The Chinese Communist Party ordered a series of demolitions of structures of religious significance and detentions of Tibetans resisting them in Draggo (Chinese: Luhuo) County in eastern Tibet. The demolitions came a year after the CCP established in late 2020 “Xi Jinping Thought on Rule of Law as the guiding thought for law-based governance in China,” reflecting an even more repressive approach to Tibetan Buddhist religious practice that organizes itself outside CCP control.

The demolitions, which began in late October 2021, resulted in the destruction of three enormous Buddha statues, a row of 45 prayer wheels and a monastic school in the county between October and December 2021. Many local Tibetans who resisted or showed discontent toward the authorities were detained. Amid the information clampdown, the names of at least 11 Tibetan detainees could be ascertained, although the real number of detainees is believed to be much higher.

The Gaden Rabten Namgyal Ling monastic school was the first to be demolished, beginning on Oct. 31. Thereafter, a 99-foot enormous Buddha statue constructed in October 2015 was demolished beginning on Dec. 12. A 45-foot Guru Padmasambhava statue at Chanang Monastery, located 15 kilometers away from the 99-foot Buddha statue, was demolished around the same time. A three-story high (around 40-foot) Maitreya (future Buddha) statue housed inside Draggo Monastery was demolished beginning Dec. 21.

All the demolitions took place within a 15-kilometer radius between Oct. 31 and Dec. 21, 2021.

Detentions of Tibetans

Although the number of detentions related to the demolitions is believed to be much higher, names of at least 11 Tibetans could be ascertained from information published by multiple Tibetan exile media outlets and NGOs. They are:

- Pelga (abbot of Draggo monastery, male)

- Nyima (administrative head of Draggo monastery, male)

- Nyima (monk affiliated to Draggo monastery, male)

- Tashi Dorjee (monk affiliated to Draggo monastery, male)

- Tsering Samdup (lay person, male)

- Lhamo Yangkyi (female)

- Trolpa (son of a Thangka painter, male)

- Lobsang Tsomo (nun, female)

- Asang (female)

- Dotra (male)

- Nortso (female)

To date, Nyima (the administrative head of Draggo monastery) and Lobsang Tsomo (a nun) are known to have been released from detention, as reported by Radio Free Asia and Tibet Times, respectively. Lobsang Tsomo was released after serving three months in a “re-education center” in Dakyab county in the so-called Tibet Autonomous Region. Nyima was released after about four months of detention. The status of the remaining detainees is unknown.

The authorities detained the Tibetans for a variety of reasons ranging from communicating to the outside world to pinning photos of the statues as their social media profile pictures. For instance, Lobsang Tsomo and Tashi Dorjee were detained for communicating to their relatives or contacts abroad. Asang, Dotra and Nortso were detained for pinning photos of the statues as their profile pictures on WeChat, a Chinese social media app.

Left: A congregation of monks during the inauguration of the 99-foot Buddha statue on October 5, 2015. The statue was razed to the ground in December 2021.

Right: The 45-foot Guru Padmasambhava statue as depicted on right side of the web homepage of the three-centuries-old Chanang Monastery.

Left: Three-storey high Maitreya Buddha (future Buddha) statue housed inside Draggo Monastery before the demolition.

Right: Tearing down of the 1990 founded Gaden Rabten Namgyaling monastic school in progress.

The county government gave the local Tibetans the options of tearing down the school themselves and salvaging the construction materials, or the workers sent by the government would demolish the school with nothing left to salvage. The local Tibetans chose to tear it down themselves.

The ambitious new Draggo party secretary

The latest round of demolitions came after a new county Party Secretary, Wang Dongsheng, took charge of Draggo county. As the top CCP leader in the county, he would have issued the demolition order.

On Oct. 13, 2021, Wang Dongsheng’s appointment as the new Party Secretary was announced during the Draggo county leading cadres meeting. The 52-year-old Tibetan national, who goes by his Chinese name, had spent his entire 33-year career (he has been a CCP member since 1989) in eastern Tibet. Prior to his rise as Draggo county party secretary, he had assumed various party roles in his native Nyachukha (Yajiang), Lithang (Litang) and Serthar (Seda).

