Analysis of Tibetan representation in PRC leadership in 2024

It is the season of China’s annual meetings in Beijing of its National People’s Congress (parliament) and Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (political advisory body). Popularly called the “Two Sessions,” China has also been using these sessions to tout how well Tibetans and others who are dubbed “ethnic minorities” are enjoying their rights.

This claim was most recently reiterated in December 2023 by a Chinese diplomat who claimed, “The 56 ethnic groups in China are all equal regardless of their size, and are entitled to participate in the governance of state affairs.”[1] In August 2021, Wang Yang, then-chairman of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), during his visit to the Tibetan capital Lhasa to participate in a “Meeting Celebrating the 70th Anniversary of the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet,” claimed that following the “liberation” of Tibet (meaning China’s conquest of the country), “Several million serfs rose and held their future in their own hands.”[2]

It is China’s contention that the Tibetan people have become “masters of their own destiny”[3] since its takeover of Tibet.

This report analyzes the current leadership representation at the national level—and in Tibetan areas at the provincial and sub-provincial levels—and finds that Tibetans have mainly token positions while real power in Tibet continues to be in the hands of non-Tibetans.

The International Campaign for Tibet commented: “The fact that the Communist Party excludes Tibetans from real leadership positions in Tibet gives reason to believe that the party leadership does not trust Tibetans to support CCP rule if they had the choice and, to the contrary, that Tibetans would choose to abolish CCP rule, if they could.”

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the military and the government are considered the three wings of the Chinese governance system, with the government and military being subordinate to the party. Within the party, the three important organs are its Central Committee, the Politburo and the Politburo Standing Committee, with the standing committee being the most powerful. The level at which Tibetans are represented in all these different organs at the national, provincial and prefectural levels of administration indicates the discriminatory nature of China’s governance when it comes to Tibetans.

In 1978, Tibetan scholar Dawa Norbu, who had experienced life in Tibet under Chinese rule before going into exile, wrote how the Tibetan people perceived the Chinese occupation. He said, “The Chinese mission in Tibet was to usher in a new era of progress, with connotations of new miracles to a preindustrial people. As soon as the people of Tibet were able to rule by themselves, the Chinese comrades would return home—or so was defined for Tibetans the alien concept called autonomy.”[4]

Looking at the situation of Tibetans in Tibet in 2024, rather than having their future in their own hands, they continue to be second-class citizens in their own homeland. In 2020, we analyzed the Tibetan representation then under Chinese rule and concluded that while numerically Tibetans had some level of representation, in practice, power was deeply tilted toward non-Tibetans, predominantly Chinese.[5] This situation remains the same in terms of Tibetan representation at the prefectural and county levels four years later.

Under the People’s Republic of China, Tibet is bifurcated into 17 prefectural- and two county-level (under non-Tibetan prefectures) administrative divisions[6]: the Tibet Autonomous Region (with seven prefectural level areas under it); two prefectural-level and one county area under Sichuan province, six prefectural-level areas under Qinghai province, one prefectural and one county level area under Gansu province, and one prefectural-level area in Yunnan Province.

Tibetans in the national-level leadership

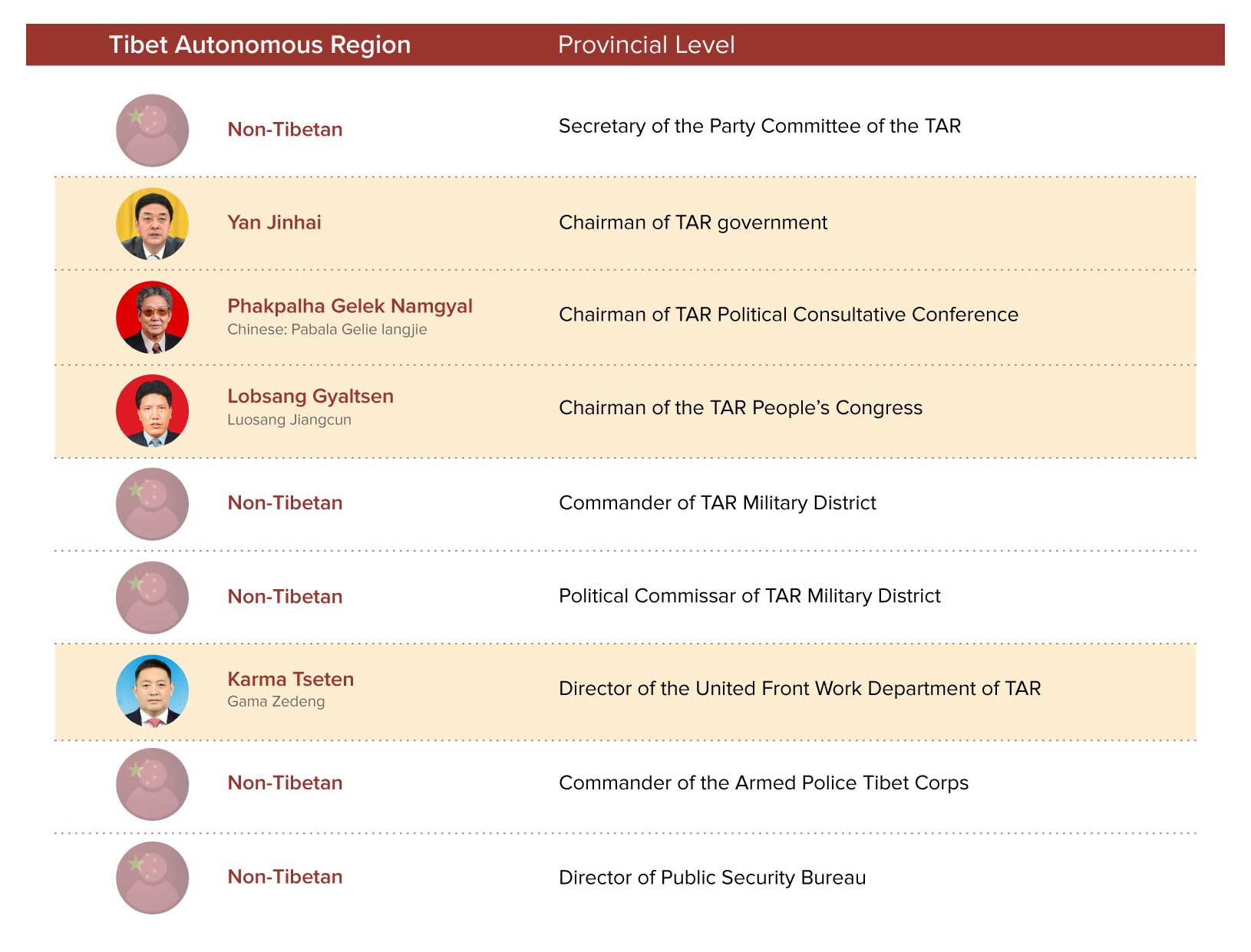

The current 20th Party Congress, whose term is October 2022 to 2027, has only one Tibetan with a seat in the 205 member-strong Party Central Committee.[7] This is one fewer Tibetan than in the 19th Party Congress.[8] Tibet Autonomous Region Chairman Yan Jinhai (born 1962) is the only Tibetan in the current Party Central Committee. No Tibetan has ever found a spot on the Politburo or its real power-wielding Standing Committee.

Yan Jinhai, member of the Party Central Committee and also governor of the Tibet Autonomous Region.

Three other Tibetans are in the 171 alternate members of the 20th Party Central Committee (an increase of one Tibetan from the 19th Party Congress when only two Tibetans were alternates). The Tibetan alternate members are: Karma Tseten (Chinese: Gama Cedain, born 1967), currently member of the Standing Committee of the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) Party Committee and vice chairman of the Tibet Autonomous Region CPPCC; Phurbu Dhondup (Pubu Dunzhu, born 1972), currently a standing committee member of the Sichuan Communist Party of China CPC; and Tsering Thar (Ceringtar, born 1969), currently a member of the Standing Committee of the Qinghai Provincial CPC.

