INTRODUCTION

In this briefing, the International Campaign for Tibet summarizes some of the People’s Republic of China’s most serious human rights violations in Tibet during the period from 2008 to the present. This is by no means a complete accounting of every abuse China has committed in Tibet over that period, nor is Tibet the only front on which China is committing grave abuses. The Chinese government’s recent record in Hong Kong, East Turkestan (also known as Xinjiang), and against other religious and ethnic minorities, also demands serious condemnation.

When the 2022 Winter Olympics opening ceremony takes place in China next February, almost 14 years will have passed since the 2008 Beijing Olympics. During these interim years, the People’s Republic of China’s authoritarian regime has committed serious and wide-ranging human rights abuses in Tibet. The severity of these abuses requires the International Olympic Committee to review the selection of the PRC as host for the Games. Absent concrete, measurable commitments to reform from the Chinese government, the IOC should revoke its decision to grant the PRC the privilege of hosting the Games. Additionally, governments should institute a diplomatic boycott of the Games and adopt a public position on the urgent need for the PRC to respect human rights in Tibet.

- Peaceful protests put down with lethal force, writers and singers arrested

- Deeper restrictions on Tibetan Buddhism

- Tibetan language and culture threatened by forcible assimilation

- Cutting-edge technology used to crush dissent

- Repression leads to more than 150 Tibetan self-immolations

- Coercive labor and resettlement programs infringe rights of at least 2 million

“In light of China’s constant abuses against the Tibetan people, the IOC must consider whether allowing China to host the games again constitutes an endorsement of this behavior,” ICT Interim President Bhuchung Tsering said. “China’s disgraceful record speaks for itself. Now it is time for the rest of the world to speak up.”

2008 OLYMPICS: PROMISES MADE, BROKEN

During bidding for the 2008 Games, the PRC’s Olympic bid chief Wang Wei promised that “the games coming to China […] also enhances all social conditions, including education, health and human rights.” Wang assured journalists that “we will give the media complete freedom to report when they come to China.”

The PRC’s failure to live up to these promises was recognized broadly as the 2008 Olympics approached, including by ICT, which reported that despite China’s pledges, “human rights violations remain systematic and widespread, and there is a resurgence of hardline policies aimed at Tibetan religious and cultural religious traditions.” One week before the Games began, an Amnesty International report found that, “there has been no progress towards fulfilling these promises, only continued deterioration.”

