in ways that pose a real threat to our future.”

– Matteo Mecacci, President of the International Campaign for Tibet

“The passing of the Reciprocal Access to Tibet Act has been an important milestone towards a more robust approach to the PRC, based on the growing awareness that China’s increasing authoritarian influence has the capacity to subvert and shape our own democracies in ways that pose a real threat to our future.”

– Matteo Mecacci, President of the International Campaign for Tibet

This ICT report highlights moves towards targeting the lack of reciprocity in EU-China relations with regard to access to Tibet, outlining the following:

- No other province-level area in the PRC has equivalent barriers to access as the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR). This is most evident every year in March, when the Tibet Autonomous Region is closed to foreigners coinciding with the anniversary of the March 10 Uprising in 1959 and protests in 2008. This year, a more universal lockdown across the PRC due to the coronavirus was implemented.

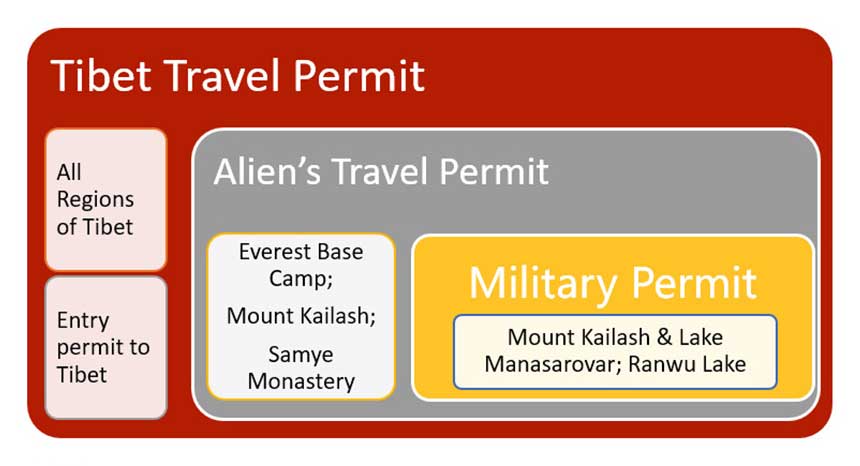

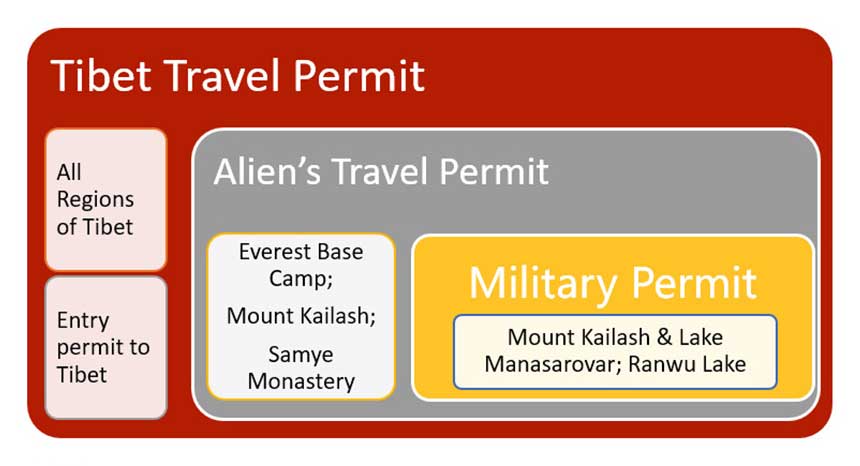

- The TAR is currently the only area for which the PRC requires a separate permit for foreign travelers, including foreign residents and foreign journalists or diplomats based in China. Such permits are routinely denied. Tibetan Americans also face denial of visas to visit their homeland on family visits, which is mentioned in the Reciprocal Access to Tibet Act. Tibetans in Europe face the same issue, and are subject to intense pressure and scrutiny from Party officials in the process of obtaining a Chinese visa. China has stepped up its efforts to influence Tibetans in Europe, seeking to impose a false narrative using a mix of threats and incentives.

- Chinese authorities intensified their propaganda drive and promotion of Tibet as “open” still further in 2019, seeking to obscure their covert and coercive policies, while at the same time restricting meaningful engagement with the situation on the ground for journalists and governments. The PRC authorities have weaponized the issue of access to Tibet, with access granted only on its own specific terms, and with different conditions to the rest of the PRC. Denying access, or threatening to do so, is used as a means of shutting down critique by government officials, scholars, journalists and independent experts.

- In 2019 rapidly expanding surveillance and an oppressive climate of fear drove deterioration in the work environment for foreign journalists, and there was a downward trend in organized press visits permitted by the authorities to Tibet. The Foreign Correspondents Club of China (FCCC) reported in 2018 “the darkest picture of reporting conditions inside China in recent memory,” and this has continued throughout 2019, with even fewer media visits possible.

- As the diplomatic focus on reciprocal access has gained attention, China has heightened its propaganda efforts on Tibet by sending official Tibetan delegations to foreign capitals to attack the Dalai Lama and gain support for its representations of Tibet. Over the past decade nearly three times the number of Party state organized delegations visited Western countries compared to Western government representatives allowed access to Tibet. In 2019, this continued to be a priority of the Chinese Communist Party, with a particular focus on its efforts to control the succession of the Dalai Lama, in response to an increasing international pushback on this issue as governments assert the Dalai Lama’s legitimacy over Beijing’s. While there was a small downturn in visits of Chinese delegations telling their version of Tibet’s story to Europe compared to 2018, hardly any foreign governments were hosted in Tibet.

- No access was possible in 2019 for any United Nations (UN) experts and special rapporteurs to Tibet, despite repeated requests. Following requests since the fire at the Jokhang Temple in Lhasa in February, 2018,[3] a “Reactive Monitoring Mission” to Lhasa by UNESCO took place from April 8 to 15, 2019, and was kept under wraps by the global heritage body. Its mission report has still not been released, more than a year later, and despite the outstanding significance of the sites in Tibet’s historic and cultural capital.

- Mass Chinese domestic tourism and foreign tourists to Tibet have been coexisting with the untrammeled powers of a security state engaged in the most widespread political crackdown in a generation. In contrast to the situation in Xinjiang (known to Uyghurs as East Turkestan), in 2019, China announced a dramatic spike in the number of foreign tourists visiting the Tibetan plateau, indicating a high level of confidence in covering up the human rights situation to visitors from outside the PRC, and ambitious new plans to attract Chinese tourists and promote “Third Pole Tibet” as a new tourist “brand.”

- Risks to American and European citizens of travelling in the PRC in general increased in 2019, linked to China’s shifting political agenda against their countries of origin. The dangers of access to both Xinjiang and Tibet for foreign visitors were first highlighted in the U.S. State Department’s China Travel Advisory in 2018, following the detention of two Canadians, former diplomat Michael Kovrig and businessman Michael Spavor, in the wake of the controversial arrest of a Huawei executive in Canada in December, 2017 – a disturbing indicator of China’s interpretation of “reciprocity.”

- While Chinese tourists are increasingly free to come and go to the plateau, Tibetans themselves face unprecedented restrictions on their movement. Ongoing restrictions imposed by the Party state also leave Tibetans locked in virtual isolation from the global community, unable to travel, even when they are able to obtain Chinese passports and scholarships abroad, which is rare. Tibetans face some of the most severe penalties anywhere for expressing views that differ from those of the Party state, no matter how moderate. While Chinese policy statements refer to the need to increase availability of propaganda materials in the Tibetan language, there has been a steady trend of the criminalization of integral elements of Tibetan identity and culture particularly targeting Tibetan efforts to promote and speak their mother tongue. Xi Jinping’s “new era” approach involves a dramatic downturn in any support for protections of minority “ethnic” culture.