Alternate members of the 20th Party Central Committee Karma Tseten, Phurbu Dhondup, and Tsering Thar.

In the current 14th National People’s Congress, which is China’s parliament (term began in March 2023), one Tibetan, Lobsang Gyaltsen (Luosang Jiangcun, born 1957) is among the 14 vice chairs. Gyaltsen, who currently heads the TAR People’s Congress too, replaced Pema Thinley (Baima Chillin) in the position. In the 159-member NPC Standing Committee, there is only one Tibetan, Jamyang Shepa, who is from Labrang Tashikyil Monastery in Kanlho (Gannan). He has a range of religious and political positions. At the NPC he is also a member of its Ethnic Affairs Committee. Nationally, he also has the position of vice president of the Buddhist Association of China and dean of Tibetan Buddhism College of China. At the provincial level, he is a deputy director of the Standing Committee of the 14th Gansu Provincial People’s Congress, president of the Buddhist Association of Gansu Province and president of Gansu Buddhist Academy.

PC Vice Chair Lobsang Gyaltsen who is also Chair of the TAR PC, and standing committee member Jamyang Shepa.

In the current 14th Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, the highest advisory body in China, only one Tibetan finds a place at the vice president level, the long-lasting Phakpalha Gelek Namgyal (Pabala Gelie Langjie, born in 1940). He was re-appointed one of the 23 vice chairs of the CPPCC in March 2023. Phakpalha has been on and off in this position since the 1970s.

CPPCC Vice President Phakpalha Gelek Namgyal

Five other Tibetans are on the CPPCC Standing Committee, which has a total of 299 members. They are Tashi Dawa (Zhaxi Dawa, born 1959) from Bathang in Kardze (Ganzi) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Sichuan, a writer; Dorjee Rapten (Douji Redan, born 1956), deputy director of the Ethnic and Religious Affairs Committee of the CPPCC; Che Dralha (Qi Zhala, born 1958), currently a deputy director of the CPPCC’s Agriculture and Rural Committee; Drupkhang Thubten Khedrup (rendered in Chinese reports as Trukang Thupden Kheldo or Zhukang Tubdankezhub, born 1955), vice chairman of the CPPCC Tibet Autonomous Region; and the China-selected Panchen Lama. This is the highest position that has been assigned to Gyaltsen Norbu (born 1990), whom the CCP selected in November 1995 to be its Panchen Lama after disappearing Gedhun Choekyi Nyima, the Panchen Lama recognized by the Dalai Lama.

From left, Che Dralha, Dorjee Rapten, Tashi Dawa, Drupkhang Thubten Khedrup, and CCP-selected Panchen Lama

Although not on the CPPCC Standing Committee, Penpa Tashi (Bianba Zhaxi, born 1964) is a deputy director of the CPPCC Ethnic and Religious Affairs Committee. He also has a government position (see below).

In the government under current Premier Li Qiang, no Tibetan finds a place in the minister level or higher. Dorje Tsering (Duoji Cairang) from Kanlho (Gannan) is the only Tibetan to have served at the level of a minister in Beijing. He served two terms as Minister of Civil Affairs from March 1993 to March 2003, thereafter being made chairperson of the 10th NPC Ethnic Affairs Committee. Currently, Penpa Tashi (born 1964) is a member and deputy director of the National Ethnic Affairs Commission.

No Tibetan finds a place in the NPC committee. In the CPPCC, there are four Tibetan deputy directors: Che Dralha in the Agriculture and Rural Areas Committee, Penpa Tashi and Dorjee Rapten in the Ethnic and Religious Affairs Committee, and Cui Yuying in the Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan Overseas Chinese Liaison Committee.

China’s crisis of Tibetan leadership at the national level

In the post-1959 period, the Chinese authorities have tried to groom a Tibetan official within its system who could command the respect of all the Tibetan people and who could be expected to serve as the CCP’s mouthpiece. Through this they hoped they could divert the Tibetan people’s loyalty and devotion to the Dalai Lama to someone else of their choosing.

Initially, they sought to see if the previous 10th Panchen Lama could be the one, but he essentially expressed his devotion to the Dalai Lama and stood firm as an outspoken critic of Chinese policies on Tibetans. Even as he worked within the Chinese system, the 10th Panchen Lama was able to use his office to work for the welfare of the Tibetan people by challenging officials on policy matters.

None of the other Tibetan officials at the national level, including Ngapo Ngawang Jigme, Bapa Phuntsok Wangyal and Ragdi, have come anywhere close to the respect enjoyed by the previous Panchen Lama, let alone by the Dalai Lama. Phakpalha Gelek Namgyal, a prominent lama from the Geluk tradition and the longest-serving Tibetan official under the Chinese system, also lacks pan-Tibetan legitimacy. Since the time of Ragdi, hardly any of the successive Tibetans put in positions in Beijing, including current ones like the two traditionally high Tulkus (reincarnations) Jamyang Shepa and Phakpalha, have been seen to be active and publicly taking up issues relating to the Tibetan people, the way the previous Panchen Lama did.

Tibetans in the United Front Work Department

The Communist Party organ the United Front Work Department (UFWD) plays a pivotal role in the Chinese government’s policies on Tibet. In 2018, significant structural reforms were announced that placed the UFWD in charge of policy areas like religious affairs and “ethnic minorities.” Drawing attention to this strengthened role for the United Front, Xi Jinping gave major guidelines during the Central United Front Work Conference in July 2022. In January this year, Chinese state media interestingly republished parts of a speech that Xi Jinping gave then in 2022 wherein he emphasized that they should focus on “forging a strong sense of community for the Chinese nation” and that the “principle that religions in China must be Chinese in orientation should be upheld.”[9]

This will have an impact on life in Tibet. Although the UFWD always played an important role in Tibet policy in the past, including the establishment of its seventh bureau in 2005 specifically to deal with Tibetan affairs, Xi’s focus leading to the structural change gave it even more power and significance in overseeing the implementation of the policies in Tibet and in particular in altering Tibetan identity, including through controlling the monastic community.

However, since its establishment in 1948, to date the only Tibetan to be in a senior UFWD leadership position is Sithar (Sita), who was a vice minister in the Central United Front from 2006 to 2016. Sithar has since retired from the United Front but appears to still be involved in Tibet-related work.

One reason for this crisis of Tibetan leadership at the national level is the Chinese leadership’s lack of trust and confidence in the Tibetan people, even those who hold comparatively senior positions. Any Tibetan leader who expresses views concerning legitimate grievances of the Tibetan people becomes liable for persecution after being accused directly or indirectly of “local nationalism.” The life of the 10th Panchen Lama and Bapa Phuntsok Wangyal are cases in point. Even though they worked within the Chinese system and were looked upon as being pro-Chinese by a section of the Tibetan people, they suffered many years of imprisonment and torture because the authorities did not trust them and persistently believed that they had a hidden agenda.