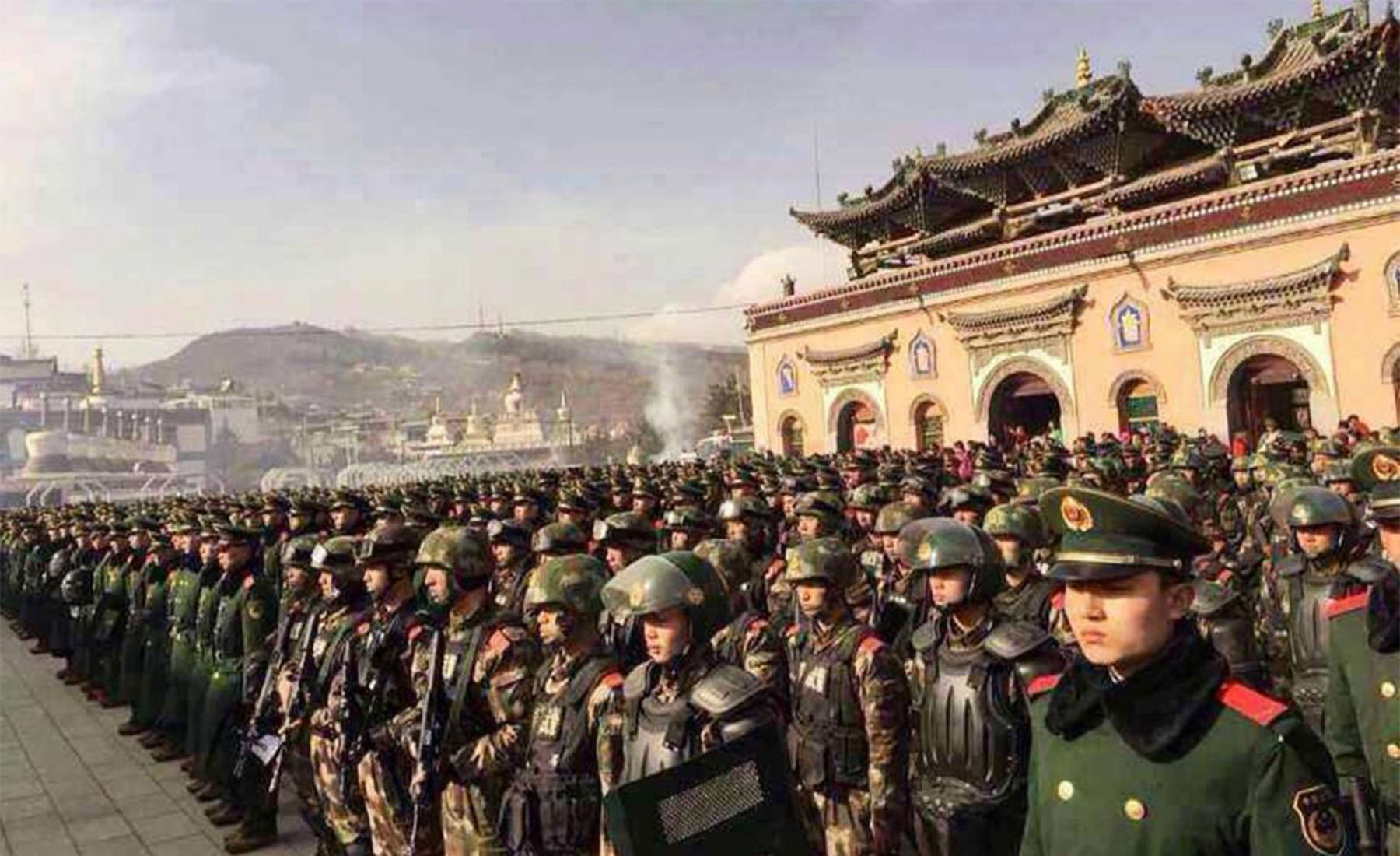

The 2008 Tibetan Uprising, which began in March, provided a clear example of the Chinese regime’s approach to human rights. When Tibetans demonstrated for freedom, human rights and the return of the Dalai Lama to Tibet, Chinese security forces responded to these overwhelmingly peaceful protests with lethal force, brutal crackdowns and a news blackout. The IOC declined to relocate the Games from China despite the bloodshed and broken promises. This decision has taken on even greater weight given the events of the following years and the subsequent awarding of the 2022 Games to China.

In the year after the 2008 Olympic Games, the PRC adopted an increasingly harsh and systematic approach to silencing Tibetans and suppressing dissent. Authorities directed security forces to “crush” any signs of support for the Dalai Lama. ICT was able to document more than 600 Tibetan political prisoners who were detained in this period; the real number of those abducted by Chinese police in response to the protests is certainly much higher, but with journalists locked out of Tibet and a culture of fear and intimidation firmly in place, a more thorough accounting of the Chinese government’s abuses remains impossible.

By 2010, Tibetan writers, singers, and educators were becoming prime targets of the Chinese security state. Dozens of Tibetans who dared to refute the PRC’s heavy-handed propaganda and sought to honestly discuss the events of 2008 were hit with lengthy prison sentences for their words. Gartse Jigme, a monk and writer, stated that, “As a Tibetan, I will never give up the struggle for the rights of my people. As a religious person, I will never criticize the leader of my religion. As a writer, I am committed to the power of truth and actuality. This is the pledge I make to my fellow Tibetans with my own life.” Following his arrest in 2013, Jigme would languish in prison for five years.

Gartse Jigme is celebrated upon his release in 2018.

SELF-IMMOLATIONS: FIRE ON THE GRASSLAND

Amid an ongoing crackdown on religious practice, cultural practices and freedom of expression, in 2009, a young monk named Tapey set fire to himself in protest. More than 150 Tibetans are known to have committed self-immolation protests since then: men and women, young and old, monastics and laypeople. Committed in the face of extreme oppression and in environments where traditional forms of dissent have become impossible, this form of protest has been undertaken for decades—including outside Tibet, perhaps most vividly during the Vietnam War. The Dalai Lama has said that such acts sadden him and urged Tibetans to consider whether there are other ways to better serve their cause. In Tibet, the wave of self-immolations reached its height in 2012 and has continued at a slower pace since, due in part to terrifying regulations that criminalize the family and community of self-immolators.

Some of the more than 150 individuals noted above left behind writings or audio recordings explaining their motivation. In her analysis of these statements, the Tibetan writer Tsering Woeser found that as political statements, the self-immolation protests defied the dehumanizing political environment that China has created in Tibet. “They think we are afraid of their weapons and their repression” wrote one self-immolator named Tenzin Phuntsok, “but they are wrong.” Lama Sobha, a prominent religious figure from the Golog region of Tibet, wrote that through his self-immolation, he intended to “give away my body as an offering of light to chase away the darkness.”