As the deputy party secretary of Serthar county before his current position, he oversaw the destruction of Larung Gar Buddhist Academy between 2016-17, resulting in the demolition of around 7,500 monastic dwelling huts and the expulsion of around 5,000 monastics. Wang Dongsheng exhibits all the attributes of a model Tibetan party leader fitting neatly into the central Chinese party leadership’s strategic move to utilize Tibetans to control Tibetans for a better effect of policy implementation and for the party’s domestic legitimacy.

Three days after his appointment as Draggo County Party Secretary, Wang Dongsheng led his team on a county inspection on Oct. 16, according to the county government website. The “supervision and research work” team consisted of Gou Fuhua who holds the concurrent post of county deputy governor and director of the county public security bureau, county Deputy Governor Tashi Rigpo (Zhaxi Rangbu), and the heads of the county development and reform bureau, ethnic and religious bureau, agriculture and animal husbandry bureau, and housing and urban development bureau, and other bureaus.

Draggo Party Secretary Wang Dongsheng inspection on October 16, 2021. (Source: Luhuo People’s Government)

The demolitions began soon after Wang’s inspection of the county ostensibly to carry out the central Chinese leadership’s emphasis on “law-based governance.”

“Law based governance” and “Xi Jinping Thought”

The county government’s 2021 annual report, published on Dec. 22, 2021 (see appendix 2 for text retrieved by the International Campaign for Tibet from the county government’s website before it was taken down) with oversight from Wang, stressed the rectification of deficiencies in the implementation of the party’s law-based governance strategy in the county. Although the report did not specifically mention or quantify removal of religious structures in the county, ICT believes that the demolitions were the effect of implementation of the governance policy per “Xi Jinping Thought on the Rule of Law.” The annual report outlines several – in the view of the county leadership – administrative shortcomings and calls for an even more repressive approach toward religious and lay communities in the county.

The first Chinese central conference on “law-based governance” in mid-November 2020 established “Xi Jinping Thought on the Rule of Law and its status as the guiding thought for law-based governance in China,” according to Chinese state media outlet Xinhua in December 2020. Unlike the principle of rule of law in the international arena, which requires meaningful restraint on state power and accountability of leaders and institutions to publicly promulgated law, law to the CCP is a tool and a means to justify and maintain party rule. Under Chinese President Xi Jinping’s leadership, “governing the country in accordance with law” or simply “law-based governance” (ambiguously formulated in English as rule of law) is a cornerstone of the party’s governance strategy.

The Draggo county report titled “Public Notification Regarding the 2021 Report on Building a Government Ruled by Law Working Situation” deplored the county cadres’ deficiencies and inefficiency in implementing the central leadership’s “law-based governance” strategy. The report called for the education of the cadres and also for updating their knowledge in accordance with the instructions by the central Chinese leadership. Pointing out that the “government departments mistakenly believe that administration according to law is theoretical work” and retreat work”, and that the rule of law thinking and rule of law concept are weak”, the report instructs special training on capacity building for administration according to law and lectures on the rule of law for the officials. The document also laid out the punishments and other consequences for lapses in administration and decision making.

The document laid out the key work arrangements for the construction of a so-called law-based government in 2021 by taking simultaneous multiple measures for “vigorously grasping implementation, and vigorously and orderly advancing all aspects of the building of a law-based government.” Citing the authority of Document No. 27 of the next higher level People’s Government of Kardze (Ganzi) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture titled “Key Work Arrangements for the Building of a Law based Government by the People’s Government of Ganzi Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in 2021,” emphasis is laid on standardization of law enforcement supervision and management in Draggo county government. For the strengthening of building of the law enforcement contingent, 49 legal review officers were attached to the county’s 28 administrative law enforcement departments for standardization between the county law enforcement departments in strict accordance with the prefecture, provincial and national level administrative law enforcement organs. The report also called to “establish and complete working mechanisms for legal advisers to attend relevant government meetings” and to “ensure that legal advisers play an active role in major administrative decisions and administration according to law.” In other words, the report strives to eliminate what is viewed as local government latitude in implementing the laws designed by the party leadership at the center for standardization across all levels of administrative organs.