Non-Tibetans continue to be the majority in the provincial and prefectural leadership

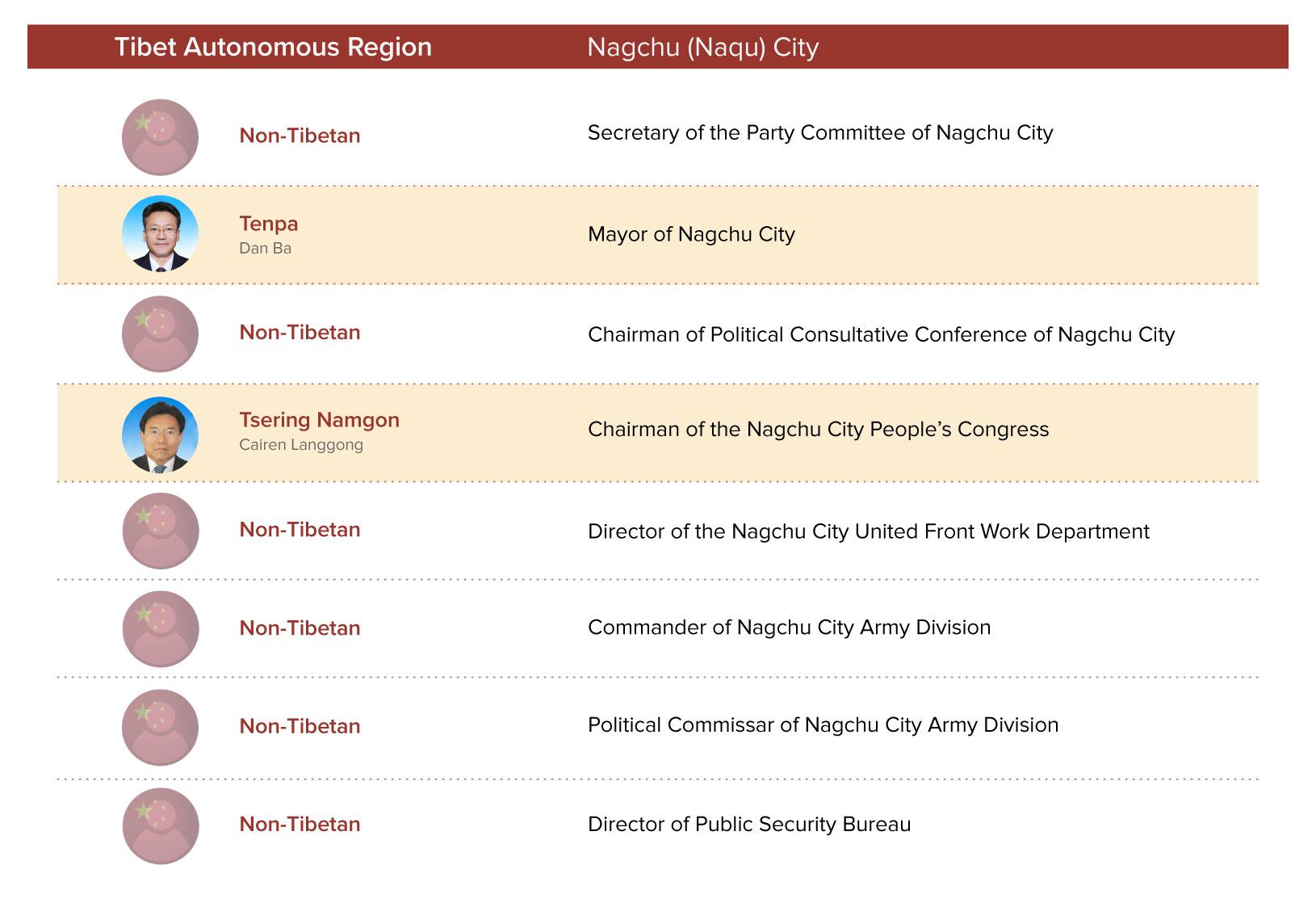

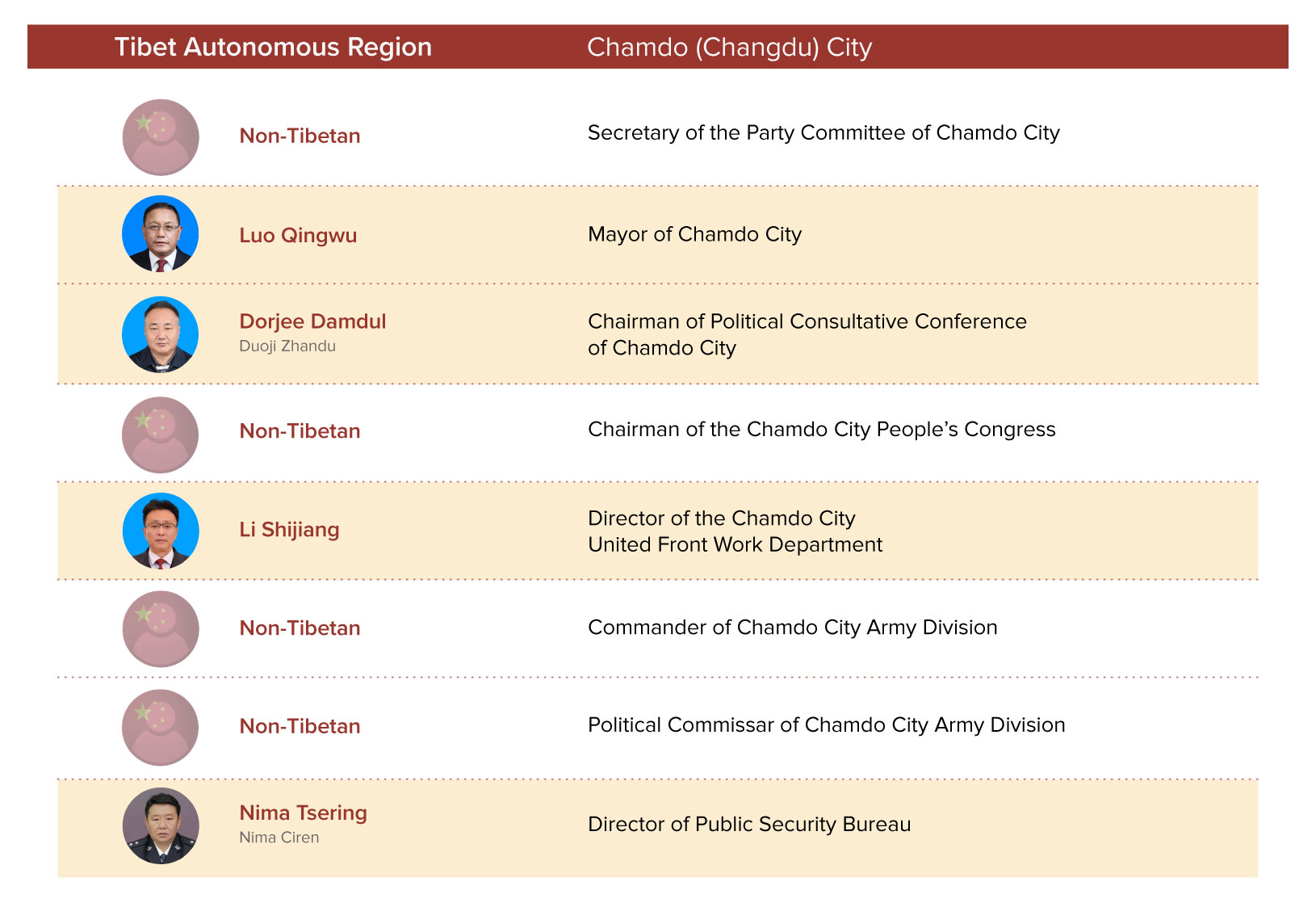

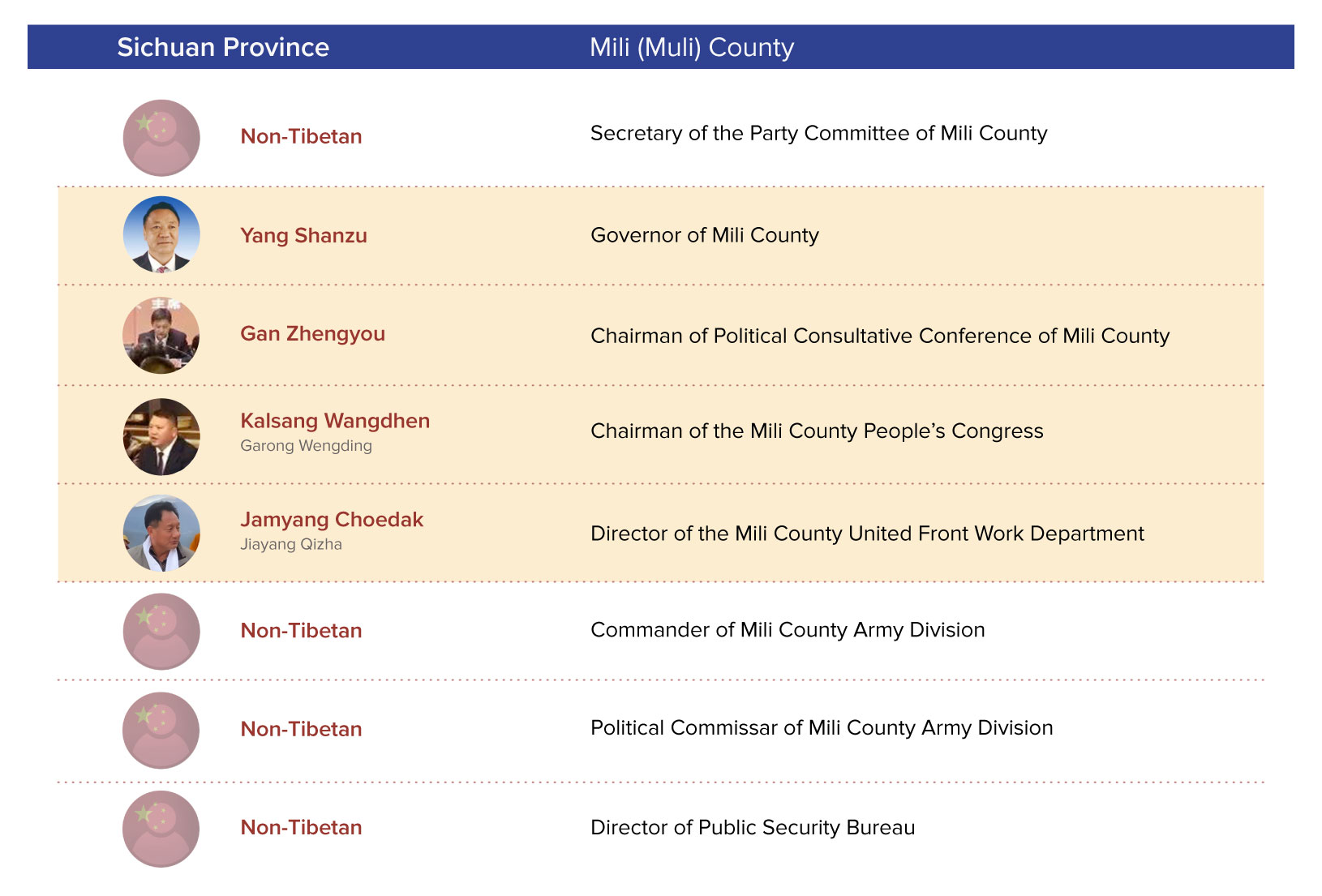