Tibetans carry the body of self-immolator Tamdin Thar, wrapped in prayer scarves, to a site for cremation.

China responded to the outbreak of self-immolations with further repression and violence. Tapey was shot by Chinese police while he burned; arrests and disappearances followed in other cases. In official media outlets, the Chinese government launched a slanderous campaign to blame the Dalai Lama and “outside forces” for the self-immolations, while Chinese courts arranged sham trials to convict friends and family of the self-immolators with “aiding” or “inciting” self-immolation protests. A set of regulations that passed in April 2013 in one of the areas where several self-immolations occurred threatened entire communities with financial and other penalties, in contravention of the prohibition of collective punishment laid out by the Geneva Convention.

POLITICAL PRISONERS: TORTURE AND IMPUNITY

In the wake of the Tibetan Uprising and the 2008 Beijing Olympics, Chinese authorities adopted even harsher methods to suppress dissent. This resulted in a sharp spike in the number of political prisoners, as noted above. Although the PRC officially prohibits torture, it has become endemic in Tibet under the guise of ensuring “stability” through even the most violent means and fostered by a culture of impunity among officials, paramilitary troops and security personnel. It appears to have become common knowledge among Tibetans that they will be subjected to torture when taken into custody, particularly if they’ve taken part in political protest.

In 2015, ICT documented the cases of 29 political prisoners who were tortured, including 14 who died as a result of their wounds. A full accounting of Tibetan political prisoners since 2008 is beyond the scope of a single report; the number of those taken away by the Chinese government in 2008 alone was greater than 1,200, and the total over the last 13 years is likely significantly more.

Goshul Lobsang, a Tibetan political prisoner, was severely tortured in prison and died in his home shortly after being released early in order to avoid his death in custody.

Prominent cases since 2008 include scholar-monks with no record of political activities, wildlife conservationists who fell afoul of Chinese officials, the founder of a literary website, a singer who called for Tibetan unity, a shopkeeper who spoke to the New York Times about his petitions for greater Tibetan language education, a farmer who conducted video interviews with fellow Tibetans asking them about their opinions on the Beijing Olympics and a woman who helped organize a birthday celebration for the Dalai Lama with cake and flowers.

An image from a celebration of the Dalai Lama’s birthday. Participants in the celebration were sentenced to up to 14 years in prison for attending.

Two specific cases that gained worldwide notoriety are that of Tenzin Delek Rinpoche and the 11th Panchen Lama. Tenzin Delek Rinpoche, a revered religious figure from eastern Tibet, had been in prison for more than a decade before his sudden death in 2015; his family members escaped to exile and have called for an investigation into the circumstances of his death in custody. The 11th Panchen Lama, meanwhile, was the world’s youngest political prisoner when his enforced disappearance began at age 6 in 1995. Despite persistent calls for his release from around the world, to date China has refused to even provide evidence that he is still alive. During the period from 2008 to the present, he has therefore transitioned from the world’s youngest political prisoner toward becoming one of its longest-serving political prisoners.

There is another important case to note as it relates to the Olympics. In 2008, just days before the Summer Games began, a bold documentary called “Leaving Fear Behind” secretly screened to foreign journalists in Beijing. To create the film, Dhondup Wangchen, a Tibetan filmmaker, and Golok Jigme, a monk and activist, spent about six months traveling on a perilous journey through the eastern regions of Tibet, interviewing ordinary Tibetans about the inhumanity of Chinese rule, as well as their feelings on the upcoming Games. Although the documentary was successfully smuggled to the outside world, both Wangchen and Jigme were arrested and tortured. They eventually fled Tibet. The IOC ignored calls to intervene in their case.

LANGUAGE RIGHTS: CHINA PUSHES MANDARIN

Few issues have cast a longer shadow over Tibet than the future of the Tibetan language. An increasingly assimilationist China has worked to erase and undermine the language, taking every opportunity to push Tibetans towards using Mandarin instead. For example, research has revealed that Mandarin has already become the medium of instruction in 95% of Tibet’s schools, including at the kindergarten level. Some forms of spoken Tibetan are taught as language classes, like a foreign tongue, while a range of local languages used in some areas aren’t taught at all. Private schools that offered classes in Tibetan have been forced to shut down or commanded to switch instruction to Mandarin.

The Chinese government is keenly aware that language defines and conveys cultural identity, especially in a tradition of oral transmission like the Tibetans’, where memorization and recitation are key features of monastic and scholarly pursuit. In yet another recent staggering display of cultural assault, Chinese officials in northern Tibet ordered monks and nuns to speak to each other in Chinese instead of Tibetan, according to an October 2021 report from Radio Free Asia.