In publicizing the Chinese central leadership’s emphasis on “law-based governance,” the report quantified the number of official visits to publicize “law-based government” across the county, which included the monasteries, the countryside, communities, enterprises and educational facilities. According to the document, the effort targeted more than 2,600 monastic population to receive legal education and publicity materials. Besides the monastic community, the report also stated that the officials went to the countryside 92 times and 32 times into the community, cumulatively covering 14,500 people; educational facilities were visited 12 times covering 1,900 people; enterprises were visited 16 times, covering 900 people with education and publicity materials. Cumulatively, the official publicity visits in 2021 covered 19,900 people in Draggo County or 42% of the county’s population. Based on the 2020 seventh national census, the county population was 47,185 with 12,989 categorized as urban and 34,196 as non-urban, according to the Draggo County People’s Government website.

Draggo county

Situated at the confluence of Zhechu and Nyichu rivers, Draggo (meaning head of the rock in Tibetan) County is a relatively small county in the Kardze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan. Draggo is a strongly Tibetan area in terms of culture and demography, despite increasing Chinese exploitation and migration into the town. With the extinction of the local ruler at the end of the 19th century, the Viceroy of Sichuan established a military colony in 1894. The colony was unsuccessful, but its Chinese name, “Luhuo,” continues to be used to date as a Chinese toponym in Chinese administrative divisions for Draggo County.

Draggo lies on the earthquake fault line, and the memory of a 1973 earthquake is still fresh in the minds of Draggo Tibetans. Although none of the recent earthquakes were as deadly as the 7.9 earthquake in February 1973 that killed over 2,200 residents, the county continues to be hit with quakes frequently as recently as October 2020.

Tibetans in the area hold the firm religious belief that construction of religious structures will help avert natural calamities like the deadly one in 1973. It is along these public religious sentiments that the local Tibetans raised funds for several years to construct the enormous Buddha statues in the area.

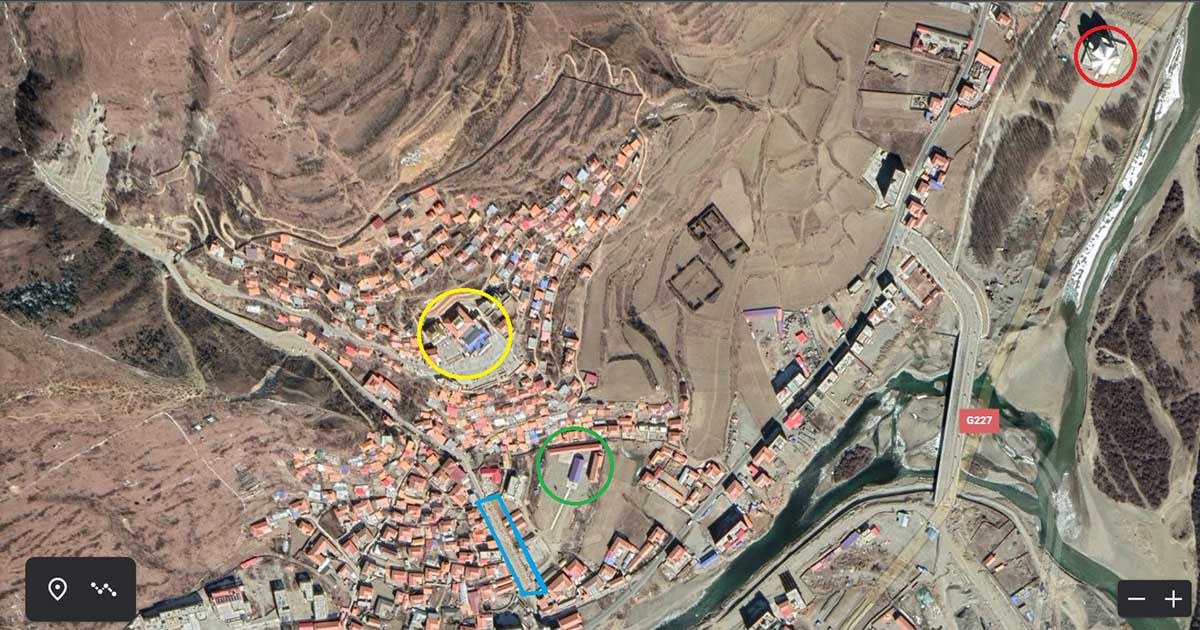

Yellow circle: Matreya statue inside Draggo Monastery

Red circle: large Buddha statue under the canopy

Green circle: Monastic school

Blue rectangle: Mani prayer wheels

(Source: Google Earth)

Red circle: Guru Padmasambhava statue at Chanang Monastery before demolition. Google Earth imagery dated September 28, 2021.