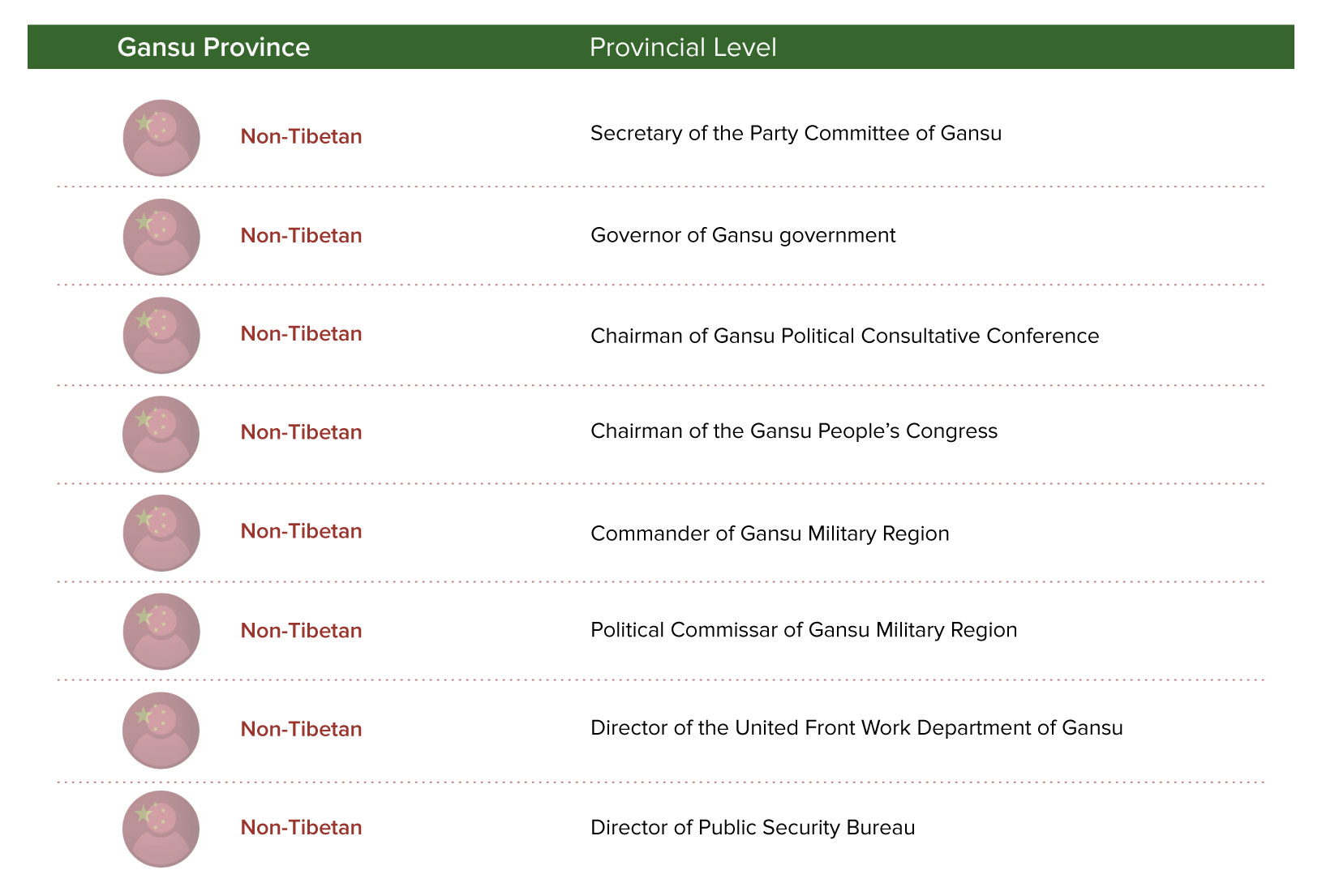

Non-Tibetans continue to hold the majority of party leadership positions at the provincial and prefectural level of administration.