Tibetans have sought to nonviolently resist this attack on the backbone of their civilization. Protest movements swept across Tibet in the years after 2008, despite the incredible danger of defying Chinese authorities. Calls to protect the Tibetan language came from eloquent writers, educated monks and young students alike. As protests against the imposition of Mandarin expanded through northern Tibet in 2010, an anonymous Tibetan blogger wrote that “a script is the lifeblood of a nationality, it a fundamental catalyst for a nationality’s culture, and it records the historical path of a nationality’s development.”

In 2016, a Tibetan named Tashi Wangchuk was detained by the police. He had sought to highlight the importance of language because he could not find a place where his two teenage nieces could continue studying Tibetan after officials forced an informal school run by monks in his area to stop offering language classes for laypeople. His experience offers a case study of how China treats even the most mild-mannered attempts at language advocacy. After being ignored by every level of government, Tashi Wangchuk spoke to The New York Times about his efforts. He was promptly arrested and subjected him to a sham prosecution, as well as torture. Tashi was released in early 2021 after five years in prison. His concern about the denial of Tibetan language rights remains unaddressed.

RELIGIOUS FREEDOM: CCP CONTROLS ON TIBETAN BUDDHISM

Infuriated by the role that Buddhist clergy played in the 2008 Tibetan Uprising, Chinese authorities cracked down on religion in the following months and years. Stringent controls on monks and nuns, intrusive new security measures at monasteries, and restrictions on the very practice of Tibetan Buddhism were instituted. These restrictions were immensely distressing to the Tibetan people; the first self-immolation in Tibet took place in 2009, shortly after Chinese authorities canceled a prayer festival meant to commemorate those killed by Chinese police the previous year.

Popular religious leaders have been imprisoned, such as Khenpo Kartse, whose detention in 2013 sparked peaceful protests and a silent prayer vigil. Despite an international outcry, Khenpo Kartse spent two-and-a-half years in prison. Major Buddhist institutions have been targeted, such as the Larung Gar Buddhist Institute, where Chinese authorities demolished living quarters and forced the expulsion of thousands of monks and nuns. Some of these nuns were later forced to wear military clothing and sing and dance for an audience of Chinese officials; Human Rights Watch concluded that the performance was likely intended to humiliate them.

While monks and nuns are frequent targets of the PRC’s ire, this is only part of the PRC’s agenda to eradicate Tibetan Buddhism through overt suppression and control, as well as the insidious process of “Sinicization,” the forced conversion of a distinct culture into the Chinese model.

The Chinese government’s persistent attempts to slander the Dalai Lama and punish those who express even the merest sign of devotion to him reveal how far the Chinese Communist Party is willing to go in violation of religious freedom. For eight centuries Tibetan Buddhists have propagated teachings through identifying the reincarnations of honored leaders, the most important being His Holiness the Dalai Lama. These reincarnations are found through a time-honored set of processes and procedures and represent one of the most distinctive practices of Tibetan Buddhism.

Today, the PRC regime is attempting to subvert this critical part of Tibetan Buddhism. Through a complex set of “regulations,” monastic communities are required to cede the reincarnation process to the Chinese government. To ensure full control of religious leaders, the CCP now decrees the search for reincarnate lamas must be approved by Beijing itself.

The most crucial of Tibetan reincarnates is the Dalai Lama, and the PRC has made clear it will overrule all religious precedent—and the will of Tibetan Buddhists themselves—to install a puppet leader after he passes away. The Dalai Lama himself has stated that he may be the last in his lineage, or that he may choose to reincarnate outside of China’s borders, but these statements have been met with angry denunciations from China.

China’s attacks on Tibetan Buddhism are pervasive to this day. In August 2021, almost 60 Tibetans in the small town of Dza Wonpo were arrested en masse by Chinese police. Their crime? Possessing photographs of the Dalai Lama.

DIGITAL AUTHORITARIANISM: 21ST CENTURY REPRESSION

One of the most ominous developments in Tibet since the 2008 Olympics is the Communist Party’s application of cutting-edge technology and massive manpower to overwhelm and stifle the Tibetan people. Chen Quanguo, the architect of China’s horrifying system of detention camps for Uyghur and other Muslim minorities in East Turkestan (also known as Xinjiang), worked in Tibet as the Communist Party Secretary of the Tibet Autonomous Region from 2011 to 2016. During his tenure, Chen began developing the system of intense security and forced assimilation that he would later inflict on East Turkestan.