- Increasing numbers of Tibetan exiles who wish to return to see families such as elderly parents are compromised and at risk from the surveillance state, and there are intensified efforts to influence a younger generation of Tibetans born to parents in exile in a bid to instill “the red gene” and replace memories or awareness of what families have lived through over 60 years of Chinese rule. Visits of Tibetans from abroad are institutionalized under the auspices of the hardline United Front Work Department (UFWD), which also attempts to work within communities in exile, seeking to influence and exacerbate divisions and convey propaganda messages.

Matteo Mecacci, President of the International Campaign for Tibet, said: “The passing of the Reciprocal Access to Tibet Act has been an important milestone towards a more robust approach to the PRC, based on the growing awareness that China’s increasing authoritarian influence has the capacity to subvert and shape our own democracies in ways that pose a real threat to our future. It will make Chinese officials directly responsible for Tibet policy and therefore for restricting foreign travelers’ access to Tibet ineligible for US visas, after an annual report assessing the degree of restrictions.

“Tibet’s geopolitical significance is such that it deserves greater prominence in global affairs. It is incumbent upon the European governments and the international community to now insist upon the principle of reciprocity in its dealings with the PRC, in order to address the asymmetry of authoritarian influence not only in Tibet but also on our own societies.”

This ICT report highlights moves towards targeting the lack of reciprocity in EU-China relations with regard to access to Tibet, outlining the following:

- No other province-level area in the PRC has equivalent barriers to access as the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR). This is most evident every year in March, when the Tibet Autonomous Region is closed to foreigners coinciding with the anniversary of the March 10 Uprising in 1959 and protests in 2008. This year, a more universal lockdown across the PRC due to the coronavirus was implemented.

- The TAR is currently the only area for which the PRC requires a separate permit for foreign travelers, including foreign residents and foreign journalists or diplomats based in China. Such permits are routinely denied. Tibetan Americans also face denial of visas to visit their homeland on family visits, which is mentioned in the Reciprocal Access to Tibet Act. Tibetans in Europe face the same issue, and are subject to intense pressure and scrutiny from Party officials in the process of obtaining a Chinese visa. China has stepped up its efforts to influence Tibetans in Europe, seeking to impose a false narrative using a mix of threats and incentives.

- Chinese authorities intensified their propaganda drive and promotion of Tibet as “open” still further in 2019, seeking to obscure their covert and coercive policies, while at the same time restricting meaningful engagement with the situation on the ground for journalists and governments. The PRC authorities have weaponized the issue of access to Tibet, with access granted only on its own specific terms, and with different conditions to the rest of the PRC. Denying access, or threatening to do so, is used as a means of shutting down critique by government officials, scholars, journalists and independent experts.

- In 2019 rapidly expanding surveillance and an oppressive climate of fear drove deterioration in the work environment for foreign journalists, and there was a downward trend in organized press visits permitted by the authorities to Tibet. The Foreign Correspondents Club of China (FCCC) reported in 2018 “the darkest picture of reporting conditions inside China in recent memory,” and this has continued throughout 2019, with even fewer media visits possible.

- As the diplomatic focus on reciprocal access has gained attention, China has heightened its propaganda efforts on Tibet by sending official Tibetan delegations to foreign capitals to attack the Dalai Lama and gain support for its representations of Tibet. Over the past decade nearly three times the number of Party state organized delegations visited Western countries compared to Western government representatives allowed access to Tibet. In 2019, this continued to be a priority of the Chinese Communist Party, with a particular focus on its efforts to control the succession of the Dalai Lama, in response to an increasing international pushback on this issue as governments assert the Dalai Lama’s legitimacy over Beijing’s. While there was a small downturn in visits of Chinese delegations telling their version of Tibet’s story to Europe compared to 2018, hardly any foreign governments were hosted in Tibet.

- No access was possible in 2019 for any United Nations (UN) experts and special rapporteurs to Tibet, despite repeated requests. Following requests since the fire at the Jokhang Temple in Lhasa in February, 2018,[3] a “Reactive Monitoring Mission” to Lhasa by UNESCO took place from April 8 to 15, 2019, and was kept under wraps by the global heritage body. Its mission report has still not been released, more than a year later, and despite the outstanding significance of the sites in Tibet’s historic and cultural capital.

- Mass Chinese domestic tourism and foreign tourists to Tibet have been coexisting with the untrammeled powers of a security state engaged in the most widespread political crackdown in a generation. In contrast to the situation in Xinjiang (known to Uyghurs as East Turkestan), in 2019, China announced a dramatic spike in the number of foreign tourists visiting the Tibetan plateau, indicating a high level of confidence in covering up the human rights situation to visitors from outside the PRC, and ambitious new plans to attract Chinese tourists and promote “Third Pole Tibet” as a new tourist “brand.”

- Risks to American and European citizens of travelling in the PRC in general increased in 2019, linked to China’s shifting political agenda against their countries of origin. The dangers of access to both Xinjiang and Tibet for foreign visitors were first highlighted in the U.S. State Department’s China Travel Advisory in 2018, following the detention of two Canadians, former diplomat Michael Kovrig and businessman Michael Spavor, in the wake of the controversial arrest of a Huawei executive in Canada in December, 2017 – a disturbing indicator of China’s interpretation of “reciprocity.”

- While Chinese tourists are increasingly free to come and go to the plateau, Tibetans themselves face unprecedented restrictions on their movement. Ongoing restrictions imposed by the Party state also leave Tibetans locked in virtual isolation from the global community, unable to travel, even when they are able to obtain Chinese passports and scholarships abroad, which is rare. Tibetans face some of the most severe penalties anywhere for expressing views that differ from those of the Party state, no matter how moderate. While Chinese policy statements refer to the need to increase availability of propaganda materials in the Tibetan language, there has been a steady trend of the criminalization of integral elements of Tibetan identity and culture particularly targeting Tibetan efforts to promote and speak their mother tongue. Xi Jinping’s “new era” approach involves a dramatic downturn in any support for protections of minority “ethnic” culture.

- Increasing numbers of Tibetan exiles who wish to return to see families such as elderly parents are compromised and at risk from the surveillance state, and there are intensified efforts to influence a younger generation of Tibetans born to parents in exile in a bid to instill “the red gene” and replace memories or awareness of what families have lived through over 60 years of Chinese rule. Visits of Tibetans from abroad are institutionalized under the auspices of the hardline United Front Work Department (UFWD), which also attempts to work within communities in exile, seeking to influence and exacerbate divisions and convey propaganda messages.

Matteo Mecacci, President of the International Campaign for Tibet, said: “The passing of the Reciprocal Access to Tibet Act has been an important milestone towards a more robust approach to the PRC, based on the growing awareness that China’s increasing authoritarian influence has the capacity to subvert and shape our own democracies in ways that pose a real threat to our future. It will make Chinese officials directly responsible for Tibet policy and therefore for restricting foreign travelers’ access to Tibet ineligible for US visas, after an annual report assessing the degree of restrictions.

“Tibet’s geopolitical significance is such that it deserves greater prominence in global affairs. It is incumbent upon the European governments and the international community to now insist upon the principle of reciprocity in its dealings with the PRC, in order to address the asymmetry of authoritarian influence not only in Tibet but also on our own societies.”

EUROPE AND ‘RECIPROCAL ACCESS’

EUROPE AND ‘RECIPROCAL ACCESS’

In 2019 the incarceration of more than a million Uyghurs, Kazakhs, etc., in Xinjiang brought human rights in China to the forefront of the international agenda, highlighting the deeply oppressive measures that were trialed first in TAR and the threat that China’s networked authoritarianism presents beyond its borders.[4]

Beijing is now confronting significant pressure and pushback from the international community, particularly the United States, over its business and political practices – compounded now by the international scrutiny faced by China’s leader Xi Jinping over his handling of the coronavirus crisis.

In this context, the concept of reciprocity is increasingly being cited by governments as an instrument for countering China’s one-way influence economic operations and in order to seek compliance with international standards and long-term mutual obligations, with evidence of an increasing awareness of the asymmetry in EU-China relations.