Representation in the Communist Party

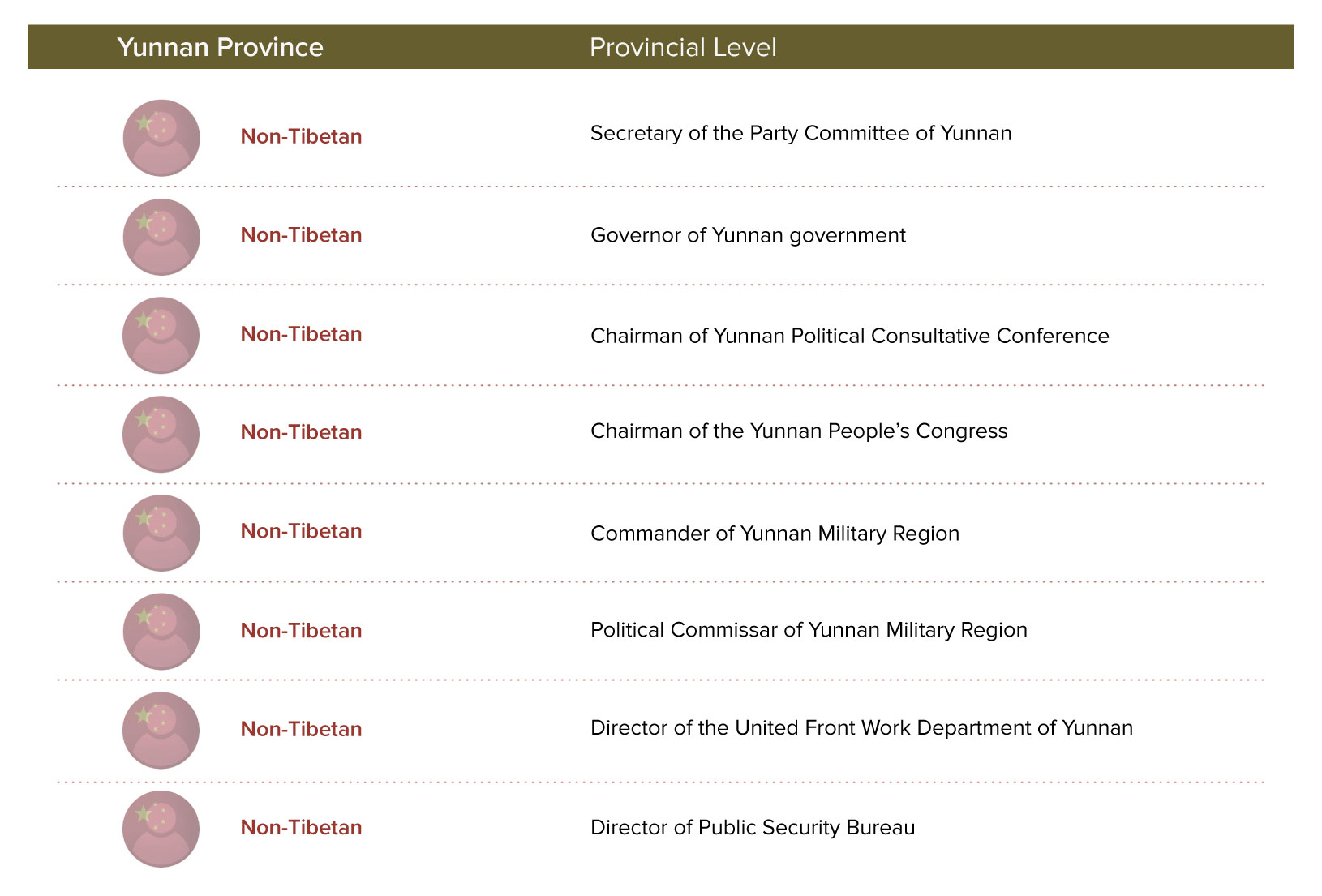

At the provincial level, the party secretary of the Tibet Autonomous Region continues to be a non-Tibetan, as those of Qinghai, Yunnan, Sichuan and Gansu provinces are too.

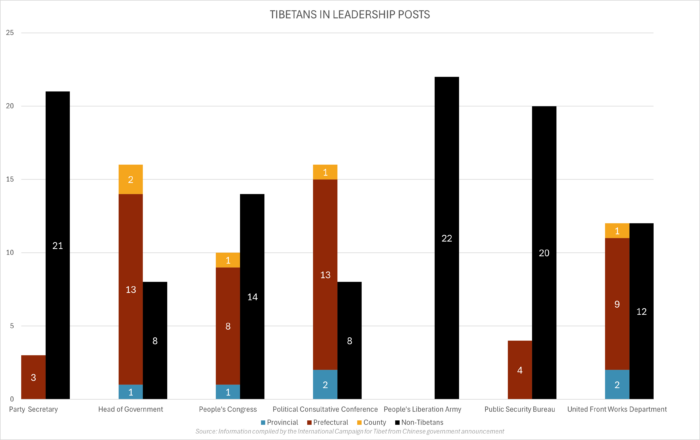

At the prefectural level, some Tibetans find a place as party secretary, but the number has decreased since our last report on the leadership in 2020. Of the 17 Tibetan prefectural-level and two county-level administrations, only three—Lhasa and Shigatse in the TAR and Tsojang (Haibei) in Qinghai—have Tibetans as party secretaries. This is one fewer than in 2020 when the party secretary of Tsolho (Chinese: Hainan) Prefecture in Qinghai was a Tibetan.