The demolitions: arbitrary and reminiscent of Larung Gar

The demolished Buddha statues in Draggo County were constructed in 2015 after approval from the authorities in accordance with the then-regulations—the 2005 Regulations on Religious Affairs (RRA) and the 2006 Sichuan Regulations on Religious Affairs (SRRA)—and approval documents were issued for the construction. The fact that the statues were allowed to be build and stood for 6 years until its demolition underscore that this approval had been respected also in practice by the relevant authorities.

According to reports by Radio Free Asia, local authorities, in 2021, argued that there had been no fire escape in the temple housing the three-story high statue of Maitreya Buddha, and that the 99-foot Buddha statue had been built too high, and as a result, previous permits were revoked.

There is no information available whether the Chinese authorities in Draggo county have observed legal procedures applicable to demolitions of private property, as for example prescribed in the Administrative Compulsion Law, which stipulates hearing from the affected party and which may even oblige authorities to attain court orders for the demolition of structures. Furthermore, the Administrative Reconsideration Law requires conducting hearings whenever there is a revocation of permits. There is also no information available on a challenge in court, as provided by Chinese law, through the local monastery or other affected institutions.

Significant public protest in Draggo by monks and laypersons instead clearly suggests—as is commonplace among Tibetans—that the local community has no confidence in the fairness of the decisions made by Chinese authorities and courts, as it is understood that there is no independent judiciary nor judicial review of government encroachments on individual rights that are nominally guaranteed by the Chinese Constitution.

In the case of the demolitions of statues in Draggo county, it is highly likely that the authorities have also plainly disregarded procedural law when implementing their measures, and that the local community’s outrage was in reaction to this. Even if there had been grounds for the authorities’ concern for safety, the measures taken appear grossly disproportionate, as more modest means of mitigating any safety issues would have been possible.

In addition, it is critical to note that both the 99-foot Buddha and the 45-foot Guru Padmasambhava statues were built in 2015 prior to the revised national level regulations and the revised Sichuan regulations came into effect on Feb. 1, 2018 and Feb. 1, 2020 respectively. The original RRA and Sichuan RRA were in effect starting March 1, 2005 and November 30, 2006 respectively.

The 2018 revised national level regulations included a new provision that forbids the construction of large, outdoor religious statues outside a monastery, temple, mosque and church. (Article 30). The 2020 revised Sichuan provincial regulations also forbid the construction of large outdoor statues and prohibits projection, lighting or other means to create large outdoor religious images (Article 28).

In comparison, both the original RRA and Sichuan RRA were straightforward and relatively flexible in terms of construction of large outdoor religious statues. The 2005 RRA stipulates that “religious bodies, monasteries, temples, mosques and churches may build large-size outdoor religious statues” on the terms of the religious affairs department of the provincial government agreeing to the construction application and the religious affairs department of the State Council’s examination and decision of approval or disapproval thereof (Article 24). The 2006 Sichuan RRA also provides for building of large scale open-air religious statues and simply refers to relevant provisions of the State Council’s RRA in handling the establishment and registration of places for religious activities (Article 10). This was applicable regardless of the structures being erected on or outside monastic premises.

The revised 2018 RRA and 2020 Sichuan RRA forbid construction of large outdoor religious statues outside religious sites. However, a retroactive application of these regulations through revoking earlier permits appears arbitrary and would effectively leave all outdoor religious structures in Tibet, outside of monastic premises, unprotected. This would constitute a serious intervention into the freedom of religious practice of Tibetan Buddhists, and, with regard to the cultural value of the concerned structures, a threat to Tibetan cultural heritage.

The rigorous demolition of the religious statues is indicative of an even more repressive approach toward the religious community in the county, which is fueled by the new Party Secretary in Draggo county and by dissatisfaction with the work of the authorities in the area. The policies are expressly guided by rhetoric of “law-based governance,” which paradoxically would render legitimacy to local authorities to act arbitrarily and disregard the rights of local communities.

The line of reasoning apparently offered by the local authorities is reminiscent of the large-scale demolitions undertaken at the Buddhist encampment of Larung Gar in 2016, when the authorities cited “correction and rectification obligations” As in the case of Larung Gar, the authorities in Draggo apparently use concerns about infrastructure and safety as a pretext to exert total control over religious practice in the community.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Regulatory framework of China on large outdoor statues »