In September 2018, the European Parliament (EP) approved a report from MEP Bas Belder on the state of play of relations between the EU and China, which urged “China to give EU diplomats, journalists and citizens unfettered access to Tibet in reciprocity to the free and open access to the entire territories of the EU Member States that Chinese travellers enjoy; calls on the Chinese authorities to allow Tibetans in Tibet to travel freely and to respect their right to freedom of movement; urges the Chinese authorities to allow independent observers, including the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, to access Tibet; urges the EU institutions to take the issue of access to Tibet into serious consideration in the discussions on the EU-China visa facilitation agreement.”[5]

In March 2019, the European Commission set out a 10-point plan stating that China’s increasing presence in Europe “should be accompanied with greater reciprocity.” In a joint communication in March, 2019, the European Commission and the High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Federica Mogherini stated that: “The EU should robustly seek more balanced and reciprocal conditions governing the economic relationship [with China].”[6] The EU-China Strategy adopted in 2016 commits the EU to promoting “reciprocity, a level playing field and fair competition across all areas of co-operation with China.”[7]

In April 2019, Mogherini specifically stated at the plenary of the European Parliament that she had asked the Chinese authorities for reciprocal access to Tibet. She said, “Likewise, freedom of religion or belief is often violated in Tibet, and restrictions to access to the region are also in place. We have called on the Chinese authorities to allow reciprocal access to Tibet for European journalists, diplomats, and families.”[8]

Vice President Josep Borrell on behalf of the European Commission also said on March 9, 2020, “The Commission will continue to call on the Chinese authorities to allow reciprocal access to Tibet as part of the discussions in the Human Rights dialogue.”[9]

These developments, vigorously supported by ICT’s advocacy, represent an important step towards holding China accountable for its policies in Tibet, and recognizing that reciprocity is an important tenet of international relations, beyond trade, with the intention of promoting freedom of movement and an open and accessible Tibet for both American and European citizens and for Tibetans themselves, including the Dalai Lama, and Tibetans in the diaspora in Europe.

In 2019 the incarceration of more than a million Uyghurs, Kazakhs, etc., in Xinjiang brought human rights in China to the forefront of the international agenda, highlighting the deeply oppressive measures that were trialed first in TAR and the threat that China’s networked authoritarianism presents beyond its borders.[4]

Beijing is now confronting significant pressure and pushback from the international community, particularly the United States, over its business and political practices – compounded now by the international scrutiny faced by China’s leader Xi Jinping over his handling of the coronavirus crisis.

In this context, the concept of reciprocity is increasingly being cited by governments as an instrument for countering China’s one-way influence economic operations and in order to seek compliance with international standards and long-term mutual obligations, with evidence of an increasing awareness of the asymmetry in EU-China relations.

In September 2018, the European Parliament (EP) approved a report from MEP Bas Belder on the state of play of relations between the EU and China, which urged “China to give EU diplomats, journalists and citizens unfettered access to Tibet in reciprocity to the free and open access to the entire territories of the EU Member States that Chinese travellers enjoy; calls on the Chinese authorities to allow Tibetans in Tibet to travel freely and to respect their right to freedom of movement; urges the Chinese authorities to allow independent observers, including the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, to access Tibet; urges the EU institutions to take the issue of access to Tibet into serious consideration in the discussions on the EU-China visa facilitation agreement.”[5]

In March 2019, the European Commission set out a 10-point plan stating that China’s increasing presence in Europe “should be accompanied with greater reciprocity.” In a joint communication in March, 2019, the European Commission and the High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Federica Mogherini stated that: “The EU should robustly seek more balanced and reciprocal conditions governing the economic relationship [with China].”[6] The EU-China Strategy adopted in 2016 commits the EU to promoting “reciprocity, a level playing field and fair competition across all areas of co-operation with China.”[7]

In April 2019, Mogherini specifically stated at the plenary of the European Parliament that she had asked the Chinese authorities for reciprocal access to Tibet. She said, “Likewise, freedom of religion or belief is often violated in Tibet, and restrictions to access to the region are also in place. We have called on the Chinese authorities to allow reciprocal access to Tibet for European journalists, diplomats, and families.”[8]

Vice President Josep Borrell on behalf of the European Commission also said on March 9, 2020, “The Commission will continue to call on the Chinese authorities to allow reciprocal access to Tibet as part of the discussions in the Human Rights dialogue.”[9]

These developments, vigorously supported by ICT’s advocacy, represent an important step towards holding China accountable for its policies in Tibet, and recognizing that reciprocity is an important tenet of international relations, beyond trade, with the intention of promoting freedom of movement and an open and accessible Tibet for both American and European citizens and for Tibetans themselves, including the Dalai Lama, and Tibetans in the diaspora in Europe.

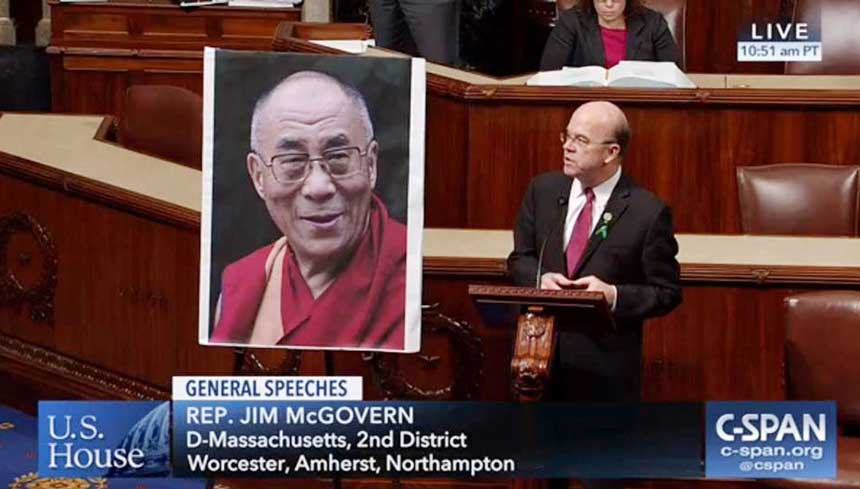

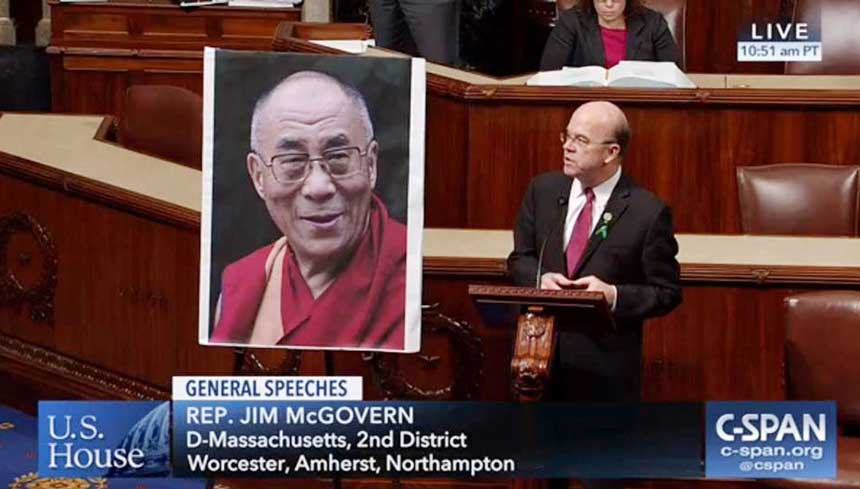

US Member of Congress Jim McGovern, who introduced the Reciprocal Access to Tibet, seen here delivering speaking in the Congress on the Dalai Lama and Tibet on December 14, 2017 on the subject, “Let His Holiness the Dalai Lama Go Home,” Representative McGovern said.

US Member of Congress Jim McGovern, who introduced the Reciprocal Access to Tibet, seen here delivering speaking in the Congress on the Dalai Lama and Tibet on December 14, 2017 on the subject, “Let His Holiness the Dalai Lama Go Home,” Representative McGovern said.