Representation in the government

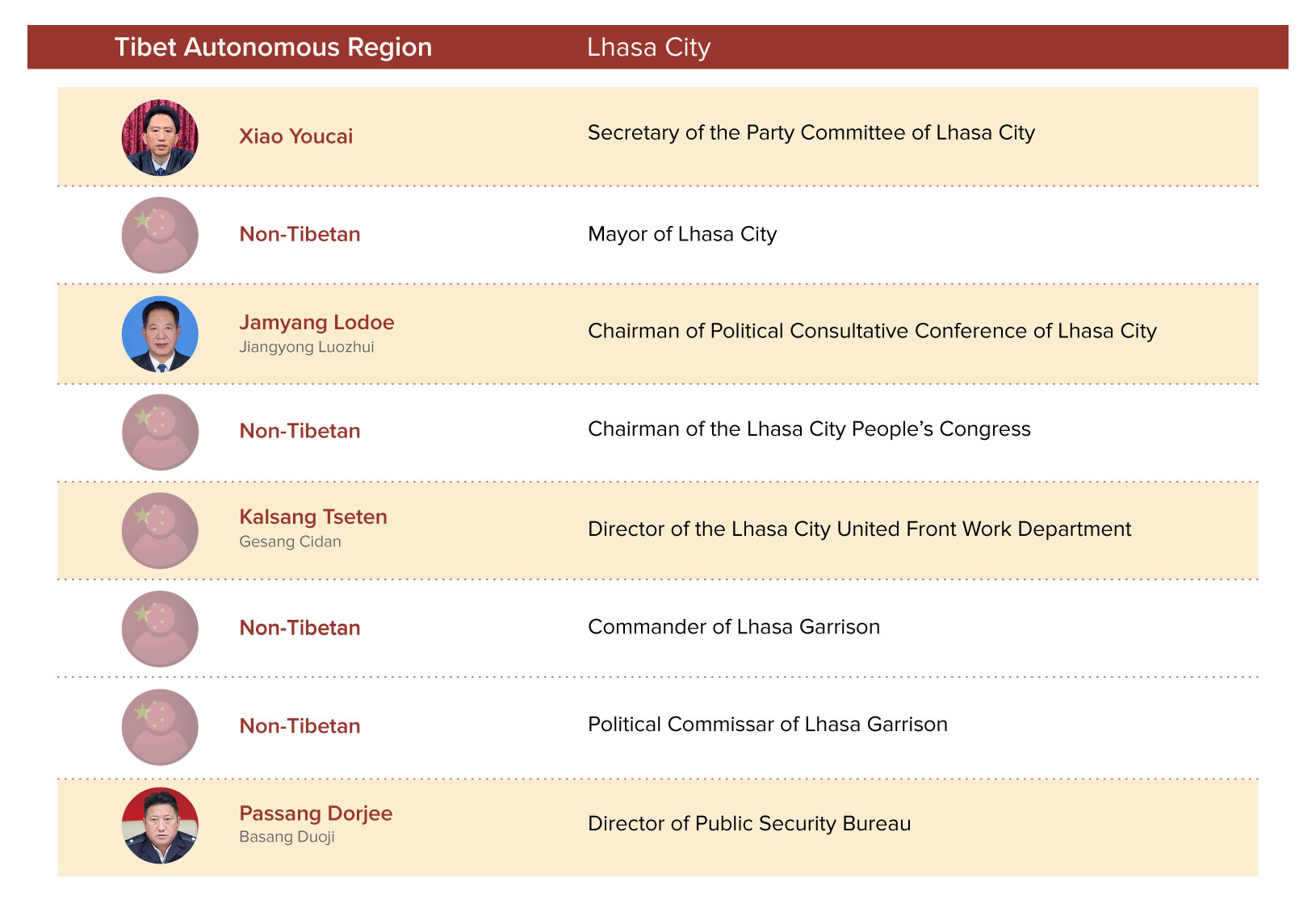

Tibetan representation at the head of prefectural-level governments also decreased from 14 in 2020 to 13 in 2024; Wang Qiang (Chinese) replaced Gho Khog (Tibetan) as the mayor of Lhasa in December 2022.

Representation in the People’s Congress and consultative conference

In the People’s Congress, there are eight Tibetans in 2024, three fewer at the prefectural level than in 2020. Only in the Political Consultative Conference is there an increase from 2020 numbers.

China’s securitization imperatives mean no Tibetans in security-related leadership

In his speech to the NPC on March 13, 2023, President Xi Jinping reiterated his focus on security, saying, “Security is the foundation of development and stability is the prerequisite for prosperity. We must resolutely pursue a holistic approach to national security, improve the national security system, strengthen our capacity for safeguarding national security, enhance public security governance, and improve the social governance system.”

China analyst Susan Shirk observes that, “Under Xi, the CCP’s stability-maintenance machine has become more efficient and more totalitarian.”[10] Similarly, the German think tank Mercator Institute for China Studies says in a report about Xi Jinping’s national security approach, “The CCP leadership is particularly wary of sources of shared identity outside the nation and the party, which might give rise to collective action. In recent years, the party state has initiated repeated crackdowns against groups bound by ethnicity, language, religion, or common causes, especially those with multiple such ‘indicators’ of potential threats.”[11] Accordingly, China’s securitization strategy in Tibet had stability maintenance as a paramount objective. Therefore, the role of the security-related offices assumed importance, whether it was the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), the People’s Armed Police (PAP) or the Public Security Bureau (PSB).