A surveillance camera in Lhasa, decorated to look like a religious instrument.

The stated aim of Chen’s program is “breaking lineage, breaking roots, breaking connections, and breaking origins” of Tibetans and Uyghurs. A “grid management” program that Chen implemented in Tibet focused on targeting individuals regarded as potential problems for the Chinese government. The “Solidify the Foundations, Benefit the Masses” campaign that Chen oversaw brought more than 20,000 Chinese officials and Communist Party cadres to Tibetan villages for intense surveillance and political re-education. More recently, new Chinese directives were passed pressing Tibetans to spy on each other and on foreigners in the name of China’s national security. A network of police stations and constant video surveillance equipped with facial recognition software ensure that those who witness prohibited speech or activities and fail to report them may also fall under suspicion.

“It has gone beyond a simple ‘crackdown’ now, and is much more sophisticated and terrifying,” a source told ICT after speaking to a number of Tibetans from different parts of Tibet. “Security is invisible and everywhere. It is no longer only armed police patrolling the streets; often we don’t know who the police are as they blend into society, and officials are in our homes, asking about every part of our lives.”

Last year, scholar Adrian Zenz published a report documenting a large-scale coercive labor program in the Tibet Autonomous Region that pushed more than half a million rural Tibetans off their land and into military-style training centers in just the first seven months of 2020. After their coerced training, many of the Tibetans were sent to other areas of Tibet and China and pushed into low-wage factory and construction work. In response to Zenz’s findings, more than 60 parliamentarians from 16 countries called for “immediate action to condemn these atrocities and to prevent further human rights abuses.” The parliamentarians noted that the coercive labor program involved “enforced indoctrination, intrusive surveillance, military-style enforcement, and harsh punishments for those who fail to meet labor transfer quotas.” They also said the program is frighteningly similar to coercive labor in East Turkestan.

In one vivid example of the sheer power of China’s surveillance and policing apparatus in Tibet, Tibetans who managed to leave the PRC to attend a major Buddhist teaching led by the Dalai Lama in India were individually contacted by Chinese police and ordered to return to their homes. A few years earlier, returnees from one of the Dalai Lama’s teachings were detained; hundreds of Tibetans, many of them elderly, were held in detention centers. Religious items such as rosaries and prayer beads were confiscated, and a Tibetan from Lhasa who is now in exile said that the detentions imposed “unbearable psychological and financial pressure on families and communities.”

New technology and border security measures have also made it nearly impossible for Tibetans to escape to freedom every year. In 2007, the year before the last Beijing Olympics, over 2,300 Tibetans refugees escaped Tibet. In 2008, that number dropped to 588. Last year, it plummeted all the way to five—a 99.8% decrease in 13 years.

CONCLUSION: TIGHTENING AN INVISIBLE NET

Today, Tibet is tied with Syria as the least-free country in the world, according to the 2021 rankings from the influential watchdog group Freedom House. According to the group’s Freedom in the World 2021 report, Tibet has a total score of 1 out of a possible 100 in the global freedom rankings.

The Chinese government does not appear willing to remedy this situation anytime soon—at least not without greater pressure from the international community—as Chinese officials have refused to negotiate with Tibetan exile leaders since 2010. Instead, they have insisted that the Dalai Lama first agree to a number of unreasonable preconditions before resuming dialogue.

The Chinese Communist Party’s abysmal record in Tibet since the 2008 Olympics is clear. The human rights of the Tibetan people are being subjected to serious and persistent violations, and Chinese authorities have deepened long-running trends while introducing new means of repression and control.

Foreign governments and organizations like the International Olympic Committee must make it clear that this behavior comes with a price. Those who lend even tacit support to a regime that is so fundamentally out of compliance with basic and universal rights that are the birthright of every human being are complicit in that regime’s behavior.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The International Olympic Committee has the clear obligation to verify that China abides by its code of ethics and commitments, as ICT has previously said.

At a minimum, the committee must speak up, publicly and openly, without fear of reprisal, about the rights violations in Tibet, East Turkestan (Xinjiang), Inner Mongolia, Hong Kong and elsewhere.

If the committee is unable or unwilling to secure concrete, meaningful reform by the Chinese government, it should revoke its decision to award the 2022 Games to Beijing. Anything less makes the committee culpable.

The IOC and national Olympic committees must also provide athletes with a safe place at the Games. Athletes must not be misused for political propaganda by the Chinese government. They should be fully informed about the situation in Tibet and the human rights violations in China and have a choice to participate with a “human rights disclaimer.”

ICT also once again joins other civil society groups in calling for governments around the globe to commit to a diplomatic boycott of the Games.