The signing into law of the Reciprocal Access to Tibet Act (RATA), after coordinated lobbying in Washington DC, undermined China’s intensive propaganda efforts to ensure it controls representations of Tibet – signaling that China’s claims have failed to convince. Representative Jim McGovern (D- Mass), who introduced the bill said: “For too long, China has covered up their human rights violations in Tibet by restricting travel. But actions have consequences, and today, we are one step closer to holding the Chinese officials who implement these restrictions accountable. I look forward to watching closely as our law is implemented, and continuing to stand with the people of Tibet in their struggle for religious and cultural freedom.”[10] The Chinese leadership was particularly vituperative in its response as a result. China “resolutely opposed” the law, Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying said on December 20, 2018, adding that it “sent seriously wrong signals to Tibetan separatist elements.”[11]

Tibet is not a marginal issue for the Chinese leadership. Xi Jinping’s sweeping political and strategic objectives in Tibet and the rise of a “control state,” in which the Party has an increasingly intrusive role in people’s everyday lives and beliefs reflect its prominence to the Communist Party leadership as an issue that is integral to China’s territorial concerns, the future of China’s economic expansion and the legitimacy of the Communist Party itself.

Beijing prioritizes campaigns directed against the Dalai Lama’s influence, Tibetan culture, and Tibetan religion, meaning that in recent years, almost any expression of Tibetan identity not directly sanctioned by the state can be branded as ‘separatist’ and penalized by a prison sentence or worse. This has been a cause of widespread anguish among Tibetans and a contributing factor in the wave of self-immolations that has taken place across Tibet since 2009.

China’s hostile response to the signing into law of RATA also involved attacks on the Dalai Lama, which were also linked to the 60th anniversary in March 2019 of his escape into exile in 1959, which was marked by Tibetan communities and supporters worldwide.

State media publication the Global Times, whose English-language version targets an international audience with an often aggressive message, published an article headlined “Tibet authorities lambast Dalai Lama in series of articles as US passes Tibet Reciprocal Access bill,” referring to unusually long editorials blaming the Dalai Lama for self-immolations across Tibet, as well as widespread protests that broke out in Tibet in 2008.[12] The articles, the first of which was published on the front page of Tibet Daily on December 12 (2018), were subsequently distributed by the TAR Justice department, coinciding with international coverage of the passing of RATA.

The attacks in the Tibet Daily editorials took the standard and extreme official line of blaming the Dalai Lama for being “prime leader of separatist political groups pursuing ‘Tibet independence,’ the loyal tool of international anti-China forces, the root cause of social unrest in Tibet, the biggest obstacle for Tibetan Buddhism to establish normal order and a politician under the disguise of religion.” It reiterated accusations made by the Chinese leadership at the height of the wave of self-immolations in Tibet blaming the Dalai Lama, saying that he “also violated the essential religious doctrine of ‘loving kindness and compassion’ by inciting religious believers to self-immolate.”[13]

The signing into law of the Reciprocal Access to Tibet Act (RATA), after coordinated lobbying in Washington DC, undermined China’s intensive propaganda efforts to ensure it controls representations of Tibet – signaling that China’s claims have failed to convince. Representative Jim McGovern (D- Mass), who introduced the bill said: “For too long, China has covered up their human rights violations in Tibet by restricting travel. But actions have consequences, and today, we are one step closer to holding the Chinese officials who implement these restrictions accountable. I look forward to watching closely as our law is implemented, and continuing to stand with the people of Tibet in their struggle for religious and cultural freedom.”[10] The Chinese leadership was particularly vituperative in its response as a result. China “resolutely opposed” the law, Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying said on December 20, 2018, adding that it “sent seriously wrong signals to Tibetan separatist elements.”[11]

Tibet is not a marginal issue for the Chinese leadership. Xi Jinping’s sweeping political and strategic objectives in Tibet and the rise of a “control state,” in which the Party has an increasingly intrusive role in people’s everyday lives and beliefs reflect its prominence to the Communist Party leadership as an issue that is integral to China’s territorial concerns, the future of China’s economic expansion and the legitimacy of the Communist Party itself.

Beijing prioritizes campaigns directed against the Dalai Lama’s influence, Tibetan culture, and Tibetan religion, meaning that in recent years, almost any expression of Tibetan identity not directly sanctioned by the state can be branded as ‘separatist’ and penalized by a prison sentence or worse. This has been a cause of widespread anguish among Tibetans and a contributing factor in the wave of self-immolations that has taken place across Tibet since 2009.

China’s hostile response to the signing into law of RATA also involved attacks on the Dalai Lama, which were also linked to the 60th anniversary in March 2019 of his escape into exile in 1959, which was marked by Tibetan communities and supporters worldwide.

State media publication the Global Times, whose English-language version targets an international audience with an often aggressive message, published an article headlined “Tibet authorities lambast Dalai Lama in series of articles as US passes Tibet Reciprocal Access bill,” referring to unusually long editorials blaming the Dalai Lama for self-immolations across Tibet, as well as widespread protests that broke out in Tibet in 2008.[12] The articles, the first of which was published on the front page of Tibet Daily on December 12 (2018), were subsequently distributed by the TAR Justice department, coinciding with international coverage of the passing of RATA.

The attacks in the Tibet Daily editorials took the standard and extreme official line of blaming the Dalai Lama for being “prime leader of separatist political groups pursuing ‘Tibet independence,’ the loyal tool of international anti-China forces, the root cause of social unrest in Tibet, the biggest obstacle for Tibetan Buddhism to establish normal order and a politician under the disguise of religion.” It reiterated accusations made by the Chinese leadership at the height of the wave of self-immolations in Tibet blaming the Dalai Lama, saying that he “also violated the essential religious doctrine of ‘loving kindness and compassion’ by inciting religious believers to self-immolate.”[13]

DELEGATION VISITS SEEK TO DOMINATE DISCOURSE ON TIBET

DELEGATION VISITS SEEK TO DOMINATE DISCOURSE ON TIBET

Handpicked government delegation visits are managed by the Chinese authorities as part of the “please come in, then go and tell the world” approach (the literal translation is “Please come in,” or “Welcome to enter,” then “Go out”).[14]

Handpicked government delegation visits are managed by the Chinese authorities as part of the “please come in, then go and tell the world” approach (the literal translation is “Please come in,” or “Welcome to enter,” then “Go out”).[14]

Nyima Tsering (3rd R, front), deputy director of the Standing Committee of the Tibet Autonomous Regional People’s Congress, at the European Parliament in Brussels, Belgium, on Oct. 15, 2019.

Nyima Tsering (3rd R, front), deputy director of the Standing Committee of the Tibet Autonomous Regional People’s Congress, at the European Parliament in Brussels, Belgium, on Oct. 15, 2019.

This is an integral part of a global strategy by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) not only to hide the realities of what is happening in Tibet today, but to dominate and control discourse and further its political agenda and power. While projected as “soft power,” this can be more accurately termed as the implementation of “sharp power,” which “In the new competition that is under way between autocratic and democratic states […] should be seen as the tip of [the CCP’s] dagger—or indeed as their syringe.”[15]

Aggressive warnings and attempts to control who European governments meet are a consistent feature. During a recent visit of an official Tibetan delegation to Brussels, Belgian Parliamentarians were warned “not to allow leaders of the Dalai group to visit Belgium, nor to provide any support for or facilitate the Dalai group’s anti-China separatist activities, and to work with China to maintain a healthy and stable development of China-Belgium relationships.”[16]

This is an integral part of a global strategy by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) not only to hide the realities of what is happening in Tibet today, but to dominate and control discourse and further its political agenda and power. While projected as “soft power.” this can be more accurately termed as the implementation of “sharp power,” which “In the new competition that is under way between autocratic and democratic states […] should be seen as the tip of [the CCP’s] dagger—or indeed as their syringe.”[15]

Aggressive warnings and attempts to control who European governments meet are a consistent feature. During a recent visit of an official Tibetan delegation to Brussels, Belgian Parliamentarians were warned “not to allow leaders of the Dalai group to visit Belgium, nor to provide any support for or facilitate the Dalai group’s anti-China separatist activities, and to work with China to maintain a healthy and stable development of China-Belgium relationships.”[16]

Norbu Dondrup, member of the Tibet Autonomous Regional People’s Congress and vice chairman of the regional government, with Vice President of the Chamber of Representatives of Belgium Andre Flahaut in Brussels on Dec. 12, 2019.