Representation in the security agencies

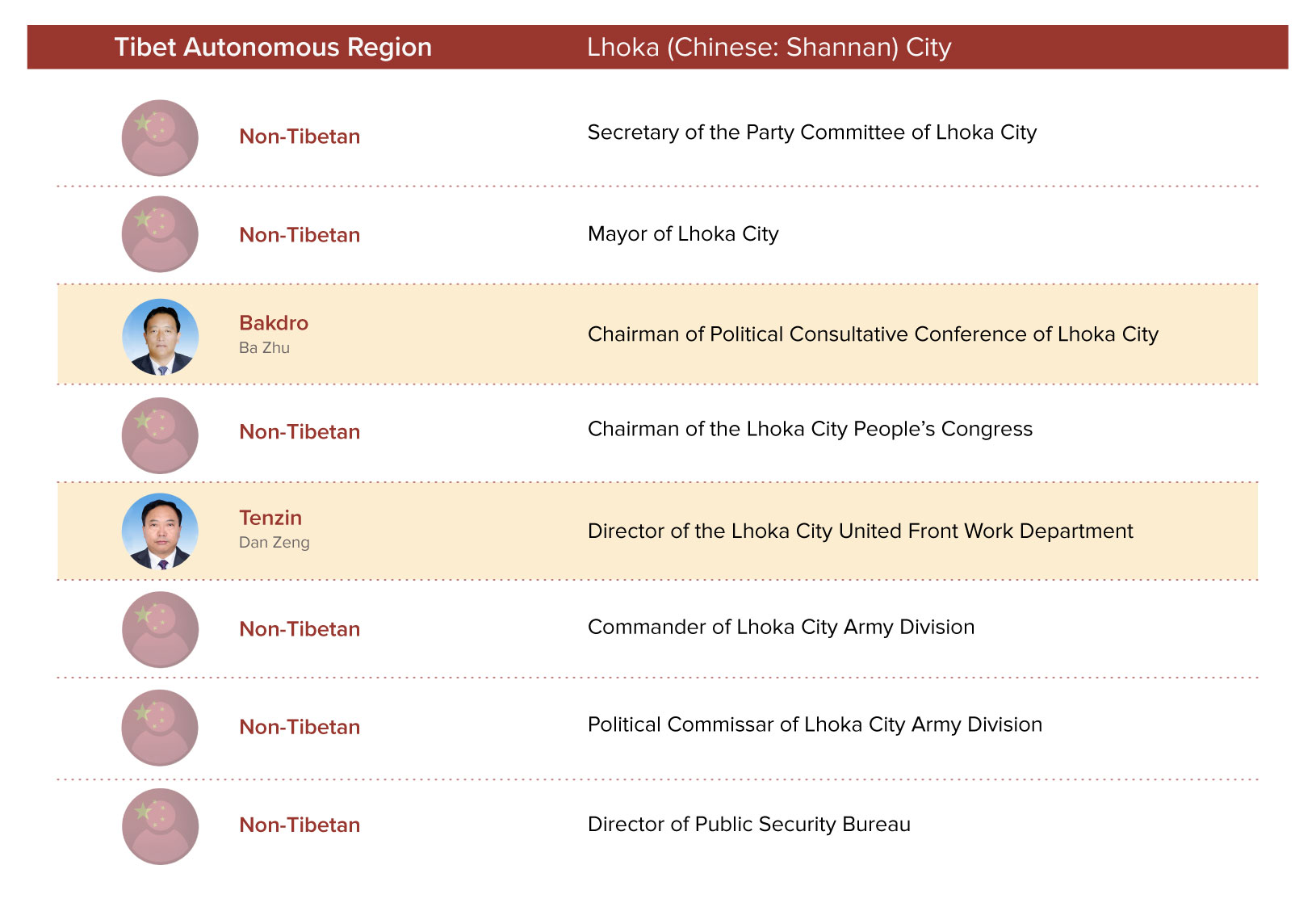

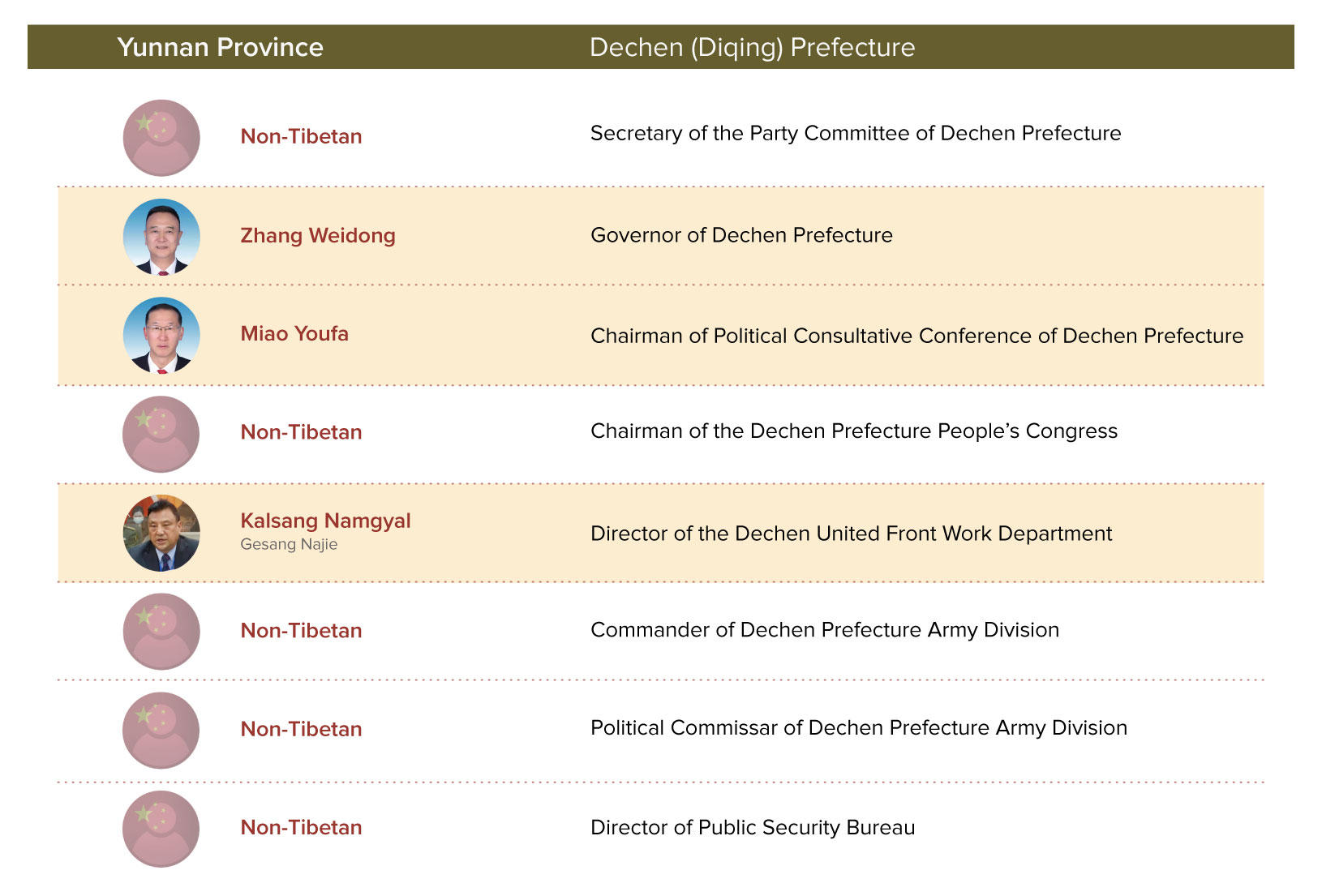

If we look at the leadership of the security entities in Tibetan areas, we can see that almost all are non-Tibetans, both at the provincial as well as the prefectural levels. As can be expected, almost all heads of the PLA leadership at all levels in Tibet are non-Tibetans.

The PSB in particular has been at the forefront of China’s control and suppression of the Tibetan people. The PSB is the one that surveils Tibetans on a day-to-day basis. For example, ahead of the Dalai Lama’s birthday on July 6, 2022, the Lhasa Municipality Public Security Bureau was the one that offered rewards for Tibetans reporting on crimes against “state security” in order to “build an iron wall of stability.” Similarly, it was the Yulshul (Yushu) City Public Security Bureau that interrogated and tortured Tibetan language rights activist Tashi Wangchuk in October 2023.

PSB personnel are stationed even within the monastic compounds. PSB forces were the ones that entered the Larung Gar Buddhist Institute near the town of Serthar (Chinese: Seda) in eastern Tibet (present-day Sichuan Province) on Dec. 25, 2002, to demolish the huts there.

In addition to its involvement in restricting religious activities, the PSB also seems to be the one that is responsible for the racially discriminatory denial of passports to Tibetans even though all citizens of the People’s Republic of China are entitled to one.

If we look at the PSB in Tibet, no Tibetan heads it at the provincial level. Only four prefectural-level heads out of 17 are Tibetans. This could be interpreted to imply that the CCP does not trust Tibetans enough to be leading these offices.