Norbu Dondrup, member of the Tibet Autonomous Regional People’s Congress and vice chairman of the regional government, with Vice President of the Chamber of Representatives of Belgium Andre Flahaut in Brussels on Dec. 12, 2019.

As part of the same process, Chinese government officials, scholars, and religious figures holding official titles are sent across the world to spread China’s official message on Tibet. ICT monitored 55 such official groups from 2009 to early 2018, with the highest number of 10 delegations in this ten-year period travelling to Europe, Argentina, Mongolia, Russia, Japan and other countries in 2017. This is nearly three times as many as the 20 official foreign government delegations permitted to travel to Tibet in the same period, according to ICT’s monitoring.[17]

While the US received most of the delegations in the decade from 2008 to 2018, ICT monitored a high number of delegations to EU countries, particularly Britain (five Tibet-related delegations), France, Spain (which each received four delegations) and Germany (three official delegations). In 2019, fewer Chinese delegations promoting the official line on Tibet were sent to the EU than the year before, and those who visited targeted specific countries. The major delegation visits consisted of a National People’s Congress (NPC) group from Lhasa to Brussels and the Belgian Parliament in December, a year after a similar visit by representatives from Tibet’s NPC in December 2018, and a different Tibetan “cultural delegation” that went to the European Parliament in October,[18] also visiting France, taking in the French Senate, the Netherlands (including the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs), Switzerland[19] and Lithuania.[20]

Analysis of the Tibet-related Chinese delegations to the West reveals a political agenda often based on Tibet visits or criticism of China’s policies by host governments, and also connected to visits by Tibetan Parliamentarians in exile and the Sikyong (President of the Central Tibetan Administration) Lobsang Sangay – for instance linked to the latter’s visits to the Belgian Parliament, the French Senate, and Lithuania. Previously, official Chinese delegations have coincided with the Dalai Lama’s overseas trips to these countries, in largely unsuccessful attempts to undermine and undercut his message, but this has been less visible in 2019, as the Dalai Lama did not make foreign trips.

As part of the same process, Chinese government officials, scholars, and religious figures holding official titles are sent across the world to spread China’s official message on Tibet. ICT monitored 55 such official groups from 2009 to early 2018, with the highest number of 10 delegations in this ten-year period travelling to Europe, Argentina, Mongolia, Russia, Japan and other countries in 2017. This is nearly three times as many as the 20 official foreign government delegations permitted to travel to Tibet in the same period, according to ICT’s monitoring.[17]

While the US received most of the delegations in the decade from 2008 to 2018, ICT monitored a high number of delegations to EU countries, particularly Britain (five Tibet-related delegations), France, Spain (which each received four delegations) and Germany (three official delegations). In 2019, fewer Chinese delegations promoting the official line on Tibet were sent to the EU than the year before, and those who visited targeted specific countries. The major delegation visits consisted of a National People’s Congress (NPC) group from Lhasa to Brussels and the Belgian Parliament in December, a year after a similar visit by representatives from Tibet’s NPC in December 2018, and a different Tibetan “cultural delegation” that went to the European Parliament in October,[18] also visiting France, taking in the French Senate, the Netherlands (including the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs), Switzerland[19] and Lithuania.[20]

Analysis of the Tibet-related Chinese delegations to the West reveals a political agenda often based on Tibet visits or criticism of China’s policies by host governments, and also connected to visits by Tibetan Parliamentarians in exile and the Sikyong (President of the Central Tibetan Administration) Lobsang Sangay – for instance linked to the latter’s visits to the Belgian Parliament, the French Senate, and Lithuania. Previously, official Chinese delegations have coincided with the Dalai Lama’s overseas trips to these countries, in largely unsuccessful attempts to undermine and undercut his message, but this has been less visible in 2019, as the Dalai Lama did not make foreign trips.

A Chinese delegation on Tibetan studies meeting scholars from Leiden University in the Hague, the Netherlands, on May 25, 2018.

A Chinese delegation on Tibetan studies meeting scholars from Leiden University in the Hague, the Netherlands, on May 25, 2018.

The visits of such delegations can also reflect efforts to create divisions between specific governments in terms of an approach to China – for instance, between member states of the European Union who may show differing levels of public support to Tibet and the Dalai Lama.

The Chinese Embassy vociferously condemned the Sikyong’s visit to Lithuania in May, 2019, describing it as a “serious political incident.”[21] China has been carefully cultivating the Baltic States with MPs from Lithuania and Latvia travelling to Tibet in August 2018, despite concern; the Baltic Times reported: “Lithuanian NGOs say the very fact that Lithuanian politicians will visit Tibet will demonstrate acceptance of Beijing’s order in this region.”[22]

In a similar timed intervention, the Chinese Embassy invited visitors to a screening of a propaganda film about life in Tibet at the same time as the World Parliamentarians’ Convention on Tibet in neighboring Riga, Latvia, in May, 2019.[23]

There is increasing alarm in EU member states over the operations of China’s state security, evident in an assessment by Lithuanian state security in 2019. “Growing China’s economic and political ambitions in the West resulted in the increasing aggressiveness of Chinese intelligence and security services’ activities not only in other NATO and EU countries, but also in Lithuania,” stated a National Threat Assessment carried out by the Lithuanian State Security Department in 2019.[24] The assessment continued: “Chinese intelligence looks for suitable targets – decision-makers, other individuals sympathizing with China and able to exert political leverage. They seek to influence such individuals by giving gifts, paying for trips to China, covering expenses of training and courses organized there. Chinese intelligence officers treat those gifts as a commitment to support political decisions favorable to China. Chinese intelligence-funded trips to China are used to recruit Lithuanian citizens. Given the growing threat posed by Chinese intelligence and security services in NATO and EU countries, their activity in Lithuania in the long term is also likely to expand.” The report makes specific mention of China’s specific agenda in influencing over Tibet, stating: “Primarily, China’s domestic policy issues drive Chinese intelligence activities in Lithuania. For example, it seeks that Lithuania would not support independence of Tibet and Taiwan and would not address these issues at the international level.”

In Australia, intelligence chiefs have sounded the alarm over a systematic Chinese government campaign of espionage and influence peddling that has led to fears over an erosion of Australian sovereignty, while in New Zealand, which also received a TAR delegation in 2018, scholars and government ministers have drawn attention to a disturbing expansion of political influence activities by China, connected to both the CCP government’s domestic pressures and foreign agenda. As with Lithuania and elsewhere, analysts in both countries note that a high priority is silencing critique on sensitive political issues such as Tibet or Taiwan.

China’s state media claims that the purpose of its delegations is to “dispel Tibet-related myths with truth and facts. These delegations have used vivid examples and statistics to confront foreign politicians, scholars and Tibet secessionists.”[25] The official press admits to mixed success with the delegations, stating: “Although those delegates have successfully discredited many rumors and helped eliminate prejudice held by many Western scholars and politicians against Tibet, the process has not always been smooth.”[26]

Accounts from Western politicians who meet such delegations give a very different picture. Belgian MP Samuel Cogolati, Vice President of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the House of Representatives, told ICT: “The meeting [with a Chinese delegation in December 2019] presented a window of opportunity to question the CCP about the situation in Tibet. Nevertheless, the meeting was confined to a long monologue on the ‘benefits’ of communism in Tibet. The Belgian parliamentarians were very disappointed not to receive any opportunity to question the Chinese representatives — especially given the lack of objectivity in the information provided.”

“For instance, Chinese representatives did not review the case of Gedun Choekyi Nyima [the Panchen Lama, in the custody of the Chinese government since 1995]. They only claimed that the Dalai Lama’s succession was a matter of Chinese domestic law and that no foreign state had [the right] to express itself on the subject. In addition, Chinese representatives defined themselves as those who protected Tibetan religious practices and claimed that it was the Dalai Lama who refused to comply with these practices. Moreover, the Chinese representatives spoke in Chinese but stated at the beginning of their presentation that they also spoke Tibetan.”[27]

Various Chinese officials have been prominent in overseas propaganda visits to the U.S. and other countries in the last few years; one of them is Lobsang Gyaltsen (rendered in different ways in Chinese media including ‘Losang Jamcan’) head of the Standing Committee of the Tibet Autonomous Region People’s Congress. Lobsang Gyaltsen has led delegations to the U.S. and in 2018 travelled to Belgium, Denmark and the Netherlands, where he made particularly strident criticisms of the Dalai Lama. In a visit to Europe made in the same month as the passing of RATA into law in December 2018, Lobsang Gyaltsen told Danish Parliamentarians that he hoped they would “recognize the Dalai Lama’s anti-China separatist nature,” taking the hardline approach of stating that: “The contradiction between us and Dalai group is neither a national or religious issue, nor a human rights issue, but a major issue of principle concerning national sovereignty and territorial integrity.”[28]

The visits of such delegations can also reflect efforts to create divisions between specific governments in terms of an approach to China – for instance, between member states of the European Union who may show differing levels of public support to Tibet and the Dalai Lama.

The Chinese Embassy vociferously condemned the Sikyong’s visit to Lithuania in May, 2019, describing it as a “serious political incident.”[21] China has been carefully cultivating the Baltic States with MPs from Lithuania and Latvia travelling to Tibet in August 2018, despite concern; the Baltic Times reported: “Lithuanian NGOs say the very fact that Lithuanian politicians will visit Tibet will demonstrate acceptance of Beijing’s order in this region.”[22]

In a similar timed intervention, the Chinese Embassy invited visitors to a screening of a propaganda film about life in Tibet at the same time as the World Parliamentarians’ Convention on Tibet in neighboring Riga, Latvia, in May, 2019.[23]

There is increasing alarm in EU member states over the operations of China’s state security, evident in an assessment by Lithuanian state security in 2019. “Growing China’s economic and political ambitions in the West resulted in the increasing aggressiveness of Chinese intelligence and security services’ activities not only in other NATO and EU countries, but also in Lithuania,” stated a National Threat Assessment carried out by the Lithuanian State Security Department in 2019.[24] The assessment continued: “Chinese intelligence looks for suitable targets – decision-makers, other individuals sympathizing with China and able to exert political leverage. They seek to influence such individuals by giving gifts, paying for trips to China, covering expenses of training and courses organized there. Chinese intelligence officers treat those gifts as a commitment to support political decisions favorable to China. Chinese intelligence-funded trips to China are used to recruit Lithuanian citizens. Given the growing threat posed by Chinese intelligence and security services in NATO and EU countries, their activity in Lithuania in the long term is also likely to expand.” The report makes specific mention of China’s specific agenda in influencing over Tibet, stating: “Primarily, China’s domestic policy issues drive Chinese intelligence activities in Lithuania. For example, it seeks that Lithuania would not support independence of Tibet and Taiwan and would not address these issues at the international level.”

In Australia, intelligence chiefs have sounded the alarm over a systematic Chinese government campaign of espionage and influence peddling that has led to fears over an erosion of Australian sovereignty, while in New Zealand, which also received a TAR delegation in 2018, scholars and government ministers have drawn attention to a disturbing expansion of political influence activities by China, connected to both the CCP government’s domestic pressures and foreign agenda. As with Lithuania and elsewhere, analysts in both countries note that a high priority is silencing critique on sensitive political issues such as Tibet or Taiwan.

China’s state media claims that the purpose of its delegations is to “dispel Tibet-related myths with truth and facts. These delegations have used vivid examples and statistics to confront foreign politicians, scholars and Tibet secessionists.”[25] The official press admits to mixed success with the delegations, stating: “Although those delegates have successfully discredited many rumors and helped eliminate prejudice held by many Western scholars and politicians against Tibet, the process has not always been smooth.”[26]

Accounts from Western politicians who meet such delegations give a very different picture. Belgian MP Samuel Cogolati, Vice President of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the House of Representatives, told ICT: “The meeting [with a Chinese delegation in December 2019] presented a window of opportunity to question the CCP about the situation in Tibet. Nevertheless, the meeting was confined to a long monologue on the ‘benefits’ of communism in Tibet. The Belgian parliamentarians were very disappointed not to receive any opportunity to question the Chinese representatives — especially given the lack of objectivity in the information provided.”

“For instance, Chinese representatives did not review the case of Gedun Choekyi Nyima [the Panchen Lama, in the custody of the Chinese government since 1995]. They only claimed that the Dalai Lama’s succession was a matter of Chinese domestic law and that no foreign state had [the right] to express itself on the subject. In addition, Chinese representatives defined themselves as those who protected Tibetan religious practices and claimed that it was the Dalai Lama who refused to comply with these practices. Moreover, the Chinese representatives spoke in Chinese but stated at the beginning of their presentation that they also spoke Tibetan.”[27]

Various Chinese officials have been prominent in overseas propaganda visits to the U.S. and other countries in the last few years; one of them is Lobsang Gyaltsen (rendered in different ways in Chinese media including ‘Losang Jamcan’) head of the Standing Committee of the Tibet Autonomous Region People’s Congress. Lobsang Gyaltsen has led delegations to the U.S. and in 2018 travelled to Belgium, Denmark and the Netherlands, where he made particularly strident criticisms of the Dalai Lama. In a visit to Europe made in the same month as the passing of RATA into law in December 2018, Lobsang Gyaltsen told Danish Parliamentarians that he hoped they would “recognize the Dalai Lama’s anti-China separatist nature,” taking the hardline approach of stating that: “The contradiction between us and Dalai group is neither a national or religious issue, nor a human rights issue, but a major issue of principle concerning national sovereignty and territorial integrity.”[28]

Lobsang Gyaltsen (2nd L), chairman of the Standing Committee of the Tibet Autonomous Regional People’s Congress, meeting scholars from Nordic Institute of Asian Studies at Copenhagen University in Copenhagen, Denmark, on Dec. 14, 2018.

Lobsang Gyaltsen (2nd L), chairman of the Standing Committee of the Tibet Autonomous Regional People’s Congress, meeting scholars from Nordic Institute of Asian Studies at Copenhagen University in Copenhagen, Denmark, on Dec. 14, 2018.

Lobsang Gyaltsen’s exhortations fell on deaf ears, particularly in the Netherlands given that his visit followed a teaching by the Dalai Lama, who spoke to a packed stadium and met Dutch Parliamentarians in Rotterdam in September, 2018.

Another prominent Tibetan official who has travelled to the U.S. and Europe on various occasions, although not in 2019, is Pema Thinley (Chinese: Baima Chilin), Vice Chair of the National People’s Congress Standing Committee. Pema Thinley, known for his hostile critique of the Dalai Lama, has spoken at think-tanks in Brussels[29] or in Swiss cities with uniform messages including that Tibet is “an inalienable part of China,” and that there is rapid economic progress and positive social change in Tibet.

The hosts in the West of these delegations, including respected scholarly institutions, think-tanks, and governments, may not always be aware that while their purpose is presented as engaging in dialogue (and while sometimes a level of engagement may indeed be possible), ultimately these delegations are part of China’s strategic information operations, reflecting the vigorous propaganda efforts of the United Front Work Department. Official Chinese delegations to the West are tightly controlled, and every intention is made to ensure they have the opportunity to issue boilerplate statements without challenge at non-public events. Meetings with ordinary Tibetans in the diaspora who might raise sensitive questions are avoided, and mostly governments and even civil society and academic hosts concede to their specifications.