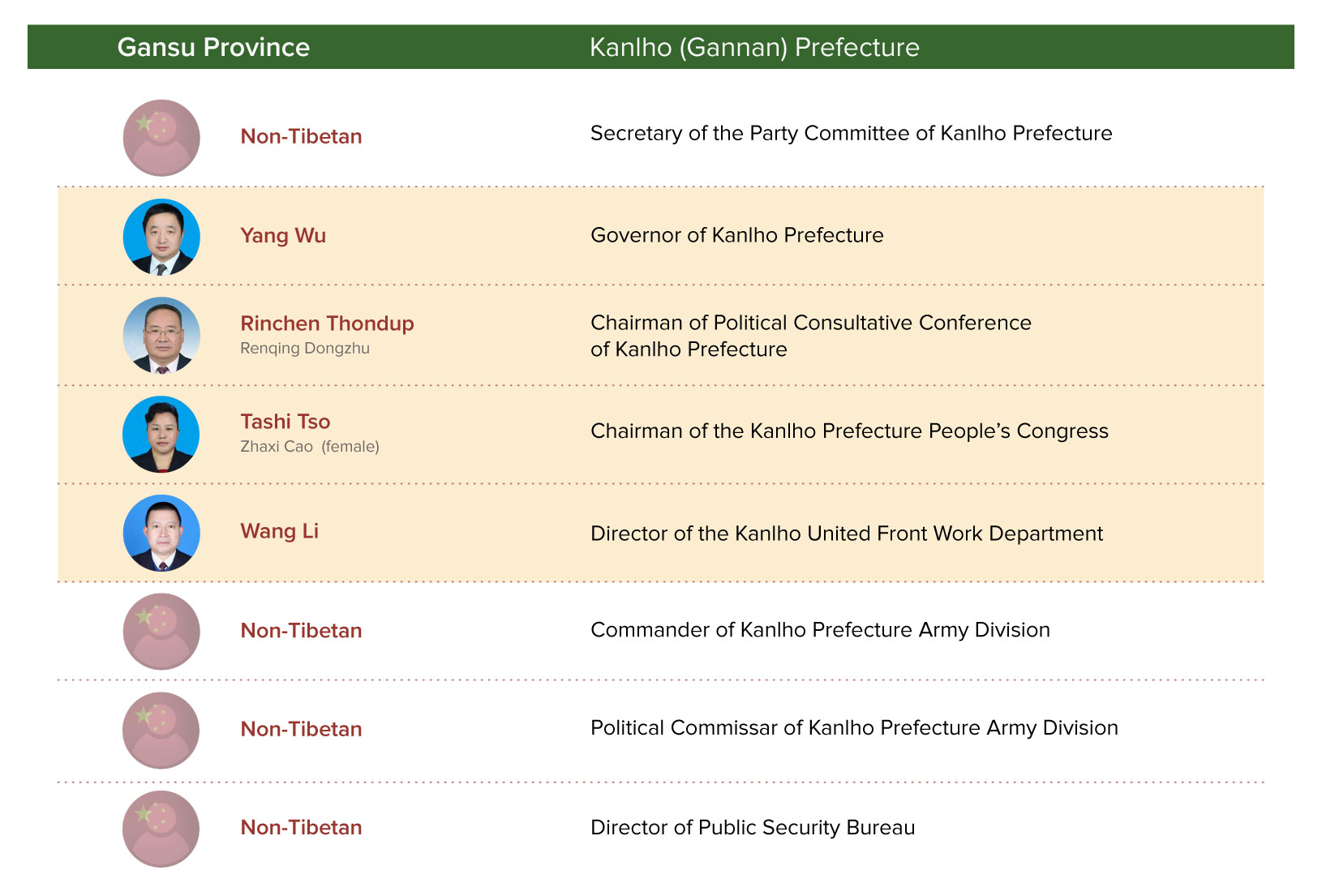

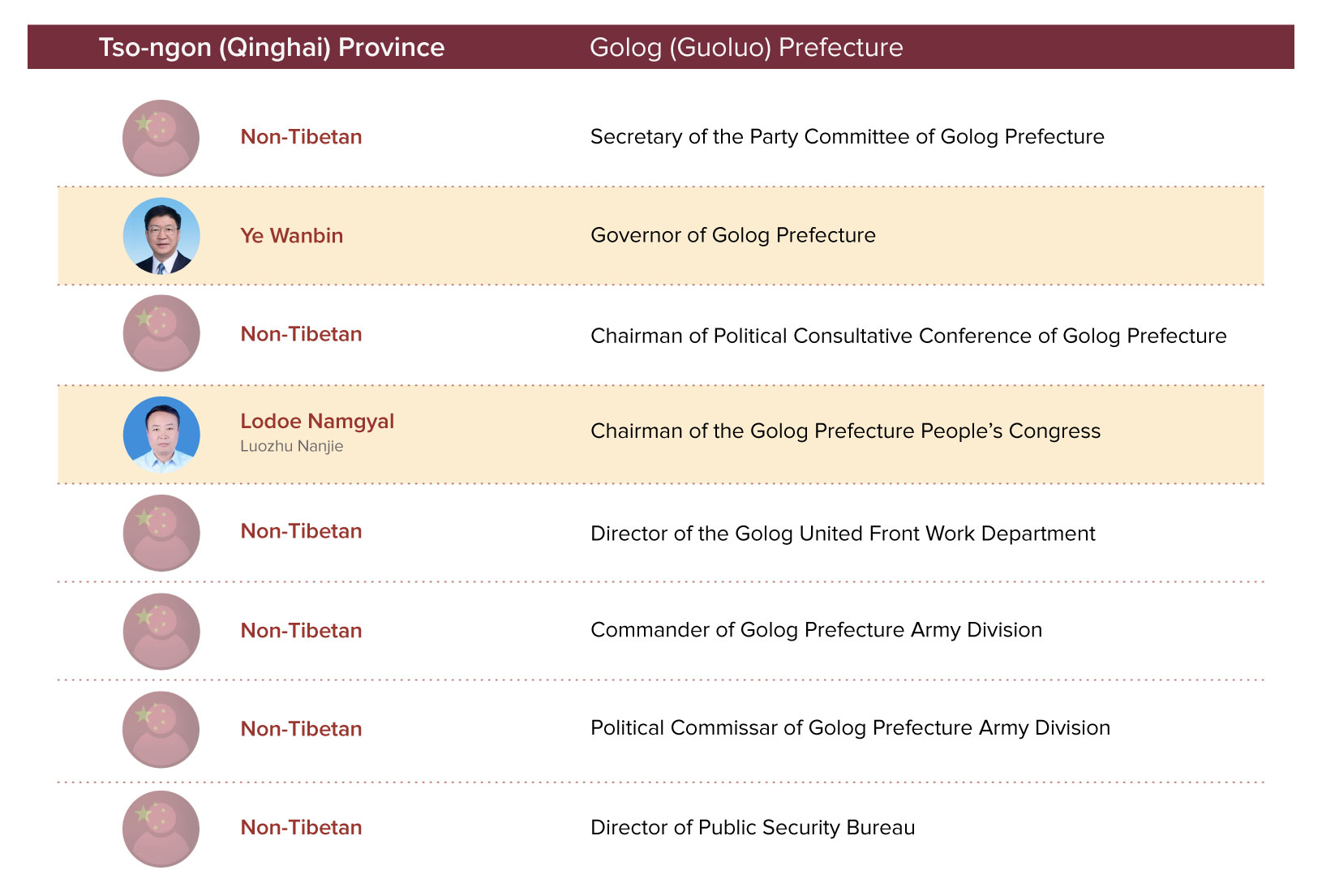

Lists of leaders

Below are lists of leadership positions at the provincial and sub-provincial levels in Tibetan areas.

Footnotes:

[1] Explained: China’s ethnic policy and governance, CGTN, Dec 15, 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20240207155628/https://newseu.cgtn.com/news/2023-12-15/Explained-China-s-ethnic-policy-and-governance-1pxbpZndvYk/index.html

[2] Wang Yang at “meeting celebrating 70th anniversary of peaceful liberation of Tibet”, Xinhua, August 20, 2021, http://en.cppcc.gov.cn/2021-08/20/c_653372.htm

[3] See for example, this White Paper, “Tibet’s Path of Development Is Driven by an Irresistible Historical Tide,” The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, Beijing, April 2015

[4] When the Chinese Came to Tibet, Dawa Norbu, September 1, 1978, https://www.carnegiecouncil.org/media/series/100-for-100/when-the-chinese-came-to-tibet

[5] Position without Power – Tibetan Representation in the Chinese Administrative System, International Campaign for Tibet, October 15, 2020, https://savetibet.org/position-without-power-tibetan-representation-in-the-chinese-administrative-system/

[6] China has divided the Tibetan areas into the following administrative areas. The Tibet Autonomous Region with six prefecture-level cities of Lhasa, Shigatse, Nagchu, Lhoka, Chamdo, Nyingtri, and one prefecture, Ngari. In Sichuan, two prefectures, Kardze and Ngaba prefectures, and Mili (Muli) county in Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture; In Gansu, one prefecture, Kanlho, and one county, Pari (Tianzhu); in Yunnan, one prefecture, Dechen; in Qinghai, six prefectures, Tsonub, Tsojang, Tsolho, Malho, Golog and Yulshul. Also in Qinghai, in Tsoshar (Haidong) City, there are four Tibetan townships each in Bayan (Hualong) Hui Autonomous County and in Xunhua Salar Autonomous County, one Tibetan Townships in Ping-an County, two Tibetan townships in Drotsang (Ledu) County, one Tibetan township in Minhe Hui and Tu Autonomous County and two Tibetan townships in Huzhu Tu Autonomous County, and under Xining City, there is one Tibetan township in Huangzhong County, two Tibetan townships in Datong Hui and Tu Autonomous County, and one Tibetan Township in Tongkor (Huangyuan) County

[7] https://savetibet.org/chinas-20th-party-congress-intensification-of-security-and-assimilation/

[8] Xi Jinping cements grip on power at Party Congress: new leaders revealed and their influence on Tibet policy, International Campaign for Tibet, November 1, 2017, https://savetibet.org/xi-jinping-cements-grip-on-power-at-party-congress-new-leaders-revealed-and-their-influence-on-tibet-policy/

[9] “Xi’s article on Party’s united front work to be published”, Xinhua, January 15, 2024, https://web.archive.org/web/20240115130902/https://english.news.cn/20240115/ba783ab50f054552af29d861122cc641/c.html

[10] China in Xi’s “New Era”: The Return to Personalistic Rule, Susan L. Shirk, Journal of Democracy, April 2018, https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/articles/china-in-xis-new-era-the-return-to-personalistic-rule/

[11] CONFIDENT PARANOIA Xi’s “comprehensive national security” framework shapes China’s behavior at home and abroad, Mercator Institute for China Studies, Katja Drinhausen & Helena Legarda, September 15, 2022, https://merics.org/sites/default/files/2023-02/Merics%20China%20Monitor%2075%20National%20Security_final.pdf