Lobsang Gyaltsen’s exhortations fell on deaf ears, particularly in the Netherlands given that his visit followed a teaching by the Dalai Lama, who spoke to a packed stadium and met Dutch Parliamentarians in Rotterdam in September, 2018.

Another prominent Tibetan official who has travelled to the U.S. and Europe on various occasions, although not in 2019, is Pema Thinley (Chinese: Baima Chilin), Vice Chair of the National People’s Congress Standing Committee. Pema Thinley, known for his hostile critique of the Dalai Lama, has spoken at think-tanks in Brussels[29] or in Swiss cities with uniform messages including that Tibet is “an inalienable part of China,” and that there is rapid economic progress and positive social change in Tibet.

The hosts in the West of these delegations, including respected scholarly institutions, think-tanks, and governments, may not always be aware that while their purpose is presented as engaging in dialogue (and while sometimes a level of engagement may indeed be possible), ultimately these delegations are part of China’s strategic information operations, reflecting the vigorous propaganda efforts of the United Front Work Department. Official Chinese delegations to the West are tightly controlled, and every intention is made to ensure they have the opportunity to issue boilerplate statements without challenge at non-public events. Meetings with ordinary Tibetans in the diaspora who might raise sensitive questions are avoided, and mostly governments and even civil society and academic hosts concede to their specifications.

The Institute for Security and Development Policy in Stockholm organized a roundtable with a delegation from the Tibetan Academy of Social Sciences, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and the China Tibetology Research Center on June 25, 2018.

The Institute for Security and Development Policy in Stockholm organized a roundtable with a delegation from the Tibetan Academy of Social Sciences, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and the China Tibetology Research Center on June 25, 2018.

All of these efforts involve the same motivation; to change the story on Tibet. A close Tibetan observer of efforts by China’s United Front Work Department, the hardline Party department responsible for Tibetan affairs, said: “China is trying to change the story on Tibet. For 60 years, the world has known about the killings in Tibet, the oppression, the human rights abuses, and this information has been conveyed to governments and journalists through exile Tibetan representatives and rights groups across the globe. But China wants to change this story and create new narratives for Tibet in the 21st century based on progress, development, the ‘happiness’ of Tibetans under Chinese rule. This is the basis for their efforts with delegations overseas, with returned Tibetans and with governments worldwide.”

All of these efforts involve the same motivation; to change the story on Tibet. A close Tibetan observer of efforts by China’s United Front Work Department, the hardline Party department responsible for Tibetan affairs, said: “China is trying to change the story on Tibet. For 60 years, the world has known about the killings in Tibet, the oppression, the human rights abuses, and this information has been conveyed to governments and journalists through exile Tibetan representatives and rights groups across the globe. But China wants to change this story and create new narratives for Tibet in the 21st century based on progress, development, the ‘happiness’ of Tibetans under Chinese rule. This is the basis for their efforts with delegations overseas, with returned Tibetans and with governments worldwide.”

DALAI LAMA SUCCESSION THE “HOTTEST ISSUE”

DALAI LAMA SUCCESSION THE “HOTTEST ISSUE”

In January 2020, the U.S. House of Representatives voted overwhelmingly to approve the Tibetan Policy and Support Act, a comprehensive piece of legislation that will dramatically upgrade US political and humanitarian support for Tibetans, including the sanctioning of Chinese officials for interfering in the Dalai Lama’s succession.[30]

The U.S. is the only Western country to have support for Tibet enshrined in law with the Tibetan Policy Act of 2002, which requires the administration to report to Congress over the progress of dialogue between the Dalai Lama’s envoys and Beijing, as well as providing multi-million dollar funding annually for social, cultural and economic projects in Tibet and the Tibetan community in exile.

China’s state media have prioritized the issue of the Dalai Lama’s succession in its messaging over the past year, with the Global Times stating it was the “hottest issue” under discussion in 2019.[31] This is likely to reflect Beijing’s concern over increasing assertions globally of China’s lack of legitimacy in this matter, and support for the Dalai Lama.

Now there is growing interest in Europe in pushing back against China’s efforts to control representations of the Dalai Lama’s succession. In the first written policy statement by the Dutch government to include explicit language on Tibet, the Minister of Foreign Affairs in the Netherlands, Stef Blok, stated in November 2019: “The government is concerned about interference by the Chinese government in religious matters. According to the Chinese authorities, the reincarnation process is subject to Chinese legislation. The position of this cabinet is that it is up to the Tibetan religious community itself to appoint a future successor to the Dalai Lama.”[32]

The Dutch Foreign Affairs Ministry raised the following additional matters of concern: “The government also encourages China to remain in dialogue with representatives of the Tibetan community inside and outside of China. There is also increased police presence and surveillance in Tibet, particularly in urban areas and in and around temples. […] Other worrying developments include the partial demolition of the Tibetan monastery complex Larung Gar and the fact that the Tibetan language in compulsory education must increasingly give way to Mandarin. The government concludes that the Chinese policy in Tibet as a whole has a strongly restrictive effect on the religious and cultural freedoms in Tibet, as well as on the privacy of Tibetan Buddhists in particular.”

In response to a question from Member of Parliament Samuel Cogolati on his government’s position, Belgian Foreign Affairs and Defense Minister Philippe Goffin said in January 2020: “It is logically up to the Tibetan religious community to designate his successor without interference from the temporal authorities.”[33] In Germany, the Minister of State in the Foreign Office, Niels Annen, replying to a written question from parliament, stated that the German government “is of the opinion that religious communities may regulate their affairs autonomously.” Annen added, “This includes the right to determine their religious leaders themselves.”[34]

Several similar parliamentary questions have also been tabled in France by members of the Senate’s International Information Tibet Group, and the answer from the French government is pending.[35]

At the European level too, the issue has been gaining traction in recent months; in April 2020, replying to a written question submitted to him by five Members of the European Parliament, the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Vice President of the EU Commission Josep Borrell stated that the EU, in the framework of the EU-China Human Rights dialogue, “has consistently expressed the expectation that China will respect the succession of the Dalai Lama in accordance with Tibetan Buddhism norms,” and that it will “continue to express its position on this matter.”[36] Furthermore, in an opinion piece published in several European newspapers in May 2020, Borrell said that the focus of the EU-China relationship should be on “trust, transparency, and reciprocity.”[37]

In January 2020, the U.S. House of Representatives voted overwhelmingly to approve the Tibetan Policy and Support Act, a comprehensive piece of legislation that will dramatically upgrade US political and humanitarian support for Tibetans, including the sanctioning of Chinese officials for interfering in the Dalai Lama’s succession.[30]

The U.S. is the only Western country to have support for Tibet enshrined in law with the Tibetan Policy Act of 2002, which requires the administration to report to Congress over the progress of dialogue between the Dalai Lama’s envoys and Beijing, as well as providing multi-million dollar funding annually for social, cultural and economic projects in Tibet and the Tibetan community in exile.

China’s state media have prioritized the issue of the Dalai Lama’s succession in its messaging over the past year, with the Global Times stating it was the “hottest issue” under discussion in 2019.[31] This is likely to reflect Beijing’s concern over increasing assertions globally of China’s lack of legitimacy in this matter, and support for the Dalai Lama.

Now there is growing interest in Europe in pushing back against China’s efforts to control representations of the Dalai Lama’s succession. In the first written policy statement by the Dutch government to include explicit language on Tibet, the Minister of Foreign Affairs in the Netherlands, Stef Blok, stated in November 2019: “The government is concerned about interference by the Chinese government in religious matters. According to the Chinese authorities, the reincarnation process is subject to Chinese legislation. The position of this cabinet is that it is up to the Tibetan religious community itself to appoint a future successor to the Dalai Lama.”[32]

The Dutch Foreign Affairs Ministry raised the following additional matters of concern: “The government also encourages China to remain in dialogue with representatives of the Tibetan community inside and outside of China. There is also increased police presence and surveillance in Tibet, particularly in urban areas and in and around temples. […] Other worrying developments include the partial demolition of the Tibetan monastery complex Larung Gar and the fact that the Tibetan language in compulsory education must increasingly give way to Mandarin. The government concludes that the Chinese policy in Tibet as a whole has a strongly restrictive effect on the religious and cultural freedoms in Tibet, as well as on the privacy of Tibetan Buddhists in particular.”

In response to a question from Member of Parliament Samuel Cogolati on his government’s position, Belgian Foreign Affairs and Defense Minister Philippe Goffin said in January 2020: “It is logically up to the Tibetan religious community to designate his successor without interference from the temporal authorities.”[33] In Germany, the Minister of State in the Foreign Office, Niels Annen, replying to a written question from parliament, stated that the German government “is of the opinion that religious communities may regulate their affairs autonomously.” Annen added, “This includes the right to determine their religious leaders themselves.”[34]

Several similar parliamentary questions have also been tabled in France by members of the Senate’s International Information Tibet Group, and the answer from the French government is pending.[35]

At the European level too, the issue has been gaining traction in recent months; in April 2020, replying to a written question submitted to him by five Members of the European Parliament, the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Vice President of the EU Commission Josep Borrell stated that the EU, in the framework of the EU-China Human Rights dialogue, “has consistently expressed the expectation that China will respect the succession of the Dalai Lama in accordance with Tibetan Buddhism norms,” and that it will “continue to express its position on this matter.”[36] Furthermore, in an opinion piece published in several European newspapers in May 2020, Borrell said that the focus of the EU-China relationship should be on “trust, transparency, and reciprocity.”[37]

A PATTERN OF RESTRICTIONS IN ACCESS

A PATTERN OF RESTRICTIONS IN ACCESS

“I had expressed a wish to go to the countryside and visit a prison, for example, in the hope of learning a little more about the real conditions on site. Ultimately, we were suggested to visit numerous cultural venues, a religious pilgrimage site, a school and a former farming family. This program should certainly signal normalcy and success of China’s economic development policy. Nevertheless, everything was naturally organized by the Chinese side which accompanied us throughout the trip. In this respect, the insight into the conditions there was very limited.”

– Bärbel Kofler, German Human Rights Commissioner

“I had expressed a wish to go to the countryside and visit a prison, for example, in the hope of learning a little more about the real conditions on site. Ultimately, we were suggested to visit numerous cultural venues, a religious pilgrimage site, a school and a former farming family. This program should certainly signal normalcy and success of China’s economic development policy. Nevertheless, everything was naturally organized by the Chinese side which accompanied us throughout the trip. In this respect, the insight into the conditions there was very limited.”

– Bärbel Kofler, German Human Rights Commissioner

The most prominent European visit to Tibet over the past year was the German Human Rights Commissioner Bärbel Kofler, who travelled to Lhasa on December 5, 2018, after her request to visit Xinjiang was rejected by the Chinese government. This was most likely a reflection of the Chinese government’s confidence in securing full control in Tibet and ability to stage manage foreign delegations.

The most prominent European visit to Tibet over the past year was the German Human Rights Commissioner Bärbel Kofler, who travelled to Lhasa on December 5, 2018, after her request to visit Xinjiang was rejected by the Chinese government. This was most likely a reflection of the Chinese government’s confidence in securing full control in Tibet and ability to stage manage foreign delegations.

Germany’s Commissioner for Human Rights Policy and Humanitarian Aid Bärbel Kofler in Lhasa for the 15th China-Germany Human Rights Dialogue held from December 6 to 8, 2018. It was participated by officials of the Supreme People’s Court of China, the United Front Work Department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, the Ministry of Public Security of China, the Ministry of Justice of China.

Germany’s Commissioner for Human Rights Policy and Humanitarian Aid Bärbel Kofler in Lhasa for the 15th China-Germany Human Rights Dialogue held from December 6 to 8, 2018. It was participated by officials of the Supreme People’s Court of China, the United Front Work Department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, the Ministry of Public Security of China, the Ministry of Justice of China.

Upon return, Rights Commissioner Kofler described the human rights situation in Tibet as critical, highlighting the “the excessive controls, punishment of relatives for the crimes of family members, prohibition of normal religious freedom and patriotic education that are being carried out in Tibet even to this day.”[38] The German Human Rights Commissioner also referred to the difficulties in establishing the true conditions in Tibet, saying: “I had expressed a wish to go to the countryside and visit a prison, for example, in the hope of learning a little more about the real conditions on site. Ultimately, we were suggested to visit numerous cultural venues, a religious pilgrimage site, a school and a former farming family. This program should certainly signal normalcy and success of China’s economic development policy. Nevertheless, everything was naturally organized by the Chinese side which accompanied us throughout the trip. In this respect, the insight into the conditions there was very limited.”[39]

The coverage of the visit in the Chinese state media referred predictably to the “the outstanding achievements” of the Communist Party leadership under Xi Jinping in Tibet.[40] The German Human Rights Commissioner did not hold a press briefing in Beijing after the visit, as delegations to Tibet once used to do, reflecting the high levels of control by the Chinese authorities over messaging by foreign delegations.

European governments have raised concern about access, with the UK government stating that access to Tibet by all foreign passport holders is heavily restricted by the Chinese authorities, including journalists and that: “We continue to urge the Chinese authorities to lift the visit restrictions imposed on foreigners.” The then Minister of State for the Foreign and Commonwealth Office Mark Field said: “We have made repeated requests to the Chinese authorities to visit Tibet in the last 10 years, but very few of those have been agreed or acknowledged.”[41] The UK sent a delegation to Lhasa from their Beijing Embassy in July, 2019, their first visit since a joint trip with other EU Embassies in 2017.

In response to a question from a Parliamentarian about access to Tibet, the Latvian Foreign Ministry downplayed the issue by stating that: “In 2018, one request for a diplomat’s private trip was submitted to the TAR Foreign Affairs Office through the embassy, but no response was received. In 2017, the Ambassador of Latvia participated in the joint trip of the EU Ambassadors to the TAR, while in 2018, during the visit of the Baltic parliamentarians to China, several members of the Saeima visited the TAR.”[42]

In February 2020, in response to a Parliamentary question, the Danish government stated that the Foreign Policy Committee of the Parliament request to visit Tibet in June 2012 was rejected, but instead visited Qinghai (in its response, it appeared to be unaware that Tibet includes not only the TAR, but areas administered by the neighboring provinces of Qinghai, Sichuan, Yunnan and Gansu). The last official visit of Denmark’s Ambassador to China to the TAR was together with the group of EU ambassadors in Beijing, in June 2017.[43]

Delegations to Tibet in 2019 tended to be from “friendly” countries such as Nepal, which has shaped its foreign policy around China’s influence and investments, becoming a part of China’s strategic imperative to maintain and enforce control on Tibet’s borders. Engagement between the two countries has been stepped up since Nepal signed up to China’s One Belt One Road global infrastructure initiative, followed by a visit by China’s leader Xi Jinping to Kathmandu in October 2019. Visits included a delegation of Nepalese MPs to Tibet University in Lhasa in August 2018.[44]

The confidence of the Chinese authorities in showcasing Lhasa in particular after the protests and crackdown of 2008 is increasingly evident – for instance in its annual hosting of a Tourism Expo from 2014 onwards. In addition, the blunt propaganda exercise of the Lhasa Forum was repeated in 2019, with journalists from Italy, France and the UK in attendance and individuals from 37 different countries, according to the Chinese state media.[45] The Lhasa Forum seeks to secure the endorsement of foreign participants to China’s official line on Tibet’s development, using the timeworn tactic of manipulating foreign visitors through the use of access to an otherwise closed region.[46]